80% of our fashion is made by women (mostly 18-24 years old) but we only hear about these millennial makers when they’re associated with a tragedy like Rana Plaza in Bangladesh in 2013 or the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York in 1913. Their stories are eclipsed by heartbreaking headlines that hound the fashion industry.

But there is another part of this story. It’s a story of hope. Remake has traveled to factories and dormitories throughout the world in search of the women who never make the headlines. Kashmiri who opens the yarn to make it into fabric. Maud and Rubina who stitch our blouses and jeans together. Anju who pulls out loose threads and inspects everything to ensure perfection. Each has a story and a hope for a very different future.

Meet the women behind fashion’s supply chain — we followed them from Haiti to Pakistan to China — and asked each of them to share a message to you, the end shopper. These are their stories:

Kashimiri, Yarn opener, Panipat, India

I am 25 years old and already have 4 children. I sit crouched on the floor all day, opening spindles of yarn which go on to become fabric. Panipat has a lot of needs. Open sewers, flies and trash everywhere. Only recently my children starting going to school. I now hope that they will have a better future. Go on to be somebody. I hope you can see their faces in the threads of your fabric.”

Rubina, Hoodie Sewer, Karachi, Pakistan

I am 22 years old and wanted to be a doctor. Then my father got sick, so here I am, many years later, still at a factory stitching college sweatpants and hoodies that go to America. I don’t want you to feel sorry for me. I used to be shy and scared in the factory environment. But after all the injustices I’ve seen happen here, I’ve become a labor organizer. I go to management to demand that we are not harassed, paid on time, given proper food to eat. You would not believe the things I have seen. Stitching all day long my mind wanders and I think about you often. You having fun, wearing these hoodie on campus. I wonder if you think about me ever? The woman who made that for you. I am taking English classes at night. So that one day I can at least get an office job.

Maud, Jeans Sewer, Ouanaminthe, Haiti

The factory across from the Massacre river is like paradise, with its lush green trees and paved roads. I’ve been sitting down sewing your jeans here for five years. Recently my back and neck has been hurting a lot more. But without this job, I have no way to support myself or my six siblings. After a long day, I walked across the river into my community which is pitch dark at night. There is no electricity or running water, just human need everywhere. I want to save enough to go back to university and study computer science. I want you to think about your sister Maud in Haiti, when you put on your jeans. On dark sad nights I play on Facebook with my phone and dream of the day I can be just like you.

Zheng Ming Hui, Quality Assurance, Guangzhou, China

At 19 I left my village to experience the excitement of city life. Here I am three years later, still at the same factory. I work 12 hours a day, looking at beautiful, bright patterns to make sure that there are no defects. My mother wishes I would call her more. But mostly I miss my grandmother. I only get to see my family once a year for Chinese New Year and mom makes the biggest feast. My entire life is the factory. I live in the dorms with three roommates, work all day only stopping to eat at the cafeteria. On my one day off, I am too tired to do much so I play with my phone. At night I dream of bungee jumping. I want to find someone to fall in love with and travel the world for work, taking pictures and telling stories. But for now, I am here, making sure your clothes look nice. I picture you and I am sure you look BEAUTIFUL!

Anju, Fabric Inspection, Delhi, India

I once dreamed of a life that was very different. Where I could finish my education and become a teacher. Everything changed when I was 15 and married to a man with few means. For the last 10 years, I’ve been working in a factory instead. I am proud to be an equal bread winning partner with my husband and to know that my hard work allows my children to go to school. I stand on my feet all day, pulling loose threads out of finished blouses and tops. Making sure they are perfect for you. I want you to know that I recently took a health education course on making nutritious meals with little money. I now teach what I’ve learned at my children’s school on my day off. I guess my dream of becoming a teacher has come true after all.

A 100 pair of human hands touch our clothes before they get to us. Each one of these mothers, sisters, wives and daughters are fierce and hard-working. Dreaming like us to be healthy, happy and financially secure.

Share these stories on Twitter and Facebook with your favorite brands and say: I want to know the invisible people #whomademyclothes.

Together we can #remakeourworld

“We believe art remains a step ahead and guides where fashion goes” Simone Cipriani, Head and Founder of the Ethical Fashion Initiative.

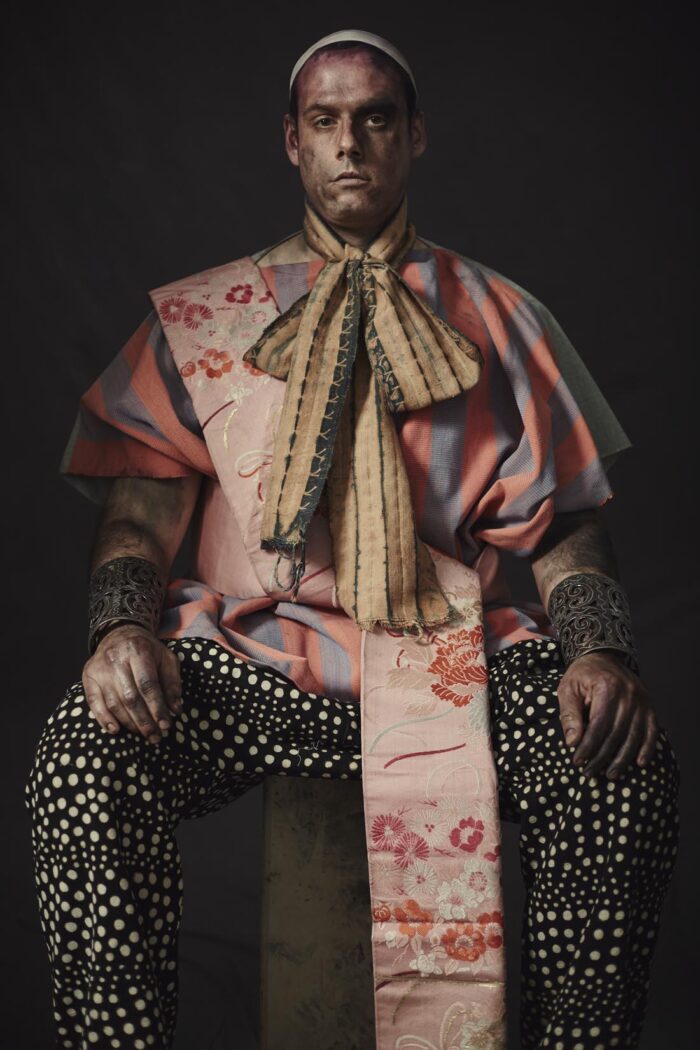

Inspired by the paintings of Pieter Bruegel and August Strindberg’s A Dream Play, a new play Elijah Green follows a divine spirit as it wanders through contemporary life. Despite unremarkable existences, the stories of the characters layer into a portrait of the interconnectivity of all humans, with each individual both the centre of the world and part of something they cannot comprehend.

The writer, director and designer Andrew Ondrejcak has connected with artisans from Burkina Faso, Mali, Kenya and Haiti to create the costume collection for his upcoming play, in collaboration with the ITC Ethical Fashion Initiative. The costumes will feature hand-painted bogolan fabric from Mali, hand-woven danfani fabric from Burkina Faso, Maasai jewellery from Kenya and fer decoupé and papier-mâché accessories from Haiti.

Andrew Ondrejcak travelled with ITC’s Ethical Fashion Initiative to Haiti, Burkina Faso and Mali to meet with artisans and source fabric, jewellery, art and items to create the costumes and the play’s set. In Burkina Faso, Andrew Ondrejcak discovered fabric handwoven by women weavers and in Mali he received a crash course in the art of bogolan by master artisan, Boubacar Doumbia.

While in Haiti, Andrew Ondrejcak was able to meet with a wide variety of artisans to source latanier hats, papier-mâché accessories and tailor made metal drum pieces and many more. ITC Ethical Fashion Initiative also sourced traditional Kenyan Maasai jewellery and samples of Kenyan crafts.

Produced by Tanya Selvaratnam and Tommy Kriegsmann/ArKtype, Elijah Green will premiere on 10 March 2016 at The Kitchen in New York. The play will be showing at 8pm from March 10-12 and 17-19. In addition, Andrew Ondrejcak will do a post-show Q&A with costume collaborators from EFI and Alba Clemente on March 17th. Find out more

About ITC Ethical Fashion Initiative

The Ethical Fashion Initiative is a flagship programme of the International Trade Centre, a joint agency of the United Nations and the World Trade Organization. The Ethical Fashion Initiative works with the rising generation of fashion talent from Africa, encouraging the forging of fulfilling creative collaborations with artisans on the continent. The Ethical Fashion Initiative also enables artisans living in urban and rural poverty to connect with the global fashion chain. Under its slogan, “NOT CHARITY, JUST WORK.” the Ethical Fashion Initiative advocates a fairer global fashion industry.

Photo credits: Georgia Neirheim

Six years after a major earthquake devastated the Haitian capital and its environs and the international community promised to “build back better,” Haitian workers say their daily lives are a struggle for survival, with their meagre wages insufficient to cover basic expenses.

In recent interviews, Haitian garment workers told the Solidarity Center that they are worse off today than before the quake. With prices rising and wages largely stagnant, their paychecks do not allow them to support themselves and their families.

“We spend almost our entire daily wage on food and transportation,” said one garment worker interviewed. “We cannot save any money and we do not have enough money to get health care or education. Our future is compromised.”

Another worker said he sometimes has to borrow money to “make sure that at least the family has something to eat.”

Haiti is the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere and one of the poorest in the world. According to the World Bank, more than 6 million of Haiti’s 10.4 million people (59 percent) live under the poverty line.

Haitian garment workers hold rare full-time jobs in an economy that is largely informal, and work for profitable multinational manufacturers, some incentivized to come to Haiti and create jobs after the quake. Yet garment-sector wages are legally set below the national minimum wage and well below what is necessary to cover basic costs. A December 2015 Solidarity Center analysis of living expenses found that the average garment worker spends 160–225 Haitian gourdes ($2.80 – $3.94) a day on food and transportation for herself, and another 395 gourdes ($6.91) on food for the household. The current minimum daily wage for garment workers, who work 48 hours a week, is 225–240 gourdes ($3.94–$4.20). The minimum wage is supposed to increase this spring, to $5.11 for an eight-hour shift.

In 2013, Haitian workers and their unions waged rallies and protests to demand that the daily minimum wage be increased to 500 gourdes ($8.75) for export apparel workers. The government set the wage at less than half of that. In 2014, the Solidarity Center found that a living wage of 1,000 gourdes per day would allow workers to meet their basic needs.

“As we mark this grim anniversary, we have to ask why the people best-positioned to revive the Haitian economy—hardworking Haitians—are handicapped by abysmal and degrading wages. Until Haitians can earn a living that allows them to do more than barely survive, there will be no real recovery,” said Shawna Bader-Blau, executive director of the Solidarity Center. “The international community and Haitian government should be ashamed of policies that guarantee poverty wages and grant concessions to multinational corporations instead of providing real opportunities for Haitians workers to improve their lives and livelihoods and build a better country for themselves and their children.”

Maud Laurent lives in Ouanaminthe, Haiti. She is 24 years old and has been sewing pant (trouser) pockets for the past five years. On her hopes and dreams of tomorrow:

“I had to drop out of school to make money but hope to go back some day and study computer science.”

Her message to shoppers:

“Picture my smile when you see ‘Made in Haiti.’ My friends and I worked hard to make those pants.”

Mackenzie O’ Donnell lives in San Francisco, California. She is 28 years old and getting a degree in business administration and environmental management. On her hopes and dreams of tomorrow:

“I plan to use my education to make a difference in the world so we can all enjoy our planet in harmony.” Her message to shoppers: “I believe my millennial generation are environmentally and socially conscious shoppers. I hope they will join our cause and help the movement grow.”

At Inspired Shopping we connect young women like Maud and Mackenzie through inspired journeys and multimedia. Our film “Made in Haiti” aims to rebuild human connections within global supply chains. We hope it moves shoppers to use their voice and shopping dollars to promote the well-being of workers like Maud.

At Inspired Shopping we connect the people who make our stuff to those who buy it. To learn more visit http://Inspiredshopping.org

#whomademyclothes?