The Wellbeing Wardrobe: In conversation with Dr. Taylor Brydges

As part of our Instagram series exploring the concept of a Wellbeing Wardrobe, we spoke with Dr. Taylor Brydges, one of the authors of the Wellbeing Wardrobe report, commissioned by the European Environmental Bureau, about the key findings from the report.

Fashion Revolution (FR): Let’s get into the first question. What is the wellbeing economy?

Taylor: The wellbeing economy is an alternative to the GDP-driven economic model we’re familiar with. This conventional model has been heavily criticized for its unsustainable environmental impact and its failure to meet basic human needs. Interestingly, research has shown that our consumption-based economies have not necessarily made us happier; there’s often a disconnect between happiness and wellbeing once certain income thresholds are met.

FR: Can you elaborate on how the wellbeing economy shifts the focus in the fashion industry?

Taylor: Certainly. The wellbeing economy shifts the focus to human satisfaction. It encompasses fundamental necessities like food, water, safety, and emotional and social needs, such as meaningful work and community involvement. Transitioning to a wellbeing economy involves moving away from growth-centric economies, aligning with planetary boundaries, reducing inequality, and enhancing overall human wellbeing.

FR: Why do we need a wellbeing economy for fashion?

Taylor: Great question! The need for a wellbeing economy in the fashion industry stems from the fact that many current sustainability efforts can be understood as green growth approaches, which at their core, still prioritise economic gains over meaningful action on environmental and social sustainability.

FR: It’s crucial to address the deeper systemic issues in the fashion industry rather than just focusing on superficial initiatives. Can you provide examples of how this approach can be more meaningful?

Taylor: Certainly. For instance, some brands introduce small “eco-friendly” collections, representing only a fraction of their offerings. This allows unsustainable practices to persist, significantly contributing to global carbon emissions, resource depletion, and biodiversity loss.

FR: It’s about moving beyond token sustainability efforts and implementing comprehensive changes. What would a wellbeing economy for fashion look like?

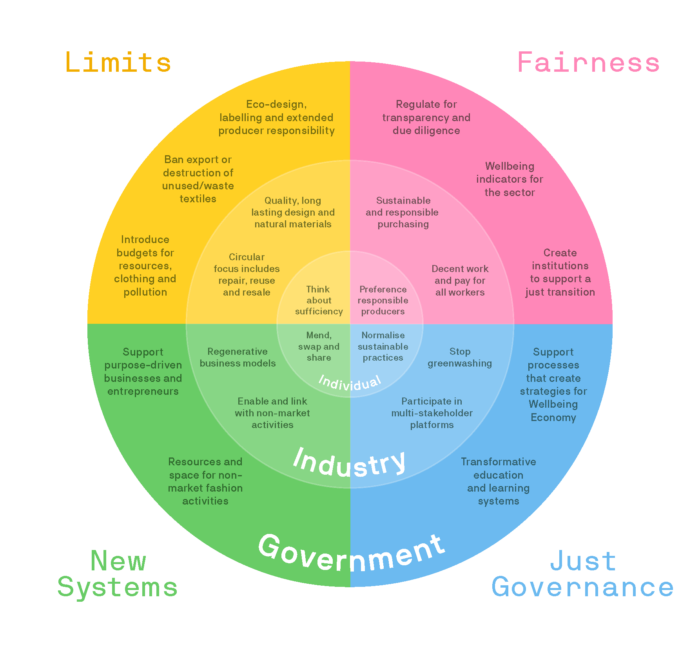

Taylor: Envisioning a wellbeing economy for fashion involves adopting four key principles outlined in our report, “The Wellbeing Wardrobe.”

First, we need to establish limits. In a wellbeing economy, we set resource use and consumption boundaries while showing people how to live well within these limits. Examples include embracing slow fashion, supporting garment repair, and raising awareness about reusing and refashioning clothing. Improved data transparency is also crucial to track progress.

Next, there is a need to promote fairness. To ensure global and intergenerational fairness, we need equitable wealth distribution systems. This involves ethical fashion initiatives that advocate for fair work conditions and discussions about the benefits of local production.

Third, we must create healthy and just governance models. Robust and participatory governance processes emphasising inclusivity, open dialogue, and diversity are essential. These processes encourage capacity-building and stakeholder engagement at all levels of the fashion industry.

And finally, we must embrace new exchange systems: Innovative models ensure the fashion industry thrives while meeting human and environmental wellbeing needs. Examples include B-corps, ecopreneurs, swapping, and second-hand shopping, all aimed at creating a sustainable and equitable fashion ecosystem.

FR: How can the concept of the wellbeing economy address global inequalities in the fashion supply chain?

Taylor: This is a crucial aspect of the wellbeing economy’s impact. When transitioning to a wellbeing economy, we must consider change’s global and local implications.

For example, while localising production can lead to improved working conditions and higher garment prices, it also has short-term consequences for workers in the Global South who depend on these jobs for their livelihoods.

FR: So, it’s about finding a balance and considering the impact of change on all stakeholders, including those in vulnerable positions. Now, let’s explore the roles of different actors in this transition. Are there existing elements of the fashion industry indicative of the transition to a wellbeing wardrobe?

Taylor: Absolutely! The fashion industry shows several promising signs of evolving towards a wellbeing-focused wardrobe.

First, there’s the shift from excessive shopping to building emotional connections with clothing. It’s not just about buying less; it’s about forming meaningful attachments to your wardrobe pieces.

Another critical aspect is the consideration of fibre choices. Many are opting for natural fibres as a wellbeing-friendly choice. However, it’s essential to recognise that, given our current consumption levels, we cannot only rely on natural fibres. This highlights the importance of both sustainable materials and reducing the overall production of clothing.

Slow fashion is also gaining momentum, focusing on timeless designs and high-quality production. The goal is to create garments that can last for years, with adaptability and durability, built to accommodate changing bodies and needs.

Efforts to repair and care for existing garments are gaining traction, too. Mending, repairing, and adopting better laundry habits extend the lifespan of clothing, challenging the notion that garments are disposable. Brands and educational institutions are taking on a crucial role in teaching these essential skills.

Collaborative consumption models, such as fashion rental or subscription services, also challenge the industry’s growth-dependent mindset. These models emphasise access over ownership, providing brands with alternative revenue streams that rely on something other than continuous new garment production.

FR: Now, let’s explore the role of brands in this transition. How can brands support this transition to a wellbeing economy?

Taylor: Now, this is a big one, and it’s clear that brands have a pivotal role in driving this transition. One of the biggest things brands can do is lead the charge by reducing production and putting quality front and centre. It’s the mantra of prioritising quality over quantity. Transparency and fighting greenwashing is also essential to building trust with consumers and stakeholders.

FR: Let’s shift our focus to policymakers. What specific actions can policymakers take to support this transition?

Taylor: Policymakers can play a pivotal role in promoting transparency and wellbeing. By advocating for greater transparency and fairness in supply chains, they can drive the adoption of more ethical and sustainable practices. Additionally, policymakers have the opportunity to empower and support purpose-driven initiatives, while also fostering strategies that prioritize wellbeing.

FR: And finally, as individuals, how can we contribute to creating a wellbeing economy for fashion?

Taylor: There are a number of different steps to be part of this change. One of the most significant actions is reducing resource use and consumption. When buying clothes, we can look to the slow fashion movement and prioritise quality and longevity in our clothing choices. We can also make efforts to repair and care for the garments we already own that can significantly extend their lifespan.

We can also consider alternatives to ownership, such as fashion rental and other collaborative consumption models that provide access and allow us to enjoy fashion without buying new items. And, of course, don’t be afraid to get creative with your fashion choices and shop your own closet. The most sustainable garment is the one you already own.

FR: Reducing consumption and making #LovedClothesLast is a powerful way to minimise our fashion footprint. What’s another step individuals can take?

Taylor: We can advocate for more sustainable practices in your day-to-day life and share your knowledge and questions about the industry with your communities. It is important to recognise that we not only have power as consumers, but also as citizens. Asking questions like #WhoMadeMyClothes and #WhatsInMyClothes, supporting initiatives like Good Clothes, Fair Pay, and contacting your elected representatives about the issues you care about are just a few of the ways you can use your voice to demand change.

FR: Sharing knowledge and having these questions with others can definitely create a ripple effect of positive change. Now, to wrap up, what’s the key takeaway you’d like our readers to have?

Taylor: The fashion industry faces significant sustainability challenges, but solutions and opportunities for positive change exist. Collaboration and a shift towards a wellbeing economy can pave the way for a more sustainable and equitable fashion future.

You can learn more about the Wellbeing Wardrobe here.

Header image: @j_creativestudio featuring a quote from @OrsoladeCastro