Este 17 al 24 de abril en Guadalajara, Jalisco estará sucediendo algo único!

Este 17 al 24 de abril en Guadalajara, Jalisco estará sucediendo algo único!

Te invitamos a vivir un evento multisede, en el cual podrás conocer de distintas maneras, cómo se puede ser parte de la revolución de la moda, esta de la que tanto se habla y a veces creemos que es totalmente ajena a los que no son diseñadores o marcas de moda.

En este evento conmemorativo por los 10 años de nuestro movimiento, podrás descubrir lo fácil que es ser parte, sin saber nada de diseño o del mundo del fashionismo.

Descubre aquí todas las actividades día por día , y por si quedara alguna duda, puedes seguirnos en Instagram y Facebook, donde estaremos compartiendo todos los detalles de esta increíble semana.

Día 1 – Miércoles 17 de Abril

- Inaguración 4:00 pm

Comenzaremos la semana de actividades con una colaboración irrepetible en Ciudad Creativa Digital:

Además del corte de listón te compartiremos todos los detalles sobre el evento, las sedes, los ponentes y todas las sorpresas que te esperan por ser parte de la Revolución!

- Conferencia: Introducción a la Moda Ética 5:00 pm Una de las marcas pioneras en sustentabilidad en México: C&A, nos acompañará para darnos una introducción a este tema, tan sonado como controversial.

- Conferencia: Fashion Tech 6:30 pm

De la mano de la líder en Tecnologías relacionadas a la sustentabilidad en Jalisco: Elizabeth Salim.

Pregunta por el Auditorio de la planta baja

¡Evento gratuito! ¡Registrate en

Mapa para llegar

Día 2 – Jueves 18 de Abril

Panel: Moda en evolución, género e igualdad 1:00 pm

Nuestros amigos de Igualdad Sustantiva Jalisco nos ayudarán a crear un espacio donde se pueda poner sobre la mesa el cómo la moda tiene una influencia en las nuevas y no tan nuevas perspectivas de género en Jalisco y en el mundo. Y lo mejor, en uno de los recintos mas cool de la Ciudad: el ExConvento del Carmen (pregunta por la Sala Higinio Ruvalcava)

¡Evento gratuito! ¡Registrate en

Mapa para llegar

Panel: El futuro de la moda y su impacto – 7:00 pm

Un grupo de mujeres emprendedoras y pioneras en la Moda sustentable, nos hablarán, desde distintas trincheras, sobre las últimas tendencias y la relación de este tema que tanto suena últimamente con temas como la cultura, el medio ambiente y la circularidad en la zona mas cool de la ciudad a unas cuadras de Avenida Chapultepec!

¡Evento gratuito! ¡Registrate en

Mapa para llegar

Día 3. – Viernes 19 de Abril

Conferencia: Transparencia entre las marcas de moda mexicanas con Efrain Paulino. 1:00pm

El ex coordinador de Fashion Revolution México y experto en Transparencia en la moda, dará la oportunidad a toda la comunidad ITESO para conocer cómo es que se puede ser tener prácticas más transparentes, así como usar eso a su favor en la hora de posicionar y promocionar una marca. Aunque es un evento dentro de la universidad, está abierto a todo Público. No olvides pedir tu QR de acceso al ITESO, enviando tu registro de Event Brite al Instagram de Modas Iteso.

Pregunta por el Auditorio 405 y 406 del Edificio W

¡Evento gratuito! ¡Registrate en

Mapa para llegar

Día 3. – Viernes 19 de Abril

Taller | Bordado artivista con Colectivo Zurciendo al Planeta 4:00pm

Zurciendo el Planeta es una colectiva artivista, que organiza eventos de Activismo ecológico mediante el bordado, y en el marco de nuestra FRW abrirá sus puertas para compartir toda su experiencia e invitar a hacer Artivismo, una actividad clave para ser Revolucionario, así que no te la pierdas!

Será en la terraza del piso 4 de la Biblioteca UDG!

¡Evento gratuito! ¡Registrate en

Mapa para llegar

Día 3. – Viernes 19 de Abril

Charla : Consumo de moda responsable (y local) 6:00pm

Dos mujeres con proyectos que, desde su propia perspectiva profesional sobre la Sustentabilidad: Athziri Magaña de Biosis Lab y Achtli Bautista de Ach+ , nos compartirán el sin fin de posibilidades que existen para que , aún sin ser diseñador ni estudiante de moda, podamos adquirir hábitos y formas de consumir más responsables. Si quieres ahondar en el mundo de la moda Eco, no te la puedes perder!

Pregunta por el Auditorio de la planta baja.

Evento gratuito! ¡Registrate en

Mapa para llegar

Día 3. – Viernes 19 de Abril

Taller : Estilo personal sostenible con Go Trendier – 6:45 pm

Go Trendier! la plataforma número uno de ventas de Segunda Mano, se suma a nuestro cartel de eventos para impartir un taller que te ayudará a construir tu propio guardaropa de una manera más sostenible, entendiendo desde la raíz el concepto de Circularidad y su experiencia como negocio y pioneros en innovación.

Pregunta por el Aula conectar inovar Piso 3 – 301

Evento gratuito! ¡Registrate en

Mapa para llegar

Día 4. – Sábado 20 de Abril

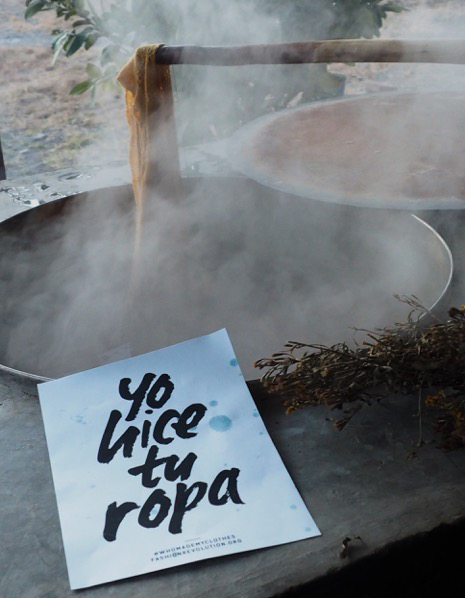

Panel : Teñido con azul natural: alga espirulina- con Efrain Paulino – 10:00 am

El azul es uno de los colores más bellos, sobre todo por que nos recuerda a la tierra, te imaginas teñir la moda con azul natural? cómo, con qué elementos y sobre qué superficies? descúbrelo todo de la mano de este grupo de académicos que están investigando como trabajar con el alga espirulina para encontrar distintas tonalidades de este bello color.

Agradecemos a las Secretarías de Medio ambiente y Desarrollo Económico por darnos este espacio en la colonia más cool del mundo!

(Pregunta por la Sala por confirmar)

Evento gratuito! ¡Registrate en

Mapa para llegar

Día 4. – Sábado 20 de Abril

¡Talleres de Moda Sustentable para toda la famila! – 11:30 am

Upcycling: renovación consciente para niños Enfoque niños 5-9 años acompañados de un adulto. Con Achtli Bautista – Aprende a darle nueva vida a tus prendas en familia y de una manera fácil y circular, desde el toque de una de las marcas de Upcycling más originales en Jalisco: Ach +.

Costo de recuperación de $80 pesos

Remiendo visible – Dora Moro (adultos) de TejeDora – Aprende a bordar y elegir los diseños más adecuados para tus prendas , de la mano de una de las pioneras en arte textil y una talentosísima maestra.

Aportacion voluntaria. Llevar una prenda rota o manchada para reparar con bordado

Colores naturales para mi ropa para adolescentes de Enfoque niños 9 años en adelante, con Athziri Magaña – Conoce formas de teñir tu ropa de la manera más original y sustentable, con elementos naturales que además puedes conseguir fácilmente en nuestro país, de la mano de Athziri, quien trabaja de la mano de artesanas.

Los asistentes deben llevar una playera de algodón que deseen teñir.

Costo de recuperación de $100 pesos

Evento con costo de recuperación

Registrate en

Mapa para llegar

Día 5. – Domingo 21 de Abril

Panel : Somos la revolución – con las voluntades de Fashion Revolution México. – 11:00 am

Conoce nuestro movimiento, y cada paso que hemos dado desde su nacimiento en el sur del país y cómo lo ha ido recorriendo hasta llegar con esta propuesta de evento a Guadalajara, además de conocer qué se viene en un futuro para la moda sustentable en nuestro país!

(Pregunta por la Sala por confirmar)

Evento gratuito! ¡Registrate en

Mapa para llegar

Día 6. – Miércoles 24 de Abril

Pasarela de Clausura: Yo hice tu ropa 6:00 pm

Gracias a Bajío Moda por compartir su filosofía de trabajo, inspirándonos a organizar esta Pasarela al aire libre y de acceso a todo público, justamente para acercar el mensaje de que la moda es para todxs, acompáñanos en la Rambla Cataluña (Av. Juarez en medio de de la rectoría de UDG y el Templo Expiatorio ).

The Maya Youth Artisanship Initiative has been set up by textile artist Angela Damman to teach a new generation of artisans how to work with the fibre extracted from a species of agave indigenous to Yucatán, México: henequen.

One hundred years ago, 70% of all cultivated land in the Yucatán was used to grow henequen and it once accounted for 90% of all ropes in the world, but the advent of synthetic fibres led to a steep decline in cultivation and in the skills used to create this strong, versatile fibre.

As a result, the craft of spinning and weaving with this endemic plant fibre almost became a lost textile art as the artisans who possessed the skill grew old and young people were reluctant to learn this traditional skill.

The young women of this region have been brought up in communities where they are marginalised in every aspect of their lives: they are indigenous women, poor, living in rural communities and speaking Maya. The initiative aims to reverse this sentiment by transforming these into positive attributes, showing them that being Maya, a weaver and living in a rural area with a rich cultural heritage is a pathway to opportunity.

The pilot, in collaboration with Ashley Kubley, assistant professor, University of Cincinnati, aims to preserve the technique of working with henequen and elevate it from the utilitarian to create fine artisanal products such as bags which use new patterns, woven on backstrap looms and using natural dyes. Collaborating with the local community, the practice of weaving is now being transmitted from the teachers to the students, women 29 and under.

By bridging the generational gap through the transmission of skills, the craft is being demystified and destigmatised for the young women. The hope is that this will allow a new generation to develop the industry and see the art of weaving plant fibres as a design vocation. Participation in the luxury artisan handicraft market will enable them to keep alive the ancient knowledge of their ancestors, leading to a new appreciation for their Mayan identity and the regeneration of rural economies. This truly is sustainable development.

Text and Images: Carry Somers.

Weaving image: Angela Damman

Microfinance is based on the philosophy that even very small amounts of credit can help end the cycle of poverty. 70% of the world’s poor are women, and 80% of the world’s garment workers are women. Microfinance organisations typically lend to women, not only because they are considered a good investment as they are more likely to repay their loans, but also because lending to women brings with it a raft of social benefits for the women, their families and the wider community.

Microcredit has its advocates and its critics. Fashion Revolution will shortly be embarking on a year-long project in collaboration with MFO, Micro Finance Opportunities, and BRAC. In preparation for our work, I started to read more about microfinance and I also booked a tour with Envia in Oaxaca, Mexico so I could hear stories directly from the beneficiaries of microloans.

Advocates of microfinance include former Chief Economist at the World Bank, Joseph Stiglitz, author of Making Globalisation Work. Stiglitz sets out the importance of community involvement in development projects. He says that the microfinance model pioneered by Grameen in Bangladesh is successful because it addresses the needs of the communities which it serves. Their loan schemes work because groups of women take responsibility for each other and support one another in the loan repayment process.

But microfinance has its critics as well. Ha-Joon Chang, author of 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism says ‘If effective entrepreneurship ever was a purely individual thing, it has stopped being so at least for the last century. The collective ability to build and manage effective organizations and institutions is now far more important than the drives or even the talents of a nation’s individual members in determining its prosperity. Unless we reject the myth of heroic individual entrepreneurs and help them build institutions and organizations of collective entrepreneurship, we will never see the poor counties grow out of poverty on a sustainable basis.’

Chang illustrates the problem with an example of a Croatian farmer who buys a cow on microcredit. This farmer has to sell the milk from the cow, even if the bottom is falling out of the local milk market and prices are plummeting because hundreds of other farmers have taken out loans and are selling more milk. It is impossible for the farmer to turn himself into an exporter of butter or cheese as they don’t have the technology, organisational skills or capital. ‘What makes rich countries rich is their ability to channel the individual entrepreneurial energy into collective entrepreneurship’ says Chang.

Looking specifically at the Mexican context, a study by Poverty Action Lab into the impact of microcredit for women in Mexico found that microcredit increased access to formal financial services which helped businesses to manage their cash flow and enabled some existing businesses to expand. However, it did not increase household income, business profitability or prompt new business creation. It was found that most of the loans made by microfinance organisations were used to make up for a shortfall in income due to unexpected circumstances such as weddings, or the need to buy medicine for a family member.

I realised quite early on in my research that not all microfinance organisations are set up as not-for-profits. Microfinance is big business in Mexico.

Institutions which started out providing affordable credit to the poor have burgeoned into large commercial institutions. The average interest rate for a microloan in Mexico is 74%, with many loans incurring 200% interest per annum. It’s no wonder that 28% of microfinance borrowers in Mexico hold over 4 loans, and 11% hold over 6 loans, often all with different microfinance institutions. Instead of helping to raise borrowers out of poverty, these loans plunge them into a spiral of debt, from which the only temporary relief is another loan to pay off the existing loans. These rates are partly the result of the decentralised nature of microcredit lending, but institutions also argue that it is because of the high risk of lending to people with no credit history.

But, are the rural poor such a high risk? Joseph Stiglitz says that Grameen Bank in Bangladesh who give small loans to rural women found they had a far higher repayment rate than rich urban borrowers.

Before visiting the Zapotec community of San Miguel del Valle to meet the recipients of microloans, I asked Envia more about how they operate and what interest rate they are charging to their borrowers.

Envia was founded in 2010 and is currently run by four staff and a team of volunteers. Envia’s model is to provide interest-free loans which are funded through responsible tourism, such as the tour I took to meet the loan recipients. Envia’s tours are, in fact, the no.1 excursion in Oaxaca on Tripadvisor and certainly provide an authentic experience, as well as a unique insight the life and work of rural Zapotec women.

100% of the money raised from tours is put towards loans. Once this is repaid, the money is used for a second round of loans, and finally a third round of loans, education programmes and salaries. So the income from the tours is effectively recycled through the beneficiary communities 2.5 times. 340 women are being supported in six communities, with 2000 microloans distributed to date.

Envia lends exclusively to women as they are far more likely to invest in ways which benefit the family and, by extension, the community. As with the model in Bangladesh, at Envia the women also take responsibility for each other and in order to participate they have to form a group of three.

Before receiving the loan, the group of women take an eight part training course over 3 or 4 weeks within their community. This covers issues such as financial literacy, how to separate business and personal money, and how to calculate profit. Each of the three women will receive their own loan of 1500 pesos and must pay it back at either 100 pesos over 15 weeks or 150 pesos over 10 weeks. They can only proceed to the next level of loans once everyone in the group has paid back their loan. The next loan levels are 2500, 3500 and 4500 pesos and the women can decide their own repayment rate.

Women must attend weekly meetings within their communities and pay the loan back on a weekly basis. If, for any reason, they find themselves in financial difficulaties and are unable to repay their loan on a particular week, they are asked to make a minimal 20 peso contribution to show their commitment. If a woman doesn’t attend the weekly meeting, and doesn’t send her money with another member of her group, all three members of the group receive a 20 peso ($1) fine. The carrot and stick approach combining the support of group members with financial penalties clearly works well for Envia as they have a 99% repayment rate.

Another difference between the commercial microloan lenders in Mexico and Envia are the free educational programmes to help the women to grow their businesses. The women must participate in monthly business workshops which teach them about profit, promotion, PR, goal setting, branding and design. Other free classes include health, English, composting, computer skills and menopause – all of which are open to all members of the community.

Epifania Hernandez makes aprons. She is in a group with two other women. The first runs a small restaurant in San Miguel del Valle, where I enjoyed a delicious lunch. She is using her loan to buy the ingredients she needs for the restaurant in bulk, thus reducing her costs. The second runs a bakery and is likewise using the loans to purchase ingredients in larger quantities and to visit neighbouring towns to sell her rolls and empanadas. Even though I had just finished lunch, the fresh-out-the-oven bread was impossible to resist and I bought more to take back to my apartment for breakfast the next day.

In the Zapotec communities around Oaxaca, aprons are worn every day and form an integral and practical part of traditional dress. Epifania explains that there are fashions in apron design (current hot motifs include peacocks and grapes) and there is a skill in combining apron and dress colours together.

Epifania has been making aprons for 14 years and started work at the age of 14. She wasn’t that interested in school; embroidery was much more enticing. It will take her two to three days to make and embroider each of her beautiful aprons.

Epifania has been with Envia for a year and is now on her third loan which is for 3500 pesos. She uses the money to buy stocks of fabric and embroidery threads. If she has a good stock, people can choose their colour scheme when they order aprons from her, and this is increasing her clientele.

For Epifania, and the other two women I met on the tour, microfinance was working. For all three of the women, it provided a way to expand their businesses whilst reducing their costs as the loans were used to buy raw materials in larger quantities than they would otherwise have been able to afford.

Of course, the zero interest repayment on the loans is not something which many lending institutions, even those with the most benevolent of aims, can replicate. But the high repayment rate through several loan cycles, show that these rural women can be a good credit risk and would probably continue to be a good credit risk with nominal interest rates. The coupling of microloans with business education is another important factor in Envia’s success in helping the women to build sustainable businesses for the long term.

Chang criticises micro finance as he says that, in order to grow sustainably, countries need to channel individual entrepreneurial energy into collective entrepreneurship. However, community-based model of Envia is an example of collective entrepreneurship. Although loans are given individually, the women collaborate with other members of their community and they work together, supported by the educational programme, to explore ways to expand their business and take it to the next level.

Envia was only established six years ago and the long term success of this tourism-financed business model is yet to be seen. However, from an outsider’s perspective it certainly seems to be working, both for the enthusiastic overseas visitors who have the opportunity to understand how rural women live in this region and purchase direct from the producers, and for the 340 women in the Oaxaca region who are beneficiaries of Envia loans.

Administered in a sustainable manner, microfinance can undoubtedly be a powerful instrument of social change and empowerment for women in rural communities around the world. Microfinance can help to increase women’s financial, social and emotional independence, as well as improving their status within both their families and their community.

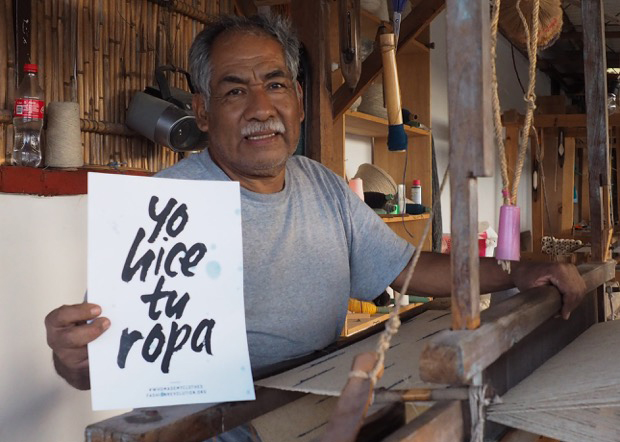

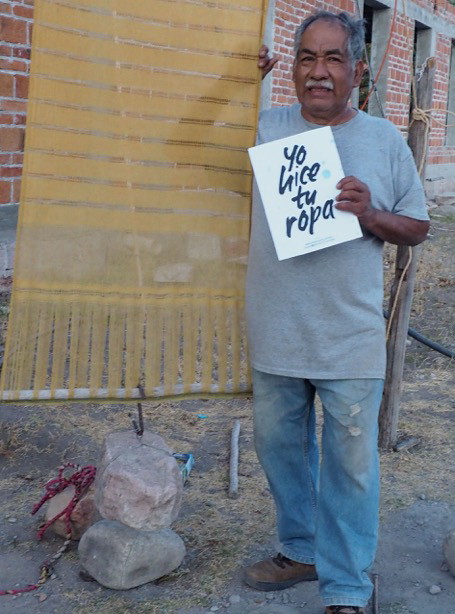

Carry Somers meets Don Arturo Hernandez at the Bia Beguug workshop in Mitla, Oaxaca, Mexico, to investigate the slow process of making a naturally-dyed, hand-woven rebozo shawl.

The earliest textiles in this region were made from the maguey cactus which, contrary to what you might expect, can produce a very delicate, fine fibre for weaving clothing, as well as a strong fibre traditionally used for bags, hammocks and fishing nets in Mesoamerica. At Bia Beguug, their rebozos are made from sheep’s wool and from cotton.

Sheep were introduced to the Oaxaca region by the Spaniards in 1521, along with the two-pedal harness loom. The Zapotec people disliked the Aztecs and so the Spanish friars found a reasonably sympathetic welcome. The Spaniards needed wool garments and horse blankets, and the sarape blankets were exported from these communities all over Mexico.

Don Arturo also uses locally-grown cotton, both the white Mexican criollo cotton which was introduced by the Spaniards, and the indigenous prehispanic coyuchi cotton. Scientists have found cotton fibres dating back 7000 years in caves near Mexico City.

If making a wool rebozo, the sheep’s wool is first spun and wound into skeins before dyeing.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GpaV7th7Rm0

Today, Don Arturo is dyeing with pericone, wild marigold. As well as producing a beautiful golden tone, wild marigold also acts as a natural mordant. Don Arturo will heat the wild marigold for a minimum of twelve hours. He has to keep checking it all day, ensuring it doesn’t boil and adding more kindling, wool and dried cactus leaves, to the fire. Three kilos of dyestuff will dye twelve 2-metre rebozos.

As well as wild marigold, he dyes with añil indigo, cochinilla cochineal, granada pomegranate and pino pine. He will also use nogal walnut, both the shell, which produces a wide range of colours from reds to browns, and also the leaves.

When dyeing other colours, such as cochineal or indigo, a mordant is needed. Don Arturo tells me:

“No hay nada mejor que el orine de niño” (There is nothing better than a boy’s urine for acting as a mordant)

His grandparents used this method and Don Arturo would like to use it, but says that customers don’t want to buy something which has been in contact with human urine, so he now uses Alumbre de potasio, potassium alum, and will also use ceniza or wood ash, left from the fire after heating the dyebath.

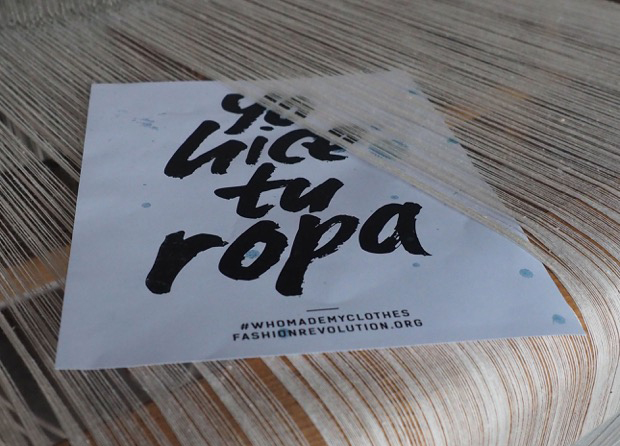

The next stage is the weaving. First the warp will be prepared. The warp is the set of longitudinal threads which are kept under tension on the loom.

Weaving is an ancient Zapotec tradition – before the Spaniards introduced the pedal loom and flying shuttle loom, the backstrap loom was widely used throughout Latin America and is still used in many communities today. Alejandro (below), Jesús, Arturo and Felipe are skilled weavers and can weave a rebozo in just two hours.

Once woven, the finished shawl is washed with a natural soap and then left to dry and release any grease for one day.

The final step is to add tassles to the end of the shawl, a job which the women often do at home while looking after their children.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vMwTf3GIBGA

Natural dyes are the antithesis of fast fashion. They produce a surprisingly wide range of colours. We have been using naturally dyed silk on our Panama hat collections at Pachacuti for the past few years and I have been astonished at both the intensity and the subtlety of the colour range.

In her 1972 book The Use of Vegetable Dyes Violetta Thurston says:

No synthetic dye has the lustre, that under-glow of rich colour, that delicious aromatic smell, that soft light and shadow that gives so much pleasure to the eye. These colours are alive.

Although natural dyes, just like analine dyes, have the potential to harm the environment, both in the collection of the dyestuffs from fragile environments and in the environmental consequences of releasing dyes and mordants into water supplies, all of the dyers I met in the Oaxaca region were very conscious of both sustainable harvesting and disposal.

They won’t provide a solution for the toxic chemical devastation caused by the garment industry in many parts of the world – we will need to look to waterless dyes and other future innovations in the dye industry to see the mainstream become more sustainable.

Hand-weaving can be a source of sustainable livelihoods around the world, particularly in rural areas, from India to Mexico. But hand-weaving doesn’t satisfy the demands of an industry requiring perfect thousands of metres of identical woven cloth, or indeed of customers unused to the odd small irregularity in the weave. We take no joy in the character of the cloth from which our clothes are made. We don’t see imperfection as a sign of the hand of the maker, but as a flaw to be eliminated from the production process.

One rebozo takes 3 days to make in total, from the preparation of the dyestuffs to the final shawl. This is fashion which draws on history and heritage. This is fashion with the odd irregularity, both in the dyeing and the weaving, and in my eyes it is all the more beautiful for it.

And maybe things are slowly changing in the fashion world. Faustine Steinmetz, who is quoted as saying that she was ‘keen to rebel against things that were flat’ showed her AW16 collection at The Tate yesterday. The textural qualities of the fabrics only served to enhance their craftsmanship.

Hunger TV said,

By returning to the very beginning, weaving the fabrics by hand rather than sourcing them from somewhere else, every element of the design process is laid bare, allowing us to have a true and raw understanding of the garment. This is wear the true ingenuity of Steinmetz’s work lies in it’s honesty.

I hope this may just be the start of a wider celebration of the honesty, tradition and skill of naturally-dyed and hand-woven fabrics. Let’s celebrate their character. It’s what makes them, and their wearer, unique.

If you are in the Oaxaca region and would like to visit the Bia Beguug workshop, I recommend signing up for Norma Schafer’s natural dye and weaving tour.

To continue to grow Fashion Revolution as a global movement for change, we need your financial support. Even the smallest donation will help us to continue delivering the resources we need to run our revolution. Please donate, be a part of this movement and help us keep going from strength to strength. We can, if you help.