Why Unions Matter in the Garment Industry

Nina Daro is a sociology student at City University of New York-Brooklyn College. During Summer 2019, Nina interned for IndustriALL, the global union federation that supports more than 50 million workers around the globe, fighting for freedom of association and collective bargaining for people across industries. Below she shares her experience with IndustriALL and highlights first-hand just how critical it is for garment workers to unionise.

***

This summer, I shadowed Christina Hajagos-Clausen, Director of the Textile, Garment, Shoe, and Leather Sector of IndustriALL Global Union. While my own work was focused on how to get IndustriALL’s affiliates (member unions) more involved with Fashion Revolution Week, throughout this summer, I was in meetings with people from trade unions, brands, all talking about how IndustriALL can continue to create systemic change within the fashion industry by building union power. I started in London working with Fashion Revolution for two weeks, and my next stop was Mauritius, where almost half of the 45,000 migrant workers are from Bangladesh. Migrant workers are recruited in Bangladesh and arrive without the support to read their contracts and are often held to 8-year contracts as they figure it out on their own.

On my first evening in Mauritius, I met one of the women fighting to change these conditions for migrant workers, Jane. She is an executive at the Confederation des Travailleurs du Secteur Privé (CTSP), the affiliate union to IndustriALL. She’s also a very inspiring person. In 2017, Mauritius proposed a national minimum wage, but it fell far short of a living wage. Jane and other union women went on a 10-day hunger strike in order to push for higher wages, and it worked. The new minimum wage is now at least 8,000 Mauritian Rupees across all sectors. Their strike has become a major part of labour movement history in Mauritius and highlighted the struggles of creating well-functioning industrial relations between the Mauritian government, MEXA (the employers’ association) and unions like the CTSP.

On my last day in Mauritius, I visit a factory supplying ASOS, one of the big global retailers that has signed a Global Framework Agreement with IndustriALL. I witnessed each manufacturing process from start to finish – from the yarn which was imported from Pakistan to the final embroidered t-shirt in a plastic bag with the hang tags attached. The supplier took me through the company’s front rooms that showcase the garments they produce, through the design team’s glass conference room, to the steamy rooms where machines are weaving fabric, dyeing and washing the materials, and then into the noisy open spaces where machines embroidered, painted and printed designs onto textile panels. Further on, the sewing lines were somehow even noisier, with conveyor belts hanging from the ceiling, shifting hanging panels to various sewers applying labels, attaching sleeves, and so on. It’s amazing how much technology and labour goes into every aspect of the garment. It’s something I obviously knew in theory and why I was interested in this area of work, but seeing it was like something out of Willy Wonka. Everything we use in our daily lives requires a complicated and orchestrated dance of people, machines, money, and labour to make it happen.

In Mauritius and later on in Myanmar, Vietnam, and Cambodia, we used words like “comrades” and “brother” and “sister” in addressing each other demonstrating that the fight for workers’ rights has been and will be a long fight requiring close relationships. I think no matter what the language barriers are, whether it’s Vietnamese, Burmese, Thai, Khmer, or Bahasa, we all feel the same. In a meeting between a supplier with factories throughout Southeast Asia and a union with members from the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia, every participant began his or her statements with, “thank you all for attending this meeting. It is the first of many, but I’m glad we started with process.” Many of these meetings feel like that. Even my own supervisor once joked about the monumental tasks, where the goal is to “not just maintain,” but, “to make monumental change in the entire sector.” It may feel slow-moving, but it has to start somewhere in order for it to go anywhere.

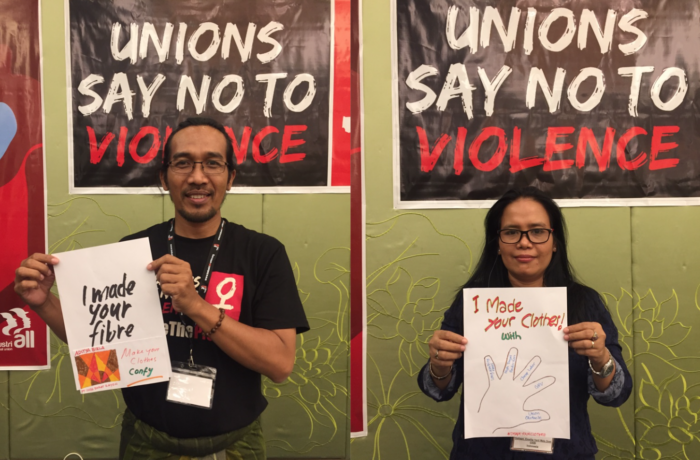

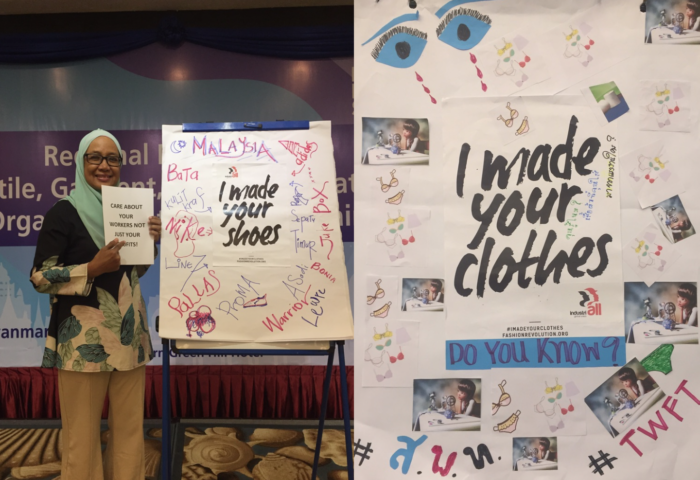

This same sentiment is what brought the I Made Your Clothes campaign alive in a powerful way as we presented to unions about how to get involved in Fashion Revolution Week. Our poster-making session after our presentation gave me goosebumps. Each table of country teams came together to create a picture of the issues meaningful to them. Some members printed out labels and pictures of the garments they produced like Adidas shoes and Next tags. Our effort was to create a massive collage of IndustriALL affiliates holding their own posters, and the participants were connecting to the campaign’s potential. A participant from Malaysia brought me to the corner of the room, where an easel stood facing the wall. She and another comrade had been working on it quietly for over half an hour. All across the large sheet of paper were labels of the brands like Nike, Adidas and Puma. “Malaysia” was written across the top, with an IMYC posters centered on the board. It was amazing to have this reveal in the corner, with the busy scene of chatter, cutting and pasting, and scrawling in the rest of the ballroom-turned-strategic-center. When I helped her carry it onto the stage, she pulled out another piece of paper to pose with. It read, “Care about your workers not just your profits!” and I felt immense pride for the room. These unions from so many different countries were taking ownership of a project that they saw as changing the fashion industry.

Back in New York City, I worked with Workers’ United. I was so excited to invest in the labour movement locally, even though the garment sector in the United States is vastly different from other countries I had visited this summer, especially Southeast Asia. The manufacturing that remains in New York is sample production for brands and niche mom-and-pop shops. However, just before my internship closed, I had the opportunity to go to SEIU’s Pennsylvania Joint Board’s union camp. Towards the end of the week, I was asked to write a small reflection for SEIU’s newsletter. While I was writing, I began to think about a woman I met through Workers United. She introduced me as the “new generation of the labour movement,” but I also thought about Maria, who works three jobs and is looking for a fourth – who also calls this union camp her “vacation.” All around the world, we are all fighting for the same types of things: a living wage, a secure future, respect, a voice. Inspired by Maria, I wrote in the letter:

It’s really amazing to see people stand in front of a room and tell their own story about coming into the labour movement. Some people found out about unions through their own workplace disputes, some people wanted to run for shop steward in order to take on more of a leadership role, and some people see themselves as a part of this worldwide movement in support of workers. Many people see themselves as all of these things. Everyone in the room varies in age, race, religion, country of origin, and language, and yet we are here to work together for something bigger than ourselves. It’s a long fight—but it’s about time and when we fight, we win.