Fashion Revolution’s theme for 2017 is Money Fashion Power which will be exploring the flows of money and structures of power across the fashion supply chain.

“There is nothing more important than performance, and fashion brands have to perform because of this greed – not a percent or two per year, but at least 10 percent quarterly, even when we’re talking about billion-dollar businesses. There is no end to the greed, so the brands are spreading themselves thin”

said trend forecaster Li Edelkoort in an interview with Deutsche Welle published this week.

Tomorrow is the fourth anniversary of the Tazreen Fashions fire in Dhaka Bangladesh. All of the garment workers were on an overtime shift to complete an urgent order when the fire alarm sounded, but managers ordered them to carry on working. As the smoke and fire spread through the building and workers eventually tried to escape, they found that iron grilles barred the windows and the collapsible gate was locked. None of the fire extinguishers appeared to have been used which suggests workers had not received fire safety training. 112 workers died and more than 200 were injured. The official who led the inquiry into the fire said

“Unpardonable negligence of the owner is responsible for the death of workers.”

After the Tazreen fire, factories were told to replace collapsible gates and lockable doors with fire-proof doors so there was always a safe exit point in the event of a fire. In the Bangladesh Accord’s initial inspection of 1600 garment factories, it was found that over 90% had lockable, collapsible gates. According to industry insiders, around 40% of all operational garment factories still have these gates, four years later.

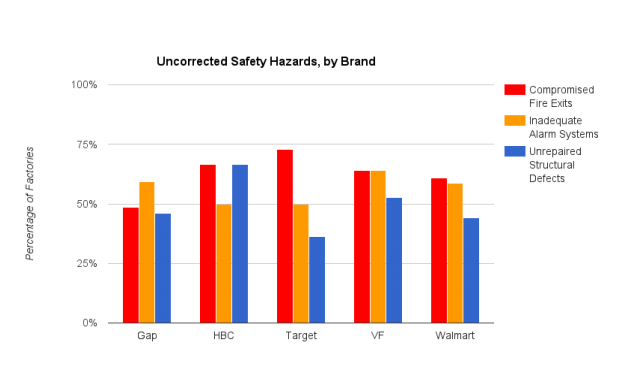

A new report published this week Dangerous Delays on Worker Safety found that of the 107 factories labelled “on track” by The Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, 99 were still falling behind in one or more safety categories. In light of Li Edelkoort’s observation that brands are spreading themselves thin, it comes as little surprise to find that brands in the Alliance, which includes brands such as Walmart, Target, Gap inc, VF Corporation (which owns Lee, Wrangler, The North Face, Vans, Timberland and others and has just published its factory lists) have yet to put in place the life-saving safety changes they pledged following the Rana Plaza disaster, which occurred five months after the Tazreen fire. 62% of factories still lack viable fire exits, 62% do not have a properly functioning fire alarm system and 47% have major, uncorrected structural problems. Deadlines for these safety measures to be implemented were supposed to be 2014/15 but have now been moved to 2018, the end of the 5 year period over which the Alliance extends.

Are brands and factory owners really so concerned with the bottom line that they cannot afford to prioritise the installation of something so basic to worker safety as a fire-proof door and the removal of locks from existing doors?

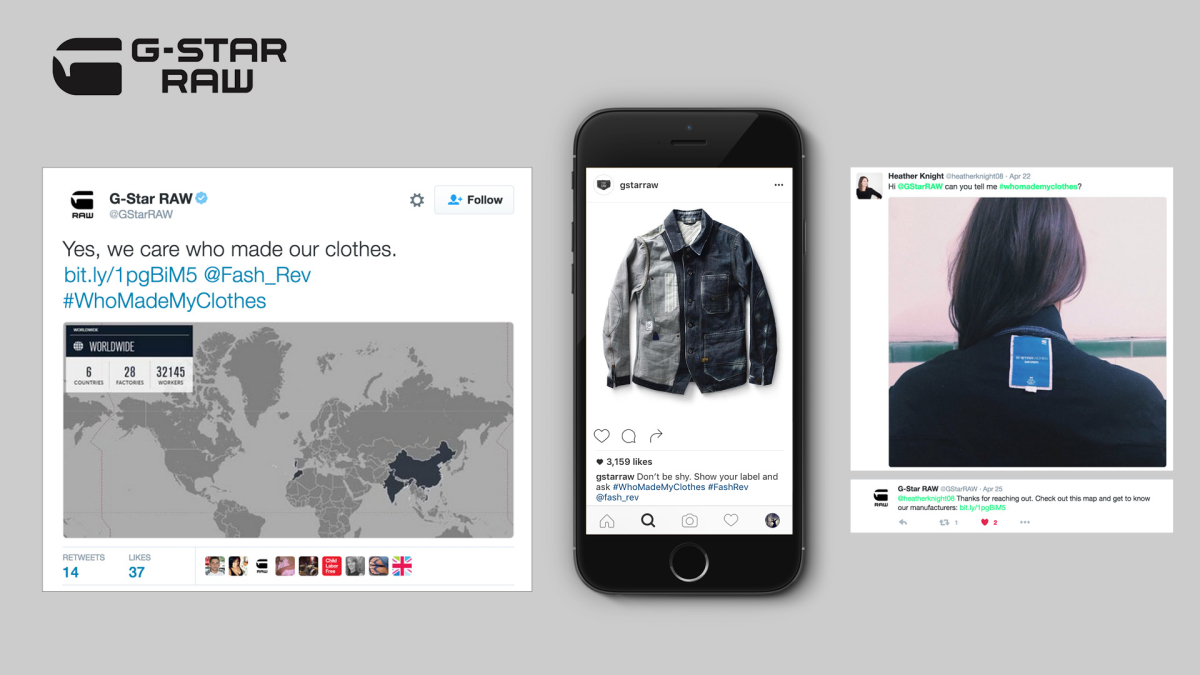

Since the Tazreen fire and Rana Plaza disaster, human rights issues are certainly more visible than ever before and there is ongoing pressure on global fashion brands to become more transparent. Companies are now being held to a higher standard and they are cognisant of this change. During Fashion Revolution Week in April, over 70,000 fashion lovers around the world asked brands #whomademyclothes on social media, with 156 million impressions of the hashtag. G Star Raw, American Apparel, Fat Face, Boden, Massimo Dutti, Zara, Jeanswest and Warehouse were among more than 1250 fashion brands and retailers that responded with photographs of their workers saying #Imadeyourclothes. Read more about our impact here.

However, the harsh reality is that basic healthy and safety measures still do not exist for millions of people who make our clothes and accessories. On 11 November 2016, 13 people died in a factory making leather jackets on the outskirts of Delhi. The front of the building had been shuttered with a metal grill which prevented the workers escaping the blaze. Deadly accidents are still commonplace in fashion supply chains and not enough has been done by brands and retailers to prevent more fashion victims; victims of neglect, oversight and the pursuit of profit.

Scott Nova, executive director of the Worker Rights Consortium says:

“What motivated Walmart and Target to do the right thing is public embarrassment. We are three and a half years on [from Rana Plaza] and they assume memories are fading.”

We have the power and, I believe a duty, to let these brands know that our memories of the Rana Plaza disaster, the Tazreen Fashions fire, and the many other tragedies which have ocurred in the name of fashion, are not fading. By asking the question #whomademyclothes we are applying pressure in the form of a perfectly reasonable question that fashion brands should be able to answer. We are asking them to publicly acknowledge the people who make our clothes; millions of people working in factories, fields, homes and other hidden places around the world. Tragedies like the Tazreen Fashions fire are preventable, but they will continue to happen until every stakeholder in the fashion supply chain is responsible and accountable for their actions and impacts.

As Li Edelkoort said, fashion brands are spreading themselves thin. As their customers, we can help make sure they start to get their priorities right and redress the imbalances of power in the fashion supply chain.

Header photo credit: A young garment worker by Claudio Montesano Casillas

Four million garment workers, mostly women, toil in 5,000 factories across Bangladesh, making the country’s $25 billion garment industry the world’s second largest, after China.

Garment workers generally are paid low wages with few or no benefits and often struggle to support their families. Many risk their lives to make a living.

On November 24, 2012, a massive fire tore through the Tazreen Fashions Ltd. factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh, killing more than 110 garment workers and gravely injuring thousands more.

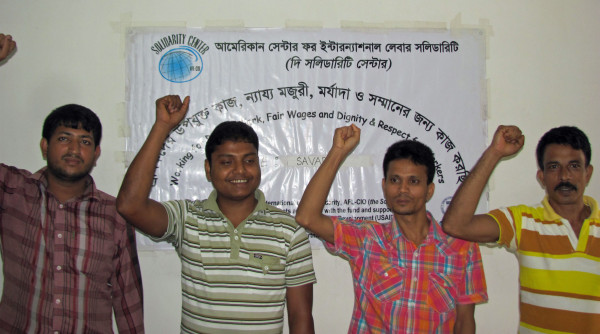

In the wake of this disaster, garment workers throughout Bangladesh are standing up for their rights to safe workplaces and living wages. With the Solidarity Center, which partners with unions and other organizations to educate workers about their rights on the job, garment workers are empowered with the tools they need to improve their workplaces together.

Learn more about the Solidarity Center’s work in the global garment industry

DISASTER STRIKES TAZREEN

On November 24, 2012, women and men working overtime on the Tazreen production lines were trapped when fire broke out in the first-floor warehouse. Workers scrambled toward the roof, jumped from upper floors or were trampled by their panic-stricken co-workers. Some could not run fast enough and were lost to the flames and smoke.

Hundreds of those injured at Tazreen, like Tahera (above), will never be able to work again. Survivors say they endure daily physical and emotional pain, and often are unable to support their families because they cannot work and have received little or no compensation.

Some 80 percent of export-oriented ready made garment (RMG) factories in Bangladesh need improvement in fire and electrical safety standards, despite a government finding most were safe, according to a recent International Labor Organization (ILO) report.

TAZREEN NOT UNIQUE

The Tazreen fire was not an isolated incident.

Months after the Tazreen disaster, more than 1,000 garment workers were killed when the Rana Plaza building collapsed. Workers were forced to return to the building despite the warnings of structural engineers that the building was unsound.

In the four years since Tazreen, fires, building collapses and other tragedies have killed or injured thousands of garment workers in Bangladesh, according to data collected by the Solidarity Center.

FACTORIES CAN BE MADE SAFE

The Tazreen fire and Rana Plaza collapse were preventable. Workers at Tazreen and Rana Plaza did not have a union or other organization to represent them and help them fight for a safe workplace.

Without a union, garment workers often are harassed or fired when they ask their employer to fix workplace safety and health conditions. They are not trained in basic fire safety measures and often their factories, like Tazreen, have locked emergency doors and stairwells packed with flammable material.

Unions have helped to improve these conditions.

They have joined together to form workplace unions and bargain for safe working conditions, better wages and respect on the job.

UNIONS SAVING LIVES

Worker voices have yielded real results.

Over the past few years, the Solidarity Center has held fire safety trainings for hundreds of garment factory workers. Workers learn fire prevention measures, find out about safety equipment their factories should make available and get hands-on experience in extinguishing fires.

When women workers form unions, they improve their working conditions. Through Solidarity Center workshops and leadership training, more women are running for union office. Women now make up more than 61 percent of union leadership in newly formed factory level-unions.

CHANGE IS POSSIBLE

Salma (below), a garment worker, and her co-workers faced stiff employer resistance when they sought to form a union. With assistance from the Solidarity Center and the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation (BGIWF), to which their factory union is affiliated, workers negotiated a wage increase, maternity benefits and safe drinking water. The factory now is clean, has adequate fire extinguishers on every floor, and a fire door has replaced a collapsible gate.

To learn more about garment workers in global supply chains and how the Solidarity Center supports them, visit www.solidaritycenter.org.

“You have forgotten the Tazreen fire incident but our actual suffering has just started,”

says Anju, who experienced severe head, eye and other bodily injuries during the fatal Tazreen Fashions Ltd. fire in Bangladesh in November 2012 that killed 112 garment workers.

Survivors of the Tazreen fire who recently talked with Solidarity Center staff in Bangladesh say they endure daily physical and emotional pain and in many cases, have little or no means of financial support because they cannot work. Some, like Anju, who is unable to work, have never received compensation for their injuries.

Bangladesh’s $25 billion garment industry fuels the country’s economy, with ready-made garments accounting for nearly four-fifths of exports. Yet many of the country’s 4 million garment workers, most of whom are women, still work in dangerous, often deadly conditions. Since the Tazreen fire, some 34 garment workers have died and 985 have been injured in 91 fire incidents, according to data collected by Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka, the capital.

Some 80 percent of export-oriented ready made garment (RMG) factories in Bangladesh need improvement in fire and electrical safety standards, despite a government finding most were safe, according to a recent International Labor Organization (ILO) report.

The Solidarity Center has had an on-the-ground presence in Bangladesh for more than a decade. Through Solidarity Center fire safety trainings for union leaders and workers, garment workers learn to identify and correct problems at their worksites. But fewer than 3 percent of the 5,000 garment factories in Bangladesh have a union. ” Despite workers’ efforts to form unions, in 2015 alone the Bangladeshi government has rejected more than 50 registration applications—many for unfair or arbitrary reasons—while only 61 have been successful. The rejections have jumped significantly from 2014, when 273 unions applied and 66 were rejected.

So that the world does not forget, here is the story of Anju and others who survived the Tazreen fire.

Anju, 45, suffers from neurological and other complications resulting from the injuries suffered during her escape from the Tazreen fire. She says the income her husband earns pulling a rickshaw cannot support their four children and pay for her medicine.

“The treatment cost is high and we cannot bear it,” she says. “Everyday life is difficult.”

Shahnaj Begum, 48, and her daughter Tahera Begum, 30, both survived the Tazreen factory fire. Shahnaj was severely injured, including the loss of her right eye. Shahnaj received some compensation, but it was not enough to pay medical bills and ongoing support.

“Many lives could have been saved if the factory was not locked. The biggest tragedy for us is the culprits have not been punished.”

Jorina Begum, 25, cannot afford medical treatment for the injuries to her spine and body she sustained at Tazreen, and her physical condition is worsening. Jorina’s sister, also injured when the factory burned, died recently. Now there is no one left to support the family. She says two things will give her peace of mind:

“I want compensation so that I can manage the support of my family members and I want to see that the person who is responsible for it is punished.”

Bilkish Begum says she and other workers at a garment factory in Bangladesh could not discuss implementing fire safety measures with their employer – even after the deadly blaze at Tazreen Fashions factory killed 112 workers three years ago. Only when they formed a union, which provides workers with protection against retaliation for seeking to improve their workplace conditions, could they take steps to help ensure their safety.

“Things have improved a lot regarding fire safety once we formed union as now we have the power to raise our voice,” she says.

Bilkish, 30, now a leader of a factory union affiliated with the Sommilito Garments Sramik Federation (SGSF), is among hundreds of garment workers who have taken part in Solidarity Center fire safety trainings this year. The Solidarity Center works with garment workers, union leaders and factory management to improve fire safety conditions in Bangladesh’s ready-made garment industry through such hands-on courses as the 10-week Fire and Building Safety Resource Person Certification Training.

“I used to be afraid about fire eruption in my factory,” Bilkish says. “But after attending trainings, I feel that if we work together, we can reduce risk of fire in our factory.”

Fire remains a significant hazard in Bangladesh factories. Since the Tazreen fire, some 34 workers have died and at least 985 workers have been injured in 91 fire incidents, according to data collected by Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka, the capital. Incidents resulting in injuries include at least eight false alarms.

In January, after a short-circuit caused a generator to explode at one garment factory, Osman, president of the factory union and Popi Akter, another union leader, quickly addressed the fire and calmed panicked workers using the skills they learned through the Solidarity Center fire training. They also worked with factory management to correct other safety issues, like blocked aisles and stairwells cramped with flammable material.

Many workers who have taken part in the trainings say they are equipped to handle fire accidents.

“We are now confident after the training that we can help factory management and other workers if there is any incident of fire in our factory,” says Mosammat Doli, 35, a leader of a union affiliated with the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers’ Federation (BGIWF). “From my experience at my factory, I have seen that an effective trade union can ensure fire safety in the factory as it can raise safety concerns,” he said.

Fewer than 3 percent of the 5,000 garment factories in Bangladesh have a union. And according to the International Labor Organization, 80 percent of Bangladeshi garment factories need to address fire and electrical safety standards. Yet, despite workers’ efforts to form organizations to represent them this year, the Bangladeshi government rejected more than 50 registration applications—many for unfair or arbitrary reasons—while only 61 were successful. This is in stark contrast to only two years ago, when 135 unions applied for registration and the government rejected 25 applications, and to 2014, when 273 unions applied and 66 were rejected.

Without a union, workers often are harassed or fired when they ask their employer to fix workplace safety and health conditions.

Because his workplace has a union, which enabled Doli to participate in fire safety training, he—like Osman and Popi Aktee—already has potentially saved lives. Together with other union leaders, he helped evacuate workers and extinguish a fire in their garment factory.

Shahabuddin, 25, an executive member of his factory union, which is affiliated with SGSF, is among Bangladesh garment workers who see firsthand how unions help ensure safe and healthy working conditions. He says his workplace had no fire safety equipment—until workers formed a union and collectively raised the issue of job safety.

“Now management conducts fire evacuation drills almost regularly. We did not imagine it just a few years back. As we formed union, many things started changing,” he says.

Mushfique Wadud is Solidarity Center communications officer in Bangladesh.

The three-year anniversary of the November 24, 2012, fire that killed 112 Bangladesh garment workers at the Tazreen Fashions Ltd., factory offers a time to reflect on garment workers’ ongoing struggle for workplaces where they will not be killed or injured and for jobs that will support their families.

The Tazreen fire was preventable, as was the collapse of the multistory Rana Plaza factory five months later in which more than 1,130 garments workers died and thousands more were severely injured.

Workers at Tazreen and Rana Plaza did not have a union or other organization to represent them and help them fight for a safe workplace. Without a union, garment workers say they are harassed and even fired when they raise safety issues with their employer. They are not trained in basic fire safety measures and often their factories, like Tazreen, have locked emergency doors and stairwells packed with flammable material.

Despite the many obstacles to forming organizations and achieving a voice at work, garment workers are at the forefront of pushing for change at their factories. With our strong and long-term grassroots connections in Bangladesh, the Solidarity Center allies with garment workers to provide ongoing training for factory-level union leaders on topics such as gender equality, workers’ legal rights and fire safety.

This photo essay gives voice to the sorrow, but also the hope, of the 4 million workers who toil in Bangladesh garment factories.

1. Bangladesh’s 4 million garment workers, mostly women, toil in 5,000 factories across the country, making the $25 billion garment industry the world’s second largest, after China. Yet many risk their lives to make a living. In the three years since the fatal Tazreen Fashions Ltd. factory fire, some 31 workers have died and at least 935 people have been injured in garment factory fire incidents in Bangladesh. Credit: Law at the Margins

2. Some 112 garment workers were killed in a blaze that swept through the Tazreen factory on November 24, 2012. Hundreds more were injured and like Tahera (above), will never be able to work again. Survivors say they endure daily physical and emotional pain, and often cannot support their families because they cannot work and have received little or no compensation. Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

3. Tens of thousands of Bangladesh garment workers held rallies on May Day this year to highlight the need for the freedom to form worker organizations to ensure safe and healthy workplaces. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

4. With few jobs available that pay a living wage, more than 600,000 Bangladeshi workers migrate each year. Yet, “after two years, after three years, they are not getting their salary,” says Sumaiya Islam, director of the Bangladesh Migrant Women’s Organization (BOMSA). “After spending $1,000 (to labor recruiters), they are not getting paid.” Credit: Shahjadi Zaman

5. Migrants from Bangladesh also risk their lives when going overseas for jobs. In June, Bangladesh families rallied to demand the government punish traffickers after many Bangladesh workers were among migrants stranded on abandoned boats by unscrupulous labor traffickers. “I did not get anything to eat for 22 days and just survived by eating tree leaves,” Abdur said, describing his journey to Malaysia. Credit: Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

6. On April 24, 2013, the multistory Rana Plaza factory collapsed, a preventable tragedy that killed more than 1,100 garment workers and injured thousands more. On the two year anniversary in April, family members and friends gathered at the site of the building to commemorate their loss. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

7. Thousands of garment workers, like Mosammat Mukti Khatun (above, looking at the Rana Plaza rubble) who survived the Rana Plaza disaster, remain too injured or ill to work and support their families. Survivors and the families of those who lost loved ones in the collapse say they are struggling to make ends meet, unable to pay rent, send their children to school or provide for other basic needs. Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

8. Days before tens of thousands of Bangladesh garment workers rallied on the two-year anniversary of the Rana Plaza collapse, the ITUC released a report that found “a severe climate of anti-union violence and impunity prevails in Bangladesh’s garment industry. The violence is frequently directed by factory management. The government of Bangladesh has made no serious effort to bring anyone involved to account for these crimes.” Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

9. The Solidarity Center launched the Bangladesh Worker Rights Defense Fund in April 2014, following an increase in violence and harassment against workers who were seeking to form unions to protect their health and rights on the job. Donations of more than $15,500 helped to provide costly medical treatment for organizers beaten or attacked while speaking to workers about their rights, and temporary food and shelter for workers fired for trying to improve their workplace. Credit: Solidarity Center/Shawna Bader-Blau

10. Despite employer and government resistance to workers’ efforts to form organizations to improve job safety, in the Dhaka export processing zone alone, 40 of the 103 factories include workers’ welfare associations, which are similar to unions. Credit: Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

11. Women garment workers primarily fuel Bangladesh’s $25 billion a year garment industry, yet women are “still viewed as basically cheap labor,” says Lily Gomes, Solidarity Center senior program officer for Bangladesh. “There is a strong need for functioning factory-level unions led by women,” says Gomes, who is leading efforts to help empower women workers to take on leadership roles at factories and in unions throughout Bangladesh. Credit: Solidarity Center/Kate Conradt

12. With strong and long-term grassroots connections in Bangladesh, the Solidarity Center provides ongoing training for garment worker union leaders on topics such as gender equality, workers’ legal rights and job safety. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

13. Garment worker union leaders sharpen their skills through regular Solidarity Center workshops, such as this one on financial management. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

14. Hundreds of garment worker union leaders have participated in this year in the Solidarity Center’s 10-week fire safety certification course. “People who worked at Tazreen and Rana Plaza had no training and had no union,” says Saiful, who took part in a recent fire training. “This training is about making sure those things never happen again.” Credit: Solidarity Center/Rakibul Hasan

For three years the victims of the worst factory fire to hit the fashion industry in recent times have been waiting for compensation. Now, finally, hope is on the horizon.

Around 120 garment workers burnt to death and hundreds more were injured when flames engulfed the multi-floor Tazreen garment factory in Bangladesh on 24 November 2012.

Trapped behind locked exists, workers jumped for their lives from the upper floors of the building, with more than a hundred sustaining permanent, life-changing injuries.

Like thousands of garment factories in Bangladesh, the workers at Tazreen fashions were making clothes for global retailers destined for Western wardrobes.

IndustriALL Global Union, together with the Clean Clothes Campaign, C&A and the C&A Foundation have set up the Tazreen Claims Administration Trust to compensate victims for losing loved ones, loss of income and to pay for much-needed medical treatment. Claims are already being processed and victims can expect to receive payments in the coming months.

Brands and retailers with revenue over US$1 billion are being asked to pay a minimum of US$100,000 into the fund for victims.

Certain brands that sourced from Tazreen, including C&A, Li & Fung (which sourced for Sean John’s Enyce brand) and German discount retailer KiK have now paid into the fund.

But more brands must face up to their responsibilities and pay.

That includes Walmart, Tazreen’s biggest customer. The anniversary falls just as the retail powerhouse stands to profit from US$50 billion of consumer spending on Black Friday this week.

Other brands that sourced from Tazreen and have not paid are U.S. brands Disney, Sears, Dickies and Delta Apparel; Edinburgh Woolen Mill (UK); Karl Rieker (Germany); Piazza Italia (Italy); and Teddy Smith (France).

Three years have passed but we cannot let brands forget the victims of Tazreen. Now it is time for a measure of justice.

by Christina Hajagos-Clausen, Textile and Garment Industry Director at IndustriALL Global Union. IndustriALL Global Union represents garment workers around the world. It is one of the key drivers of the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety signed by more than 200 global fashion retailers and covering more than two million garment workers in 1,500 factories.

Photo credit: IndustriALL Global Union