Manila, Philippines – The Fashion Revolution Philippines commemorates the victims of the Rana Plaza factory collapse in Bangladesh, in alignment with the Fashion Revolution week held globally. The Rana Plaza factory collapse killed 1,138 textile workers and injured more people became an eye-opener to the world on 24 April 2013. The incident drove the Fashion Revolution movement to push for labor rights transparency and sustainability in the fashion world.

The Fashion Revolution Philippines’ first in-person event held for two days since the pandemic started. The two-day event happened in Moda Laya in commemoration of the 10 anniversary after Rana Plaza disaster. Attendees participated in activities such as clothes swapping, panel discussion with the experts and the screen showing of two documentary films.

The “Se Abrió Paca,” a film made by the Fashion Revolution Guatemala, gave a heartfelt discussion among its viewers just after it was shown with the “True Costs” documentary and the power outage on the first day. Activities on the next day went well with the clothes swapping and panel discussion. Prince Ventura leads the panel discussion with Bianca Gregorio, owner of Moda Laya and founder of Re-clothing, Irene Subang, sustainable fashion designer and educator, and Jamie Naval, founder and CEO of Twenty Kids and Barrio Studios. Our guest experts discussed that the society today needs to focus on the importance of sustainable practices and a circular wardrobe.

Intro by William Persson

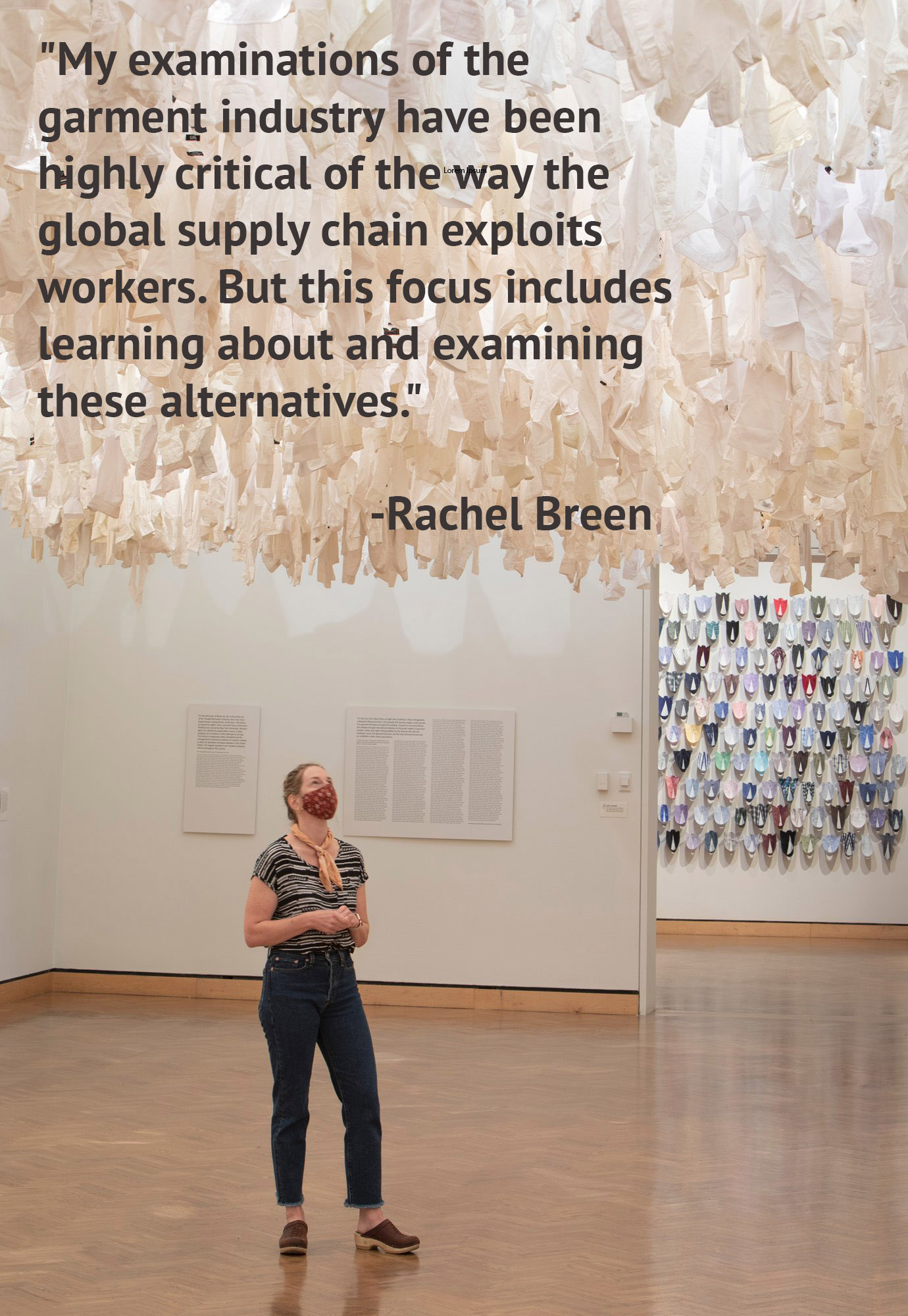

Our Fashion Revolution USA Director of Operations and Community Ashleyn Przedwiecki interviewed Rachel Breen about her work “The Labor We Wear,” which highlights the relationships between the garment industry, workers in the supply chain, and fashion consumers. They address what inspired the pieces and how incidents like the Rana Plaza Factory Collapse have influenced her drive to tell the stories of garment workers. This Q&A has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

ASHLEYN P.: I watched your talk with the Minneapolis Institute of Art and I was so drawn to how you incorporate ethics and social justice into your artistic approach. Can you talk more about your background and what led you to create your current show, The Labor We Wear?

RACHEL B: For years, long before I thought much about garment workers and before the Rana Plaza Factory Collapse, I used my sewing machine as a drawing tool. I still think of my sewing machine as my third arm. When the Rana Plaza Factory did happen, I remember thinking about what it would feel like to be in my 4th-floor studio in NE Minneapolis, sitting at my sewing machine, and have the floor give way beneath me. My horror over the Rana Plaza Factory Collapse and the lives lost and thousands injured gave rise to a deep desire to respond and speak out.

The idea for this exhibition also came from a recognition that the ways garment workers are exploited are not new -that garment workers have been mistreated since the birth of the industrial revolution. I realized this in part because I connected this disaster to a disaster I grew up knowing about: the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire that took place in 1911 in New York City. One hundred forty-six mostly Jewish and Italian immigrants died in this fire, one of the worst worker disasters in the US at that time. I wanted to make work that showed that Americans are not removed from the exploitation of garment workers -but are linked historically as well as through the clothes that we wear.

A.P.: Can you share more about your experience in Bangladesh after the Rana Plaza factory collapse?

R.B.: My experience in Bangladesh was very powerful. I’ll share a few things that were especially important lessons for me. One, is that women suffer daily physical and verbal harassment, are frequently not paid what they are owed and daily work in factories that are extremely unsafe -to a degree that I had not realized. Death and injury happen all the time and we just don’t hear about it. The need for and importance of unions in Bangladesh came into clear focus for me. The labor union movement in Bangladesh is quite nascent but is more important than ever because it is the only collective voice for these women and the only clear way to empower them to address unfair wages and working conditions.

I traveled to Bangladesh with my friend and writer Alison Morse. Both of us are Jewish and were making this connection between the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire and the Rana Plaza Factories collapse. We shared this story with many of the women we met when we would explain why we were there. Many of them told us we should meet with the Tazreen Factory fire survivors because that tragedy was even more familiar to the Triangle Shirtwaist fire so we did. Learning about this other tragedy it dawned on me that there were probably so many disasters that I did not know about. We did interview many survivors of the Tazreen Factory fire and it was just as heartbreaking as speaking to the survivors of the Rana Plaza Factory Collapse. I was constantly surprised by the willingness of women to share their stories. Women want to be heard.

A.P.: This exhibition is one of many you’ve worked on that focuses on the untold stories of garment workers and spotlighting the people behind our clothing. What was the inspiration behind this? And how do you turn an idea into an art piece or a full exhibition?

R.B.: The more I have learned about the global garment industry the more I have felt outraged and deeply concerned about the treatment of workers, and the ramifications of overproduction on the part of corporate brands, overconsumption by the American public, the waste all this causes, and how it impacts our planet. It is absolutely horrifying, and I hope that my work can contribute to behavior changes, but more importantly, lead to policy changes that address this industry.

As an artist, I am very curious and interested in how materials convey meaning. Once I began to work on this issue I thought a lot about the materials that would help tell the many aspects of the story of Rana Plaza, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, the daily labor of garment workers, and our connection, as consumers to these stories. I spend a lot of time in my studio playing with materials: taking things apart, arranging them, rearranging them until they start to speak the way I want them to. This focus on exploring materials in my work and the public response to it has inspired my continued journey of making work on this subject.

A.P.:What are you hoping people will come away with after exploring one of your exhibitions?

R.B.: I hope that people feel moved in some way. I hope the work encourages people to reflect on the themes in my work and that it provides them with a larger lens through which to look at the world and their (our) things.

A.P.: Did you imagine your installation to become as popular and moving as it has been to so many people?

R.B.: That is a great question! No, I imagined and hoped but I did not know what an impact the work would have. With a project this large, you don’t really know what it will look like until it’s finished and installed. I was so nervous! I spent months working on it and finally when it was up I couldn’t believe how powerful it was — I was so happy and also sorrowful — you can’t look at the work and not feel both emotions.

A.P.: How does the sewing machine play a role in your work as an artist?

R.B.: I am interested in the creative possibilities of the sewing machine. I use it to draw, create installations and initiate socially engaged public projects. I am a maker, yet much of my work involves the opposite: I “unmake” things and “dismantle” ways of seeing and believing. I am interested in the sewing machine as a deeply symbolic and also (im)practical object.

A.P.: You use art as a tool for social change, can you talk more about how you see the relationship between art and social justice movements?

R.B.: I think that art can help the public look at a problem or a situation with new perspectives and in a way that is empowering. Successful community organizing requires building power, and I believe building power begins with having new insights and believing that change is possible.

A.P.: Do you have any advice for young designers, artists, or leaders as they challenge/confront the deeply ingrained issues within our current fashion industry?

R.B.: Work from a place of community. That means building community so that you can collectively challenge, confront, advocate and build towards your vision. Have a vision of the change you want to see, otherwise, you won’t have a sense of direction. Engage, be open to being wrong and be brave!

A.P.: What is next for you as you pursue a continuation of this body of work? How do you hope it might unfold and drive change?

R.B.: My examinations of the garment industry have been highly critical of the way the global supply chain exploits workers. But this focus includes learning about and examining these alternatives. I’m currently envisioning the development of visual language that explores alternative economic models to capitalism.

Rachel Breen received her MFA from the University of Minnesota and is involved in creating her pieces using non-traditional materials and exhibition spaces that aim to inspire community engagement in social justice initiatives. In “The Labor We Wear,” she utilizes clothing to hold consumers accountable for the life cycle of garments, from unsafe working conditions to textile waste. The work makes these relationships visible in order to break the cycle.

Fashion Revolution’s theme for 2017 is Money Fashion Power which will be exploring the flows of money and structures of power across the fashion supply chain.

“There is nothing more important than performance, and fashion brands have to perform because of this greed – not a percent or two per year, but at least 10 percent quarterly, even when we’re talking about billion-dollar businesses. There is no end to the greed, so the brands are spreading themselves thin”

said trend forecaster Li Edelkoort in an interview with Deutsche Welle published this week.

Tomorrow is the fourth anniversary of the Tazreen Fashions fire in Dhaka Bangladesh. All of the garment workers were on an overtime shift to complete an urgent order when the fire alarm sounded, but managers ordered them to carry on working. As the smoke and fire spread through the building and workers eventually tried to escape, they found that iron grilles barred the windows and the collapsible gate was locked. None of the fire extinguishers appeared to have been used which suggests workers had not received fire safety training. 112 workers died and more than 200 were injured. The official who led the inquiry into the fire said

“Unpardonable negligence of the owner is responsible for the death of workers.”

After the Tazreen fire, factories were told to replace collapsible gates and lockable doors with fire-proof doors so there was always a safe exit point in the event of a fire. In the Bangladesh Accord’s initial inspection of 1600 garment factories, it was found that over 90% had lockable, collapsible gates. According to industry insiders, around 40% of all operational garment factories still have these gates, four years later.

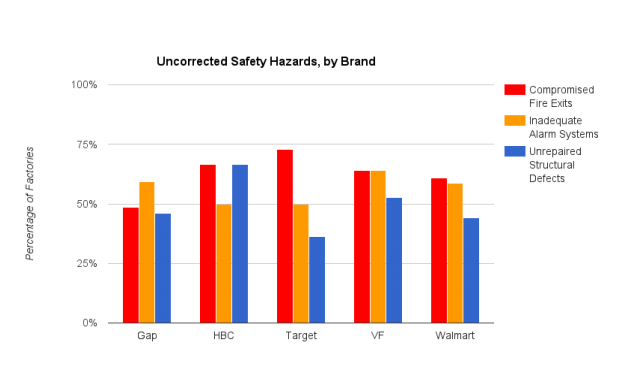

A new report published this week Dangerous Delays on Worker Safety found that of the 107 factories labelled “on track” by The Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, 99 were still falling behind in one or more safety categories. In light of Li Edelkoort’s observation that brands are spreading themselves thin, it comes as little surprise to find that brands in the Alliance, which includes brands such as Walmart, Target, Gap inc, VF Corporation (which owns Lee, Wrangler, The North Face, Vans, Timberland and others and has just published its factory lists) have yet to put in place the life-saving safety changes they pledged following the Rana Plaza disaster, which occurred five months after the Tazreen fire. 62% of factories still lack viable fire exits, 62% do not have a properly functioning fire alarm system and 47% have major, uncorrected structural problems. Deadlines for these safety measures to be implemented were supposed to be 2014/15 but have now been moved to 2018, the end of the 5 year period over which the Alliance extends.

Are brands and factory owners really so concerned with the bottom line that they cannot afford to prioritise the installation of something so basic to worker safety as a fire-proof door and the removal of locks from existing doors?

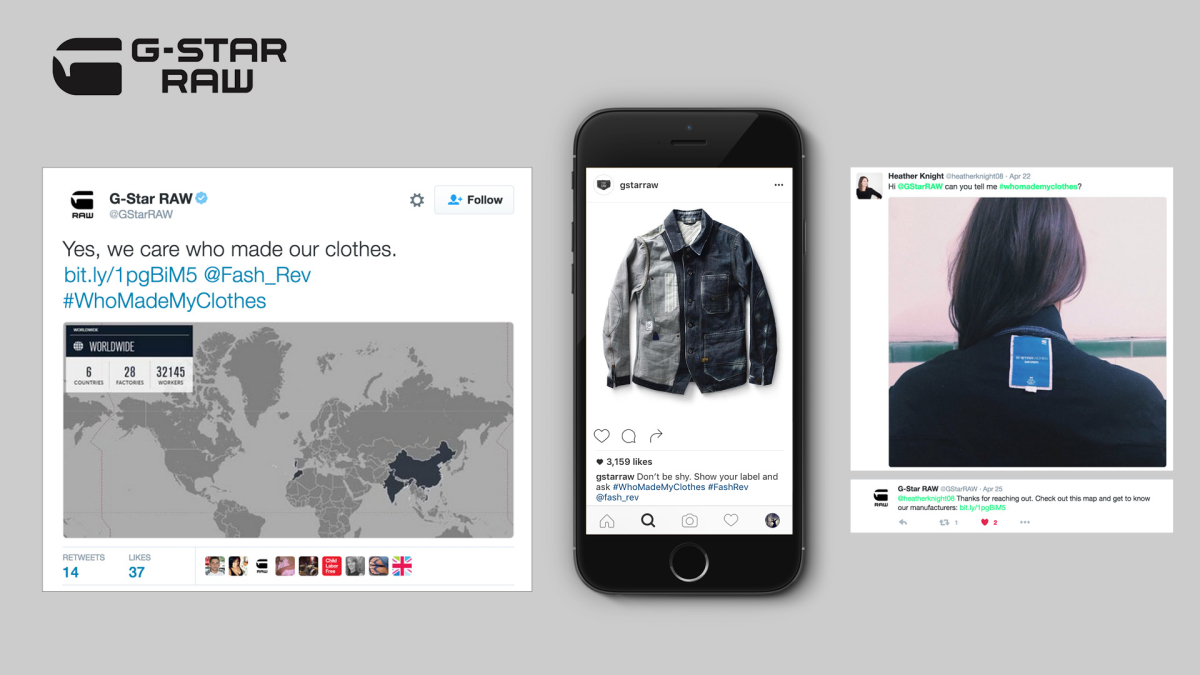

Since the Tazreen fire and Rana Plaza disaster, human rights issues are certainly more visible than ever before and there is ongoing pressure on global fashion brands to become more transparent. Companies are now being held to a higher standard and they are cognisant of this change. During Fashion Revolution Week in April, over 70,000 fashion lovers around the world asked brands #whomademyclothes on social media, with 156 million impressions of the hashtag. G Star Raw, American Apparel, Fat Face, Boden, Massimo Dutti, Zara, Jeanswest and Warehouse were among more than 1250 fashion brands and retailers that responded with photographs of their workers saying #Imadeyourclothes. Read more about our impact here.

However, the harsh reality is that basic healthy and safety measures still do not exist for millions of people who make our clothes and accessories. On 11 November 2016, 13 people died in a factory making leather jackets on the outskirts of Delhi. The front of the building had been shuttered with a metal grill which prevented the workers escaping the blaze. Deadly accidents are still commonplace in fashion supply chains and not enough has been done by brands and retailers to prevent more fashion victims; victims of neglect, oversight and the pursuit of profit.

Scott Nova, executive director of the Worker Rights Consortium says:

“What motivated Walmart and Target to do the right thing is public embarrassment. We are three and a half years on [from Rana Plaza] and they assume memories are fading.”

We have the power and, I believe a duty, to let these brands know that our memories of the Rana Plaza disaster, the Tazreen Fashions fire, and the many other tragedies which have ocurred in the name of fashion, are not fading. By asking the question #whomademyclothes we are applying pressure in the form of a perfectly reasonable question that fashion brands should be able to answer. We are asking them to publicly acknowledge the people who make our clothes; millions of people working in factories, fields, homes and other hidden places around the world. Tragedies like the Tazreen Fashions fire are preventable, but they will continue to happen until every stakeholder in the fashion supply chain is responsible and accountable for their actions and impacts.

As Li Edelkoort said, fashion brands are spreading themselves thin. As their customers, we can help make sure they start to get their priorities right and redress the imbalances of power in the fashion supply chain.

Header photo credit: A young garment worker by Claudio Montesano Casillas

Four million garment workers, mostly women, toil in 5,000 factories across Bangladesh, making the country’s $25 billion garment industry the world’s second largest, after China.

Garment workers generally are paid low wages with few or no benefits and often struggle to support their families. Many risk their lives to make a living.

On November 24, 2012, a massive fire tore through the Tazreen Fashions Ltd. factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh, killing more than 110 garment workers and gravely injuring thousands more.

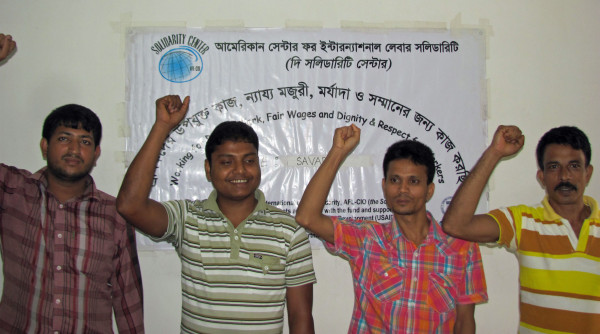

In the wake of this disaster, garment workers throughout Bangladesh are standing up for their rights to safe workplaces and living wages. With the Solidarity Center, which partners with unions and other organizations to educate workers about their rights on the job, garment workers are empowered with the tools they need to improve their workplaces together.

Learn more about the Solidarity Center’s work in the global garment industry

DISASTER STRIKES TAZREEN

On November 24, 2012, women and men working overtime on the Tazreen production lines were trapped when fire broke out in the first-floor warehouse. Workers scrambled toward the roof, jumped from upper floors or were trampled by their panic-stricken co-workers. Some could not run fast enough and were lost to the flames and smoke.

Hundreds of those injured at Tazreen, like Tahera (above), will never be able to work again. Survivors say they endure daily physical and emotional pain, and often are unable to support their families because they cannot work and have received little or no compensation.

Some 80 percent of export-oriented ready made garment (RMG) factories in Bangladesh need improvement in fire and electrical safety standards, despite a government finding most were safe, according to a recent International Labor Organization (ILO) report.

TAZREEN NOT UNIQUE

The Tazreen fire was not an isolated incident.

Months after the Tazreen disaster, more than 1,000 garment workers were killed when the Rana Plaza building collapsed. Workers were forced to return to the building despite the warnings of structural engineers that the building was unsound.

In the four years since Tazreen, fires, building collapses and other tragedies have killed or injured thousands of garment workers in Bangladesh, according to data collected by the Solidarity Center.

FACTORIES CAN BE MADE SAFE

The Tazreen fire and Rana Plaza collapse were preventable. Workers at Tazreen and Rana Plaza did not have a union or other organization to represent them and help them fight for a safe workplace.

Without a union, garment workers often are harassed or fired when they ask their employer to fix workplace safety and health conditions. They are not trained in basic fire safety measures and often their factories, like Tazreen, have locked emergency doors and stairwells packed with flammable material.

Unions have helped to improve these conditions.

They have joined together to form workplace unions and bargain for safe working conditions, better wages and respect on the job.

UNIONS SAVING LIVES

Worker voices have yielded real results.

Over the past few years, the Solidarity Center has held fire safety trainings for hundreds of garment factory workers. Workers learn fire prevention measures, find out about safety equipment their factories should make available and get hands-on experience in extinguishing fires.

When women workers form unions, they improve their working conditions. Through Solidarity Center workshops and leadership training, more women are running for union office. Women now make up more than 61 percent of union leadership in newly formed factory level-unions.

CHANGE IS POSSIBLE

Salma (below), a garment worker, and her co-workers faced stiff employer resistance when they sought to form a union. With assistance from the Solidarity Center and the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation (BGIWF), to which their factory union is affiliated, workers negotiated a wage increase, maternity benefits and safe drinking water. The factory now is clean, has adequate fire extinguishers on every floor, and a fire door has replaced a collapsible gate.

To learn more about garment workers in global supply chains and how the Solidarity Center supports them, visit www.solidaritycenter.org.

24 April is the most important day for fashion. But not because it’s Fashion Revolution Day. It’s because over 1000 men and women, with families, hopes and dreams just like us, lost their lives while making our clothes.

Did you know that 80% of our fashion is made by 18-24 year old young women around the world? Sadly the only time we hear about these millennial makers is when tragedies such as Rana Plaza occur.

When we ask more about them, we can change their lives. Let’s never forget Rana Plaza and keep asking our favourite brands #whomademyclothes?

By Balmi Chisim, Solidarity Center

More than 1,100 garment workers died on 24 April 2013 when the Rana Plaza building collapsed in Bangladesh, a preventable disaster that injured thousands more workers in the world’s worst industrial accident in years.

Yet their lives likely would have been spared ‘if any of the factories (in the building) had a union’ says union leader Salma Akter Meem. Salma made her observation as she took part this month in a 10-week-long Solidarity Center fire safety training program, one of nearly a dozen such programs the Solidarity Center has held in the past two years.

Salma, 26, started working at age 14 in the garment industry. She says the Rana Plaza building collapse made her co-workers aware of safety issues, and they formed a union September 2013 so they could have a collective voice to create positive changes in their workplace, including making their factory safe.

Blocked from Factory for Trying to Form a Union

Forming a union was not easy, she says. The employer refused to recognize their union even after it received official government registration, which is required in Bangladesh. Employers retaliated against union members, especially against workers on the factory union’s executive committee, Salma says.

‘I was harassed and my union members were banned from entering the factory while we raised our voices and brought attention to the Accord that there was excessive machinery load on the floor and safety issues’ says Salma, who now is general secretary of the factory union.

The Bangladesh Fire and Building Safety Accord, a legally binding agreement in which nearly 200 corporate clothing brands paid for garment factory inspections, was set up after international outrage over the Rana Plaza and the Tazreen Fashions Ltd. tragedy five months earlier, in which more than 100 garment workers were killed when the factory burned down. Since the Tazreen fire, 34 garment workers have been killed in fire incidents and 1,023 workers injured, according to data compiled by the Solidarity Center staff in Bangladesh, according to data compiled by the Solidarity Center in Dhaka, the capital.

Following inspections mandated by the Accord, dozens of garment factories were closed for safety violations and pressing safety issues were addressed.

Standing Strong Together and Winning

Even though some workers were not allowed to work after they formed a union, Salma and her co-workers did not give up in the face of such employer resistance. With assistance of the Solidarity Center and the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation (BGIWF), to which their factory union is affiliated, workers got their jobs back with full compensation for the time they were prevented from working.

Negotiations and discussions with management, finalized in February 2015, have resulted in positive changes, Salma says, with workers getting a wage increase, maternity benefits and safe drinking water. The factory now is clean, has adequate fire extinguishers on every floor, and a fire door has replaced a collapsible gate.

“Changes are possible if you have union and you can make it work.”

Back at the Fire and Building Safety class, Salma says she is ‘learning here not only for me, but also for my factory and family’. She says if workers are safe in a factory and not afraid to raise their voices for a safe and healthy work environment and living wages to support themselves, their workplace contributions will increase, benefiting the employer—and the country.

Header photo: Bangladesh garment workers take part in Solidarity Center fire safety training. Credit: Jennifer Kuhlman/Solidarity Center

80% of our fashion is made by women who are only 18 – 24 years old. Sadly we only hear about these women when terrible tragedies occur, be it the Rana Plaza disaster in Bangladesh in 2013, the horrific fire at Ali Enterprises in Pakistan in 2012, or Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York in 1913. The hopes and dreams of the women behind our fashion are eclipsed by heartbreaking headlines that hound the fast fashion industry.

Made in Pakistan is the story of two incredibly resilient women who make our clothes. They don’t want our pity. They want us to know them. We hope this short will move you to care about them and ask #whomademyclothes.

Rubina: I am 22 years old and wanted to be a doctor. Then my father got sick, so here I am, many years later, still at a factory stitching college sweatpants and hoodies that go to America. I don’t want you to feel sorry for me. I used to be shy and scared in the factory environment. But after all the injustices I’ve seen happen here, I’ve become a labor organizer. I go to management to demand that we are not harassed, paid on time, given proper food to eat. You would not believe the things I have seen. Stitching all day long my mind wanders and I think about you often. You having fun, wearing these hoodie on campus. I wonder if you think about me ever? The woman who made that for you. I am taking English classes at night. So that one day I can at least get an office job.

Lubna: After my husband left me and my infant daughter, I had to find ways to care for her and my aging parents. So here I am, many years later working at a garment factory. As I pull threads out of hoodies and do the final inspection, I sneak glances at the clock. My days are long and I miss my daughter so much. The other women on the line help me get through my days. We share secrets and the grief that is buried deep in our hearts. When the sun starts to set, its my favorite part of the day because I get to go home to my daughter. I don’t have very many dreams of my own anymore. I just hope for a better life for my daughter. I often imagine university students hanging out, wearing the hoodies that I helped make. I hope you know that my daughter and my life are woven into the threads of your hoodie.

Making of the film: Made in Pakistan is a part of Remake’s Meet the Maker series. We traveled and visited fabric mills, factories, dormitories and homes throughout the world in search of the women who make up fashion’s supply chain. So far we’ve been to Haiti, India, Pakistan and China, to sit down and eat meals, listen and learn about the triumphs and the heartaches of the women who make our clothes.

This film is personally very meaningful to me. I was born and raised in Karachi, Pakistan. I have for the last decade worked across brands, factory managers, government and unions leaders to invest in the lives of the people who made our clothes. We were fortunate to have partnered with an amazing Pakistani film crew. Our cinematographer Asad Faruqi and producer on the ground Haya Iqbal were thoughtful and persistent in capturing this story (and their recent documentary A Girl in a River has just won an Oscar!).

We hope you enjoy a glimpse into Lubna and Rubina’s life and think about them the next time you put on a hoodie or a pair of sweatpants.

H&M ha declarado la “Semana Mundial del Reciclaje” del 18 al 24 de abril de 2016 con una campaña de marketing de gran envergadura que pretende recoger 1.000 toneladas de ropa usada durante esa semana y reciclarlas para convertirlas en nuevas fibras. Fashion Revolution desafió este objetivo, señalando que sólo una pequeña fracción de las 1.000 toneladas propuestas como objetivo pueden convertirse en nuevas fibras textiles ya que la tegnología para ello aún no existe. La organización también desafió lo desconsiderado del momento para la promoción, que coincide con el 24 de abril, justo cuando hace tres años 1.134 personas murieron en Rana Plaza, en Bangladesh, haciendo ropa para cadenas minoristas, y H&M es el mayor productor de prendas en Bangladesh.

Orsola de Castro, co-fundadora de Fashion Revolution ha dicho: “Esta semana, de todas las semanas, H&M debería trabajar en solidaridad con el resto de nosotros para marcar el aniversario de la tragedia de Rana Plaza. Debería ser un momento para todos nosotros para honrar a los trabajadores textiles, aquellos que han muerto en tragedias industriales de la industria textil y aquellos que todavía hoy sufren en la cadena de suministro textil. ”

Fashion Revolution también señalaba el lenguaje confuso usado para describir el impacto de la iniciativa de reciclaje de H&M. Estábamos emocionados de que tanta gente mostrara su apoyo por una mayor transparencia y ayudara a comenzar una conversación sobre temas controvertidos relacionados con la exportación de ropa de segunda mano a países en desarrollo.

“Estamos contentos de que H&M haya admitido las verdaderas cifras de lo que se revende, lo que se reusa y lo que se convierte en nuevas fibras y de que cambiara el objetivo en su web en consecuencia. Esto ha sido algo muy influyente de hecho – usamos nuestra voz colectiva de manera moderada y hicimos que una de las mayores corporaciones del mundo diera un paso hacia una mayor transparencia.

Esperamos que H&M elimine su cupón de descuento en el futuro para no alentar un mayor consumismo entre sus jóvenes consumidores – eso sería el próximo paso lógico al abordar correctamente el tema de los residuos textiles. ”

H&M respondió con el siguiente comunicado: “Tan pronto como Fashion Revolution nos hizo conscientes de sus preocupaciones, comunicamos claramente qe no tenemos la intención de convertir en esta semana en particular como una Semana Mundial del Reciclaje de manera recurrente en el futuro, y hemos ofrecido inmediatamente elegir otra semana si hiciéramos otra Semana Mundial del Reciclaje en el próximo año o siguientes. ”

Fashion Revolution Week tiene lugar del 18 al 24 de abril en 89 países en todo el mundo. Por favor únete y ayuda a aclamar a los verdaderos héroes. Visita www.fashionrevolution.org para encontrar un evento cerca de ti. Juntos podemos hacer que el cambio ocurra.

Por favor ¡apoya a Fashion Revolution para ayudarnos a hacer nuestro mensaje más fuerte! Cada donación nos ayudará a dar voz a todos los implicados en la cadena de producción. Gracias por ser parte de este movimiento y por ayudarnos a seguir siendo fuertes.

Nota para prensa

- Millones de personas saldrán a la calle durante la Fashion Revolution Week para despertar conciencias y hacer preguntas sobre las condiciones a las que se enfrentan los trabajadores textiles y la persistente falta de derechos humanos en la industria de la moda, y para homenajear a la gente que está detrás de lo que llevamos – desde el granjero a la hilandera, la tintorera, sastres y más.

- Durante la semana del 18 al 24 de abril de 2016, te animamos a que pienses lo que hay en tu armario. Si tienes prendas sin estrenar, ¿podrías hacer algo con ellas en vez de deshacerte de ellas (en H&M o en cualquier otro lugar)? Lo podrías intercambiar con un amigo que lo aprecie más, o tal vez lo podrías modificar para que lo puedas seguir amando más tiempo. O por qué no probar nuestra Haulternative, y descubrir 8 maneras de renovar tu armario sin comprar nuevas prendas.

- Fashion Revolution Week se celebra del 18 al 24 de abril de 2016, no te olvides de preguntarle a tu marca favoria #quienhizomiropa o #whomademyclothes.

The three-year anniversary of the November 24, 2012, fire that killed 112 Bangladesh garment workers at the Tazreen Fashions Ltd., factory offers a time to reflect on garment workers’ ongoing struggle for workplaces where they will not be killed or injured and for jobs that will support their families.

The Tazreen fire was preventable, as was the collapse of the multistory Rana Plaza factory five months later in which more than 1,130 garments workers died and thousands more were severely injured.

Workers at Tazreen and Rana Plaza did not have a union or other organization to represent them and help them fight for a safe workplace. Without a union, garment workers say they are harassed and even fired when they raise safety issues with their employer. They are not trained in basic fire safety measures and often their factories, like Tazreen, have locked emergency doors and stairwells packed with flammable material.

Despite the many obstacles to forming organizations and achieving a voice at work, garment workers are at the forefront of pushing for change at their factories. With our strong and long-term grassroots connections in Bangladesh, the Solidarity Center allies with garment workers to provide ongoing training for factory-level union leaders on topics such as gender equality, workers’ legal rights and fire safety.

This photo essay gives voice to the sorrow, but also the hope, of the 4 million workers who toil in Bangladesh garment factories.

1. Bangladesh’s 4 million garment workers, mostly women, toil in 5,000 factories across the country, making the $25 billion garment industry the world’s second largest, after China. Yet many risk their lives to make a living. In the three years since the fatal Tazreen Fashions Ltd. factory fire, some 31 workers have died and at least 935 people have been injured in garment factory fire incidents in Bangladesh. Credit: Law at the Margins

2. Some 112 garment workers were killed in a blaze that swept through the Tazreen factory on November 24, 2012. Hundreds more were injured and like Tahera (above), will never be able to work again. Survivors say they endure daily physical and emotional pain, and often cannot support their families because they cannot work and have received little or no compensation. Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

3. Tens of thousands of Bangladesh garment workers held rallies on May Day this year to highlight the need for the freedom to form worker organizations to ensure safe and healthy workplaces. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

4. With few jobs available that pay a living wage, more than 600,000 Bangladeshi workers migrate each year. Yet, “after two years, after three years, they are not getting their salary,” says Sumaiya Islam, director of the Bangladesh Migrant Women’s Organization (BOMSA). “After spending $1,000 (to labor recruiters), they are not getting paid.” Credit: Shahjadi Zaman

5. Migrants from Bangladesh also risk their lives when going overseas for jobs. In June, Bangladesh families rallied to demand the government punish traffickers after many Bangladesh workers were among migrants stranded on abandoned boats by unscrupulous labor traffickers. “I did not get anything to eat for 22 days and just survived by eating tree leaves,” Abdur said, describing his journey to Malaysia. Credit: Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

6. On April 24, 2013, the multistory Rana Plaza factory collapsed, a preventable tragedy that killed more than 1,100 garment workers and injured thousands more. On the two year anniversary in April, family members and friends gathered at the site of the building to commemorate their loss. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

7. Thousands of garment workers, like Mosammat Mukti Khatun (above, looking at the Rana Plaza rubble) who survived the Rana Plaza disaster, remain too injured or ill to work and support their families. Survivors and the families of those who lost loved ones in the collapse say they are struggling to make ends meet, unable to pay rent, send their children to school or provide for other basic needs. Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

8. Days before tens of thousands of Bangladesh garment workers rallied on the two-year anniversary of the Rana Plaza collapse, the ITUC released a report that found “a severe climate of anti-union violence and impunity prevails in Bangladesh’s garment industry. The violence is frequently directed by factory management. The government of Bangladesh has made no serious effort to bring anyone involved to account for these crimes.” Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

9. The Solidarity Center launched the Bangladesh Worker Rights Defense Fund in April 2014, following an increase in violence and harassment against workers who were seeking to form unions to protect their health and rights on the job. Donations of more than $15,500 helped to provide costly medical treatment for organizers beaten or attacked while speaking to workers about their rights, and temporary food and shelter for workers fired for trying to improve their workplace. Credit: Solidarity Center/Shawna Bader-Blau

10. Despite employer and government resistance to workers’ efforts to form organizations to improve job safety, in the Dhaka export processing zone alone, 40 of the 103 factories include workers’ welfare associations, which are similar to unions. Credit: Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

11. Women garment workers primarily fuel Bangladesh’s $25 billion a year garment industry, yet women are “still viewed as basically cheap labor,” says Lily Gomes, Solidarity Center senior program officer for Bangladesh. “There is a strong need for functioning factory-level unions led by women,” says Gomes, who is leading efforts to help empower women workers to take on leadership roles at factories and in unions throughout Bangladesh. Credit: Solidarity Center/Kate Conradt

12. With strong and long-term grassroots connections in Bangladesh, the Solidarity Center provides ongoing training for garment worker union leaders on topics such as gender equality, workers’ legal rights and job safety. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

13. Garment worker union leaders sharpen their skills through regular Solidarity Center workshops, such as this one on financial management. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

14. Hundreds of garment worker union leaders have participated in this year in the Solidarity Center’s 10-week fire safety certification course. “People who worked at Tazreen and Rana Plaza had no training and had no union,” says Saiful, who took part in a recent fire training. “This training is about making sure those things never happen again.” Credit: Solidarity Center/Rakibul Hasan

On 2nd December 2015, Fashion Revolution launched its first white paper, It’s Time for a Fashion Revolution, for the European Year for Development. The paper sets out the need for more transparency across the fashion industry, from seed to waste. The paper contextualises Fashion Revolution’s efforts, the organisation’s philosophy and how the public, the industry, policymakers and others around the world can work towards a safer, cleaner, more fair and beautiful future for fashion.

“Whether you are someone who buys and wears fashion (that’s pretty much everyone) or you work in the industry along the supply chain somewhere or if you’re a policymaker who can have an impact on legal requirements, you are accountable for the impact fashion has on people’s lives. Our vision is is a fashion industry that values people, the environment, creativity and profit in equal measure”

explained Sarah Ditty on behalf of Fashion Revolution.

Carry Somers, co-founder of Fashion Revolution, said

“Most of the public is still not aware that human and environmental abuses are endemic across the fashion and textiles industry and that what they’re wearing could have been made in an exploitative way. We don’t want to wear that story anymore. We want to see fashion become a force for good.”

The paper was launched at a joint event with the Fair Trade Advocacy Office in Brussels and hosted by Arne Leitz, Member of the European Parliament to mark the European Year for Development.

The event included contributions by Dr Roberto Ridolfi, Director at the European Commission Directorate-General for Development and Cooperation, Jean Lambert MEP, and Sergi Corbalán, on behalf of the Fair Trade movement.

“We need an integrated approach, from cotton farmer to consumer, and we need EU support,”

explained Sergi Corbalán.

Fashion Revolution lays out its five year agenda in the paper. By 2020, Fashion Revolution hopes that:

- The public starts getting some real answers to the question #whomademyclothes

- Thousands of brands and retailers are willing and able to tell the public about the people who make their products

- Makers, producers and workers become more visible

- The stories of thousands of actors across the supply chain are told

- More consumer demand for fashion made in a sustainable and ethical way

- Real transformative positive change begins to take root.

With many congratulations on the launch of the white paper, Dr Roberto Ridolfi proclaimed:

“My ambition, as of tomorrow, is to become a Fashion Revolutionary!”

Although our resources are free to download, we kindly ask for a £3 donation towards booklet downloads. Please donate via our donations page

[download image=”https://www.fashionrevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/FRD_resources_thumbnail_whitepaper.jpg”]Download our White Paper ‘It’s time for a Fashion Revolution‘, published December 2015.

Download[/download]

Fashion Revolution also launched a new video for the European Year for Development at the event: Why We Need a Fashion Revolution.

I am sure that you have a closet overflowing with clothing. Chances are you might even have items that still have the swing tickets attached. Have you ever looked at the care label to see where your clothing was manufactured? Fast fashion isn’t going anywhere anytime soon. In fact fast fashion was created for this simple reason: to get us buying more and more and without much thought into where these garments are made.

I am hoping that by the time you finish reading this piece, something would have shifted. For one you will take a look at the care labels of your clothing and find out who is responsible for it and that you will hopefully reevaluate your shopping habits. Fast fashion companies cut corners, they use cheaper fabrics and cheap labor. It is simply exploitation. There is the argument that fast fashion creates jobs but when people are exploited it simply isn’t right.

Cape Town was aflutter recently when H&M (Hennes & Mauritz) opened its first store in South Africa. More stores are planned including Johannesburg’s Sandton City as well as others in Southern, East and West Africa.

It is always great to have brands open stores in our country, least of all when you know that jobs will be created. It is reported that about 600 jobs were created leading up to the opening of the V&A Waterfront and Sandton City stores. Staffers, around 60, were sent to Sweden for training. H&M plans to have as many as 1 500 people employed within the next 12 months.

The buzz continues but there is one fundamental problem with brands like these and it seems very few people know what really happens behind closed doors. In this case, behind the doors of the factories that produce these garments. This lack of knowledge was evident from the social media images from fashion bloggers to local personalities applauding H&M on their opening.

It was not long ago, in fact only two years prior, in April 2013 when the deadliest industrial disaster in the history of clothing manufacturing took place. The collapse of the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh, claiming the lives of 1 138 of its workers.

Two years after this tragedy, H&M is still behind on correcting the fire and safety hazards in its factories in Bangladesh according to the joint report released by the International Labor Rights Forum, Clean Clothes Campaign, Maquila Solidarity Network, and Workers Rights Consortium. These fire and safety hazards are the working conditions their workers are forced to work under making sure that fast fashion reaches our stores timeously. Repairs, which include installation of fireproof doors and the removal of locking or sliding doors from fire exits are some of the issues that have not been addressed.

These are repairs that affect the staff working in these factories. If not dealt with, it could have disastrous outcomes, like that of April 2013. It appears that more attention is placed on pushing out the orders as opposed to the people who make these garments. Will these factories get away with these hazardous conditions if they were in developed countries? No! Cheap labor is simply that; cheap. Bangladeshi workers who sew for H&M toil in extremely dangerous conditions. So can you really say that their fashion is cheap? Cheap in price definitely but costly on the scale of human lives. Par Darj, the country manager for H&M South Africa described H&M’s merchandise as “democratic fashion” high quality, easy and affordable for people who ordinarily might not be able to buy fashion. How democratic is this model if H&M chose to open their first store at the V&A Waterfront? The only people who benefit from the fast fashion system are the executives who are some of the richest people in the world.

The H&M store in Cape Town is 4700 square meters and is said to be one of their biggest stores in the world. Rumor has it that there might be a section carrying local designers in the near future. Could this be why they are exploring the feasibility of opening a local manufacturing facility? Par Darj said H&M already has a production factory in Ethiopia, opened in 2014. “We will see what is possible in South Africa”. One would hope that the working conditions in this factory are safer than the one in Bangladesh or the potential of a factory opening in South Africa will not cost anyone their life.

Are South African malls in the future only going to comprise of top international brands? The likes of Burberry, Forever 21, Top Shop, Zara etc. It could be, unless you reevaluate your shopping habits.

The True Cost film will make you rethink your fast fashion addiction. I can’t help but think of the interview with Shima Akter, a 23-year-old Bangladeshi garment worker who was beaten by her factory supervisors for organizing and leading a workers’ union in the hopes to get better working conditions ‘I don’t want anyone wearing anything which is produced by our blood.’

I encourage you to watch The True Cost to understand just where your clothing comes from and the price others are paying for it.

Who Makes Our Clothing? | Livia Firth | The True Cost

Tesco may not be the first brand that comes to mind when you consider ethical trading. However their F&F clothing range aims to deliver “great products at great prices from factories that (they) are proud of”, and they claim that they ‘want to be a force for change in both reducing our social and environmental impact’. But when a your child’s school polo shirt costs just £2.50 for 2, you do wonder what corners are cut to achieve the incredibly low price.

Since the tragedy of the Rana Plaza, working conditions in Bangladesh’s clothing factories have been put under scrutiny. We, the consumers, have been forced to consider #whomademyclothes? Tesco’s shiny corporate website naturally says all the things that we want to hear. So, in an attempt to dig deeper and find out what Tesco is actually doing, I spoke to Dani Baker, Corporate Responsibility Manager of F&F here in the UK, and Mashuda Begum, Senior Manager of Responsible Sourcing, working on the ground in Bangladesh.

Q: What practical steps is Tesco taking to improve working conditions in Bangladesh? Dani: We are committed to ensure that anyone who supplies any products to F&F has the best possible condition for their workers. We understand that this cannot be done from afar, but by working in direct partnership with all our suppliers, which is why we have people around the world working on the ground. In Bangladesh we have a team of about 60 people who not only check things like the fire and safety standards of factories, but also make sure that corners are not cut. So that the factories are a good place to be with staff being paid a decent wage, on time and wider social economic issues are being addressed – like ensuring that their children can go to school.

We have also been proud to support a number of initiatives, including programmes like the Benefits for Business and Working (BBW) training, run by Impactt, since 2010. Through this scheme, we have seen real improvements in factories as they have looked at ways to not only to improve the efficiency of the production line and the quality of the work, but also at human resources, communication and worker welfare. The results have been amazing in providing workers with reduced hours, better pay and benefits. Another project, Phulki, is a women’s empowerment scheme which provides crèches for female workers so they have somewhere safe to leave their children whilst they work- helping to protect them from the possible dangers of drowning, sexual abuse or even trafficking.

All of the factories we use have regular independent audits. We don’t just take the audit results at face value, our team on the ground ensure a more long-term collaborative approach; this includes a number of interventions such as running interactive workshops with our factories, so we can work with them on problems that arise, and support them running their factory safely and legally.

Q: That’s great that Tesco is regularly in the factories. But, how do you know that what they show you truly reflects everyday practice? Dani: This is why it is important to us that we build up long-term collaborative partnerships with our suppliers, so we can have a real insight into their everyday practices. The majority of the factories we use, we have worked with for over five years. However, the product is also a good indicator as to whether everything is OK in the factories. We regularly check the quality and if there are any persistent issues, this tends to flag up that there may be a problem.

Q: Your website states that your team in Bangladesh are there to ‘build relationships and to ensure decent working standards.’ But what does that mean in practice? Mashuda: It means providing a safe and hygienic working environment where adequate steps have been taken to prevent fire related, machine and safety accidents. Workers receive regular and recorded health and safety training, and this training will be repeated for new or reassigned workers. We also mandate that workers should have access to clean toilet facilities and to potable water, and, if appropriate, sanitary facilities for food storage shall be provided. Accommodation, where provided, should be clean, safe, and meet the basic needs of the workers.

Q: What are some of the challenges of implementing this in Bangladesh? Dani:Hartals occur relatively regularly and sometimes are violent; roads are often blocked off which can mean that certain parts of the capital can get cut off. This is difficult not just for F&F and our employees in Dhaka, but also for the factories. Products and materials that need to be received by the factories in order for their workforce to make an order can be delayed. The workforce whose role it is to make the product could be sitting and waiting for deliveries to arrive for days and this can ultimately lead to longer working days, when they finally arrive. Factory training programmes, meetings and visits – no matter how important – must be put on hold and rescheduled.

We have also be working to help some factory owners understand that cutting corners doesn’t make sense in the long run. The short term gain of not providing workers with basic safety equipment is likely to have a long-term detrimental effect on their business and workers and just doesn’t make sense. It has also been a challenge for them to see us and the BBW as part of the process and fellow collaborators and not just seen as external people in their factory. In some cases it has been a more effective process to empower the workforce to initiate change with some factory owners.

Q: As documented in The True Cost movie, there is clearly an issue in Bangladesh of workers not having the right to collective bargaining with factory owners. How does Tesco use their influence on factory owners to persuade them it is worth their while improving conditions for the workers? Mashuda: Tesco requires that all factories that we use in Bangladesh must have a Workers Participatory Committee formed through an election process, to ensure the workers’ rights and benefits. During our regular audits we monitor whether this has been in place and it is viewed as a violation of law if the factory doesn’t comply, which we follow up until this criteria has been met.

Q: What social enterprise work are you doing in Bangladesh? Dani: Studies have shown that children, in the developing world, who go to school in uniform perform better in tests and have lower rates of absenteeism. This year we are donating 20,000 school uniforms in Bangladesh as part of our Buy One, Give One scheme. When a customer buys an item from the Buy One, Give One range we will donate an entire uniform. So as our polo shirts are made in Bangladesh for every pack bought we donate a uniform to a child there.

Please click here for more information.

Tesco Clothing Corporate Responsibility

The True Cost Movie – www.truecostmovie.com

#whomademyclothes? – www.fashionrevolution.org

Project BBW – www.impacttlimited.com

All photos used with permission of Tesco.

Blog kindly reproduced with permission from N4Mummy