The Labor We Wear: Artist Rachel Breen Shares the Stories Behind our Clothes

Intro by William Persson

Our Fashion Revolution USA Director of Operations and Community Ashleyn Przedwiecki interviewed Rachel Breen about her work “The Labor We Wear,” which highlights the relationships between the garment industry, workers in the supply chain, and fashion consumers. They address what inspired the pieces and how incidents like the Rana Plaza Factory Collapse have influenced her drive to tell the stories of garment workers. This Q&A has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

ASHLEYN P.: I watched your talk with the Minneapolis Institute of Art and I was so drawn to how you incorporate ethics and social justice into your artistic approach. Can you talk more about your background and what led you to create your current show, The Labor We Wear?

RACHEL B: For years, long before I thought much about garment workers and before the Rana Plaza Factory Collapse, I used my sewing machine as a drawing tool. I still think of my sewing machine as my third arm. When the Rana Plaza Factory did happen, I remember thinking about what it would feel like to be in my 4th-floor studio in NE Minneapolis, sitting at my sewing machine, and have the floor give way beneath me. My horror over the Rana Plaza Factory Collapse and the lives lost and thousands injured gave rise to a deep desire to respond and speak out.

The idea for this exhibition also came from a recognition that the ways garment workers are exploited are not new -that garment workers have been mistreated since the birth of the industrial revolution. I realized this in part because I connected this disaster to a disaster I grew up knowing about: the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire that took place in 1911 in New York City. One hundred forty-six mostly Jewish and Italian immigrants died in this fire, one of the worst worker disasters in the US at that time. I wanted to make work that showed that Americans are not removed from the exploitation of garment workers -but are linked historically as well as through the clothes that we wear.

A.P.: Can you share more about your experience in Bangladesh after the Rana Plaza factory collapse?

R.B.: My experience in Bangladesh was very powerful. I’ll share a few things that were especially important lessons for me. One, is that women suffer daily physical and verbal harassment, are frequently not paid what they are owed and daily work in factories that are extremely unsafe -to a degree that I had not realized. Death and injury happen all the time and we just don’t hear about it. The need for and importance of unions in Bangladesh came into clear focus for me. The labor union movement in Bangladesh is quite nascent but is more important than ever because it is the only collective voice for these women and the only clear way to empower them to address unfair wages and working conditions.

I traveled to Bangladesh with my friend and writer Alison Morse. Both of us are Jewish and were making this connection between the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire and the Rana Plaza Factories collapse. We shared this story with many of the women we met when we would explain why we were there. Many of them told us we should meet with the Tazreen Factory fire survivors because that tragedy was even more familiar to the Triangle Shirtwaist fire so we did. Learning about this other tragedy it dawned on me that there were probably so many disasters that I did not know about. We did interview many survivors of the Tazreen Factory fire and it was just as heartbreaking as speaking to the survivors of the Rana Plaza Factory Collapse. I was constantly surprised by the willingness of women to share their stories. Women want to be heard.

A.P.: This exhibition is one of many you’ve worked on that focuses on the untold stories of garment workers and spotlighting the people behind our clothing. What was the inspiration behind this? And how do you turn an idea into an art piece or a full exhibition?

R.B.: The more I have learned about the global garment industry the more I have felt outraged and deeply concerned about the treatment of workers, and the ramifications of overproduction on the part of corporate brands, overconsumption by the American public, the waste all this causes, and how it impacts our planet. It is absolutely horrifying, and I hope that my work can contribute to behavior changes, but more importantly, lead to policy changes that address this industry.

As an artist, I am very curious and interested in how materials convey meaning. Once I began to work on this issue I thought a lot about the materials that would help tell the many aspects of the story of Rana Plaza, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, the daily labor of garment workers, and our connection, as consumers to these stories. I spend a lot of time in my studio playing with materials: taking things apart, arranging them, rearranging them until they start to speak the way I want them to. This focus on exploring materials in my work and the public response to it has inspired my continued journey of making work on this subject.

A.P.:What are you hoping people will come away with after exploring one of your exhibitions?

R.B.: I hope that people feel moved in some way. I hope the work encourages people to reflect on the themes in my work and that it provides them with a larger lens through which to look at the world and their (our) things.

A.P.: Did you imagine your installation to become as popular and moving as it has been to so many people?

R.B.: That is a great question! No, I imagined and hoped but I did not know what an impact the work would have. With a project this large, you don’t really know what it will look like until it’s finished and installed. I was so nervous! I spent months working on it and finally when it was up I couldn’t believe how powerful it was — I was so happy and also sorrowful — you can’t look at the work and not feel both emotions.

A.P.: How does the sewing machine play a role in your work as an artist?

R.B.: I am interested in the creative possibilities of the sewing machine. I use it to draw, create installations and initiate socially engaged public projects. I am a maker, yet much of my work involves the opposite: I “unmake” things and “dismantle” ways of seeing and believing. I am interested in the sewing machine as a deeply symbolic and also (im)practical object.

A.P.: You use art as a tool for social change, can you talk more about how you see the relationship between art and social justice movements?

R.B.: I think that art can help the public look at a problem or a situation with new perspectives and in a way that is empowering. Successful community organizing requires building power, and I believe building power begins with having new insights and believing that change is possible.

A.P.: Do you have any advice for young designers, artists, or leaders as they challenge/confront the deeply ingrained issues within our current fashion industry?

R.B.: Work from a place of community. That means building community so that you can collectively challenge, confront, advocate and build towards your vision. Have a vision of the change you want to see, otherwise, you won’t have a sense of direction. Engage, be open to being wrong and be brave!

A.P.: What is next for you as you pursue a continuation of this body of work? How do you hope it might unfold and drive change?

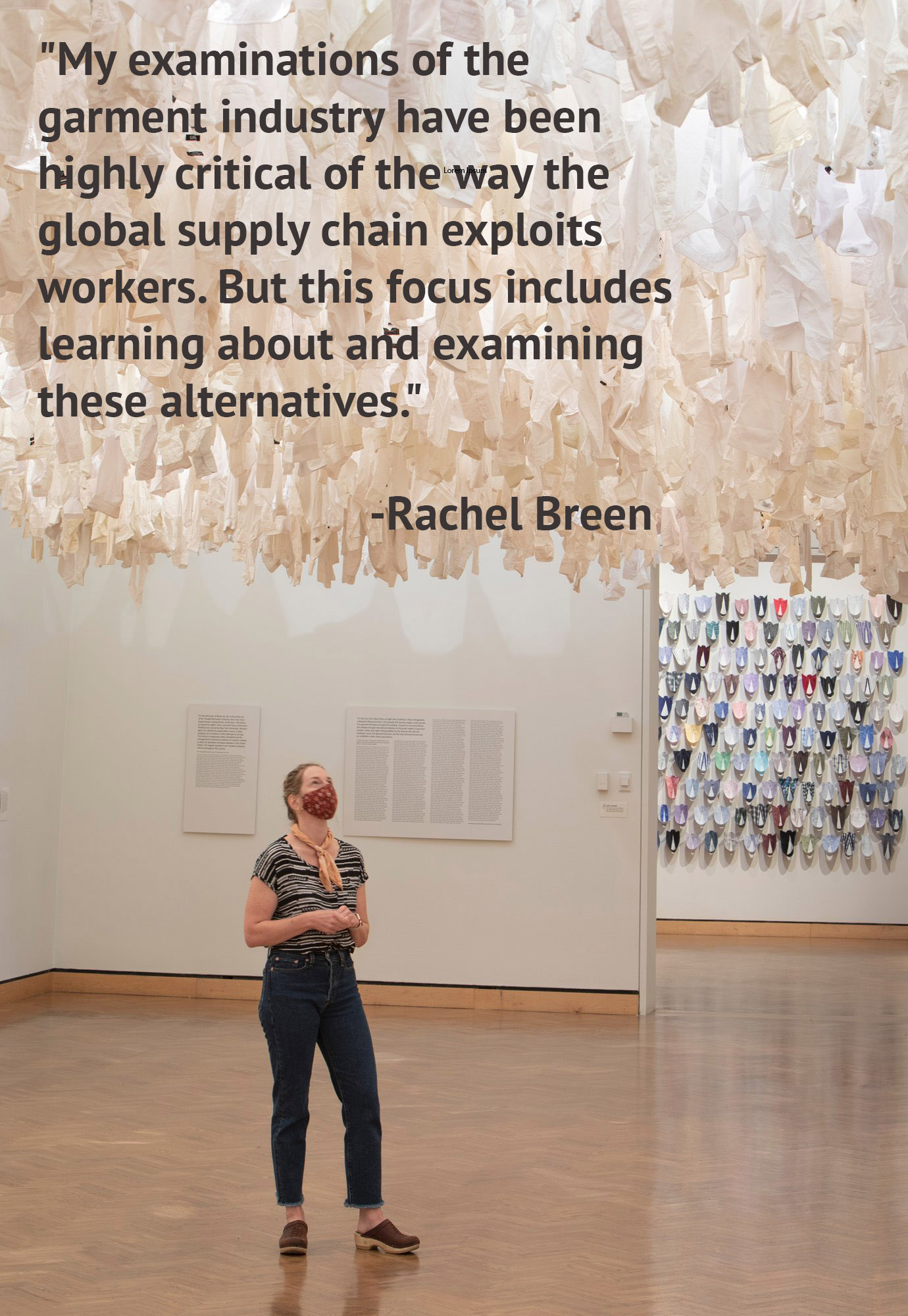

R.B.: My examinations of the garment industry have been highly critical of the way the global supply chain exploits workers. But this focus includes learning about and examining these alternatives. I’m currently envisioning the development of visual language that explores alternative economic models to capitalism.

Rachel Breen received her MFA from the University of Minnesota and is involved in creating her pieces using non-traditional materials and exhibition spaces that aim to inspire community engagement in social justice initiatives. In “The Labor We Wear,” she utilizes clothing to hold consumers accountable for the life cycle of garments, from unsafe working conditions to textile waste. The work makes these relationships visible in order to break the cycle.