Usměvavá Kambodžanka Theavy už oblečení nevyrábí. Než se ale z řádové pracovnice organizace Sak Saum stala její národní ředitelkou, strávila dnů za šicím strojem nespočet. Nyní má Theavy za úkol koordinovat práci více než osmdesáti zaměstnanců a prodej jejich textilních výrobků. V jejím příběhu se ale zrcadlí životy mnoha dalších žen pracujících v Sak Sauk, a proto stojí za to o něm psát.

Sak Saum znamená v khmerštině důstojnost. Právě o její navrácení stejnojmenná organizace usiluje. Ženy a muži, kteří zde pracují jako švadleny nebo krejčí, mají zkušenost s obchodem s lidmi nebo jsou obchodováním ohroženi kvůli své extrémní chudobě. Theavy není výjimkou. Do organizace Sak Saum se dostala jako oběť obchodování více než deseti lety a stala se jednou z jejích prvních švadlen.

Obchod s lidmi je v Kambodži dodnes hořkou realitou zejména v chudých venkovských oblastech. Jeho obětí se stávají mladé ženy i dívky, které bývají nuceny k práci v sexuálním průmyslu, ale i muži. Ti se nechávají zlákat nabídkami práce na Blízkém Východě či ve Východní Asii, kde pak pracují za nelidských podmínek, bez dokladů a šance na návrat. Theavy byla svými rodiči prodána už jako malý dívka. Poté, co se jí podařilo utéct a žít několik měsíců normálním životem, byla znovu unesena obchodníky.

Příběh Theavy ukazuje, že obchod s lidmi není jen prázdné slovní spojení. Podle odhadů je jen v Kambodži nuceno k prostituci asi 15 tisíc žen, z nichž třetina je mladších patnácti let. O svých zkušenostech mluví Theavy nerada. Realitu nelegálního sexuálního průmyslu, kde jsou dívky drženy pod vlivem drog a pohrůžek násilí, si asi stejně nedokáže nikdo z nás představit. Když obchodníci Theavy vezli směrem k vietnamské hranici, podařilo se jí pod záminkou návštěvy toalety utéct. V drogovém opojení, s modřinami, popáleninami a rukama otlačenýma od provazů se Theavy dostala až na policejní stanici, kde se domohla pomoci.

„Strach, nulové sebevědomí a velkou touhu po tom, být v bezpečí a milována,“ tak popisuje Theavy svůj stav poté, co se jí podařilo utéct. Nucená prostituce není v Kambodži jen traumatizujícím zážitkem, ale také velkým společenským stigmatem. Ženy, které se prostitucí živily, jejich rodiny často nepřijmou zpět a v komunitě, kde žily, jen s obtížemi hledají práci a společenské uplatnění.

Pomoc a zázemí Theavy nalezla právě v organizaci Sak Saum. Ta jí poskytla ubytování, práci, vzdělání i potřebnou podporu. Zaměstnanci a zaměstnankyně Sak Saum prochází nejprve kurzem šití, poté je jim nabídnuto místo v oděvní dílně organizace. Ta sídlí v městečku Saang poblíž hlavního města Phnom Penh. Ve dvou malých budovách vznikají pod rukama zaměstnanců a zaměstnankyň organizace překrásné tašky, trička a další drobné oděvní doplňky. Součástí areálu je ale také azylový dům a vzdělávací středisko nabízející kurzy angličtiny i kurzy čtení a psaní pro dospělé.

Theavy trvalo několik let, než ze sebe setřásla nedůvěru, strach a zášť vůči lidem. Před pěti lety se Theavy vdala a záhy se jí narodil první syn. Tomu dala jméno Sokun – dar od Boha. „Chci mu dát všechno, čeho se nedostalo mně,“ říká rozhodně Theavy. Kromě naplnění svého velkého snu, se ale dočkala také pracovních úspěchů. Jako národní ředitelka organizace Sak Saum, kterou se stala, se stará o provoz organizace a snaží se předávat svou sílu těm, kteří ji aktuálně potřebují.

Markéta Nešporová

The whole story started with a need and an idea, but someone needed to make it happen.

Once you make a decision, the universe conspires to make it happen –Ralph Waldo Emerson

As we’re working on the next generation of L&E’s, I thought it was time for you to meet Atnan Z. – the master craftsman behind the 2B, Felt and Anirija collections who works at L&E London handcrafting studio in Skopje, Macedonia.

We met 2 years ago, as I was scouting for a master craftsman who will share my vision.

During our first sit-down, he told me his story – as a little boy he always played “making bags” as he waited for his father (a master craftsman) to finish work.

Naturally his first job was as a craftsman apprentice, I can’t get enough of his story about his hand shaking under the supervision of his first employer.

Hearing him talk transports me to another time, when all the master craftsman had open shops and you could see them crafting away, from pottery to handbags, (you could feast your eyes on crafts). But times have changed, now craftsmanship is a rarity around the world, so much so that he has had to make due with construction work at some point of his life.

He says working in construction has helped him think in an alternate way, which in turn, made him a better craftsman.

True to form, having worked with him for 2years now, I can say he comes up with creative ideas and thinks out of the box that enables us to push the boundaries on design.

It is in collaboration that the nature of art is revealed – Steve Lacy

Atnan and I work very closely, I come up with the ideas and he comes up with the solutions, lately he’s gotten to grips with the product so well, that he comes up with ideas and I with solutions! After which we have a testing and adjusting period before running small series.

He is a very shy and reserved man but I did manage to get him to tell us at least – what he found to be most the challenging thing about making an L&E?

“The most challenging thing was to let go of everything I knew. Working with cellulose materials requires adjusting tools and we have introduced new details in making and finishing which also required a bit of getting used to. But once you understand the purpose of every detail you understand that unlike other bags, here nothing is left to chance. “

I couldn’t have said it better! Now you know a little bit more about more about the man behind the bag.

For more info and to see Atnan’s masterpieces visit: www.lnelondon.com

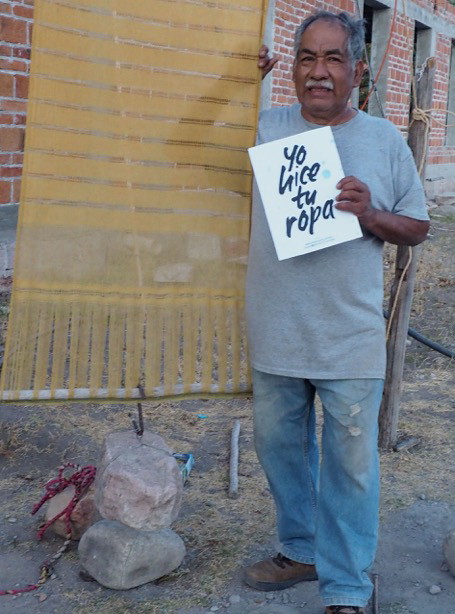

So what does community based political organisation (i.e. the kind that got Obama elected) and The Fashion Revolution have in common? Actually much more than you’d think.

The strength of Fashion Revolution Day is that it is a movement made up of hundreds and thousands of people each telling a story — of how garment workers and farmers made our clothes, of our deliberate decision to support conscious fashion and our collective efforts to spread more ethical practices.

Most often we are talking to each other — which is a good thing — but a key outcome of Fashion Revolution is, and should continue to be, getting other people to join us (a.k.a ‘growing the movement”) in transforming the fashion industry. But what is the most effective way of doing that?

I don’t come from a fashion background and so my entry into the eco-fashion world is rooted firmly in my training as an academic and as an activist. And as an activist, I bristle, alongside everyone else reading this blog, at the continued love affair our society has with cheap fast fashion. We all know the story. And the excuses.

So when we come across these pro- ‘Fast Fashion’ arguments from our friends and family and co-workers, what do we do? Turns out, the big “P” political movement (i.e. the ones that get people elected to parliaments) have a wealth of tools that can help us, as Fashion Revolutionaries, to start to break down these ‘Fast Fashion’ arguments. Chief among them is something called “the story of self”.

Let me explain.

Progressive political campaigners in their work argue that you can no longer win people over by presenting them with facts and figures. Facts and figures are still important, but they are not enough. Rather, we win people over by tapping into their core values and showing how these values can be expressed by joining in our Movement. And the most effective way of doing that, is by expressing our core values and engaging people on the story of why we are involved.

Ever been motivated into action by thinking “What if that was my child working in the factory?” or “how would I feel if my workplace was unsafe” or “what if that river was the source of my drinking water?” Then you already know what I am talking about.

Usefully, campaign theory (yes, there is such a thing!) gives us a neat little template, which we can use to tell a story about our ‘conversion’ to eco-fashion and, through this, engage people in a story that links the Fashion Revolution with the values important to them. It is about telling your story of why you are involved and it goes something like this.

- First, describe a challenge that you came across in the fashion industry that really motivated you to act. Did you look at the huge amount of waste in the fashion industry and think there has to be a better way? Or did you read the child labor statistics and think “what if that was my child”? Did you look at the water pollution from garment factories and thing I wouldn’t want to drink that?

- Second, describe your response to the challenge you saw. What choice did you make once your knew about the challenge? What different path did you see? Did you decide to cut back on your clothing purchases? Did you switch to upcycled/recycled/second hand or ethically made clothes? DId you learn how to repair your old clothes? Did you join Fashion Revolution (answer: yes!)

- Finally, provide the person you are talking with an opportunity to act — ask people to do something. Something small, this is not the time to overwhelm them with the challenge we face, but just something to get them started on making better clothing choices. For example, you could ask them to read the stories on the Fashion Revolution website.

See what you’ve done? You’ve described a situation that challenges an important universal and relatable value (desires to minimise environmental stress, prevent child welfare, or ensure clean drinking water), described how you changed (the person everyone can relate to because they are your friend, family or co-worker) and provided a template for your audience to follow suit.

You’ve provided motivation for change and a path forward to do so. And it shouldn’t take long – the whole story from start to finish should be about 2-3 minutes max.

If you want to explore more about this tool, and many others, Wellstone is a goodplace to start.

So, that’s the theory.

What does it look like in practice? Check out my story.

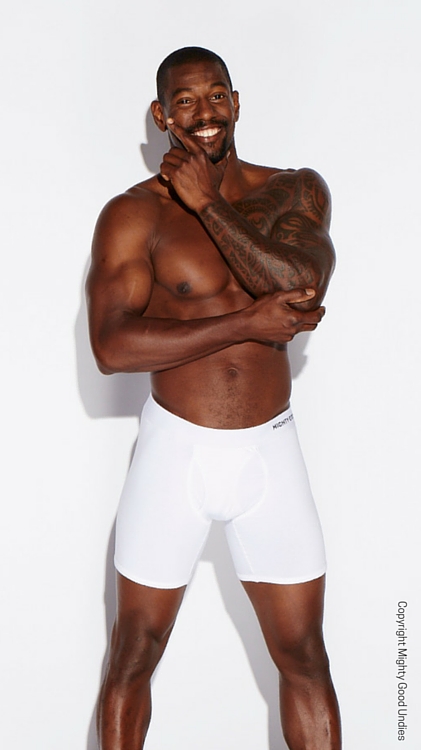

The story of my eco-fashion underwear brand Mighty Good Undies, started with my visit to India. I knew the facts and figures of the cotton industry and the potential benefits of certified organic and Fairtrade cotton, but at that stage it was all rather cerebral.

But it was only when I was sitting in the fields with the farmers from a Chetna Organics cooperative did I really get it: these people wanted to grow and sell organic cotton because organic farming meant they didn’t get sick all the time. And I realised ‘what if it was me getting sick at work?” Wouldn’t I want to change that?

And then the farmers added the kicker: many farmers wanted to join Chetna Organics but their ability to convert to organic cotton was limited by the demand for their product.

Well, I was hooked.

At that moment, I made a choice that I need to find ways to grow markets for organic and Fairtrade cotton so that more farmers, and more workers in Chetna’s production partner Rajlakshmi Cotton Mills, can get the benefits of this alternative form of trade and production*.

As the song says “From little things, big things grow…”

Happy Fashion Revolutionising

Hannah, Co-founder, Mighty Good Undies

* Okay, so starting a new ecofashion brand is probably not an option for most people, so you may want to start off with some of the brilliant suggestions in the book “How to be a Fashion Revolutionary” from the Fashion Revolution Website.

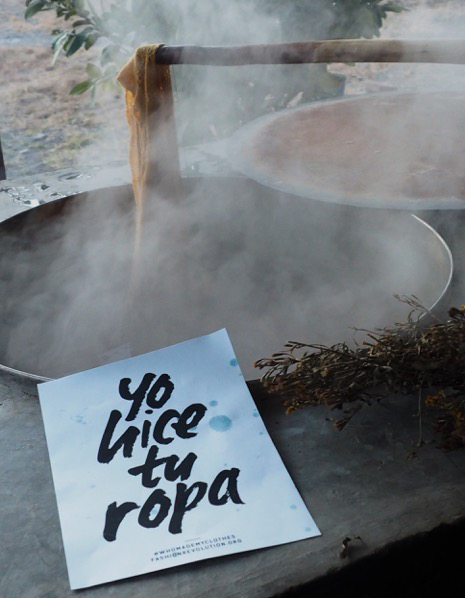

Juana learnt how to use natural dyes when she was 8 years old. She now works with her brother Porfirio in the Zapotec community of Teotitlan del Valle, dyeing wool with natural dyes and passing on her knowledge and skills to the next generation.

Before starting to dye, Juana has to prepare the wool for spinning. She cards the sheep’s wool to remove any small twigs or thorns which have got caught in the wool and then starts to twist the wool between her hands.

She will then spin the wool by hand on a spinning wheel before winding the wool into skeins in preparation for dyeing.

All of the dyestuffs she collects and uses are sustainably harvested. Dyestuffs used by Juana include musgo, an invasive species of moss which grows on trees in the region; granada or pomegranate; zapote negro, a delicious fruit local to the Oaxaca region; pericone or wild marigold (often used as a base colour with indigo or cochineal overdyed to create green or orange); marush, a local plant with no scientific name on record, añil or indigo and cochinilla or cochineal.

Juana mostly uses alumbre de potassio as a mordant and prepares the wool the day before. The mordant opens up the wool to absorb more colour and fixes it so it doesn’t fade.

The container used to dye wool is very important. You need to use enamel or stainless steel for red tones. If you use an iron pot you will get purple and in an aluminium pot you will get pink.

Cochineal is a parasitic insect which lives on the leaves of the nopal cactus, commonly known as the prickly pear. The insects produce carminic acid to deter predation by other insects.

The indigenous peope of the Oaxaca region domesticated cochineal, just as they domesticated and hybridised corn, evidence of which has been found in the caves of Yagul dating back some 8000 years. Cochineal was so important in Mexico that Montezuma I levied a tribute on all dependent states during the 15th Century, demanding the annual payment of 2000 handwoven, decorated cotton blankets and 40 bags of cochineal.

After colonisation, cochineal was Mexico’s second most valuable export after silver as it produced a deeper red than the madder which was used in Europe. The Spaniards kept the source of cochineal a secret; for over 200 years it was widely believed to be a seed.

Cochineal is widely available in the Oaxaca area, with a cochineal farm and research centre just out of town. Most dyers have nopal cactus leaves hanging in their workshops, ready for the cochineal to be harvested. Cochineal is an adaptable dye – you can add lemon to make orange or add baking soda to make purple.

[youtube v=”je_nibJlwak”]

Indigo comes in a hard paste form and is made from fermenting plants. Juana buys indigo at 1800 pesos a kilo (around $100) from Miltepec, about 4 hours away. For dyeing a deep indigo, the wool will be dyed at the beginning of the dyebath for 5 minutes, left to dry and oxidise in the sun for 3 minutes and then put back in the dyebath for a further 5 minutes. Manush leaves can be used to create a deeper blue. The dyebath gets lighter the more it is used as the oxygen takes the colour out, so a range of shades of blue can be obtained.

Teotitlan del Valle is famous for its wool weavings on the two pedal harness loom, but only about 10% of people now use natural dyes. Juana’s son Javier works with his parents. He weaves contemporary abstract rugs, interspersing straw into the wool to create the design and her nephew José Lopez is also weaving with the family.

When I met Juana, her main concern was for the survival of this ancient skill; she has taught not just her family, but the children of the community how to use natural dyes. Juana is planning to run dye workshops throughout the school holidays as a way to keep young people out of trouble and away from drugs and alcohol which are causing problems amongst the youth of the Zapotec community.

Juana says

“I am proud of my family as they are helping to continue the culture”

Concerns over artificial additives have seen a growing demand for cochineal to colour food and lipstick as some analine red dyes were found to have carcinogenic properties. Maybe we will soon realise that the skin is the body’s largest organ; the clothes we wear, the coatings used on them (formaldehyde, teflon, flame retardants) and the dyes which are used to colour them, can all affect our health.

By encouraging the next generation to see the value in natural dyes, Juana is playing her part in keeping alive the rich textile heritage of the Oaxaca region. Hopefully an increasing awareness that what we put on our bodies, not just in our bodies, affects our health will lead to increased demand for Juana’s natural dyes.

Visiting Mexico? Find out more about natural dyes with Norma Schafer’s one day natural dye study tour

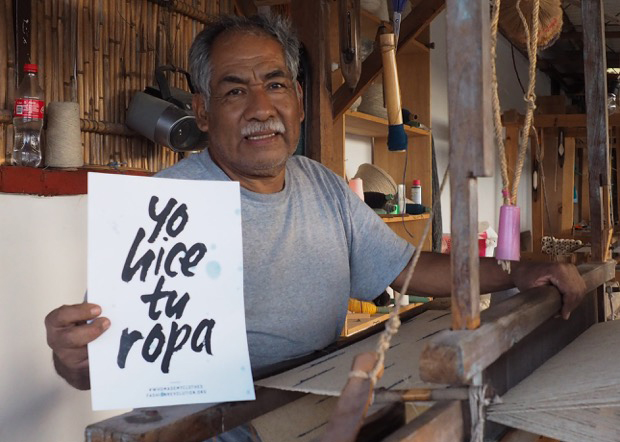

Carry Somers meets Don Arturo Hernandez at the Bia Beguug workshop in Mitla, Oaxaca, Mexico, to investigate the slow process of making a naturally-dyed, hand-woven rebozo shawl.

The earliest textiles in this region were made from the maguey cactus which, contrary to what you might expect, can produce a very delicate, fine fibre for weaving clothing, as well as a strong fibre traditionally used for bags, hammocks and fishing nets in Mesoamerica. At Bia Beguug, their rebozos are made from sheep’s wool and from cotton.

Sheep were introduced to the Oaxaca region by the Spaniards in 1521, along with the two-pedal harness loom. The Zapotec people disliked the Aztecs and so the Spanish friars found a reasonably sympathetic welcome. The Spaniards needed wool garments and horse blankets, and the sarape blankets were exported from these communities all over Mexico.

Don Arturo also uses locally-grown cotton, both the white Mexican criollo cotton which was introduced by the Spaniards, and the indigenous prehispanic coyuchi cotton. Scientists have found cotton fibres dating back 7000 years in caves near Mexico City.

If making a wool rebozo, the sheep’s wool is first spun and wound into skeins before dyeing.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GpaV7th7Rm0

Today, Don Arturo is dyeing with pericone, wild marigold. As well as producing a beautiful golden tone, wild marigold also acts as a natural mordant. Don Arturo will heat the wild marigold for a minimum of twelve hours. He has to keep checking it all day, ensuring it doesn’t boil and adding more kindling, wool and dried cactus leaves, to the fire. Three kilos of dyestuff will dye twelve 2-metre rebozos.

As well as wild marigold, he dyes with añil indigo, cochinilla cochineal, granada pomegranate and pino pine. He will also use nogal walnut, both the shell, which produces a wide range of colours from reds to browns, and also the leaves.

When dyeing other colours, such as cochineal or indigo, a mordant is needed. Don Arturo tells me:

“No hay nada mejor que el orine de niño” (There is nothing better than a boy’s urine for acting as a mordant)

His grandparents used this method and Don Arturo would like to use it, but says that customers don’t want to buy something which has been in contact with human urine, so he now uses Alumbre de potasio, potassium alum, and will also use ceniza or wood ash, left from the fire after heating the dyebath.

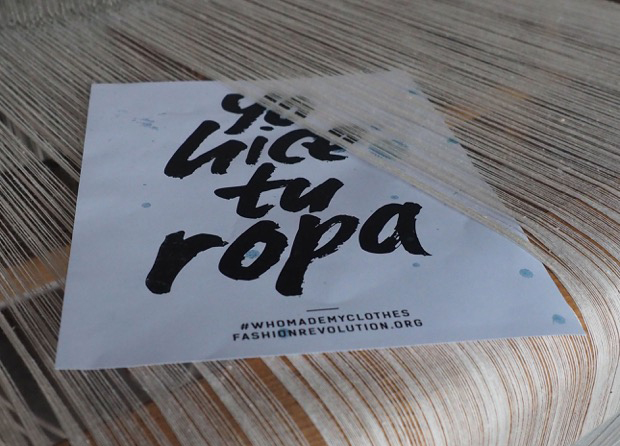

The next stage is the weaving. First the warp will be prepared. The warp is the set of longitudinal threads which are kept under tension on the loom.

Weaving is an ancient Zapotec tradition – before the Spaniards introduced the pedal loom and flying shuttle loom, the backstrap loom was widely used throughout Latin America and is still used in many communities today. Alejandro (below), Jesús, Arturo and Felipe are skilled weavers and can weave a rebozo in just two hours.

Once woven, the finished shawl is washed with a natural soap and then left to dry and release any grease for one day.

The final step is to add tassles to the end of the shawl, a job which the women often do at home while looking after their children.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vMwTf3GIBGA

Natural dyes are the antithesis of fast fashion. They produce a surprisingly wide range of colours. We have been using naturally dyed silk on our Panama hat collections at Pachacuti for the past few years and I have been astonished at both the intensity and the subtlety of the colour range.

In her 1972 book The Use of Vegetable Dyes Violetta Thurston says:

No synthetic dye has the lustre, that under-glow of rich colour, that delicious aromatic smell, that soft light and shadow that gives so much pleasure to the eye. These colours are alive.

Although natural dyes, just like analine dyes, have the potential to harm the environment, both in the collection of the dyestuffs from fragile environments and in the environmental consequences of releasing dyes and mordants into water supplies, all of the dyers I met in the Oaxaca region were very conscious of both sustainable harvesting and disposal.

They won’t provide a solution for the toxic chemical devastation caused by the garment industry in many parts of the world – we will need to look to waterless dyes and other future innovations in the dye industry to see the mainstream become more sustainable.

Hand-weaving can be a source of sustainable livelihoods around the world, particularly in rural areas, from India to Mexico. But hand-weaving doesn’t satisfy the demands of an industry requiring perfect thousands of metres of identical woven cloth, or indeed of customers unused to the odd small irregularity in the weave. We take no joy in the character of the cloth from which our clothes are made. We don’t see imperfection as a sign of the hand of the maker, but as a flaw to be eliminated from the production process.

One rebozo takes 3 days to make in total, from the preparation of the dyestuffs to the final shawl. This is fashion which draws on history and heritage. This is fashion with the odd irregularity, both in the dyeing and the weaving, and in my eyes it is all the more beautiful for it.

And maybe things are slowly changing in the fashion world. Faustine Steinmetz, who is quoted as saying that she was ‘keen to rebel against things that were flat’ showed her AW16 collection at The Tate yesterday. The textural qualities of the fabrics only served to enhance their craftsmanship.

Hunger TV said,

By returning to the very beginning, weaving the fabrics by hand rather than sourcing them from somewhere else, every element of the design process is laid bare, allowing us to have a true and raw understanding of the garment. This is wear the true ingenuity of Steinmetz’s work lies in it’s honesty.

I hope this may just be the start of a wider celebration of the honesty, tradition and skill of naturally-dyed and hand-woven fabrics. Let’s celebrate their character. It’s what makes them, and their wearer, unique.

If you are in the Oaxaca region and would like to visit the Bia Beguug workshop, I recommend signing up for Norma Schafer’s natural dye and weaving tour.

To continue to grow Fashion Revolution as a global movement for change, we need your financial support. Even the smallest donation will help us to continue delivering the resources we need to run our revolution. Please donate, be a part of this movement and help us keep going from strength to strength. We can, if you help.

Meet Margaret Kadi, creative inspirer at WORN

Recently we embarked on a journey behind the seams and met some of the local artisans working on the WORN initiative, a social venture that invests in communities worldwide to bring empowerment and education to children and young adults. Using precious recycled textile collected through various channels in Europe, the Artisans upcycle the materials into new and unique products. We catch up with Margaret Kadi, Founder of Project Sierra Leone and Pangea and Creative Inspirer at WORN to find out about herself and her work at the social enterprise.

Margaret was born in Sierra Leone but moved to London in the early nineties as the civil war began to break out across the country. She jumped on the education ladder at University in London and later worked in broadcast media for 12 years. She expresses with great sadness that she never made back until 17 years later when she visited for a two-week holiday – She was completely blown away. There was a buzz in the air and opportunities everywhere even though it is one of the poorest countries in the world. The people on the other hand are the warmest of people you would ever come across, as they are so welcoming.

Her shop soon became the go to shop for gifts and fashion accessories and things were great for about a year until the Ebola hit the country heavily affecting local businesses and entrepreneurs. The cloth weavers are based in remote villages so it became a logistical nightmare to get the goods to Freetown when most areas were under quarantine.

“My biggest passion is continuing to create a sustainable business where empowering Sierra Leoneans is at the core of what they do. The original idea was to work with predominantly women but that quickly changed, as they wanted to have an inclusive and fair business where anyone can come in and train. Poverty is rife in Sierra Leone and it affects everyone so it only makes sense to train and work with as many people as possible. My one pre-requisite though is that they have a strong work ethic.

There are many moments of happiness in life but mainly when a client tells you that you surpassed their expectations, be it with a custom piece of furniture or a tailored dress. I also love it when customers find it difficult to believe that all our products are made in Sierra Leone. They admire the quality and standard so I hope we are changing the minds of some people who think locally made means poor quality…you could not be more wrong. I feel like our customers are our ambassadors because they give us really good feedback and ideas from things they see on their travels.

I have always been creative in that I have always had my own style. Trends have never been a big hit with me and I never like wearing what everyone is wearing so I always found ways to creatively customise my clothes and accessories. When I was at University I used to shop from charity shops and blend my finds with designer wear.

Sierra Leone like a few other countries is a really challenging place to be an entrepreneur. There is just so much to worry about. Having an idea is the easiest part but then you have to worry about where to get capital from to get things going. The interest rate on bank loans is extremely high so that deters a lot of great ideas coming to light. In my case, assembling a great team that understand your vision is terribly hard so you find yourself having to micro manage everything as I am a stickler for extremely high standards.

WORN is a wonderful initiative, especially as consumers are all about slow fashion and up cycling. I honestly think it could be the start of something big – I cannot wait to see if get off the ground. What we concentrate on is the transparent supply chain. This is absolutely imperative for any sustainable business and it gives the consumer added confidence that they are making the right decision to make a purchase. Secondly, I think it expands the mindset of the artisans who are not used to working within certain perimeters.

When asked on her advice to young entrepreneurs there was one thing she stuck by – Never give up. Believe in your ideas, if you do then its a lot easier to get others to see your vision. Get a mentor if you need to, perhaps someone doing something similar so they can guide you every step of the way until you are ready to unleash your idea to the world!

The Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone affected every industry and the country as a whole as you can imagine. We are slowly getting back on our feet so things are not too bad. Our hope is to increase our collective of artisans by bringing in more, especially women that were affected by Ebola. We’ll train them in jewelry making, batik making and business skills so hopefully they can set up their own respective businesses.

There is a good crop of creative of artisans in Sierra Leone. Once you find one, they will lead you to the rest. I am so grateful for the group we have, as they are the best at what they do. The arts and culture scene is not big here so you would never get to hear about them otherwise. For us it is imperative for you to know the hands that touch and make our products. When you come into our store you will see beautiful products, two tailors working away on orders or one of our jewelry makers making a piece of jewelry. There is a greater appreciation for the products when you get to see and know the person responsible for the products you own so dearly.

We have big plans for the future. We’d like to open a training school/center where we can encourage people to come in and learn a trade – whether it is furniture making, jewelry making or tailoring. I think something like that is so desperately needed in Sierra Leone as there is a huge unemployment problem that we hope we can play our part in addressing this issue.

We have a few collaborations with some great brands so we look forward to sharing this with you in due course.

By Luke Meredith, Founder & Chief Inspirer, WORN

“You have forgotten the Tazreen fire incident but our actual suffering has just started,”

says Anju, who experienced severe head, eye and other bodily injuries during the fatal Tazreen Fashions Ltd. fire in Bangladesh in November 2012 that killed 112 garment workers.

Survivors of the Tazreen fire who recently talked with Solidarity Center staff in Bangladesh say they endure daily physical and emotional pain and in many cases, have little or no means of financial support because they cannot work. Some, like Anju, who is unable to work, have never received compensation for their injuries.

Bangladesh’s $25 billion garment industry fuels the country’s economy, with ready-made garments accounting for nearly four-fifths of exports. Yet many of the country’s 4 million garment workers, most of whom are women, still work in dangerous, often deadly conditions. Since the Tazreen fire, some 34 garment workers have died and 985 have been injured in 91 fire incidents, according to data collected by Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka, the capital.

Some 80 percent of export-oriented ready made garment (RMG) factories in Bangladesh need improvement in fire and electrical safety standards, despite a government finding most were safe, according to a recent International Labor Organization (ILO) report.

The Solidarity Center has had an on-the-ground presence in Bangladesh for more than a decade. Through Solidarity Center fire safety trainings for union leaders and workers, garment workers learn to identify and correct problems at their worksites. But fewer than 3 percent of the 5,000 garment factories in Bangladesh have a union. ” Despite workers’ efforts to form unions, in 2015 alone the Bangladeshi government has rejected more than 50 registration applications—many for unfair or arbitrary reasons—while only 61 have been successful. The rejections have jumped significantly from 2014, when 273 unions applied and 66 were rejected.

So that the world does not forget, here is the story of Anju and others who survived the Tazreen fire.

Anju, 45, suffers from neurological and other complications resulting from the injuries suffered during her escape from the Tazreen fire. She says the income her husband earns pulling a rickshaw cannot support their four children and pay for her medicine.

“The treatment cost is high and we cannot bear it,” she says. “Everyday life is difficult.”

Shahnaj Begum, 48, and her daughter Tahera Begum, 30, both survived the Tazreen factory fire. Shahnaj was severely injured, including the loss of her right eye. Shahnaj received some compensation, but it was not enough to pay medical bills and ongoing support.

“Many lives could have been saved if the factory was not locked. The biggest tragedy for us is the culprits have not been punished.”

Jorina Begum, 25, cannot afford medical treatment for the injuries to her spine and body she sustained at Tazreen, and her physical condition is worsening. Jorina’s sister, also injured when the factory burned, died recently. Now there is no one left to support the family. She says two things will give her peace of mind:

“I want compensation so that I can manage the support of my family members and I want to see that the person who is responsible for it is punished.”

Bilkish Begum says she and other workers at a garment factory in Bangladesh could not discuss implementing fire safety measures with their employer – even after the deadly blaze at Tazreen Fashions factory killed 112 workers three years ago. Only when they formed a union, which provides workers with protection against retaliation for seeking to improve their workplace conditions, could they take steps to help ensure their safety.

“Things have improved a lot regarding fire safety once we formed union as now we have the power to raise our voice,” she says.

Bilkish, 30, now a leader of a factory union affiliated with the Sommilito Garments Sramik Federation (SGSF), is among hundreds of garment workers who have taken part in Solidarity Center fire safety trainings this year. The Solidarity Center works with garment workers, union leaders and factory management to improve fire safety conditions in Bangladesh’s ready-made garment industry through such hands-on courses as the 10-week Fire and Building Safety Resource Person Certification Training.

“I used to be afraid about fire eruption in my factory,” Bilkish says. “But after attending trainings, I feel that if we work together, we can reduce risk of fire in our factory.”

Fire remains a significant hazard in Bangladesh factories. Since the Tazreen fire, some 34 workers have died and at least 985 workers have been injured in 91 fire incidents, according to data collected by Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka, the capital. Incidents resulting in injuries include at least eight false alarms.

In January, after a short-circuit caused a generator to explode at one garment factory, Osman, president of the factory union and Popi Akter, another union leader, quickly addressed the fire and calmed panicked workers using the skills they learned through the Solidarity Center fire training. They also worked with factory management to correct other safety issues, like blocked aisles and stairwells cramped with flammable material.

Many workers who have taken part in the trainings say they are equipped to handle fire accidents.

“We are now confident after the training that we can help factory management and other workers if there is any incident of fire in our factory,” says Mosammat Doli, 35, a leader of a union affiliated with the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers’ Federation (BGIWF). “From my experience at my factory, I have seen that an effective trade union can ensure fire safety in the factory as it can raise safety concerns,” he said.

Fewer than 3 percent of the 5,000 garment factories in Bangladesh have a union. And according to the International Labor Organization, 80 percent of Bangladeshi garment factories need to address fire and electrical safety standards. Yet, despite workers’ efforts to form organizations to represent them this year, the Bangladeshi government rejected more than 50 registration applications—many for unfair or arbitrary reasons—while only 61 were successful. This is in stark contrast to only two years ago, when 135 unions applied for registration and the government rejected 25 applications, and to 2014, when 273 unions applied and 66 were rejected.

Without a union, workers often are harassed or fired when they ask their employer to fix workplace safety and health conditions.

Because his workplace has a union, which enabled Doli to participate in fire safety training, he—like Osman and Popi Aktee—already has potentially saved lives. Together with other union leaders, he helped evacuate workers and extinguish a fire in their garment factory.

Shahabuddin, 25, an executive member of his factory union, which is affiliated with SGSF, is among Bangladesh garment workers who see firsthand how unions help ensure safe and healthy working conditions. He says his workplace had no fire safety equipment—until workers formed a union and collectively raised the issue of job safety.

“Now management conducts fire evacuation drills almost regularly. We did not imagine it just a few years back. As we formed union, many things started changing,” he says.

Mushfique Wadud is Solidarity Center communications officer in Bangladesh.

On 2nd December 2015, Fashion Revolution launched its first white paper, It’s Time for a Fashion Revolution, for the European Year for Development. The paper sets out the need for more transparency across the fashion industry, from seed to waste. The paper contextualises Fashion Revolution’s efforts, the organisation’s philosophy and how the public, the industry, policymakers and others around the world can work towards a safer, cleaner, more fair and beautiful future for fashion.

“Whether you are someone who buys and wears fashion (that’s pretty much everyone) or you work in the industry along the supply chain somewhere or if you’re a policymaker who can have an impact on legal requirements, you are accountable for the impact fashion has on people’s lives. Our vision is is a fashion industry that values people, the environment, creativity and profit in equal measure”

explained Sarah Ditty on behalf of Fashion Revolution.

Carry Somers, co-founder of Fashion Revolution, said

“Most of the public is still not aware that human and environmental abuses are endemic across the fashion and textiles industry and that what they’re wearing could have been made in an exploitative way. We don’t want to wear that story anymore. We want to see fashion become a force for good.”

The paper was launched at a joint event with the Fair Trade Advocacy Office in Brussels and hosted by Arne Leitz, Member of the European Parliament to mark the European Year for Development.

The event included contributions by Dr Roberto Ridolfi, Director at the European Commission Directorate-General for Development and Cooperation, Jean Lambert MEP, and Sergi Corbalán, on behalf of the Fair Trade movement.

“We need an integrated approach, from cotton farmer to consumer, and we need EU support,”

explained Sergi Corbalán.

Fashion Revolution lays out its five year agenda in the paper. By 2020, Fashion Revolution hopes that:

- The public starts getting some real answers to the question #whomademyclothes

- Thousands of brands and retailers are willing and able to tell the public about the people who make their products

- Makers, producers and workers become more visible

- The stories of thousands of actors across the supply chain are told

- More consumer demand for fashion made in a sustainable and ethical way

- Real transformative positive change begins to take root.

With many congratulations on the launch of the white paper, Dr Roberto Ridolfi proclaimed:

“My ambition, as of tomorrow, is to become a Fashion Revolutionary!”

Although our resources are free to download, we kindly ask for a £3 donation towards booklet downloads. Please donate via our donations page

[download image=”https://www.fashionrevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/FRD_resources_thumbnail_whitepaper.jpg”]Download our White Paper ‘It’s time for a Fashion Revolution‘, published December 2015.

Download[/download]

Fashion Revolution also launched a new video for the European Year for Development at the event: Why We Need a Fashion Revolution.

For three years the victims of the worst factory fire to hit the fashion industry in recent times have been waiting for compensation. Now, finally, hope is on the horizon.

Around 120 garment workers burnt to death and hundreds more were injured when flames engulfed the multi-floor Tazreen garment factory in Bangladesh on 24 November 2012.

Trapped behind locked exists, workers jumped for their lives from the upper floors of the building, with more than a hundred sustaining permanent, life-changing injuries.

Like thousands of garment factories in Bangladesh, the workers at Tazreen fashions were making clothes for global retailers destined for Western wardrobes.

IndustriALL Global Union, together with the Clean Clothes Campaign, C&A and the C&A Foundation have set up the Tazreen Claims Administration Trust to compensate victims for losing loved ones, loss of income and to pay for much-needed medical treatment. Claims are already being processed and victims can expect to receive payments in the coming months.

Brands and retailers with revenue over US$1 billion are being asked to pay a minimum of US$100,000 into the fund for victims.

Certain brands that sourced from Tazreen, including C&A, Li & Fung (which sourced for Sean John’s Enyce brand) and German discount retailer KiK have now paid into the fund.

But more brands must face up to their responsibilities and pay.

That includes Walmart, Tazreen’s biggest customer. The anniversary falls just as the retail powerhouse stands to profit from US$50 billion of consumer spending on Black Friday this week.

Other brands that sourced from Tazreen and have not paid are U.S. brands Disney, Sears, Dickies and Delta Apparel; Edinburgh Woolen Mill (UK); Karl Rieker (Germany); Piazza Italia (Italy); and Teddy Smith (France).

Three years have passed but we cannot let brands forget the victims of Tazreen. Now it is time for a measure of justice.

by Christina Hajagos-Clausen, Textile and Garment Industry Director at IndustriALL Global Union. IndustriALL Global Union represents garment workers around the world. It is one of the key drivers of the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety signed by more than 200 global fashion retailers and covering more than two million garment workers in 1,500 factories.

Photo credit: IndustriALL Global Union

‘Black Friday’ 2015 is just around the corner. Traditionally it is the day after Thanksgiving in the US when shops do an all-out sale giving the customers a chance to stock up for Christmas. Well that’s what it used to be about. Be it the US or UK, in recent years, ‘Black Friday’ has come to symbolise something more interesting, our insatiable appetite to consume. We all remember seeing the images on TV, hearing the news update on radio and saw the news headlines of the incidences which marred this day. So much so that this year leading UK superstore have announced that they will not be participating in this year’s event even though all other major super stores are[i].

One may well ask, what Black Friday has to do with ‘sustainable development’? One word………..everything! Research after research has found that our demand for goods will soon out strips the natural resources available to make them. We know that in the UK garment workers are earning as little as £3 per hour for their work (University of Leicester Feb 2015[ii]). And those in faraway lands like Bangladesh, Vietnam, Myanmar and even Ethiopia are getting paid approximately £25-30 per month[iii]. But as consumers, we close off part of our thinking mind and all queue up, physically and on-line, waiting for that deal on Black Friday.

Sustainability in the fashion industry has been addressed right through its value and supply chain. In the manufacturing sector of garments, there are all kinds of machinery that optimises water usage for washing and drying of textile and therefore has a knock on effect on the level and amount of electricity and gas used. Buildings are more ‘green’ by using solar power or alternative sources of energy and reuse and recycle rain water amongst other things. More and more manufacturers are also looking more intently on how they engage with their labour force and the provisions that are available for them. Manufacturing factories in Bangladesh are actively pursuing ‘green manufacturing’ starting with the factory space and also the environment and support for their workers[iv].

Worn Again is working with H&M and Kerring[v] to not just recycle or upcycle but create new textile based on a ‘circular resource model’ from old or ‘end of use’ clothes. New materials are also being produced from natural fibers like pineapples or banana and from seed to harvesting all aspects of the plant/ fruit is reused. M&S’s ‘SHWOP’[vi] or Patagonia’s ‘Worn Wear’[vii] are two high profile schemes which promotes and advocates ‘longer-life’ for our clothes. There are workshops on knitting in groups bit like ‘Book Clubs’. Critiques of the schemes say that these schemes are destined for the wardrobes of the rich and middle-classes. Not for the mass public. Also that dropping of our ‘worn’ clothes to the ‘poor’ of the developing nations can actually cause problems for local brands, retailers and manufacturers[viii].

In a recent BBC documentary programme, ‘Hugh’s War on Waste’, the host looks to engage with individuals who do not believe that waste is truly recycled. They are taken to a local recycling processing plant and the sceptic recyclers are still not convinced by the argument for recycling waste. It is only when they are shown actual everyday products made from recycled material that we see the recycling sceptics change their outlook.

But if it is facts we are looking for there is plenty out there in the form of research, films, images, case studies and much more. For instance the recent film ‘The True Cost’[ix] has given a very detailed breakdown of how the fashion supply chain is set up and is costing. It has been distributed in cinemas, is available online and through social media platforms. So very easily available and accessible and we still have the situation of people not following through and buying less or not queuing for ‘Black Friday’.

So far I have concentrated only on the consumption habits of developed countries. However it is the with consumers of China, India and elsewhere that brands and retailers are trying to establish a relationship with. And that is because in emerging countries material consumption lead the way as more people have disposable income and also want to have the opportunity consume or at least aspire to consume as their counter parts in developed countries[x].

So what we see now is brands, luxury brands and every day retailers positioning themselves in these new markets. It is quite normal to see nappies for babies being sold in main cities and towns of these new territories. Long gone are the days when people would use ‘terry cloth’ nappies for their babies not only because they are time consuming to maintain but also they are seen as being ‘traditional’ and not representative of the ‘modern life’ that they now live.

So attitudes are changing everywhere. It’s cyclic. In that the developed world have started thinking about ‘sustainable development’ in all walks of life. They are exploring how corporations, supply chains and individuals can make a difference. The emerging and developing countries with a growing number of people with spending power and disposable income now aspire to consume and become active participants in this global consumer market. Internet has increasingly made everything accessible within a click of a button. Social media shows you trends on a daily, hourly, minute by minute basis to satisfy ones desire.

So the notion of ‘sustainable development’ is admirable but seemingly unachievable. Unless of course as in the case of fashion you have groups like Fashion Revolution Day and their mission to connect consumer to their clothes through the ‘#who made my clothes?’ FRD asks the consumer to do the following:

- Be curious – Look at your clothes with different eyes. Ask more than “does this look great on me?”. Ask “#who made my clothes?”.

- Find out – Get to know your clothes even better.

- Do something – tweaking the way your shop, use and dispose of your clothing

Be curious is the start point of looking at our personal shopping habits. Before we go get the latest design at a cut price from the shop, the question we must ask is ‘do I really need to buy this?’, ‘Will I wear it more than once?’, ‘do I know how to take care of it?’ and what will I do when I have had enough of it?’. These questions are alongside asking the brand ‘#who made my clothes?’ Fashion Revolution has run a very successful global campaign in 2014 and 2015 with consumers, celebrities turning their clothes ‘insideout’ taking a selfie of it and asking the brand ‘#who made my clothes?’

This new curiosity will lead us to the next step ‘Find Out’. If we do not know exactly what is happening then it is difficult to change our behaviours and attitudes. There are various organisations who work on specific issues like living wage, organic cotton or on themes ‘Fair Trade’. They are a good start point for any search[xi]. There are also apps available which will assist you whilst you are shopping to find out more about the social and environmental impact of the item[xii]. New apps are coming are being developed and trialled and aims to provide more detailed information on the item of clothing origin.

‘Do something’ is personally my favourite. It can be you ask the brand, #who made my clothes? Or look at projects like http://loveyourclothes.org.uk/ set up by WRAP which gives you tips on how to manage your clothes, revamp it and much more. As mentioned earlier, high street stores like M&S or brands like Kerring have also tried to inspire their customers with alternatives to just throwing our clothes away. What is possible is sometimes difficult to choose, so a helpful list is available from Fashion Revolution’s booklet, ‘How to be a Fashion Revolutionary’[xiii]

As discussed earlier, the consumer at present is detached from what they consume be it the clothes we wear or other products. We have seen that it is only when they come face to face with evidence, is it that they start to explore further the issues on hand. So that we can move away from the future of diminishing natural resources and an un-sustainable environment we need to change attitudes through curiosity, finding out and doing something.

Author – Maher Anjum – Sustainable Sourcing and Supply Chain (Garments, Textiles and Fashion) Consultant, Operational Director Oitji-jo Collective (Part-Time), Associate Lecturer, London College of Fashion and Member, Global Advisory Committee, Fashion Revolution.

References

[i] http://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/news/northern-ireland/asda-axes-black-friday-but-rivals-tesco-sainsburys-amazon-argos-currys-pc-world-halfords-and-john-lewis-banking-on-bonanza-34188894.html

[ii] http://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/sustainable-fashion-blog/2015/feb/27/made-in-britain-uk-textile-workers-earning-3-per-hour

[iii] http://www.waronwant.org/sweatshops-bangladesh

[iv] http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/22/business/energy-environment/conservation-pays-off-for-bangladeshi-factories.html

[v] http://www.kering.com/en/press-releases/hm_kering_and_innovation_company_worn_again_join_forces_to_make_the_continual

[vi] http://www.marksandspencer.com/s/plan-a-shwopping

[vii] http://www.kering.com/en/press-releases/hm_kering_and_innovation_company_worn_again_join_forces_to_make_the_continual

[viii] http://edition.cnn.com/2013/04/12/business/second-hand-clothes-africa/

[ix] http://truecostmovie.com/about/

[x] http://www.worldwatch.org/node/810

[xi] https://www.fashionrevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Website_HTBAFR_Booklet_BCxFR_Print.pdf

[xii] https://www.fashionrevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Website_HTBAFR_Booklet_BCxFR_Print.pdf

[xiii] https://www.fashionrevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Website_HTBAFR_Booklet_BCxFR_Print.pdf

Sunday is the only day off for garment workers in Myanmar. Almost ninety per cent of garment workers in Myanmar are women. Sunday Café takes place every Sunday at Thone Pan Hla in Hlaing Thar Yar distric in Yangon. Thone Pan Hla is the first association for women garment workers in Myanmar, established in 2014 by Business Kind Myanmar.

Hlaing Thar Yar distric is the area where most of garment factories are.

Thone Pan Hla offers an opportunity for women garment workers to meet, share their experiences, get vocational training and participate in workshops. It is also a place where garment workers can relax, laugh and enjoy their free time. They can have access to magazines, books and different services, like kitchen and laundry, that otherwise wouldn’t be able to reach due to their low salaries. Swiss House is Thone Pan Hla headquarter and hosts also a hostel. Often garment workers come to work in Yangon from different areas all over the country and finding accommodation is not taken for granted.

The name Thone Pan Hla came from the name of a traditional Myanmar flower that unfortunately now is becoming rarer and rarer. It is a flower that changes colour three times a day. The name has been chosen to recall the three faces the working women have to wear: one intimate-private, one at work and one for her family.

I got the chance to participate two times at Sundays Café this summer during my internship at Business Kind Myanmar. In order to celebrate the Myanmar national holiday 19th July, Thone Pan Hla members prepared a fashion show with dresses designed by themselves and a theatrical performance narrating the story of women that have come from the countryside, arrive in Yangon in order to find a job. She finds a job in a garment factory where she is not well treated, but while discouraged she is going back to her family, she met an other woman that helps her…

The pictures were taken during the show, the preparation and the celebrations.

To learn more about Thone Pan Hla follow them on Facebook

To learn more about Business Kind Myanma

Pictures by Chiara Tommencioni Pisapia