Fashion Revolution cada día, y en particular durante el mes de abril, nos invita a preguntamos #QuienHizoMiRopa? La respuesta parece obvia, pero no siempre está a la vista de todas y todos.

Detrás de cada prenda hay una persona, y cada persona detrás de una máquina de coser tiene una historia. Como equipo Fashion Revolution Chile creemos que es crucial reconocer la realidad de quienes diseñan, confeccionan, reutilizan y arreglan una prenda. Esas personas son la base del sistema que nos viste, y parte importante de la solución hacia un consumo más ético y responsable de la moda.

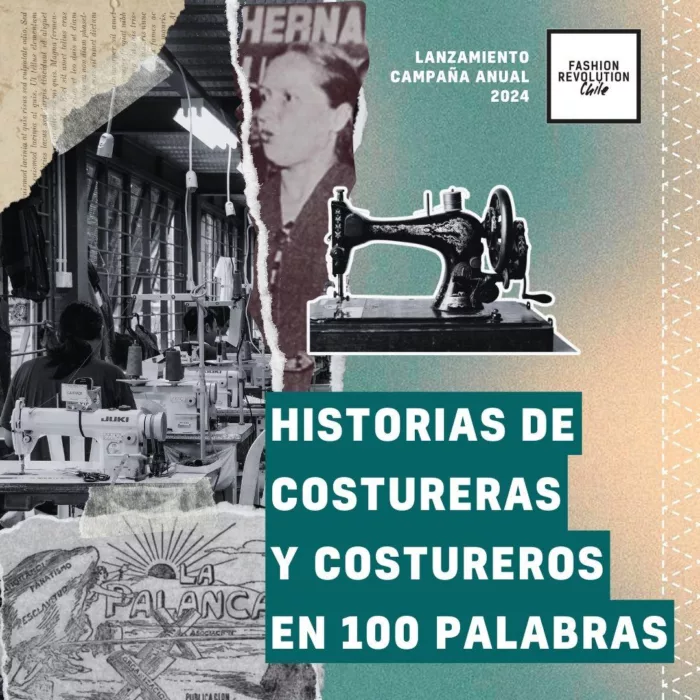

Nuestra campaña territorial 2024 “Historias de costureras y costureros en 100 palabras” nace con la intención de recoger esos testimonios, y así visibilizar la realidad a menudo olvidada de las costureras y costureros que trabajan incansablemente en la industria textil y de la moda en Chile.

Para eso, formulamos la difusión de la campaña y abrimos una convocatoria de libre participación desde el 28 de marzo hasta el 18 de abril. La que fue difundida principalmente a través de nuestras redes sociales y recibió un total de 46 historias.

Sólo en 100 palabras…

Puede ser difícil resumir la experiencia de la costura en tan poco texto, pero fueron suficientes para que algunas personas contaran cuentos, experiencias y relatos totalmente emocionantes. Algunos de ellos, entramados a una larga historia familiar, la herencia histórica del oficio y el esfuerzo que esconde el trabajo detrás de #QuienHizoTuRopa

Al finalizar la campaña, realizamos una selección de historias para exhibir en nuestro evento presencial de la Fashion Revolution Week, el día 20 de abril. Oportunidad donde nos reunimos para dialogar sobre la importancia de trabajar por una industria de la moda más sostenible, territorial y responsable, y donde también los asistentes pudieron disfrutar de seis diversos talleres, tres conversatorios, una exposición de diseño y una jornada de networking.

¡Muchas gracias a todos quienes participaron y contaron su historia!

The Embassy of Italy in the Philippines together with Home Studio Inc. and with the collaboration of the Philippine Italian Association celebrate the Italian Design Day on 9 March 2023. The first Italian Design Day in the Philippines celebrated with the theme: “THE QUALITY THAT LIGHTS UP. THE ENERGY OF DESIGN FOR PEOPLE and ENVIRONMENT.”

Three masterclasses held before the awarding ceremonies. Masterclasses that presents interior design or product design, fashion, and architecture. The ma for fashion focused at a regenerative approach on sustainable fashion. Christine Cheryl Benet, a Chairperson of Benilde Fashion Design and Merchandising Program, conducts the fashion masterclass titled fashion: “Global Futures: moving towards sustainable fashion” that discussion beyond sustainable fashion.

The main event honors 23 personalities both Filipino and Italian nationalities. The Italian Embassy honors personalities from the fashion industry that promotes sustainable and circular economy. The recognition is given to Christine Cheryl Benet, Rags 2 Riches, Rio Cuervo of Rio Taso, Prince Jimdel Ventura of Wear Forward and Spokesperson for Fashion Revolution Philippines, and Theresa Arigo for Fashion Revolution Philippines. The Fashion Revolution Philippines honored as an industry organization in fashion.

Congratulations to all the awardees who continue to promote transparency, sustainability and fair wage in the fashion industry.

Mary Pierson, a Madewell brand farmertervezésért felelős alelnöke szerint a skinny jeans csillaga leáldozóban van, és egyre népszerűbbek a bő-, vagy egyenes szárú fazonok, valamint a nehezebb, kevésbé rugalmas és nem nyúló farmerek. Bár a fogyasztók fizikai és érzelmi megnyugvást éreztek abban, hogy kényelmes ruhákba bújtak a világjárvány korai hónapjaiban, a COVID-19 nem az egyetlen tényező a bővebb, lazább darabok felé való elmozdulásban. „A skinny trend olyan sokáig volt domináns, hogy a váltás már elkerülhetetlen” – mondta Pierson.

Bő, bővebb, legbővebb

A bővebb fazonok trendjének első jelei évekkel korábban jelentek meg a kifutón, amikor az olyan streetwear orientált tervezők, mint például Virgil Abloh és Heron Preston megvették a lábukat a luxuspiacon, drága designer címkével felvértezve a műfaj jellegzetes esztétikáját.

Ha hozzáadjuk a nemek nélküli design általános érvényesítésére való igényt (amely nagymértékben támaszkodik a „dobozszerű”, munkaruha-ihlette sziluettekre), és a milleniálok ’90-es évek iránti nosztalgiáját, valamint a „csúnya” cipők térnyerését – a szélesebb, lazább, bővebb stílusok divatjának megérkezése és hatalomra kerülése nem is annyira meglepő.

A cselekmény csavarja azonban a gyorsaságban és a mindent uraló egyediségmániában rejlik: míg korábban az emberek csak jóval lassabban vettek át és szoktak meg trendeket, ma már a közösségi médiának, és a járványt követő „végre ki lehet öltözni”-felszabadulásnak köszönhetően minden felgyorsult és egyedileg determinált lett. Az így létrejövő trendciklus szerint ma már BÁRMIT viselhetünk, amit jónak látunk.

„Ebben a pillanatban nem merítünk ihletet senkitől, csak magunktól” – mondta Zihaad Wells, a True Religion kreatív igazgatója. A Ricky egyenes farmer továbbra is a True Religion első számú darabja, mert nemcsak a márka eredeti stílusára, hanem a divat aktuális alakulására is rímel. „Nyilvánvaló, hogy a farmer 2022-es új trendciklusában a múlt üdvözlése történik” – mondta Wells, hozzátéve, hogy a True Religion olyan archív stílusokkal elégíti ki a nosztalgia iránti igényt, mint a rövid szabású nadrágok a női fazonoknál vagy a férfiaknál a bő sziluettek.

A Favorite Daughter design igazgatója, Carla Calvelo egyfajta előrejelzésként kifejtette, hogy a ’90-es és 2000-es évek nagy hatást gyakoroltak erre az évre: a laza, túlméretezett, bootcut és egyenes szárú stílusok mindent visznek idén. A márka folytatja a magas derekú és hosszúkás sziluettek gyártását. Hozzátette, a testreszabott illeszkedések irányába való elmozdulás továbbra is izgatja a fantáziáját.

Ugyanez a korszak szűrődik át a 2022-es Joe’s Jeans kollekciókon is – és ez komfortzóna Alice Jackman, a márka design igazgatója számára. „Több mint 20 éve dolgozom a farmeriparban, így a ’90-es évek végén és a 2000-es évek elején tapasztalt tervezési folyamatok nagy része az első pillanattól kezdve ismerős számomra” – mondta. A Joe következő kollekciói lazább és szélesebb illeszkedést kínálnak a trendciklusnak megfelelően. A márka egy új „Heirloom” nevű szövettel is dolgozik, amely Jackman szerint kiemelkedő farmer twill vonallal rendelkezik, rendkívül puha érzettel és rugalmassággal.

„Remek erőforrásaim vannak itt Los Angelesben a vintage kapcsán, ezért mindig fedezek fel csodás koptatott darabokat, amelyekből lehet inspirálódni a modern farmerek gyártásakor” – tette hozzá.

Eközben Steffan Attardo, a márka férfi design igazgatója szerint a régi iskola divatja vezérli a Hudson Jeans új irányát. A festék fröccsenése, a roncsolás és a bevonatos szövetek a brand közelgő kollekcióinak részei lesznek, de az igazi hangsúly a bő illeszkedések kialakításán van.

„A szélesebb szárú szabás az új mainstream” – hangsúlyozta Attardo.

Közösségi háló

A múlt ihletet ad, de a Z generáció az, amely másolja és relevánssá teszi az Instagramon és a TikTokon lévő közösségi megafonjain keresztül az „új-régi” trendeket.

Noha a közösségi média már a 2000-es években is közvetítette a divatot a Tumblr-rel az élen, a jelenlegi platformok nagyobb jelentőséget kaptak a fogyasztók és a márkák számára – ezek által nemcsak közvetítik, hanem megteremtik, majd remixelik is a trendeket.

„A közösségi média valóban a folyamatosan megjelenő új trendek katalizátora lett” – mondta Sarah Ahmed, a DL1961 társalapítója és kreatív igazgatója. „Olyan gyorsan és egyszerűen oszthatók meg az új információk és innovációk, hogy nem csoda, hogy a farmertrendek ilyen ütemben változnak.”

A farmertrendek gyors átalakulása a DL1961 javára szól. Februárban a New York-i székhelyű márka bemutatta első farmercsaládját, amely hulladék pamutszálakból készült. Stílusuk középpontjában a széles szár, a bootcut, a kiszélesedő és az egyenes szabás áll. „Mivel a gyártás nálunk egy fedél alatt, a családi tulajdonban lévő pakisztáni gyárunkban zajlik, könnyen módosíthatunk, és szükség esetén gyorsan alkalmazkodhatunk az új stílusokhoz és trendekhez” – mondta Ahmed. Kiemelte még, hogy minden az információ terjedésének sebességéről és a farmergyártás technológiai fejlődéséről szól, amely lehetővé teszi számukra, hogy lépést tartsanak a változásokkal.

A buborék kipukkanása

Minden győzelmi sorozatnak vége szakad, és a tervezők arra számítanak, hogy a farmerbuborék hamarosan kipukkanhat, mint ahogyan azt már az iparágban megjelent, majd gyorsan eltűnt trendek esetében nem egyszer tapasztalhattuk.

Pierson hozzátette, korábban elvárás volt, hogy egy farmerszabás vagy -trend legalább öt évig, esetleg tovább tartson, de ma már ez nincs így, hiszen a vásárlók és az egyéb ruhaneműk trendjei is gyorsan átalakulnak. Noha nem biztos, hogy a fogyasztók gyorsan elfelejtik az aktuális farmerirányzatot – Pierson szerint a következő egy-két évben az egyenes, széles és kiszélesedő szárú farmerek lesznek a középpontban.

Így vagy úgy, de tény, hogy a farmer sosem megy ki a divatból. Ugyanakkor, mint tudjuk, a farmer negatív hatással van a környezetre, mivel szennyezi a vizeket a gyártásához használt festékek miatt, ezenkívül az anyag előállításához használt gyapottermés sok vizet, valamint vegyi növényvédő szert igényel.

Tekintettel arra, hogy a szűz farmer az egyik legkevésbé fenntartható szövet a piacon, az újrahasznosított farmer lehet a környezetbarát alternatíva. A posztindusztriális farmerszövet használata kiküszöbölheti a környezetszennyező előállítási folyamatokat.

A cikk eredeti verziója a Rivet 2022-es tavaszi számában jelent meg.

Fordítás, szerkesztés: Zahorján Ivett

Hablemos de Fast Fashion y Salud. Si estás leyendo este artículo quizás ya estés familiarizado con los aspectos económico, medioambientales y sociales del mundo de la moda en general, y de la Fast Fashion en particular. Pero quizás no sepas que hay una faceta más, que merece la pena considerar cuando hablamos de nuestra manera de producir y consumir textiles. Me refiero al impacto directo que los textiles pueden tener sobre nuestra salud.

En Europa se utilizan alrededor de 15.000 formulaciones químicas diferentes para textiles. Para la producción de una sola prenda se pueden llegar a utilizar hasta 40 compuestos químicos diferentes (1). Estas sustancias confieren a la prenda características que la industria nos ha vendido como necesarias. Se trata de propiedades como el antiarrugas y antimanchas, que nos permiten – según la publicidad – ahorrar tiempo y dinero. Incluso, dicen, nos podrían salvar la vida, como es el caso de las telas tratadas con retardantes de llamas, que hacen que las prendas no ardan en caso de incendio.

PERO ¿CUÁL ES EL COSTE REAL QUE ESTAMOS PAGANDO?

En números: 9,3 millones de toneladas métricas de productos químicos se utilizan en la producción mundial de textiles cada año. El 25% de todas las sustancias químicas producidas a nivel mundial se emplea en la industria de la moda (1). Las implicaciones medioambientales son ingentes. Las consecuencias para los trabajadores del sector textil son incalculables tanto en término de morbilidad como de mortalidad.

¿Y CUALES SON LAS CONSECUENCIAS PARA EL CONSUMIDOR?

Cuando esa prenda, que no arde, es impermeable, de colores vivos que resisten al sol y a los lavados, acaba en nuestros armarios, se convierte en una amenaza directa para nuestra salud. Los investigadores de la Universidad de Granada en el 2019 publicaron un estudio analizando la presencia de bisfenol-A y parabenos en textiles y la correspondiente actividad hormonal derivada de la exposición dérmica a calcetines para bebés y niños de 0 a 48 meses. Los resultados fueron contundentes: “las concentraciones de bisfenol-A son alarmemente altas y la actividad hormonal es la esperada para tales concentraciones” (2).

Estas sustancias están clasificadas como disruptores endocrinos: tienen la capacidad de alterar el equilibrio hormonal de un organismo aumentando, reduciendo o bloqueando aquellos procesos fisiológicos controlados por las hormonas. Las consecuencias de una exposición prolongada a estas sustancias sintéticas incluyen: trastornos del comportamiento, pubertad precoz, obesidad, asma y cáncer de mamas entre otros.

El problema es que este aspecto no está regulado, no hay control, ni límites que respetar (3). En las etiquetas de las prendas hay muy poca información: nos indican el tipo de fibra utilizada y el lugar en que se ha producido; pero no sabemos nada de las sustancias químicas empleadas durante el proceso de producción. ¿Compraríamos una camiseta cuya etiqueta pusiera: 20% algodón, 80% poliéster + polibromados + metales pesados + ftalatos + alquifenoles?

Aunque la legislación no nos ampare todavía, tenemos que hacer un ejercicio de responsabilidad, no solo para nosotros, sino para todos aquellos que dependen de nuestras decisiones: nuestros hijos, familiares y todos aquellos trabajadores que viven rodeados de sustancias tóxicas todos los días, para que podamos ahorrarnos de planchar un pantalón.

Como declara con tajante ironía Lucy Siegle en su libro “To die for. Is fashion wearing out the world?”: para crear un armario perfecto tenemos que tener en mente que lo que no compramos es igual de importante a lo que compramos (4). Tenemos que estar dispuestos a renunciar a algo, a perder algo, para que todos podamos ganar.

ACTÚA

Si a ti te interesa el tema, te invitamos a mirar el trailer de Detox Fashion: Moda libre de tóxicos, de Greenpeace y también a sumarte a la campaña #QuéHayEnMiRopa a través de tus redes sociales.

Referencias:

- Andrew Hudson “Aiming to zero” sgs.com, 2017.

- Freire C et al. “Concentration of bisphenol A and parabens in socks for infants and young children in Spain and their hormone-like activities”. Environmental International, 2019.

- Nicolás Oles “Libérate de los tóxicos. Guía para evitar los disruptores endocrinos. RBA, 2019.

- Lucy Siegle “To die for. Is Fast Fashion wearing out the world?” Fourth Estate, 2011.

La realidad es que la moda está cambiando y es fundamental que estos cambios tengan en cuenta la sostenibilidad y sus efectos duraderos. Globalmente consumimos alrededor de 80 mil millones de prendas nuevas cada año y muchas de ellas van al vertedero después de un período corto de uso. La moda sostenible ya no es una tendencia, sino una necesidad y comprender por qué la necesitamos es el primer paso para una revolución.

La sostenibilidad tiene en cuenta tres pilares indivisibles para garantizar que hoy podamos satisfacer nuestras necesidades sin comprometer a las generaciones futuras. Estos 3 pilares son:

SOCIAL

Para garantizar que los individuos tengan una vida bien mantenida y saludable además de que sus relaciones laborales tengan el objetivo de favorecer el desarrollo personal y colectivo.

MEDIOAMBIENTAL

Para buscar la preservación del medioambiente y reducir el daño causado por nosotros a lo largo del tiempo.

ECONÓMICO

Para aumentar el bienestar social a través de una reducción en la producción y en el consumo, con el apoyo de empresas verdes.

Equilibrar los ámbitos sociales, medioambientales y económicos es la clave para gestionar recursos en un planeta finito, garantizando bienestar social y desarrollo económico.

LA MODA Y LA SOSTENIBILIDAD

Los efectos dañinos de la acción humana ya empiezan a revelarse y la moda sostenible es una alternativa al sistema actual, que propone el uso racional de los recursos naturales, el consumo consciente que rechaza las compras por impulso y la circularidad de la producción. Además, garantiza el bienestar de los trabajadores y promueve el fin de la esclavitud moderna. Crear desde una visión holística y responsable hará que garanticemos una industria más justa para toda la cadena de producción y también para los consumidores.

Desde el punto de vista de la sociedad, estaría bien conocer mejor las marcas que nos gustan y ser curiosos sobre nuestras prendas. Por ejemplo, la campaña #QuienHizoMiRopa surgió de esta inquietud e invita a todos nosotros a preguntarnos y preguntar a las marcas quienes son los involucrados en la producción de nuestras prendas. Una acción sencilla que pone presión en las marcas para que sean más responsables con sus cadenas productivas.

Además, sería necesario disminuir nuestro ritmo de consumo y consumir con más responsabilidad, por ejemplo, preguntándonos si realmente necesitamos aquellas prendas que nos gustaría comprar en las rebajas. Buscar un equilibrio es el primer paso hacia la sostenibilidad.

SÉ CURIOSO, AVERIGUA Y ACTÚA

Desde Fashion Revolution nos proponemos ser un movimiento global de personas e instituciones que luchan por una mejor forma de producir y consumir moda, es decir, por una moda más sostenible. Amamos la moda pero sabemos que el sistema actual nos hace pagar un precio muy elevado por nuestras prendas.

Te invitamos a mirar el trailer subtitulado del documental The True Cost en nuestro canal de YouTube y a hacerte una selfie enseñando la etiqueta de una de tus prendas favoritas, con el cartel ¿Quién hizo mi ropa?

Tras una creciente demanda de recursos en un planeta finito, un aumento en la contaminación y en la explotación de los trabajadores, ha llegado el momento de la moda sostenible. Garantizando el equilibrio de los 3 pilares de la sostenibilidad: social, medioambiental y económico, garantizamos nuestro presente y futuro. ¡Súmate a esta revolución!

Today, WWF released the 2020 edition of their Living Planet Report which monitors the state of the planet – including biodiversity, ecosystems, and demand on natural resources – and what it means for humans and wildlife.

It is more urgent than ever that we tackle the global biodiversity and nature crisis. This report sounds the alarm for global biodiversity, showing globally an average 68% decline in the size of animal populations since 1970.¹ Nature is in jeopardy and we need to take urgent action!

What is biodiversity?

Simply put, biodiversity is the variety of life on Earth. Each individual of each species contributes to their local ecosystem, which in turn contributes to a wider ecosystem. Biodiversity is not just about the variety of species in an ecosystem, but also the genetic diversity which exists within each species. As species populations decline, this erodes genetic diversity, reducing the ability for a species to adapt to changes to its environment.

Why should we care?

Each ecosystem provides benefits to our planet, such as water purification, nutrient recycling, maintaining healthy soils, reducing pollution, absorbing carbon, regulation of floods and diseases, and much more. Biodiversity underpins the ecosystem, so when biodiversity is lost, we lose the ecosystems that humans rely upon to maintain our lives, such as the food we eat, the water we drink and the resources we use in our daily lives. Biodiversity is fundamental to human life on Earth and its loss will impact the health and wellbeing of people around the world, as well as deepening existing inequalities.

Humans are now overusing the Earth’s biocapacity, the ability of our planet’s ecosystems to regenerate, by at least 56%¹. This is like living off 1.56 Earths. We desperately need to rethink our global resource-intensive systems and find nature-based solutions that preserve our ecosystems, improve biodiversity and species populations and improve global health and wellbeing.

So, what are the key findings of the Living Planet Report?¹

- 68% decrease in population sizes of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles and fish between 1970 and 2016.²

- 1 million species (500,000 animals and plants and 500,000 insects) are threatened with extinction.

- Humans are now overusing the Earth’s biocapacity by at least 56%.

- The worst decline is occurring in the tropical subregions of the Americas where we are seeing an average of 94% decline in population sizes.²

What is causing this catastrophic loss?

Whilst this varies in different regions of the world, The Living Planet Report states the biggest threats to biodiversity are:

- Changes in land and sea use (unsustainable agriculture, logging, transportation, urbanisation, energy production and mining) (43%-58%)³

- Species overexploitation (unsustainable hunting and poaching, fishing or harvesting) (18%-36%)³

- Invasive species and disease (11%-14%)³

- Pollution (oil spills, agricultural run-off, air pollution or water pollution) (2%-11%)³

- Climate Change (4%-13%)³

What’s the fashion industry’s role in this?

The fashion industry relies heavily on biodiversity, predominantly through the production and processing of all the different materials used to make our clothes, as well as the materials used for packaging. The fashion industry has a significant damaging impact on biodiversity, throughout the production process as well as during wear, care and disposal.

Changing land use

A large proportion of fashion’s biodiversity impact occurs due to habitat change resulting from agriculture for producing cotton, viscose, wool, rubber, leather hides or any other natural fibre. For example, fashion is a significant contributor to global deforestation with around 150 million trees logged every year to be turned into cellulosic fabrics, such as viscose. ⁵ In the Amazon, cattle ranching is the largest driver of deforestation. Between 2006 and 2010, beef accounted for around two-thirds of the export value of Brazilian cattle products, whilst leather was responsible for over one-quarter of the export value.⁶

The impacts of raw materials on nature will only increase as global demand for clothing increases. The fashion industry is projected to use 35% more land for fibre production by 2030 – an extra 115 million hectares that could be left to preserve biodiversity.⁴

Pollution

Whilst the full extent of fashion’s pollution impact is unknown, estimates have previously suggested that 20% of global freshwater pollution comes from the wet processing of the textile industry.⁷ Wet processing includes the scouring, bleaching, dyeing, printing and finishing of raw textiles which are water and chemical intensive processes.

Although many companies are cleaning up their acts and investing in cleaner dyeing innovations and better wastewater treatment, many of the world’s waterways are still being polluted. The Citarum River in Indonesia is home to around 2,000 textile factories where effluent from the dyeing and processing of fabrics has previously been dumped, with little or no regulation. This has caused extensive environmental and human health issues in the area.

Additionally, pesticides used for the production of our raw materials have been shown to reduce the populations of important species, whilst also eroding soil biodiversity. Although the cultivated area of cotton covers only 3% of the planet’s agricultural land, it uses 16% of all insecticides and 7% of all pesticides.⁸ Some have been banned and replaced, but many insecticides continue to kill or harm a broad spectrum of insects, including those that pollinate crops. ⁸

Climate Change

From raw material to disposal, the entire lifecycle of our clothing impacts our climate. It has been estimated that the fashion industry emitted around 2.1 billion tonnes of GHG emissions in 2018, equating to 4% of the global total. ⁹ Overall 52% of fashion’s GHG emissions come from raw material production and fabric and yarn preparation.⁹ This is driven by fashion’s obsession for synthetic oil-based materials such as polyester, which account for around 60% of the clothes we produce.¹⁰

We know that even just a small increase in global temperatures will have a devastating affect on nature. Fashion needs to wake up and take steps to decarbonise and move towards carbon neutrality.

What can the fashion industry do?

Globally, patterns of overproduction and consumption are indirect drivers of biodiversity loss as they underlie land-use change and habitat loss, the overexploitation of natural resources, pollution and climate change which are the drivers of biodiversity loss. We need to rethink current clothing consumption models and buy less, buy better, wear our clothes longer and figure out how to successfully recycle them in a circular manner.

In term’s of fashion’s impact on land, we need to be looking at regenerative agriculture which aims to rehabilitate and enhance the natural ecosystems. Currently , farmers producing fibres used by Patagonia, Eileen Fisher, Burberry and Kering Group (who owns Gucci, Saint Laurent and other major brands) are beginning to use regenerative farming methods in order to improve biodiversity and capture carbon, helping to lower CO2 levels. This method is now being used to produce raw materials used for fashion such as hemp, flax, bamboo and cotton and to raise cattle, goats and sheep.

Facing a climate emergency, fashion brands must also focus their recovery on breaking away from fossil fuels in their supply chain. A recent report by Stand.Earth outlines the steps fashion brands must take to reduce their emissions rapidly, including setting ambitious climate commitments with full transparency, focussing on renewable energy in supply chains, sourcing lower carbon and longer lasting materials, and reducing the climate impacts of shipping.¹¹

Whilst we all have a role to play to help nature recover locally and globally, businesses and policymakers need to take drastic action to ensure that nature is protected and restored. We still have a chance to put things right but we need change fast – we need it now.

Finally, the best way to motivate industry and governments to take action is by using your voice to demand action. This year we launched #WhatsInMyClothes? with the aim to encourage brands to tell us more about the materials, chemicals and environmental impacts of the clothes we wear. We deserve to know if our clothing is contributing to biodiversity loss or environmental degradation, so use your voice and ask your favourite brands #WhatsInMyClothes?

References

- WWF, Living Planet Report, 2020, https://livingplanet.panda.org/en-gb/

- This is the average decline in population sizes between 1970 and 2016, to calculate this, the Living Planet Index tracks the abundance of almost 21,000 populations of mammals, birds, fish, reptiles and amphibians around the world.

- The proportion of threats which vary regionally. For more information please see pages 18 – 21 in the Living Planet Report.

- Boger S. et al., Pulse of the Fashion Industry. Global Fashion Agenda, 2017, http://globalfashionagenda.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Pulse-of-the-Fashion-Industry_2017.pdf

- Canopy, CANOPY STYLE 5-YEAR ANNIVERSARY REPORT, 2018, https://canopyplanet.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/CanopyStyle-5th-Anniversary-Report.pdf

- Walker et al., From Amazon Pasture to the High Street: Deforestation and the Brazilian Cattle Product Supply Chain, Tropical Conservation Science, 2013 http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/194008291300600309

- Maxwell, McAndrew and Ryan, The state of the apparel sector: water, 2015, https://www.textilepact.net/pdf/publications/reports-and-award/glasa_2015_stateofapparelsector_specialreport_water.pdf

- Pesticide Action Network UK, Is cotton conquering its chemical addiction?, 2017, http://www.pan-uk.org/cottons-chemical-addiction/

- McKinsey and the Global Fashion Agenda, Fashion on Climate, 2020, https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Retail/Our%20Insights/Fashion%20on%20climate/Fashion-on-climate-Full-report.pdf

- Kirchain et al., Sustainable Apparel Materials, 2015 https://matteroftrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/SustainableApparelMaterials.pdf

- Stand.Earth, FASHION FORWARD: A Roadmap to Fossil Free Fashion, 2020, https://www.stand.earth/sites/stand/files/standearth-fashionforward-roadmaptofossilfreefashion.pdf

Written by Sienna Somers, Global Policy and Research Coordinator.

Covid-19 was not going to come in the way of Fashion Open Studio 2020 and its audience. If anything, the pandemic gave this year’s designers a greater audience than ever. The studio tours, workshops and conversations were pivoted to a digital format, allowing us to #StayHome while also staying connected with the creative community making use of this time to rethink systems, supply chains and resources.

Sustainability means many things

We celebrated the work of 53 designers across 14 countries including Iran, New Zealand, Vietnam, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Switzerland and Germany. There was so much to learn from the designers who took part, each one with solutions to the challenges most pressing to them. At Fashion Open Studio we understand that sustainability means many things (and sometimes, nothing at all). Every designer taking part in this programme is finding solutions that will help to move their own business forward without over stretching the planet’s resources and with respect for artisans and garment workers who craft and stitch their collections. The purpose of Fashion Open Studio is to share these stories and help them to reach the audiences they deserve.

From Fashion Revolution’s incredible global network there were so many eloquent voices, with as many different perspectives on how clothing should be made and valued. From Zimbabwe, Fashion Revolution’s country coordinator Rudo Nondo talked to Julian Tamuka about his brand Guyllelujah. Julian had previously not considered ideas about sustainability until he was introduced to Fashion Revolution through Fashion Open Studio and realised his use of limited resources – deadstock materials and off cuts – and his philosophy of making staple items of clothing because as he says “it’s a staple for a reason, it’s more likely to be of value and stick around longer,” is the way he works out of necessity.

I recommend everyone watches his short video, The New Philosophy of Fashion as there is so much to learn from his approach.

Likewise, from Harare, Haus of Stone presented Therapy of Fashion, which combined mediation and making one session of mindfulness and creativity. The brand’s founder, Danayi, led us through a fusion of yoga; traditional mbira music and hand sewing. Participants are invited to send the roses they make in the workshop to become part of a collective scarf called ‘Hope’.

View this post on Instagram

In Switzerland in collaboration with Mode Suisse, Rafael Kouto asked “What is Upcycling? And what is waste?” Rafael showed how to ‘pimp’ your garments with an introduction on his upcycling practice and so much information and advice on rethinking and valuing the contents of your own wardrobe. It’s a really wonderful and informative session.

From Pune in India, Karishma Shahani Khan invited small groups into a virtual studio each day to learn quilting, embroidery and hand sewing techniques in a series of sewing circles with the team from Ka Sha and the artisans they work with. They wanted to share the inherent social setting of storytelling and conversations that they witness within their everyday working environment with guests.

Also in India, in Jaipura in Rajasthan, Iro-Iro showed their practice around implementing zero-waste for their MoonWash collection, focusing on New Heroes with illustrations and readings celebrating women throughout history who have been independent thinkers and doers.

If you missed these remarkable stories, they are still available as a series of readings of letters to women from Cleopatra to the spy princess Noor Inayat Khan, and there is a collection of clothes inspired by each of them.

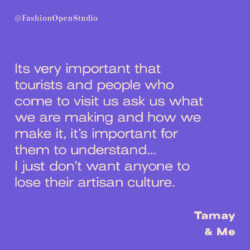

Vietnamese brand Tamay & Me introduced Mien artisan and co-founder Tamay from Ta Phin village in Sapa,

with a special film screening followed by a Q&A with her co-founder Hannah Cowie to explain how they work together and the heritage of the unique craftsmanship that goes into every garment.

Creativity in lockdown thrived

While the world was in lockdown, many designers still had access to their studios, either because they live in the same space, or because they were using them to continue working at a safe social distance in the essential work of making PPE and hospital scrubs as many of the Fashion Open Studio network were doing. Phoebe English talked to us from her Deptford Creek studio in south London, explaining how to quilt with waste using her paper templates.

As she spoke, the scrubs she had been making were being counted and packed up ready to be delivered to hospitals in need as part of the Emergency Designer Network with fellow FOS designer Bethany Williams. Elliss Solomon, founder of Elliss, took time out from her work for Scrub Up for the NHS to talk us through her workshop on collage – a key part of her creative development when she is designing a collection. Many others taking part in the week were playing their part in making masks, scrubs and PPE and of course, the week’s events were a great way for people to spread the word, stay connected, and share the challenges of trying to keep business going.

Collaboration makes sense

While there are designers who are still fledgling brands, this is a particularly difficult time for those newly graduated. Among the thousands of fashion graduates unable to even show their final collections as part of a degree show, we showcased the work of two emerging talents who had shown their collections as part of the Central Saint Martins MA show in March, just a week before the lockdown. The portfolio visits traditionally held for industry experts to head hunt talent, were cancelled, with future job prospects on hold for many. Matthew Needham, who temporarily joined the Fashion Revolution team for the week to help on production and Zoom management, talked us through his final collection ØYEBLIKK / 2020 ‘IN THE BLINK OF AN EYE’.

View this post on Instagram

While Needham is an advocate of waste management – a master of using trash as a precious resource in his collections – he is also becoming expert in collaboration, and is sure that this is the way forward. For his session, he brought together his co-collaborators Sneaker artist Helen Kirkum, Biotech materials researcher Alice Potts and experimental milliner Jo Miller. Together they explained some of their processes and how working collectively is a great way to consolidate sustainable thinking, encourage innovation and help lift each other’s practice and find new audiences.

Somerset House x Young Creatives

Fellow CSM MA graduate Paolo Carzana moved back to his hometown in Cardiff, Wales, the week he was supposed to be showing his final collection to the world. Paolo was chosen as the finale to the degree show, with The Boy Who Came Back to Life, a collection packed with details, extraordinary materials, botanical dyes, Pinatex textiles, and layers of story-telling, autobiographical notes, and months’ worth of research.

For his session which was part of the afternoon of events in partnership with Somerset House and its Young Creatives programme, Carzana talked from the balcony of his flat overlooking the Cardiff stadium which was at the time, being turned into a Nightingale hospital. He had made a special film, A Self Isolation Waltz for the event showing his collection against the backdrop of the building site below, and talked through his sketches, fabric swatches and references. He also talked about his plans to make a capsule collection for the planned digital London Fashion Week in June, re-using pieces from his previous work. The pandemic has forced him to rethink how he is going to work and sell – and be even more resourceful creative and sustainable as a business going forward.

Also taking part in the Somerset House programme were Bethany Williams, Katie Jones and Congregation Design. Bethany was part of a week-long series of events to celebrate the anniversary of Earth Day, planned with Somerset House long before the pandemic took hold. You can watch highlights of the day here.

There is so much to learn from the 2020 Fashion Open Studio designers. We are still absorbing and catching up with so many incredible and diverse sessions. The digital programme allowed these small, intimate studio conversations and workshops to be viewed by a global audience creating conversations that reverberated between designers and communities that hadn’t previously connected.

We are starting to plan for Fashion Open Studio 2021 and will be announcing how to apply to take part in the coming months. Until then, do spend some time watching the videos on our YouTube playlist and share the knowledge and the work of these change maker designers far and wide.

To stay up to date with Fashion Open Studio, subscribe to the Fashion Revolution youtube channel and follow Fashion Open Studio on instagram, twitter and facebook.

During the month of February, we’ve been exploring fashion’s impact on water and looking at how we can practice water stewardship through our wardrobes. So far, we’ve discussed the consequences of industrial dyes, misconceptions around water consumption, and better laundry habits to conserve water. Now, we’re taking a look at how our wardrobes affect our oceans when they release microfibres.

What are microfibres?

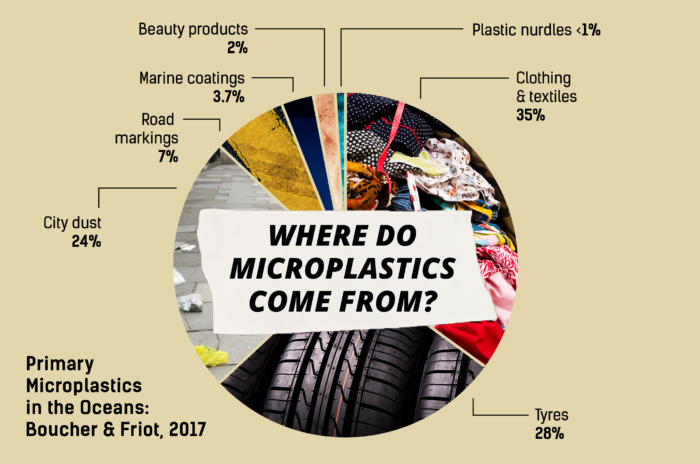

Microplastics are tiny plastic pieces that are less than <5 mm in length. Textiles are the largest source of primary microplastics (specifically manufactured to be smaller than 5mm), accounting for 34.8% of global microplastic pollution [1]. Microfibres are a type of microplastic released when we wash synthetic clothing – clothing made from plastic such as polyester and acrylic. These fibres detach from our clothes during washing and go into the wastewater. The wastewater then goes to sewage treatment facilities. As the fibres are so small, many pass through filtration processes and make their way into our rivers and seas.

Around 50% of our clothing is made from plastic [2] and up to 700,000 fibres can come off our synthetic clothes in a typical wash [3]. As a result, if the fashion industry continues as it is, between the years 2015 and 2050, 22 million tonnes of microfibres will enter our oceans [4].

What impact do microfibres have on the environment and on human health?

Due to the tiny size of microplastics, they can be ingested by marine animals which can have catastrophic effects on the species and the entire marine ecosystem.

Microfibres can absorb chemicals present in the water or sewage sludge, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and carcinogenic Persistent Organic Pollutants (PoPs). They can also contain chemical additives, from the manufacturing phase of the materials, such as plasticisers (a substance added to improve plasticity and flexibility of a material), flame retardants and antimicrobial agents (a chemical that kills or stops the growth of microorganisms like bacteria). These chemicals can leach from the plastic into the oceans or even go straight into the bloodstream of animals that ingest the microfibres. Once ingested, microfibres can cause gut blockage, physical injury, changes to oxygen levels in cells in the body, altered feeding behaviour and reduced energy levels, which impacts growth and reproduction [5][6]. Due to this, the balance of whole ecosystems can be affected, with the impacts travelling up the food chain and sometimes making their way into the food we eat! It has been suggested that people that eat European bivalves (such as mussels, clams and oysters) can ingest over 11,000 microplastic particles per year [7].

What can fashion brands do?

The fashion industry needs to take responsibility for minimising future microfibre releases. Brands can have the most impact if they take microfibre release into consideration at the design and manufacturing stages. Designers should consider several criteria in order to minimise the environmental impact of a synthetic garment [3]:

- Use textiles which have been tested to ensure minimal release of synthetic microfibres into the environment.

- Ensure the product is durable so it remains out of landfill as long as possible

- Consider how the garment and textile waste could be recycled, to achieve a circular system.

During manufacture, there are several methods that can be applied to reduce microfibre shedding such as brushing the material, using laser and ultrasound cutting [4], coatings and pre-washing garments [1]. The length of the yarn, type of weave, and method for finishing seams may all be factors affecting shedding rates. However, much more research from brands needs to occur in order to determine best practices in reducing microfibres and create industry-wide solutions.

Waste-water treatment…

Waste-water treatment plants (where all our used water gets filtered and treated) are currently between 65-90% efficient at filtering microfibres [6]. Research and innovations into improving the efficiency of capturing microfibres in wastewater treatment plants is essential to prevent them escaping into our environment.

Washing machine filters…

Improving and developing commercial washing machine filters that can capture microfibres may allow for an additional level of filtration, whilst also educating consumers and businesses [8]. However, current filters which need to be fitted by the user, such as that developed by Wexco, are currently expensive and reportedly difficult to install. They also place a financial burden upon the consumers, rather than pressurising brands to commit to change. To tackle this, we need more industry research and legislation to ensure all new washing machines are fitted with effective filters to capture the maximum amount of microfibres possible. However, we then have the issue of what to do with the microfibres once we have caught them – an area which requires more research and industry collaboration.

Collaboration is key

Collaboration across multiple industries is required if we are to tackle microfibre pollution. In addition to material research, waste management and washing machine research and development, there is a role for other sectors such as detergent manufacturers and the recycling industry to come together to help reduce microfibre pollution. Cross-industrial agreements could help promote collaboration between industry bodies and promote sharing of resources and knowledge.

A major issue has been a lack of a standardised measure of measuring microfibre release. However, a cross-industry group, The Microfibre Consortium recently announced the first microfibre test method. The launch will enable its members (including brands, detergent manufacturers and research bodies) to accelerate research that leads to product development change and a reduction in microfibre shedding in the fashion, sport, outdoor and home textiles industries. The Microfibre Consortium also works to develop practical solutions for the textile industry to minimise microfibre release to the environment from textile manufacturing and product life cycles.

The need for microfibre legislation

Comprehensive legislative action is needed to send a strong message and force the brands to address microfibre releases from their textiles. This is a complicated issue that will require policymakers to tackle this issue on many different levels and sectors. Currently, there are no EU regulations that address microfibre release by textiles, nor are they included in the Water Framework Directive.

However, there have been several developments in microfibre legislation in the past few years:

- As of February 2020, Brune Poirson, French Secretary of State for the Ecological and Inclusive Transition, is the first politician in the world to pass microfibre legislation. As of January 2025, all new washing machines in France will have to include a filter to stop synthetic clothes from polluting our waterways. This makes France the first country in the world to take legislative steps in the fight against plastic microfibre pollution. The measure is included in the anti-waste law for a circular economy.

- In 2018, US states of California and Connecticut proposed legislation which would see polyester garments legally required to bear warning labels regarding their potential to shed microfibres during domestic washing cycles. However, this legislation is yet to be passed.

- In 2019, the EAC urged the UK government to accelerate research into the relative environmental performance of different materials, particularly with respect to measures to reduce microfibre pollution, as part of an Extended Producer Responsibility scheme. However, the UK government rejected the proposal stating that current voluntary measures are sufficient.

What can you do?

Write to your policymaker

It is vital that policy is put into place to tackle microfibres, such as the new French washing machine filter legislation. If you are concerned about microfibres, we encourage you to write to your policy representative and urge your government to take action on microfibre pollution. Now that France has enacted the microfibre legislation, it raises the bar for other governments to also take action, but they will only do so with enough pressure from the people they represent – you!

Changing your washing practices

The easiest thing you can do to minimise microfibres releasing from your clothing is to simply wash your clothes less. Given that up to 700,000 microfibres can detach in a single wash [3] ask yourself if that item really needs to be washed or can it be worn once or twice more before you do?

While some research suggested using a liquid detergent, lower washing machine temperatures, gentler washing machine settings [3] and using a front-loading washing machine [9] can reduce microfibre shedding. Researcher Imogen Napper stated they found that there was no clear evidence suggesting that changing the washing conditions gave any meaningful effect in reducing microfibre release.

You can also use a Cora Ball, a guppy bag or a self-installed washing machine filter to capture microfibres from your clothing. The CoraBall and Lint LUV-R (an install yourself washing machine filter) have been shown to reduce the number of microfibres in wastewater by an average of 26% and 87%, respectively [10]. Although these can’t solve the problem, we still want to divert as many microplastics as we can from entering our waterways.

Should we all switch from synthetic fibres?

While many people’s first instinct is to switch from synthetic materials to natural materials to minimise microfibre release, this is not always a simple choice as there are other sustainability aspects involved. The UK’s Environmental Audit Committee in their report states ‘A kneejerk switch from synthetic to natural fibres in response to the problem of ocean microfibre pollution would result in greater pressures on land and water use – given current consumption rates’ [11].

Demand brands to do more to take action on microfibres

“Ultimate responsibility for stopping this pollution, however, must lie with the companies making the products that are shedding the fibres.” states the Environmental Audit Committee [11], but there are still too many major fashion brands not taking responsibility for what happens in their supply chains and in the life cycle of their products. As well as demanding action from your policymaker, we should also ask brands what they are doing to minimize the microfibre release from their products. It is clear that there is still a lot of work to do, and as their customers, we have a lot of power in influencing the impacts of the brands we buy.

The impacts of microfibres on the environment can be mitigated, but only with systematic and meaningful change supported by policymakers, brands, industry, NGOs and citizens all working together.

References

[1] Boucher, J. and Friot, D. (2017). Primary Microplastics in the Oceans: A Global Evaluation of Sources. IUCN. Available at: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2017-002-En.pdf

[2] Textile Exchange (2019). Preferred Fiber and Material Market Report. Available at: https://store.textileexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/woocommerce_uploads/2019/11/Textile-Exchange_Preferred-Fiber-Material-Market-Report_2019.pdf

[3] Napper, I. and Thompson, R. (2016). Release of synthetic microplastic plastic fibres from domestic washing machines: Effects of fabric type and washing conditions. Marine Pollution Bulletin. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X16307639?via%3Dihub

[4] Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2017). A new textiles economy: Redesigning fashion’s future. Available at: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/A-New-Textiles-Economy_Full-Report_Updated_1-12-17.pdf

[5] Koelmans, A., Bakir, A., Burton, G. and Janssen, C. (2016). Microplastic as a Vector for Chemicals in the Aquatic Environment: Critical Review and Model-Supported Reinterpretation of Empirical Studies. Environmental Science & Technology. Available at: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.est.5b06069

[6] Henry, B., Laitala, K. and Grimstad Klepp, I. (2018). Microplastic pollution from textiles: A literature review. Consumption Research Norway SIFO. Available at: https://www.hioa.no/eng/About-HiOA/Centre-for-Welfare-and-Labour-Research/SIFO/Publications-from-SIFO/Microplastic-pollution-from-textiles-A-literature-review

[7] Van Cauwenberghe, L. and Janssen, C. (2014). Microplastics in bivalves cultured for human consumption. Environmental Pollution. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0269749114002425

[8] Browne, M., Crump, P., Niven, S., Teuten, E., Tonkin, A., Galloway, T. and Thompson, R. (2011). Accumulation of Microplastic on Shorelines Worldwide: Sources and Sinks. Environmental Science & Technology. Available at: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es201811s

[9] Hartline, N., Bruce, N., Karba, S., Ruff, E., Sonar, S. and Holden, P. (2016). Microfiber Masses Recovered from Conventional Machine Washing of New or Aged Garments. Environmental Science & Technology. Available at: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.est.6b03045

[10] McIlwraith, H., Lin, J., Erdle, L., Mallos, N., Diamond, M. and Rochman, C. (2019). Capturing microfibers – marketed technologies reduce microfiber emissions from washing machines. Marine Pollution Bulletin. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.12.012

[11] Environmental Audit Committee (2019). Fixing Fashion: clothing consumption and sustainability. House of Commons. Available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmenvaud/1952/1952.pdf

Research and writing by Sienna Somers, Policy and Research Co-ordinator at Fashion Revolution

Tomorrowland: how innovation and sustainability will change the fashion panorama.

On Wednesday, 24th April 2019, Fashion Revolution hosted our fifth annual Fashion Question Time, a powerful platform to debate the future of the fashion industry during Fashion Revolution Week. This year Fashion Question Time was hosted for the first time at the V&A museum and opening the event up to the public for the first time. The theme this year was Tomorrowland: how innovation and sustainability will change the fashion panorama.

Chaired by Baroness Lola Young of Hornsey, this year’s panel brought together leading figures across government and the fashion industry to discuss the future of the fashion industry.

Attendees included high-level fashion industry representatives from across the sector, global brands, retailers, press, MPs, influencers, and NGOs. Panelists included Mary Creagh, MP and Chair of the Environmental Audit Committee; Laura Balmond, Project Manager, Ellen MacArthur Foundation; Mark Sumner, Lecturer in Sustainability, Fashion & Retail, University of Leeds, and Hendrik Alpen, Sustainability Engagement Manager, H&M Group.

After a welcoming speech from Tim Peeve, an opening speech was made by Sarah Ditty, Policy Director for Fashion Revolution:

“There is an ocean of truth lying undiscovered before us when it comes to the fashion industry of tomorrow. We urgently need to focus on innovation and we need sustainability to be scaled up.”

Below we have selected some questions and answers that were discussed over the 1 hour ½ debate during Fashion Question Time 2019 at the V&A:

Olivia Shaw, Campaign Support Officer for #LoveNotLand

fill and London Waste & Recycling Board asked:

“In a world with finite resources, why does the fashion industry waste around three quarters of what it creates and how are we going change this model to create a fair system for all?”

Laura Balmond, Project Manager, Ellen MacArthur Foundation: It’s not possible to continue as we go on… The amount of clothes produced is rapidly increasing – and we are using clothes 40% less. Less than 1% of materials are going back into fashion we make… We need a huge systemic rethink .. I believe that the circular economy will be business-led. We need businesses to get behind this common vision… The current system doesn’t work. The leaders will continue to push ahead – will the others exist in 5 years time?

Mark Sumner, Lecturer in Sustainability, Fashion & Retail, University of Leeds: Technically there are lots of solutions but there’s no motivation… We have the opportunity to change this and legislation plays an important role. The fashion industry has been around for thousands of years. It plays an important role in self-esteem and identity, plays an important part in our lives. But we can’t stick with the model we have at the moment, we need to change. The Modern Slavery Bill is a good starting point but we need more legislation. More innovative structures in place to penalise businesses – the responsibility needs to be across the whole system.

Mary Creagh, MP and Chair of the Environmental Audit Committee: The current fashion industry model promotes over consumption and under utilisation. My concern is that the policy space in this country, which has historically been a leader on these issues, has been crowded out by the Brexit psychodrama and the space for creative and necessary responses to this is being handed to us. We’re in a unique situation where the public is dragging the Government. We debated the environment twice in Parliament twice yesterday so things are changing but we all need to think about our overconsumption… We also need to strengthen regulation to require greater executive level accountability for tackling modern slavery and reducing greenhouse gas emissions in business and supply chains.

Hendrik Alpen, Sustainability Engagement Manager, H&M Group: Moving to a circular model makes business sense. Right now, H&M operates one of the biggest global take-back schemes.

Sarah Ditty, Fashion Revolution, Policy Director on behalf of Labour behind the Label asked:

The one safety initiative that came out of the Rana Plaza collapse, the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, is at risk of being expelled from the country at the moment, putting all the progress made in the last six years at risk. At the moment over 50% of the factories still lack adequate fire alarm and detection systems and 40% are still completing structural renovations, these life-saving remediations need to be overseen by the Accord. With the Accord under threat, how can innovations in transparency create a better future for garment workers?

Laura Balmond, Project Manager, Ellen MacArthur Foundation: With innovations around transparency, relies purely on the information that is inputted at the very beginning. So, this then raises the question of how do we verify that and how do we ensure the information you are receiving is correct? Therefore, what are the financial incentives to improve the system? We must incentivise accurate data inputting.

Hendrik Alpen, Sustainability Engagement Manager, H&M Group: The Accord is a very well working mechanism. So, we as a brand, and other brands hope it will continue. Last year 98% of our suppliers were compliant with the Accord’s requirements, and this year, it will be 100% compliance. You talk about incentives, so that’s a sort of incentive we can create to get something back for the work we are investing, besides, you know, it’s the right thing to do. This can also create a level playing field between brands and this is very crucial to make informed choices.

Mary Creagh, MP and Chair of the Environmental Audit Committee:

The real costs of what goes into those clothes are not truly priced. We will only have change if we price clothing based on the material, the labour, and carbon emissions. Those costs are currently passed onto the countries of production… Currently, it’s down to little NGOs to police big brands. Footlocker doesn’t provide an anti-slavery statement on their website, for example… We must make accountants and CEOs accountable for slavery and emissions. Anyone with a pension fund can buy shares in a business, and as a shareholder, you can go to AGMs and to put pressure on these brands.

Sara Arnold of Extinction Rebellion asked:

To have a chance of avoiding the worst effects of the climate and ecological collapse, we must get to net zero carbon by 2025 and halt the loss of biodiversity. The mobilisation we need is unprecedented and as an industry, we should be declaring climate and ecological emergency and acting as so. If this was treated as the emergency that it is, would there be any place for fast fashion? Would there be a place for fashion at all?

Hendrik Alpen, Sustainability Engagement Manager, H&M Group: Obviously, it is hard to say we shouldn’t exist! But I can relate to the thoughts. So, our job is to reduce the impact of what we do. So that’s why we set the goal to be climate positive by 2040, that may be too late, but we are discussing timelines. We have made changes across our stores, and office to be powered by renewable electricity. So, the challenge we have is how do we bring that into the supply chain? And our first goal is to have a climate neutral supply chain by 2030. That’s a huge challenge, we don’t know how to do that, but that’s the challenge we are taking on and we have to take on. Then the question is how can we continue to operate with such a business model which still brings fashion to the people but how do we do that in a better way? Our business model is based on selling products and it still will be for a while and on the other hand, that means jobs for people, joy for people but we need to find a different way.

Laura Balmond, Project Manager, Ellen MacArthur Foundation:

Think of the global population, what do people want, what do people need. Firstly, we need clothes, but then we have a prospect of fashion. Fashion is creative and meets a variety of needs of the people. So you’ve got on the one hand, Instagram bloggers who wear many different outfits and that’s how they’ve learnt to operate. And that’s okay, we don’t want to stifle creativity or fun. At the opposite end of the spectrum, you’ve got the guy that’s had his pair of Levi’s and loves them and doesn’t want them to ever wear out and he’s set for life. So how can the fashion industry rise to the challenge of meeting both these needs and still continue to exist? This can lead to interesting things coming out of this, for instance, an organisation that curates a digital wardrobe, so why do they necessarily need to own clothes at all…This is the end where rental models, swapping will be the way to keep clothes in use for as long as possible, just not with the same person. Then, on the other hand, we need to create well made, durable and repairable clothing. And that’s the challenge for the fashion industry: how can it rise to better meet the needs of the consumers?

Mark Sumner, Lecturer in Sustainability, Fashion & Retail, University of Leeds:

We’ve got 11 years to solve climate change, and I suspect it’s going to be less than that. So I agree, that it’s not fast enough. But I think you need to understand that its systemic part of culture and the part that the fashion industry plays in it. Fashion plays a really important role in our lives, for self-esteem, identity, it’s about projecting our position in society. It a really important part of our lives… I think it’s really interesting when people talk about fast and slow fashion, I go around fabric mills and garment factories, you can see excellent best practice happening in fast fashion supply chain and at the same time, around the corner you see absolutely diabolical conditions in factories supplying to luxury brands, sometimes run by the mafia. So, to think that luxury, fast fashion and slow fashion are different concepts is false. I think what we need to be looking at is brands and retailers that are doing good things, H&M, for example, are trying lots of different models, they haven’t got the answers yet but at least they are trying. Some brands out there don’t even know they have to ask the question about climate change, it’s not on their agenda at all. Those organisations are the ones we really need to metaphorically give them a kick. Different business models need to be developed but that does require significant change, so it’s also about changing the way we behave.

Mary Creagh, MP and Chair of the Environmental Audit Committee:

Thank you [to Extinction Rebellion] for creating the operating space for MP’s like me, who have always been a bit of a lonely voice, to become normalised.

But also, while there is a climate emergency, there’s also a social emergency on hand. And we need to tackle both of these things together. And switching to a low-carbon economy, we have to make it adjust transitionally, we have to make sure we don’t create winners and losers, so that fashion shouldn’t just become something for rich people to enjoy. So, when we look at how we are going to transition, we have got problems with our transport, in agriculture and the way we fuel our homes. So those are the three policy challenges for government. Had we moved from our over-consuming society very quickly, we aren’t going to get to net zero by 2025. The science will tell us what to do to get to net zero by 2050, and then in five years’ time to 2040 and then we’ll aim to get there for 2035. We have wasted the last 10 years, we’ve had no new policy in this country to change behaviour and we’ve done some policy mistakes along the way. I think fashion needs to set out it’s roadmap to net zero. It needs to say how we get to net zero and the target needs to be legally enforceable and not just voluntary.

Dr Mark Sumner, Lecturer in Sustainability, Fashion & Retail, University of Leeds:

This isn’t just about fashion, it’s a culture of consumption. There are brands doing good stuff who are being lambasted by the press and the ones that aren’t doing anything are slipping into the shadows.

Closing Fashion Question Time 2019, Orsola de Castro, co-founder of Fashion Revolution, made a powerful closing speech:

“There is absolutely no excuse anymore. We all have to do what is required of us as people, people working in companies, in governments, in education, in the media, and at home. We have to fight the system and we have to fight our lifestyle. We can’t do this without information and we can’t access verifiable, comparable and understandable information without transparency and public disclosure… We have to move from a culture of exploitation to one of appreciation and place respect for resources and for each other before every deed and every process.”

The other questions asked were:

Antonio Roade, Senior CSR Manager, New Look asked:

Technology will be vital to transition towards a circular economy; and we keep on seeing big companies investing millions collaborating with different research institutions; in different areas and often with no clear outputs. How do we coordinate different initiatives and who should be taking the lead on this (research institutions, governments or brands)?

Elle L, Artist, Expert Advisor in Fashion and Media to United Nations Environment Programme asked:

As we know, fast fashion uses a lot of synthetics which we in the room and the government now know to be highly toxic and damaging to the environment — do you think that a tax can and should be implemented to minimise or how do we phase out the amount of synthetics produced?

Julie Hill, Chair of WRAP asked:

What are the best tools to drive resource efficiency and transparency in the fashion supply chain?

Jennifer Eweh, Designer and Entrepreneur, Eden Diodati asked:

What are the opportunities and challenges involved with automation, blockchain, and artificial intelligence being used within the fashion supply chain?

Siobhan Wilson, Owner, The Fair Shop asked:

Small business and organisations have been driving change in communities across the country and beyond in making, repairing, reinventing and reusing. How can these businesses be nurtured and supported more here in the UK, so they can flourish at a greater scale and gain further exposure to a mainstream fashion audience?

Jasmine Hemsley, Cook, Author and wellness expert, asked:

What will our future look like without sustainable fashion being commonplace?

A very special thank you to the Edwina Ehrman for opening the V&A to Fashion Revolution’s Fashion Question Time and to the rest of the V&A team for your efforts in making this event a success. And a thank you to Sienna Somers and the rest of the Fashion Revolution team for organising this event.

All images Copyright Rachel Manns / www.rachelmanns.com / @rachel_manns / Rachel Manns is an internationally commissioned freelance photographer based in London, UK. She has spent the last decade shooting for a range of clients all over the world. She has a strong passion for sustainability and human rights. With fierce ethical values and a beautiful visual style, Rachel’s work perfectly intertwines the two. Her aim is to use her camera to aid positive change globally, whether that’s politically or commercially, whilst never compromising on aesthetic. Get in contact for rates.

WHY SHOULD BRANDS PUBLISH SUPPLIER LISTS?

Publicly disclosed supplier lists are helping trade unions and workers rights organisations to address and fix problems which workers are facing in the factories that supply major brands and retailers. This sort of transparency makes it easier for the relevant parties to understand what went wrong, who is responsible and how to fix it. It also helps consumers better understand #whomademyclothes.

“Knowing the names of major buyers from factories gives workers and their unions a stronger leverage, crucial for a timely solution when resolving conflicts, whether it be refusal to recognise the union, or unlawful sackings for demanding their rights. It also provides the possibility to create a link from the worker back to the customer and possibly media to bring attention to their issues.” says Jenny Holdcroft, the Assistant General Secretary of IndustriALL Global Union

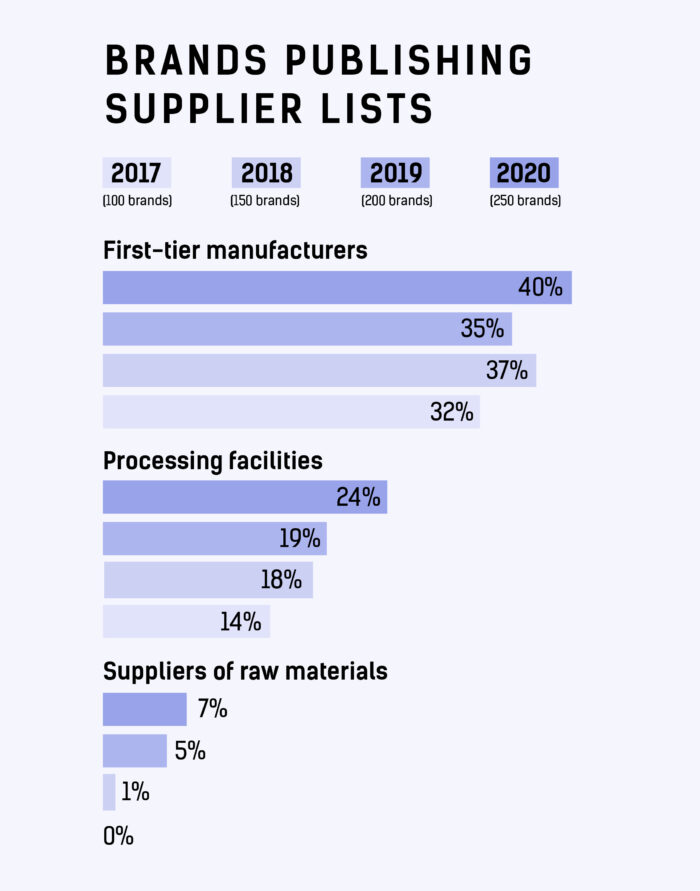

HAVE WE SEEN AN INCREASE IN BRANDS PUBLISHING SUPPLIER LISTS?

Since we began the Fashion Transparency Index in 2016, we have seen a significant increase in the number of brands publishing their first tier, processing and raw materials suppliers. In our 2020 edition of the Fashion Transparency Index, 101 out of 250 brands (40%) are publishing their first-tier manufacturers, up from 35% in 2019. These are the facilities that do the cutting, sewing and finishing of garments in the final stages of production.

60 out of 250 brands (24%) are publishing some of their processing facilities, up from 19% in 2019. These are the sorts of facilities that do ginning and spinning of yarn, knitting and weaving of fabrics, dyeing and wet processing, leather tanneries, embroidering and embellishing, fabric finishing, dyeing and printing and laundering.

And, 18 out of 250 brands (7%) are publishing some of their raw material suppliers, up from 5% in 2019. These suppliers are those that provide brands and their manufacturers further down the chain with raw materials such as cotton, wool, viscose, hides, rubber and metals.

HOW MANY BRANDS ARE NOW PUBLISHING SUPPLIER LISTS?

We have looked at large brands (over £36 million annual turnover) beyond the Fashion Transparency Index to count the number that are publishing lists of their suppliers. Below, you will find a list of over 200 brands that are publishing their first-tier manufacturers, 60 brands that are publishing their processing facilities and 21 brands that are publishing their raw material suppliers.

We are always pushing brands to provide more information about the people who make their clothes, and you can encourage them to do so too. Always ask the brands you buy #WhoMadeMyClothes. You can do this by tagging your favourite brands on social media and using this hashtag, or you can use our automated email tool to get in touch with them directly.

Brands who publish first-tier supplier lists

First-tier/ Tier One/ manufacturing suppliers are those which have a direct relationship with buyer e.g. production units, Cut Make Trim (CMT) facilities, garment sewing, garment finishing, full package production and packaging and storage.

& Other Stories (H&M group)

Abercrombie & Fitch

Adidas

ALDI-Nord

ALDI SOUTH

Amazon

Ann Taylor

Anthropologie (URBN)

ARROW (PVH)

ASICS

Aldi North

ASOS

Athleta (GAP Inc.)

Autograph (Speciality Fashion Group)

Banana Republic (GAP Inc.)

Berghaus (Pentland Brands)

Berlei (Hanes)

BESTSELLER

BigW (Woolsworth Group)

Black Pepper (PAS Group)

Boden

Bon Prix

Bonds (Hanes)

Boxfresh (Pentland Brands)

Brand Collective

Brooks Sports

Burton (Arcadia)

C&A

Calvin Klein (PVH)

Champion (Hanes)

Cheap Monday (H&M group)

City Chic (Speciality Fashion Group)

Clarks

Cole’s (Wesfarmers Group)

Columbia Sportswear Co.

Converse (NIKE, Inc)

Cos (H&M group)

Cotton:On

Crossroads (Speciality Fashion Group)

Curvation (Fruit of the Loom, Inc.)

David Jones

Debenhams

Designworks (PAS Group)

Disney

Dorothy Perkins (Arcadia)

Dressmann (Varner)

Eagle Creek (VF Corporation)

Eastpak (VF Corporation)

Eileen Fisher

El Corte Inglés

Ellesse (Pentland Brands)

Esprit

Evans (Arcadia)

Factorie (Cotton On Group)

Fanatics

Fjällräven

Forever New

Free People (URBN)

Fruit of the Loom

G-Star

Galeria Inno (HBC)

Galeria Kaufhof (HBC)

Gap

George at Asda (Walmart)

Gildan

H&M

Hanes

Helly Hansen

HEMA

Hermès

Holeproof Explorer (Hanes)

Hollister Co. (Abercrombie and Fitch Co.)

Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC)

HUGO BOSS

Hurley (NIKE, Inc)

Intermix (GAP Inc.)

IZOD (PVH)

JACK&JONES (BESTSELLER)

Jack Wolfskin

Jacqueline de Yong (BESTSELLER)

JAG (APG & Co)

Jansport (VF Corporation)

Jeanswest

JETS Swimwear (PAS Group)

Jockey (Hanes)

John Lewis

Joe Fresh (Loblaw Companies Limited)

Jordan (NIKE, Inc)

Junarose (BESTSELLER)

KangaROOS (Pentland Brands)

Kathmandu

Katies (Speciality Fashion Group)

Kaufland

Kayser (Hanes)

Kipling (VF Corporation)

Kmart Australia (Wesfarmers Group)

Lacoste

Lee (VF Corporation)

Levi Strauss & Co.

Lidl

Lindex

Littlewoods (Shop Direct)

Loblaw

Loft (Ascena)

Lord & Taylor (HBC)

lucy (VF Corporation)

Lululemon

Majestic (VF Corporation)

Mamalicious (BESTSELLER)

Mammut

Marco Polo (PAS Group)

Marimekko

Marks & Spencer

Matalan

MEC

Millers (Speciality Fashion Group)

Missguided

Miss Selfridge (Arcadia)

Mizuno

Monki (H&M group)

Monsoon

Morrisons (Nutmeg)

Name It (BESTSELLER)

Napapijiri (VF Corporation)

Nautica (VF Corporation)

New Balance

New Look

Next

Nike

Noisy May (BESTSELLER)

Nudie Jeans

Old Navy (GAP Inc.)

Only (BESTSELLER)

Only & Sons (BESTSELLER)

Outerknown (Kering Group)

Outfit (Arcadia)

OVS

Patagonia

Pieces (BESTSELLER)

Pimkie

Playtex (Hanes)

Primark

Prisma (S Group)

Puma

R.M Williams

Razzamatazz (Hanes)

Red or Dead (Pentland Brands)

Reebok (Adidas Group)

Reef (VF Corporation)

REI Co-op

Review (PAS Group)

Rider’s by Lee (VF Corporation)

Rio (Hanes)

River Island

Rivers (Speciality Fashion Group)

Rock & Republic (VF Corporation)

rubi (Cotton On Group)

Russell Athletic (Fruit of the Loom, Inc.)

Sainsbury’s – Tu Clothing

Saba (APG & Co.)

Sak’s Fifth Avenue (HBC)

Selected (BESTSELLER)

Sheer Relief (Hanes)

Sisley (Benetton Group)

Smartwool (VF Corporation)

SPALDING (Fruit of the Loom, Inc.)

Speedo (Pentland Brands)

Sportscraft (APG & Co.)

Supré (Cotton On Group)

Target

Target Australia (Wesfarmers Group)

Tchibo

Ted Baker

Tesco

The North Face (VF Corporation)

The Warehouse

Timberland (VF Corporation)

Tod’s

Tommy Hilfiger (PVH)

Tom Tailor

Topman (Arcadia)

Topshop (Arcadia)

Under Armour

Uniqlo (Fast Retailing)

United Colours of Benetton (Benetton Group)

Urban Outfitters (URBN)

Van Heusen (PVH)

Vanity Fair Lingerie (Fruit of the Loom, Inc.)

Vans (VF Corporation)

Vassarette (Hanes)

Vero Moda (BESTSELLER)

Very (Shop Direct)

Victoria’s Secret (L Brands)

Vila Clothes (BESTSELLER)

Voodoo (Hanes)

Wallis (Arcadia)

Warner’s (PVH)

Weekday (H&M group)

White Runway (PAS Group)

Wrangler (VF Corporation)

Yarra Trail (PAS Group)

Y.A.S. (BESTSELLER)

Zalando

Zeeman

Total: 204

Brands who publish processing facilities list

Processing facilities (often referred to as facilities beyond tier 1) are involved in the production of clothing whose activities could involve ginning and spinning, knitting, weaving, dyeing and wet processing, tanneries, embroidering, printing, fabric finishing, dye-houses and laundries.

Adidas

Anthropologie (URBN)

ASICS

ASOS

Banana Republic (GAP Inc.)

Bon Prix

Burton (Arcadia)

C&A

Calvin Klein (PVH)

Champion (Hanes)

Clarks

Converse (NIKE, Inc)

Debenhams

Disney

Dressmann (Varner)

Eileen Fisher

Ermenegildo Zegna

Esprit

Free People (URBN)

Gap

Gildan

G-Star RAW

H&M

Hanes

Helly Hansen

HEMA

Hermès

Jack Wolfskin

Jordan (NIKE, Inc)

Kaufland

Levi Strauss & Co.

Lindex

Lululemon

Monsoon

New Balance

New Look

Nike (Nike, Inc.)

Nudie Jeans

Old Navy (GAP Inc.)

Patagonia

Puma

Reebok (Adidas Group)

Russell Athletic (Fruit of the Loom, Inc.)

Sainsbury’s – Tu Clothing

Target

Tchibo

Tesco

The North Face (VF Corporation)

The Warehouse

Timberland (VF Corporation)

Tommy Hilfiger (PVH)

Topman (Arcadia)

Topshop (Arcadia)

Uniqlo (Fast Retailing)

United Colours of Benetton (Benetton Group)

Urban Outfitters (URBN)

Van Heusen (PVH)

Vans (VF Corporation)

Warner’s (PVH)

Wrangler (VF Corporation)

Total: 60

Brands who publish raw materials supplier list

Raw material suppliers are those which provide the commodity for the production of clothing e.g. cotton, wool, viscose or polyester.

ASOS

Balenciaga (Kering)

Bottega Veneta (Kering)

C&A

Eileen Fisher

Ermenegildo Zegna

Esprit

Gucci (Kering)

H&M Group

Lululemon

Marks & Spencer

Morrisons (Nutmeg)

Nudie Jeans

Patagonia

SAINT LAURENT (Kering)

Tesco

The North Face (VF Corporation)

Timberland (VF Corporation)

United Colours of Benetton (Benetton Group)

Vans (VF Corporation)

Wrangler (VF Corporation)

Total: 21

Please note: We are not endorsing the brands included in this list; this is not a ‘seal of approval.’ While publishing supplier lists is a necessary step towards greater transparency and improved conditions in fashion supply chains, it does not guarantee ethical business practices. However, we hope you find this list informative and continue to ask brands #whomademyclothes.

This list is not exhaustive and only accurate as of April 2020; if you are aware of other large brands (over £36 million annual turnover) that are publishing their suppliers, please let our Policy and Research team know at transparency@

In Autumn 2018 the Environmental Audit Committee wrote to sixteen leading UK fashion retailers, among them M&S, ASOS and Boohoo, asking what they are doing to reduce the environmental and social impact of the clothes and shoes they sell. Today they released their Interim Report on the Sustainability of the Fashion Industry.

Fashion Revolution welcomes the UK Environmental Audit Committee’s findings of their inquiry into the sustainability of the fashion industry. We too want to see a thriving fashion industry in the UK that employs people, inspires creativity and contributes to sustainable livelihoods in the UK and around the world. We agree with the Environmental Audit Committee’s conclusion that the global fashion industry is exploitative and environmentally damaging and that brands and retailers have an obligation to address the fundamental business model.

This report states “We believe that there is scope for retailers to do much more to tackle labour market and environmental sustainability issues. We are disappointed that so few retailers are showing leadership through engagement with industry initiatives.”