La semana pasada en Copenhagen Fashion Summit, Juan Orlando Hernández, Presidente de Honduras hizo la siguiente invitación: “Si quisieran ir a Honduras a conocer por ustedes mismos, yo los recibiré personalmente en el aeropuerto”.

Ignorando las molestias en la parte posterior del auditorio que llamaron “Señor Presidente, detenga a los militares de asesinar a activistas” el Presidente de Honduras lanzó para promocionar el país como líder de exportación de prendas a Estados Unidos de América y tiene el objetivo de exportar más al mercado Europeo. La industria del vestir y textil es parte del nuevo plan Honduras 2020, un proyecto de $3.4 miles de millones, que tiene como meta hacer que Honduras sea la elección de muchas marcas para proveer de forma sustentable. “Haremos esto mediante un verdadero modelo sustentable, enfocándonos en factores clave como condiciones laborales sustentables, protección del medio ambiente, utilizando la última tecnología para reducir el consumo de los recursos, cambiando los combustibles a energías renovables” mencionó Juan Orlando Hernández, quien continuaba enfatizando el objetivo de su país por tener el 80% de sus energías de origen renovable para el 2020.

El compromiso por reducir los combustibles no renovables claramente no exenta al mismo Presidente, quien rentó un jet de lujo para ir a la conferencia de Vista Jet, entre sus clientes tienen a celebridades como Beyonce y los Beckham. La presentación del Presidente le costaría $360,000 viajando solo, de acuerdo con la información del sitio, dando esto decenas de críticas en la página de Facebook de Copenhagen Fashion Summit.

El Presidente seguía mencionando a las 1200 personas del público haciendo hincapié en cómo su país toma muy en serio el lado social de la sustentabilidad. “Gozamos de un excelente y seguro ambiente de trabajo y cuidar a nuestra gente es nuestra principal atención y responsabilidad”.

El Presidente llegó a decir que Honduras era “el segundo lugar más justo para la producción de prendas de vestir”. Después de un correo electrónico al Americas Apparel Producers’ Network, he recibido una respuesta del Director General Mike Todaro quien aclaró que el Presidente se refería al AAPN Asia/Americas Report Card. Honduras llegó al 2º lugar en el informe. Sin embargo, por lo que yo puedo ver a partir de la información en línea, sólo uno de los 8 criterios se refiere a cumplimiento social y sostenibilidad y los otros 7 incluyen elementos como el coste, la velocidad y el desarrollo de productos.

De acuerdo con War on Want, 53% de los trabajadores en maquilas o fábricas de ropa, en Honduras son mujeres jóvenes de comunidades desfavorecidas que tienen poca educación. La mayoría no son conscientes de sus derechos, la explotación es frecuente y los trabajadores están desmotivados a formar sindicatos. Solidarity Center dice que los sindicalistas son constantemente amenazados, intimidados, extorsionados e inclusive asesinados, y los criminales rara vez puestos a disposición judicial.

31 sindicalistas han sido asesinados y 200 heridos en ataques desde el 2009, de acuerdo con la federación de sindicatos AFL-CIO. De hecho en Marzo del año pasado en Departamento Americano del Empleo publicó un informe documentando abusos a los derechos de los trabajadores en Honduras. El informe detalla muchos casos donde los empleados hondureños relacionados en actos de discriminación anti-sindicalistas, imponiendo pactos anti-sindicalistas para frustrar negociaciones colectivas, así como casos donde no se pagan los salarios, exigir horas extras y numerosos abusos en cuanto a salud y seguridad laboral.

En promedio los salarios de las maquilas son equivalentes al 37% del costo de la canasta básica de Honduras. Además la diferencia entre los salarios de los trabajadores de maquilas y los de las otras industrias está en crecimiento. La competencia a la base continuará a menos que tomemos un acercamiento para tener un salario para vivir, trabajando con los gobiernos y sindicatos para ajustarlo de manera legal, imponiendo un salario mínimo en su país que asegure que los empleados puedan cubrir sus necesidades básicas.

Sin transparencia en la cadena de suministro y sin compromiso de los dueños de las marcas de moda y las fábricas de invertir en mejores condiciones laborales, los salarios y derechos de los trabajadores se mantendrán desempoderados y no podrán negociar de manera independiente sus condiciones laborales.

La industria textil y de la moda sin duda a traído trabajos al país, pero no son buenos empleos. Frecuentemente se discute si cualquier trabajo es mejor que no tener trabajo, pero no hay motivo por el cual no crear buenos empleos, trabajos con dignidad, sin tener un impacto en el precio de venta. El hecho de que la gente está en una situación difícil no es motivo para explotarla. Una Fashion Revolution es necesaria dado que las marcas, incluso las mejores marcas quienes están trabajando de manera proactiva hacia un salario para poder vivir, nunca cambiarán el sistema.

Deberían venir a ver si estos empleos realmente ayudan a las personas a salir de la pobreza, con los salarios que reciben, sin derechos laborales. ¡No tienen un lugar para sentarse a comer, tienen que comen en las calles y regresar al trabajo! ¡En verdad se creyeron lo que este hombre fue a decir a su evento! Comentó RS Briose en la página de Facebook de Copenhagen Fashion Summit.

En respuesta a RS Bruise y otros ciudadanos Hondureños quienes comentaron sobre la visita de Juan Orlando Hernández a Copenhagen Fashion Summit: Sí, visitaremos y veremos con nuestros propios ojos #whomademyclothes #quienhizomiropa. Iremos a ver si Honduras es realmente uno de los lugares con las mejores condiciones sociales en el hemisferio oeste para la producción de ropa y textiles, tal y como se indica en la presentación del Presidente.

Estoy lista para aceptar el ofrecimiento del Presidente de Honduras para visitar las fábricas de su país y confío en que mantendrá su palabra. Presidente, nos vemos en el aeropuerto.

It is not often that the life of Beyoncé and academic researchers intertwine – the chances are even more remote, when the research site in question, Sri Lanka, often rightly avoids the negativity associated with the global supply chain. Media reports record how Beyoncé justly supports the feminist cause for gender equality in pay. Yet by her braving into the world of branded gym wear (Ivy Park) to support and inspire women, she was opening herself to media scrutiny about how empowered its workers may be. While the media scrutiny may be warranted, the media’s representation of Sri Lankan workers is a partial rendering that flattens the very labour voices these interventions claim to champion.

On 8 May 2016, The Sun on Sunday carried a news item with the headlines that “Sweatshop ‘slaves’ earning just 44p an hour making “empowering” Beyoncé clobber”. Not being a reader of tabloids, I came to know of it, when an inquiry came my way from Broadly, requesting for input for a piece that it was being put together. In the hope for a nuanced intervention to the early news foray –from the Sun to the Metro, I assented. In the conversation with Siri Kale, we overviewed positive attributes to Sri Lanka’s apparel sector, signaling that it is ability to do so is associated with multiple factors – from a highly educated labour force to high standards in building regulations to protective labour legislative framework. All features of state policies in the social development and labour legislation; facets often downplayed in an age of corporate social responsibility. We also talked about the Achilles heels of Sri Lankan apparels – the lack of living wages and the inability of most workers to freely associate and enter into collective bargaining (i.e. unionise).

In the eventual output that came out of Broadly, the positives of Sri Lankan apparels or the potentially enviable Sri Lankan context was edited out. Hence, there was only one direct quote registering how MAS, a supplier/producer of Ivy Parks, has fantastic factories, is attentive to the built space, and how it is usually considered to be top of the supplier base in Sri Lankan. Otherwise, with a vaguely problematic title, the emphasis was on the lack of living wages and unionisation.

The absence of a living wage and the impossibility of unionisation are two points emphasised earlier in a report that came out of an ESRC-funded research, although there made within a context. I also emphasised how the positive adherence to ethical trade regimes and Sri Lankan apparels ability to do so having much to do with historical labour struggles, labour legislative frameworks and state policies towards our social development fabric. The centrality of labour geographies in making capitalism, à la Andrew Herod, was emphasised to accentuate how labour has agency in shaping capitalist development processes.

This nuanced reading of Sri Lankan apparels was met with wrath by an important union in Sri Lanka, with a pro-union friendly journalist hounding me with local media interventions in a bid to vilify the research. This stance was presumably because it dented the union’s ability to portray Sri Lankan apparels through a black and white lens. Shades of grey in labour politics was a faux pas, as a UCU academic member I was to learn – in a somewhat harsh way in my local research setting. Almost four years later, the partial rendering of my views by Broadly led to a message from a senior manager at one of my research sites to question my stance. While this communication was not unfriendly, I still had to point to him that the two lapses I had noted are already in the report that also helped his factory achieve a higher certification. It, however, made me then dig deeper into how this story had developed in the media.

From the Guardian to the Independent to the Telegraph, the emphasis was on Sri Lankan workers earning abysmally low amounts per hour, their slavery and the ability for consumers to change all these woes of the supply chain – where, according to the Guardian, Beyoncé was not to be blamed. Holding Beyoncé personally responsible for inequities in uneven capitalist development and the supply chain is simplistic analysis. This is beyond doubt. Yet the fact that the media and campaigners alike continue to promote the idea that consumers can single-handedly change the global labour division and continue to flatten the voice of labour by reducing workers to a homogenous category or to slaves is equally naïve. It is a representation that misses the very labour agency or conditions of possibility that made a single woman worker articulate views on empowerment and the lack thereof in her labouring life.

Feminists, Ethel Brooks and Dina Siddiqui, have emphasised this point previously and yet it continues to evade the attention of media and campaigners. The fact that Sri Lankan labour get paid a monthly minimum wage negotiated through a tripartite Wages Ordinance Board and hence are not paid an hourly wage or indeed a piece rate system was wholly absent from almost all media interventions. The woman’s description of her deplorable (private) boarding conditions is then stretched to categorize her situation as akin to slave labour. The elasticity of campaigner interpretations would require a leap of faith for any intelligent and careful reader. Nowhere in the public domain do I find the worker saying that MAS was providing boarding and that her mobility was severely restricted. Features usually absent in the Sri Lankan apparel trade, partly because many do not provide factory-based boarding facilities and partly because workers would not tolerate factories where they were locked up.

What then of Sri Lankan apparel workers? In contrast to the blasé narratives we are provided with, the reality of Sri Lankan labour is more complex and nuanced. Sri Lankan apparel sector draws upon an important and impressive social development agenda adopted by the Sri Lanka state for decades – giving the industry a highly skilled and educated labour force. It also draws upon relatively strong labour legislation, an outcome of labour struggles and movements from yesteryears, which thwarts the worst excesses of uneven capitalist development. These are facets that enable Sri Lankan apparels to make bold claims around producing “garments without guilt”; child labour, for instance, is non-existent in the industry because of state-provided free education and our legislation requires children to be in school until 16 years of age. Yet it also remains the case that with the weakening power of unions and gradual erosion to protective labour legislation, the risks for Sri Lankan apparels to fall off its cultivated mantle is real. The neglect of state protection towards labour given its absence of regulating private boarding houses or extending weekly overtime hours, equally matter in process of uneven capitalist development. Equally, so long employers have a stranglehold on the Wages Ordinance Board, worker wage increments rarely, if ever, have kept pace with inflation. The absence of a living wage then is likely to remain the Achilles heel of the Sri Lankan garment industry – making it potentially vulnerable to all other wild accusations, whether these hold water or not.

At the Copenhagen Fashion Summit last week, Juan Orlando Hernández, President of Honduras, issued the following invitation: ‘If you would like to go to Honduras to look around for yourselves, I will be personally at the airport waiting for you’.

Ignoring the heckler at the back of the room who called out ‘Mr President, stop the military from murdering community activists’ the President of Honduras launched into a promotion for his country as a leading garment exporter to the US and his ambitions for a larger European market share. The garment and textile industry is part of the newly launched Honduras 2020, a $3.4 billion project which aims to make Honduras into the country of choice for brands and retailers wishing to source sustainably. ‘We will do this through a real sustainable model focussing on key topics such as sustainable working conditions, protecting the environment, using the latest technology to reduce consumption of resources, moving from fossil fuel to renewable energy sources’ stated Juan Orlando Hernández, who continued by highlighting his country’s ambition to source 80% of its energy from renewable sources by 2020.

The commitment to reduce fossil fuels clearly doesn’t extend to the President himself, who rented a luxury jet to fly to the conference from Vista Jet, whose clients include celebrities such as Beyonce and the Beckhams. The President’s short presentation would have cost $360,000 in travel alone, according to one source, prompting dozens of critical comments on the Copenhagen Fashion Summit Facebook page.

The President continued to address the 1200-strong audience by underlining how seriously his country takes the social side of sustainability. ‘We enjoy an excellent and safe work environment and taking care of our people is our main focus and our responsibility’.

The President went on to say that Honduras was ‘the second most fair location for garment production’. After an investigatory email to the Americas Apparel Producers’ Network, I received a response from Managing Director Mike Todaro who clarified that the President was referring to the The AAPN Asia/Americas Report Card. Honduras came 2nd overall in the AAPN Report Card which is completed by sourcing executives. However, as far as I can see from online information about the Report Card, only one out of the 8 criteria relates to social compliance/sustainability and the other 7 include elements like cost, speed and product development.

According to War on Want 53% of garment workers in maquilas, or garment factories, in Honduras are young women from deprived backgrounds who have little education. Most are unaware of their rights, exploitation is widespread and workers are actively discouraged from joining unions. The Solidarity Center says trade unionists are routinely threatened, intimidated, harassed and even murdered, with the criminals rarely brought to justice.

31 trade unionists have been assassinated and 200 injured in attacks since 2009, according to the umbrella federation for US unions AFL-CIO. In fact, in March last year the US Department of Labour issued a damning 143 page report documenting widespread and serious violations of labour rights in Honduras. The report detailed numerous cases where Honduran employers engaged in acts of anti-union discrimination, imposing non-union pacts to frustrate collective bargaining, as well as cases of non-payment of wages, forced overtime and numerous occupational health and safety violations.

On average, the wages earned in maquilas are equivalent to only 37% of the cost of the basic basket of consumer goods in Honduras. Moreover, the gap between wages for workers in maquilas and those in other industries is widening. The race to the bottom will continue unless we take a systemic approach to the issue of a living wage by working with governments and unions to set a legal, enforceable minimum wage in their country which ensures workers can meet their basic needs.

Without supply chain transparency and a commitment from fashion brand owners and factories to invest in better working conditions, living wages and workers’ rights, garment workers will remain disempowered and unable to independently negotiate labour conditions.

The garment and textile industry has undoubtedly brought jobs to the country, but not necessarily good jobs. It is often argued that any job is better than no job, but there is no reason why we can’t be creating decent jobs, jobs with dignity, without any significant impact on the retail price. The fact that people are desperate isn’t an excuse to exploit them. A Fashion Revolution is needed because brands, even the best of the brands who are working most proactively towards a living wage, will never change the system.

‘You should come see if this jobs really help people get out of poverty, with the kind of wages they make, with no labor rights. They are not even given a place to have their meals, they have to take lunch in the street and then come in back to work! Did you really believe what this man went to say to your event!’ commented RS Bruise on the Copenhagen Fashion Summit Facebook page.

So, in response to RS Bruise and all the other Honduran citizens whose commented on the visit of Juan Orlando Hernández to the Copenhagen Fashion Summit: Yes, we will come and see for ourselves #whomademyclothes. We will come and see whether Honduras really is one of ‘most fair social locations in the Western hemisphere for garment production’, as claimed in the President’s presentation.

I am ready to take the President of Honduras up on his offer to visit garment factories in his country and trust that he will keep his word. Meet me at the airport, Mr President.

Moral. It’s not a word we use very often, especially when we talk about fashion. Fashion comes with many adjectives attached: fabulous, iconic, elegant, sumptuous, dashing, nostalgic, effortless… but moral is rarely one of them.

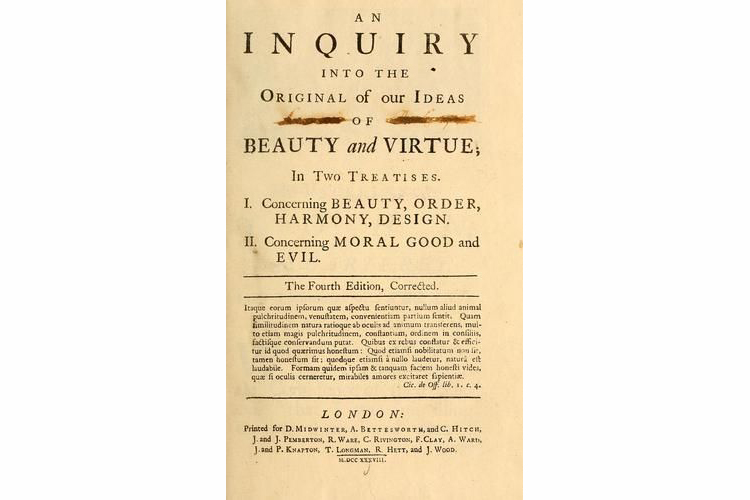

In 1725, Rev Francis Hutcheson wrote An Inquiry into the Original of our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue. In his opinion, an outward perception of beauty was impossible without an inner sense of beauty as well. He called this as a ‘moral sense of beauty’ and, importantly, he understood it as something which could be altered by information and reasoning.

In the mid 18th Century, the first examples of fashion press appeared in Paris with publications like Le Journal de la mode et du Goût. This was the start of the connection between fashion and taste, fashion and ideals, fashion and individualism. It was also the beginning of our moral disengagement as community values gave rise to individual values. The fashionable young women portrayed on its pages embodied the rise of consumer culture.

This desire for new clothes was not confined to 18th century Europe. In Latin America, clothing was recognised as a symbol of social status and prestige and was manipulated by the marginal sectors of society in order to become more socially, economically, politically and culturally reconised.

An overwhelmed husband wrote to the Mercurio Peruano in 1791 setting out the precarious financial situation in which he found himself as a result of his wife’s fashion taste. He protested her need to have a different dress for every social occasion. Whilst his wife had garnered admiration from society in Lima, the husband was unable to pay his debts. For the wife mentioned in the letter, clothing had become a vehicle to make herself visible in a male-dominated society, expressing her status and social freedom.

Our desire for fashion has certainly not diminished in the ensuing 200 years. What has changed, however, is our proximity to, and awareness of, the impact of our purchases.

In the 19th Century, a sweater was an employer or middleman who abused his workers with monotonous work, unhealthy or unsafe conditions and poverty-level wages. The desire of manufacturers to pay the lowest possible wage, coupled with a huge number of rural poor and immigrants looking for work in Britain and the US, produced a climate ripe for the exploitation of workers and the establishment of the first sweatshops. Sweating came to describe work which lacked respect for the human factor. A House of Lords Select Committee on the Sweating System was established in 1889 which publicly exposed the poor conditions in which garment workers toiled. Debate over the morality of production led to unionisation and concerned consumers called for reform. For a while, things got better.

The 20th Century saw waves of trade liberalisation policies starting after World War II, resulting in the offshoring and outsourcing of production to Asia and Latin America. With the relocation of manufacturing came the abrogation of responsibility. It has been endlessly debated whether brands and retailers are morally and legally responsible for their workers overseas.

It has also been questioned whether the fashion consumer in the West is morally responsible for the poor working conditions and unsafe working practices in factories in developing countries. Many of us suspect that the clothes we wear have been made in a sweatshop. Does this affect our moral responsibility? In his book Profits and Principles: Global Capitalism and Human Rights in China, Michael A Santoro argues that ‘consumers are a very big part of the web of moral responsibility for human rights. Ultimately it is consumers who wear the shoes and clothes manufactured in sweatshops… What is needed is a real partnership between companies and consumers, based on a very simple moral compact. Companies must agree to manufacture products in compliance with human rights codes and consumers must agree to place monetary value on such compliance. Both sides of the compact are necessary to safeguard human rights’. In other words, equity for all must become a universal standard and we all bear responsibility for ensuring this happens.

My relative Dyddgu Hamilton (pronounced Dithky) was a close friend of Hilaire Belloc and his wife Elodie. Dyddgu became Belloc’s secretary and subsequently his lifetime correspondent – there are hundreds of letters between them.

I’ve been a voracious Belloc reader for many years – he was a prolific writer with well over 100 published books. I recently came across this quote he wrote in the Sahara, and it struck me that the description of the barbarian could so easily apply to the fast-fashion addict who takes no responsibility and gives no thought to their expanding wardrobe.

‘The Barbarian hopes – and that is the mark of him, that he can have his cake and eat it too. He will consume what civilization has slowly produced after generations of selection and effort, but he will not be at pains to replace such goods, nor indeed has he a comprehension of the virtue that has brought them into being…. We sit by and watch the barbarian…We are tickled by his irreverence ..we laugh. But as we laugh we are watched by large and awful faces from beyond, and on these faces there are no smiles.’

Returning to Frances Hutcheson’s philosophy of beauty, his views are reflected in the worldview of indigenous peoples in the Andes where something which is beautiful is typically something which is well-balanced, something ayni. Everything in the Inca world was based on ayni, a system of exchange based on mutual respect and justice with other communities and cultures throughout their vast empire. Ayni has survived the conquest and capitalism and is still widely practised today. Beauty is about balance, and what is sustainability if not finding a balance between the desires of our generation and the needs of the next?

Before we can rediscover a ‘moral sense of beauty’ on falling in love with a new dress, we need to know that there is equity behind its beauty. To know that there is equity, we need transparency. We cannot hold the many stakeholders in the fashion supply chain to account until we can see them, and we cannot start to tackle exploitation until we can see it. That’s why Fashion Revolution is asking the question #whomademyclothes. We want to know that the clothes we buy are beautiful in every way.

The feature in today’s Daily Mail proclaims ‘Hypocrite Brand’s trendy tops made in Bangladesh sweatshop: Millionaire comic sells £60 sweatshirts from workers earning just 25p an hour’

25p an hour, surely that’s a lot more than most garment workers in Bangladesh receive? Was this just another article like the Fawcett Society T-Shirt article which aims to scandalise its readers whilst actually showing an example of what is, shockingly, accepted as best practice?

Sure enough, scroll down to the bottom of the article and it states that ‘Industry regulator, Fair Wear Foundation, says the factory is one of the best employers in the country and pays more than other less scrupulous operators’. The shocking part of this story is not the 25p an hour that the garment workers are earning, nor the 11 hour days which are routine in the industry. A Panorama investigation in September 2013 exposed the garment workers who were locked in for 19 hour shifts, with timesheets falsified to show they left at 5.30pm instead of 2.30am the next morning. Brand claims his sweatshirts are ethical on his website, but what does ethical mean? Is paying 15% more than a minimum wage which will keep the worker in absolute poverty really an acceptable reason to label a garment ‘ethical’?

The best is nowhere near good. It is nowhere near good enough. The legal minimum wage in most garment-producing countries is rarely enough for a worker to live on. It is estimated that the current minimum wage in Bangladesh still only covers 60% of the cost of living in a slum. A garment worker receiving the minimum wage who has a child to look after will be classified as living in extreme poverty. Not only do minimum wages keep garment workers in a cycle of poverty, but they also add to the pressure to work long overtime hours. There is a direct correlation between working hours and accidents at work, but many of the health and safety issues resulting from excessive overtime are not even visible, such as mental health problems and increased exposure to chemicals.

In the Labour Behind the Label report Tailored Wages (March 2014) just 4 of the 40 leading international clothing brands asked were able to demonstrate work they were doing that could lead to a living wage. Brands who are doing little or no work towards a living wage, scoring between 0.5 and 5 out of a maximum score of 40 were Aldi, Debenhams, Esprit, Gucci, Mango, Matalan, Pentland (inc. Speedo, Hunter), VF Corporation (inc. Lee, Wrangler, The North Face, Timberland), and Versace. The Behind the Barcode report from April 2015 found that just 12% of fashion brands surveyed could demonstrate any action at all towards paying wages above the legal minimum and, even then, only for part of their supply chain.

At Fashion Question Time, organised by Fashion Revolution in the Houses of Parliament on 26 February 2015, Catarina Midby, Global Head of Sustainable Communications at H&M said ‘We believe that the garment industry is the way out of poverty’. Jenny Holdcroft, Policy Director at IndustriALL Global Union responded by saying “I think it’s clear that the brands that have driven this sort of sourcing model have not paid any attention to wages… The factory owner who also wants to make a profit out of this wants to see where they can squeeze. Often they can’t squeeze the materials because the brand can specify what the materials are and where they come from, they can’t squeeze on overhead costs like rent, electricity, taxes. So where does the squeeze come? There’s really only two areas: their own profit margin or workers’ wages. And this is not something that the brands have ever really unpacked”.

The race to the bottom will continue unless we take a systemic approach to the issue of a living wage by working with governments and unions to set a legal, enforceable minimum wage in their country which ensures workers can meet their basic needs. A Fashion Revolution is needed because the brands, even the best of the brands who are working most proactively towards a living wage, will never change the system.

So how much more would we have to pay for Russell Brand’s sweatshirt if he had paid the garment workers a living wage? It has been estimated that putting as little as 25p onto the cost of a garment made in Bangladesh would provide the producers with a living wage and pay for factories to meeting fire and building safety standards. Three-quarters of those questioned in a YouGov/Global Poverty Project survey said they would be likely to pay an extra 5% for their clothes if there was a guarantee workers were being paid fairly and working in safe conditions.

As well as the wage issue, there is also the issue of stuff, all this stuff. Do we really need another load of sweatshirts? Cheap, possibly badly made, polluting, sweatshirts? Why doesn’t Russell Brand, who is clever enough and original enough, or so we are lead to think, find a better product to sell to raise money and awareness? Why, instead of promoting his own ‘brand’ of completely unnecessary clothes, didn’t he take a different approach? Why not sell his own stuff, from his own wardrobe for charity as Liberty London Girl has done recently, as well as that of his friends and celebrity pals. Why couldn’t he print on previous season’s stock from one of the hundreds, if not thousands, of young British designers struggling to sell at all?

The more we make, the more we throw, and no charity on this planet can possibly benefit if we are encouraging a system which is faulty from start to finish, where bad products are ill-conceived and end up in landfill, or being shipped to developing countries where they undermine the local textile trade which some of those same charities are simultaneously trying to support.

What this article in the Daily Mail does demonstrate is why we urgently need a more transparent fashion industry. The sweatshirts were labelled Screenprinted and Produced in the UK, but the label in the sweatshirt says Made in Bangladesh. Labelling laws are incredibly lax and even doing as little as sewing on a label in Italy could mean the garment can be labelled Made in Italy, even if the majority of the production is done elsewhere. The fashion supply chain is so murky that we, as consumers, have very little way of knowing who really made our clothes and if we don’t know who made them, we can’t begin to find out how much they were paid and in what conditions they are working. Without investigations like this one by the Daily Mail, how can we know whether collections labelled as ethical, fair or conscious are really that much better than the rest?

We live in an era when any investigative journalist can unravel supply chain secrets, and it is only a matter of time before the public discovers the facts. Transparency is an issue of brand reputation, or in this case Brand reputation. To be truly transparent, we also need to be accountable and Russell Brand should step up to the mark and take responsibility for what has happened. As a ‘troubled visionary seeking to change the world’ we need him to support a Fashion Revolution, not perpetuate the status quo.

You can read the full transcript of Fashion Question Time or download the podcast here

By Fashion Revolution co-founders Carry Somers and Orsola de Castro