MASS CONSUMPTION: THE END OF AN ERA?

On Friday 24th April 2020, Fashion Revolution hosted our sixth annual Fashion Question Time, a powerful platform to debate the future of the fashion industry during Fashion Revolution Week. In light of current COVID-19 measures, Fashion Question Time was hosted in a new digital format.

This year’s theme, “Mass consumption: The end of an era?”, couldn’t feel more relevant to the present situation. Our current crisis has sparked a renewed desire to support each other in a time of uncertainty and is highlighting ways in which our personal habits can become more sustainable. We have been encouraging an end to overconsumption for many years, yet we also know that in the face of this unexpected halt in manufacturing, it is the most vulnerable, lowest paid people in the fashion supply chain that feel the worst effects. So, as we take this time to pause and reflect on our own consumption and disposal patterns, the question of how to support the millions of supply chain workers who have already lost their jobs remains largely unanswered.

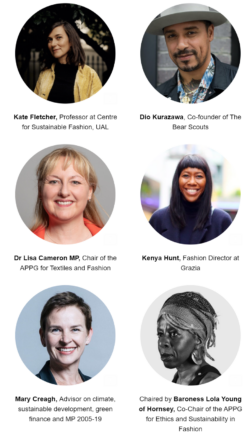

MEET THE PANEL

MISSED THE EVENT? WATCH FASHION QUESTION TIME AGAIN HERE:

Below we have selected some questions and answers that were discussed over the debate during Fashion Question Time 2020:

An opening speech was made by Carry Somers, co-founder and Global Operations Director of Fashion Revolution, speaking of her recent voyage in the Pacific researching microplastics, she said:

And there in the middle of the ocean, I confronted the signs and symbols of our consumption, across the pacific seascape. I witnessed the reflection of our age of excess in the surface of the sea, in the trail of plastic waste which has been left in the wake of uncontrolled growth. So our challenge this decade is to move beyond our currently destructive and western world view which is tipping us into a climate catastrophe and a plastic pollution crisis, towards a fashion industry that integrates nature in a truly sustainable way.

The first question was submitted by Edwina Ehrman, Senior Curator at the V&A, focussed on how clothing demand may change post-COVID.

Kenya Hunt, Fashion Director, Grazia:

We’re already seeing a change in demand and I think that largely boils down to the economy which is in a state of free fall. I read that 75% of consumers in Europe and the States, believe that their personal finances are being negatively impacted by this pandemic. So that alone is, it is impacting demand. On top of that, we were seeing a gradual shift and mindset with consumers in general as awareness spreads of how overconsumption has a negative toll on the planet.

Mary Creagh, Advisor on climate, sustainable development, green finance and MP 2005-19:

I think there’s a radical change coming – we’ve seen collapses in sales. I’m sure China is seeing a boom but that’s because nobody’s bought anything that for three months. So what happens when the sort of pent up demand, the people who want those handbags or want those top items? What happens when they stopped buying those things? They’ve got what they want. What’s clear is there’s a collapse in sales, an absolute collapse.

The following question by Sarah Mower MBE explored current reduction in growth and its impacts on garment workers.

Kate Fletcher, Centre for Sustainable Fashion, UAL:

De-growth is not the same as negative growth. And what we’re experiencing at the moment is negative growth. And I think it’s really wholly wrong to assume that what is happening now in the fashion sector in any way gives us a full taste of what will happen if we engage with de-growth ideas fully. So what growth is, is it’s the process of accumulation of capital and wealth. Whereas de-growth by contrast, it’s not an economic concept wholly. It really involves the whole of society. It asks questions about values and representations and it’s about examining consumption of natural resources and energy but within the carrying capacity of the planet.

Dr Lisa Cameron MP and Chair of the APPG for Textiles and Fashion:

There are massive global issues to consider in terms of appropriate wages for those workers internationally and how we’ll attempt to support them in when they are in poverty. There are also issues for the UK in terms of the fashion industry to take forward, which have been thrown into this conversation and we’re looking at trying to address some of those. That might be something that that moves forward progressively as a result [of this pandemic].

Celine Seeman, Founder of Slow Factory, submitted a thought-provoking question on how we can reconcile the current business model dependent on consumption.

Dio Kurazawa, Cofounder, The Bear Scouts:

This is about capitalism. And I think it’s very key to note that she said that this is rooted in insecurity. Yes. that’s correct. We don’t need to buy all the things that we do buy. But these businesses have been set up in order to perpetuate overconsumption. I think the real answer to this is really innovation. It’s about how things are made. Are they adopting circular methods? The other thing is that brands don’t look at their supply chain as partners. A lot of my manufacturing clients have been left in the dark by Arcadia group, for example, who’s left one of my manufacturers with a bill of around 400,000 pounds in cancelled orders.

Kate Fletcher, Centre for Sustainable Fashion, UAL:

The fashion industry has been set up to make us spend money we don’t have on things we don’t need to impress people we don’t much care about. And so as we’re going forward, it is important for us to, to recognize that the business model that underpins the current fashion sector is based on a logic of economic growth. Other logics and other business models are available. It’s not the only world, we created this and we can create something else. We need business as part of a solution moving forward.

The next question by Catherine Teatum, Creative Director at Teatum Jones, focussed on educating the next generation.

Kate Fletcher, Centre for Sustainable Fashion, UAL:

The education of this group is mainly currently handled by the marketing departments of brands. And this is really shocking, isn’t it? The economic growth focus that’s so prevalent in society means that consumption really isn’t critically considered in schools and across the curriculum. There isn’t a coherent critique of what consumption practices mean in the school curriculum in the UK at all.

Dio Kurazawa, Cofounder, The Bear Scouts:

I think it’s really about coming together and working with a variety of folks who may not be embracing responsible fashion or climate change, but maybe they have the platform that prevails for that demographic. I think we need to work together across industries in order to get this message across.

Mary Creagh, Advisor on climate, sustainable development, green finance and MP 2005-19:

I think this virus is an opportunity for us to sit at home and talk about how we learn and what we learnt. And when we had our inquiry, we had a lecturer from Leeds College of Fashion who said, ‘one of my students said I’m going to have to go and get a new coat because the buttons come off this one’. The fact that you’ve got fashion students, and I’m not saying this is universal but it was anecdotal evidence, that can’t sew on a button. When 20 years earlier, you have 11 year olds that can do blanket stitch and chain stitch. Once you’ve made something and sweated over it for hours, you’re much more likely to throw it out because you actually understand the making and creation that went into it.

Caroline Lucas, MP for Brighton Pavillion and former leader of the Green Party, asked what a world could look like if we moved away from consumption to a model of sufficiency.

Mary Creagh, Advisor on climate, sustainable development, green finance and MP 2005-19:

How do brands in fashion 2.0 make deeper relationships? They know their staff here in this country. Why can’t they know their staff in Bangladesh, in China? And why can’t they look after them in the way that they look after their workers here? And if you go back to Salts Mill and Salter or Bournville for Cadbury’s, some of those great industrialists realised their workers were living in awful conditions and created model villages for them. I think there’s something there about knowing your workers better.

Dio Kurazawa, Cofounder, The Bear Scouts:

We just now have a new launch of a new innovation that allows you to feel the fabric of a garment just through your mobile phone. So there are a lot of innovations that are out there. The problem is fast fashion won’t pay for it because the model of the fast fashion is built on does not allow for such a thing. It’s based on spending little but having a big margin to sell in order to get a profit. And until that shifts, until you can regulate, at least the businesses within the UK who are going way over to the far East in order to take advantage of these lower prices, then we’re never really going to get anywhere.

A question from Josie and Rich, Adapt Climate Club, explored how we can change attitudes of consumers and policymakers.

Kenya Hunt, Fashion Director, Grazia:

I work on the B2C side of things, so I’m always speaking to the consumer at the magazine. I think it’s about just really constantly showing them how their habits really impact one’s day to day life. I was talking to the designer Bethany Williams and she was saying that if people knew that when you order multiple sizes and you keep one and you send the others back that they may be burned, that they probably wouldn’t do it. So, I think educating them essentially to the high cost, the very high cost of cheap clothing, should be number one.

Dr Lisa Cameron MP and Chair of the APPG for Textiles and Fashion:

We need to make it more obvious for consumers, perhaps like a traffic light system of green, amber and red in relation to different aspects of manufacturing. There’s some resistance obviously from the industry itself. So, I think it’s going to be a combination of shifting our education for young people to make sure that they understand the global goals, the sustainable development goals, by combining that with some regulation.

Orsola de Castro, co-founder of Fashion Revolution closed Fashion Question Time with a speech:

We will have to look for balance after all this. Let’s ensure this period of restrictions won’t be followed by one of hyper excesses, of business as usual times 10. There are ways to make an adequate amount of products, providing dignified work to the people who make them, while protecting and conserving our environment – we have to invest in them and implement them with rigour. So the call to action from this FQT couldn’t be more simple. Go back to the event’s title: Mass consumption – the end of an era? And the remove the question mark. Mass consumption – the end of an era. FULL STOP.

We are so grateful to Baroness Lola Young of Hornsey for chairing our first *virtual* Fashion Question Time event, and to our brilliant panellists, Mary Creagh, Kenya Hunt, Dr Lisa Cameron MP, Kate Fletcher and Dio Kurazawa. In addition, we would like to thank Edwina Ehrman and the team at the V&A for their continued support despite the circumstances.

At the G7 Summit, which wrapped up in Biarritz earlier this week, climate change was a central focus. On the 24th of August, just ahead of the summit, President Macron, along with 32 major fashion brands revealed the Fashion Pact, an industry wide movement aimed at aligning the fashion industry with the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

If you haven’t read the Pact, which we recommend doing, here’s what you need to know:

- The Pact is a series of commitments based on Science-Based Targets (SBTs).

- The Pact is aiming to be adopted by 20% of the global fashion industry

- The 32 signatories include:

- Adidas

- Burberry

- Chanel

- H&M

- Gap

- Inditex (Zara, Pull & Bear, Bershka, etc)

- Nike

- Nordstrom

- Prada

- Kering (Gucci, Yves St Laurent, Balenciaga, etc)

- Puma

- PVH (Calvin Klein, Tommy Hilfiger, etc)

- Stella McCartney

- The focus is on 3 pillars: Climate, Biodiversity, and Oceans

- Commitments include already existing initiatives like the UNFCCC’s Fashion Charter (of which Fashion Revolution is a signatory), alongside numerical targets like brands reaching 100% renewable energy in their own operations by 2030

Below, we hear from 3 experts across our global coordination team to find out what this Pact means for the industry, and what’s missing…

Science-Based Targets

Orsola de Castro, Co-founder: Holding fashion brands to Science-Based Targets is incredibly important for industry change. It removes the wiggle room potential of many broad and ambiguous commitments we’ve seen up until now.

Sienna Somers, Policy & Research Coordinator: SBTs for greenhouse gases are based on a given brand’s size and turnover, they must set targets to reduce their footprint in line with the 1.5-degree pathway demanded by the International Panel on Climate Change. These are pretty commonplace within the industry now and are comparable from one brand to another. However, most of the SBTs in the fashion industry are focused on the companies own operations and are not looking at the emission at the raw material level, which is where we know the majority of brands’ impact comes from. We need to see brands set targets and incentives from their raw material suppliers and through the rest of the supply chain. I am very pleased to see the addition of developing SBTs for biodiversity, this is something that is sorely needed, especially at the raw material level.

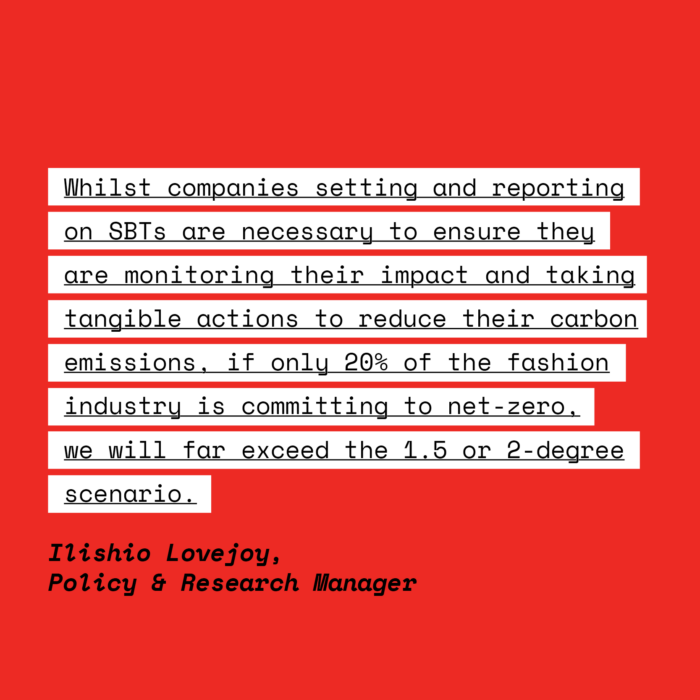

Ilishio Lovejoy, Policy & Research Manager: The Fashion Transparency Index has worked for years to push for more credible, comprehensive and comparable public disclosure of businesses’ commitments, practises and, importantly, impacts. Whilst companies setting and reporting on SBTs are necessary to ensure they are monitoring their impact and taking tangible actions to reduce their carbon emissions, if only 20% of the fashion industry is committing to net-zero, we will far exceed the 1.5 or 2-degree scenario. In contrast, the UNFCCC’s Fashion Industry Charter aims for at least 50% of the fashion industry to join, and targets not only fashion brands but media outlets, industry associations, governments and NGOs.

Collaboration over Competition

With “20% industry adoption of the Pact”, the question remains: what about everyone else?

Ilishio Lovejoy: We need to see significantly more than 20% of the global fashion industry (measured by volume of products) working together to achieve the systemic change that is necessary.

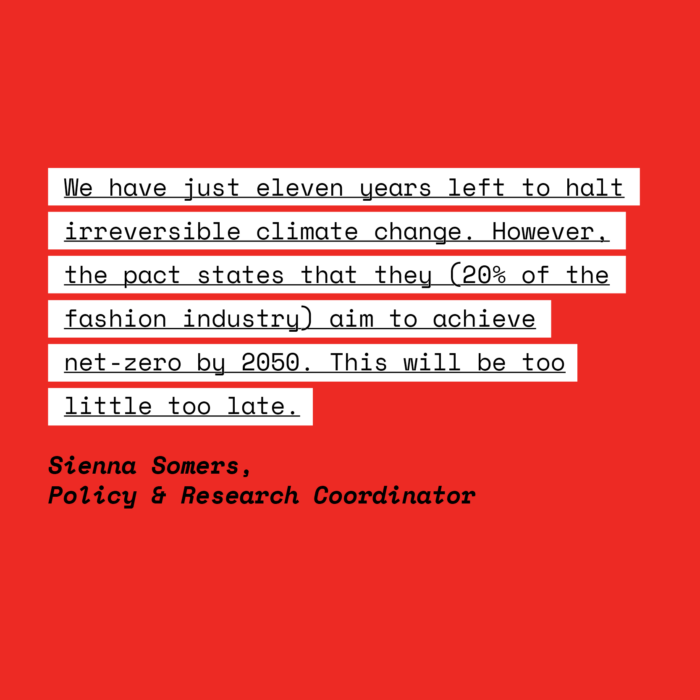

Sienna Somers: We have just eleven years left to halt irreversible climate change. However, the pact states that they (20% of the fashion industry) aim to achieve net-zero by 2050. This will be too little too late. In addition, SBTs assume everyone is essentially doing their ‘fair share’. Yet if the remaining 80% of the industry is not making progress towards tackling climate change, these actions will not be enough.

Orsola de Castro: If this 20% was made up of brands that had never made strides towards sustainability, then this would be something worth celebrating. But the fact that many of the brands, like Kering and Stella McCartney have been vocal about their environmental goals for years means that this is nothing new. Kering has been telling us they are the most sustainable luxury brand possible for the past five years, yet only now they’re signing onto these targets – what have they been doing this whole time?

Most notably missing from the list of signatories is LVMH group (Which owns Louis Vuitton, Dior, Kenzo, and dozens more luxury houses). As Kering’s biggest competitor, LVMH’s absence is a classic example of the anti-collaboration mentality that hinders sustainable innovation in the fashion industry. In a climate emergency we need collaboration over competition.

Change, NOW

While the Pact is focused on tomorrow, via its non-obligatory targets, we need action today.

Ilishio Lovejoy: The pact calls for, “Eliminating the use of single use plastics (in both B2B and B2C packaging) by 2030”. We need to see action being taken now, not by 2030. There is no longer an excuse to use virgin plastics when there are so many recycled alternatives available.

Orsola de Castro: 2030 is ridiculous – we could all be dead by then! We need a ban on single-use plastics NOW.

The Pact states, “Each member company may choose appropriate courses of action from the possibilities listed as examples below each commitment, to achieve the objectives defined in the Pact”.

Sienna Somers: Essentially, this is saying that the contents of the Pact are non-binding or non-obligatory, merely suggestions. We, as citizens, need to hold brands accountable to their commitments, otherwise, these statements, pacts and charters are simply greenwashing. We also need to demand legislation to hold these brands (and the brands doing nothing at all) to account, as this kind of non-binding protocol lets the industry-self regulate. It’s a reminder of the UK’s Environmental Audit Committee report on fashion, which pointed out that, “the fashion industry has marked its own homework for too long. Voluntary corporate social responsibility initiatives have failed significantly to improve pay and working conditions or reduce waste.”

The Elephant in the Room

Hint: It’s overproduction.

Orsola de Castro: This Pact is Copenhagen [Fashion Summit] all over again – the same people saying the same things.

Ilishio Lovejoy: We need to see more focus on the issue of overproduction as a key driver of the global climate emergency.

Orsola de Castro: Brands don’t want to talk about overproduction, but this is no longer acceptable. If we are to address climate change, fashion needs to slow down. We must divest in growth to invest in supply chain prosperity.

Sienna Somers: The bottom line is that these brands are only going to do what in their interest and what doesn’t impact profit. We need to make these issues a priority for brands and show them that if they don’t start taking action, then we will no longer support them. Once it impacts their profit, that’s when they’ll listen.

*banner image is from QUARTZY*

On Monday 29 June 2015 in the UK House of Lords, industry leaders, press and political leaders attended the roundtable debate Ethical Fashion 2020: a New Vision for Transparency. The aim of the event was to help to shape a vison of what transparent supply chains could look like in five years time and set out what steps are needed to transform the fashion industry of the future.

The event at the House of Lords, now in its second year, was co-hosted by Fashion Revolution, the Institution of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH) and the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Ethics and Sustainability in Fashion.

Introducing the event, IOSH Chief Executive Jan Chmiel said

“Transparency matters because it can drive improved workplace standards. It can also increase recognition of good health and safety performance. And importantly, it can help ensure more people view health and safety as an investment, not a cost – one that saves lives, supports business and sustains communities. Whereas, a lack of transparency can do the reverse. Crucially, it can mean that firms don’t know the factories that are supplying them, so they can’t actively manage their risks – potentially leading to tragedy, disaster and business failure”.

Co-founder of Fashion Revolution, Carry Somers, set the scene as to why transparency is a crucial issue to address over the next 5 years

“So much is hidden within the industry, largely because of its scale and complexity. The system in which the fashion and textiles industry operates has become unmanageable and almost nobody has a clear picture how it all really works, from fibre through to final product, use and disposal.

The low or non-existent levels of visibility across the supply chain highlight the problematic and complex nature of the fashion industry. A few brands have received a lot of public pressure to publish information about their suppliers and some have responded by disclosing parts of it. Yet, the rest of the industry remains very opaque. It’s not just brands; it’s the myriad other stakeholders along the chain too. We believe that knowing who made our clothes is the first step in transforming the fashion industry”.

The two hour debate, chaired by Lucy Siegle, acknowledged where progress needed to be made, highlighted opportunities for change and set out a vision for how the fashion industry could and should look by 2020.

Some of the key points made by the speakers are set out below:

Peter McAllister, Executive Director of the Ethical Trading Initiative

- We need to break down what transparency looks like and define what the journey looks like, so we get a virtuous circle.

- Smart regulation drives behaviour. Once the environment is predictable, business can work within that environment. What is difficult is when business can’t predict when wages will rise or fall, when there will be a strike, etc.

- We need mechanisms where workers are represented not where they are just at the receiving end of good intentions

- We want to see the UN Guiding Principles on Human Rights become a rallying call to transform fashion industry and see this fully implemented by 2020. Companies need to undertake human rights due diligence, understand the impacts and take the remedial action required. This underpins the need for transparency.

- We can’t wait for a crisis – we need to put national and private mechanisms in place. We need to set up platforms in key places such as China and India to influence change in producer countries.

- Bangladesh is still a young country with weak infrastructure. The Accord and the Alliance were the right response at the right time. It is an attempt to turbocharge the effort of the Bangladesh government to set up their own mechanisms. It is designed to be a contribution to a longer term shift, of which we are yet to see the green shoots.

- Transparency is coming at companies, whether they like it or not – better to get ahead of the curve. The best way to get change is to inspire competition between companies.

- This sector is well overdue transformative change, not just twiddling at the edges

Rob Wayss – Executive Director of The Bangladesh Accord

- Accord signatories were placing “unprecedented” requirements on their suppliers.

- Even though there had been a positive response to the Accord, much more needs to be done including the increasing the pace of remediation works in factories and ensuring workers are able to raise safety concerns without fear of reprisal. If other workers see that raising safety concerns leads to hassle, they won’t express worries themselves.

- The Accord is based on a 5 year agreement. Health and Safety Committees have been put in place in all factories, remedial action is being taken, factories are working with union representatives.

- Transparency is the key to progress and the way the Accord works. We publish inspection and disclose non-compliance.

- Inspections for the Accord were carried out by world class engineers who worked alongside Bangladeshi engineers. I would like to see the assessments based on scientific engineering principles.

- Money, resources and political will are needed to change the way we do business.

- A kite mark on garments to verify ethical production would be very difficult as would need to verify what is the standard, who is assessing and monitoring. It is very high risk and it is not very meaningful, even though there is an appetite for this amongst consumers.

- The media has an important role to play as it creates pressure. Where there are legitimate article expressing valid criticisms, we respond accordingly. However, some articles in the Bangladeshi press were perhaps generated by factory owners who wanted to see the pace of the Accord slowed down.

Baroness Young of Hornsey – All-Party Parliamentary Group on Ethics and Sustainability in Fashion.

- You can only make a choice if you have information and that information turns to knowledge

- More businesses need to be more honest.

- We need to think more creatively and outside of the box of usual business models.

- Legislation won’t solve the whole problem but it can promote cultural change, as we’ve seen with the Equality Act.

- The government had to be encouraged to put the transparency clause in the Modern Slavery Bill in place by business. Loopholes in law which still exist around Modern Slavery Act will be stricter by 2020.

- The fashion industry is different to other industries as it has such a widely distributed supply chain. I’d like to see pressure building so companies can make progress on their public statements over the next five years as to how they are addressing modern slavery within their supply chains.

- We need more empowerment of consumers, business and politicians so this becomes so much part of life that we don’t need to think about it.

- The idea of a kite mark on the surface seems attractive but it simplifies what is an incredibly comples area. How do you make calculations which balance the social and the environmental?

- We can’t assume Made in Britain is OK. One member of the APPG saw conditions in a garment factory in East London last week as bad as those you would see anywhere in the world.

Simon Ward – British Fashion Council (BFC)

- The BFC has a three-year strategy to put sustainability at the heart of all we do. BFC is undertaking a collaboration with Marks and Spencer through the Positive Fashion initiative to promote best practice in order to stimulate real and meaningful change, highlighting the practical toolkit for designers which incorporates sustainability.

- There is a a need to find creative solutions and look at things differently. For instance, the BFC worked with the government to set up a draft standard on fashion apprenticeships as a solution to the problem of unpaid interns.

- We’re on an endless hamster wheel, more & more, cheaper & cheaper. How can we break the madness & tell a positive, creative story? People warm to the story and telling the story behind an item of clothin is an entrancing way to give insight into the people behind the clothes. It provides a compelling motivation for change.

Garrett Brown of the Maquiladora Health and Safety Support Network

- We need public listing of supply chains

- We need public disclosure of monitoring timelines and remedial action

- We need meaningful participation by workers, including training to give them the information and authority to act without retaliation.

- Sourcing is currently driven by the lowest price, highest quality, fastest delivery, with a window dressing of CSR.

- It is a pre-requisite that governments have the will and the resources to enforce the regulations, but in most places in the developing world this isn’t the case. In Bangladesh, it should be the government enforcing regulation and the Accord is a real step towards achieving this. Mexico has strong health and safety legislation, as strong as the US, but it has high foreigh debt, so won’t do anything to deter investents. This is why workers need to protect themselves.

- Transparency is only as good as the information that you get

Finally, Lucy Siegle asked the panellists what one thing would make a massive difference by 2020?

Garrett Brown: The Accord model of public discoloure is critical. Brands have to disclose where their factories are and tell us about the conditions.

Simon Ward: A lot of big and complex change is required. We need a magic story to tie it all together so it is understandable.

Baroness Lola Young: Information leading to activism. Supporting organisations like Fashion Revolution which are build on the work of other organisation like the EFF, ETI, Labour Behind the Label. Information needs to be acted on and we need coalitions like Fashion Revolution which can lobby for change.

Rob Wyass: Audits, credibly performed

Peter McAllister: The ETI has made a commitment to develop a public form of the audits of their companies which we hope will showcase some of the best performers.

After the debate, guests adjourned to River Room, overlooking the Thames, for a drinks reception and networking. Baroness Lola Young and Lord Speaker, Frances de Souza, both gave speeches at the reception and many of the guests were filmed for an upcoming series of mini films being produced and directed by Fashion Revolution as part of the European Year for Development.

The event at the House of Lords brought together many of the key people from within the fashion industry and beyond who are at the forefront of creating meaningful change. The challenge now is to translate the vision set out for transparency in 2020 into a reality in order to transform the fashion industry of the future.

Photo credits: Arthur & Henry, Zoe Hitchen, Orsola de Castro and IOSH