WHY SHOULD BRANDS PUBLISH SUPPLIER LISTS?

Publicly disclosed supplier lists are helping trade unions and workers rights organisations to address and fix problems which workers are facing in the factories that supply major brands and retailers. This sort of transparency makes it easier for the relevant parties to understand what went wrong, who is responsible and how to fix it. It also helps consumers better understand #whomademyclothes.

“Knowing the names of major buyers from factories gives workers and their unions a stronger leverage, crucial for a timely solution when resolving conflicts, whether it be refusal to recognise the union, or unlawful sackings for demanding their rights. It also provides the possibility to create a link from the worker back to the customer and possibly media to bring attention to their issues.” says Jenny Holdcroft, the Assistant General Secretary of IndustriALL Global Union

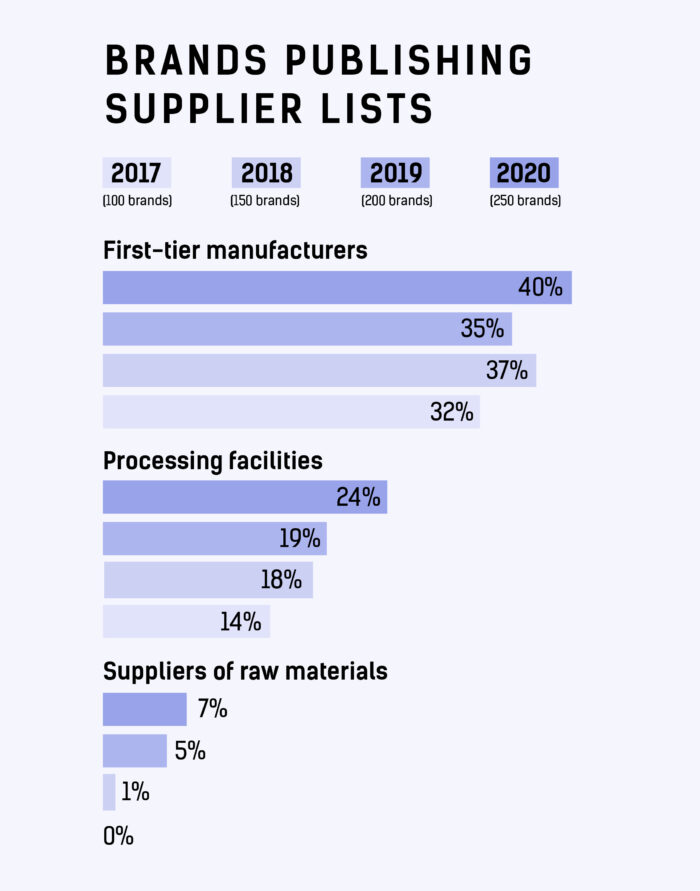

HAVE WE SEEN AN INCREASE IN BRANDS PUBLISHING SUPPLIER LISTS?

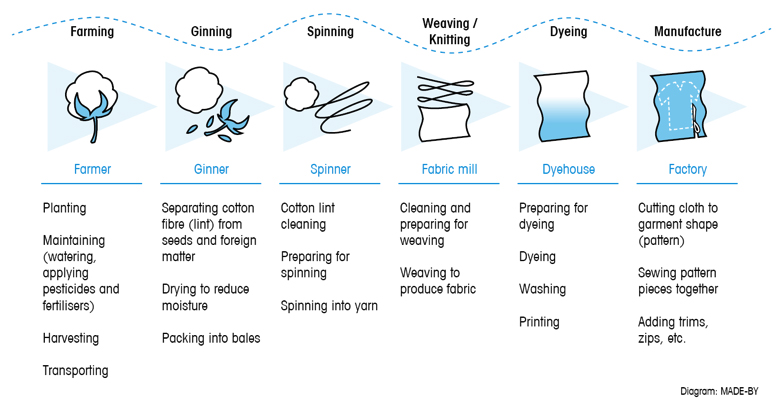

Since we began the Fashion Transparency Index in 2016, we have seen a significant increase in the number of brands publishing their first tier, processing and raw materials suppliers. In our 2020 edition of the Fashion Transparency Index, 101 out of 250 brands (40%) are publishing their first-tier manufacturers, up from 35% in 2019. These are the facilities that do the cutting, sewing and finishing of garments in the final stages of production.

60 out of 250 brands (24%) are publishing some of their processing facilities, up from 19% in 2019. These are the sorts of facilities that do ginning and spinning of yarn, knitting and weaving of fabrics, dyeing and wet processing, leather tanneries, embroidering and embellishing, fabric finishing, dyeing and printing and laundering.

And, 18 out of 250 brands (7%) are publishing some of their raw material suppliers, up from 5% in 2019. These suppliers are those that provide brands and their manufacturers further down the chain with raw materials such as cotton, wool, viscose, hides, rubber and metals.

HOW MANY BRANDS ARE NOW PUBLISHING SUPPLIER LISTS?

We have looked at large brands (over £36 million annual turnover) beyond the Fashion Transparency Index to count the number that are publishing lists of their suppliers. Below, you will find a list of over 200 brands that are publishing their first-tier manufacturers, 60 brands that are publishing their processing facilities and 21 brands that are publishing their raw material suppliers.

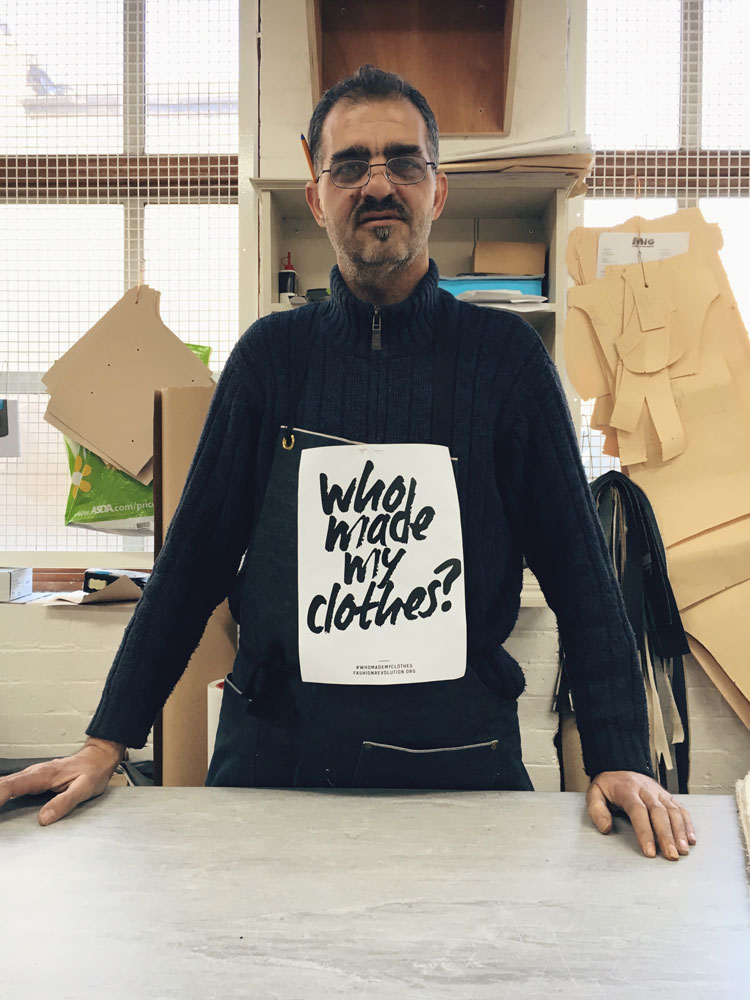

We are always pushing brands to provide more information about the people who make their clothes, and you can encourage them to do so too. Always ask the brands you buy #WhoMadeMyClothes. You can do this by tagging your favourite brands on social media and using this hashtag, or you can use our automated email tool to get in touch with them directly.

Brands who publish first-tier supplier lists

First-tier/ Tier One/ manufacturing suppliers are those which have a direct relationship with buyer e.g. production units, Cut Make Trim (CMT) facilities, garment sewing, garment finishing, full package production and packaging and storage.

& Other Stories (H&M group)

Abercrombie & Fitch

Adidas

ALDI-Nord

ALDI SOUTH

Amazon

Ann Taylor

Anthropologie (URBN)

ARROW (PVH)

ASICS

Aldi North

ASOS

Athleta (GAP Inc.)

Autograph (Speciality Fashion Group)

Banana Republic (GAP Inc.)

Berghaus (Pentland Brands)

Berlei (Hanes)

BESTSELLER

BigW (Woolsworth Group)

Black Pepper (PAS Group)

Boden

Bon Prix

Bonds (Hanes)

Boxfresh (Pentland Brands)

Brand Collective

Brooks Sports

Burton (Arcadia)

C&A

Calvin Klein (PVH)

Champion (Hanes)

Cheap Monday (H&M group)

City Chic (Speciality Fashion Group)

Clarks

Cole’s (Wesfarmers Group)

Columbia Sportswear Co.

Converse (NIKE, Inc)

Cos (H&M group)

Cotton:On

Crossroads (Speciality Fashion Group)

Curvation (Fruit of the Loom, Inc.)

David Jones

Debenhams

Designworks (PAS Group)

Disney

Dorothy Perkins (Arcadia)

Dressmann (Varner)

Eagle Creek (VF Corporation)

Eastpak (VF Corporation)

Eileen Fisher

El Corte Inglés

Ellesse (Pentland Brands)

Esprit

Evans (Arcadia)

Factorie (Cotton On Group)

Fanatics

Fjällräven

Forever New

Free People (URBN)

Fruit of the Loom

G-Star

Galeria Inno (HBC)

Galeria Kaufhof (HBC)

Gap

George at Asda (Walmart)

Gildan

H&M

Hanes

Helly Hansen

HEMA

Hermès

Holeproof Explorer (Hanes)

Hollister Co. (Abercrombie and Fitch Co.)

Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC)

HUGO BOSS

Hurley (NIKE, Inc)

Intermix (GAP Inc.)

IZOD (PVH)

JACK&JONES (BESTSELLER)

Jack Wolfskin

Jacqueline de Yong (BESTSELLER)

JAG (APG & Co)

Jansport (VF Corporation)

Jeanswest

JETS Swimwear (PAS Group)

Jockey (Hanes)

John Lewis

Joe Fresh (Loblaw Companies Limited)

Jordan (NIKE, Inc)

Junarose (BESTSELLER)

KangaROOS (Pentland Brands)

Kathmandu

Katies (Speciality Fashion Group)

Kaufland

Kayser (Hanes)

Kipling (VF Corporation)

Kmart Australia (Wesfarmers Group)

Lacoste

Lee (VF Corporation)

Levi Strauss & Co.

Lidl

Lindex

Littlewoods (Shop Direct)

Loblaw

Loft (Ascena)

Lord & Taylor (HBC)

lucy (VF Corporation)

Lululemon

Majestic (VF Corporation)

Mamalicious (BESTSELLER)

Mammut

Marco Polo (PAS Group)

Marimekko

Marks & Spencer

Matalan

MEC

Millers (Speciality Fashion Group)

Missguided

Miss Selfridge (Arcadia)

Mizuno

Monki (H&M group)

Monsoon

Morrisons (Nutmeg)

Name It (BESTSELLER)

Napapijiri (VF Corporation)

Nautica (VF Corporation)

New Balance

New Look

Next

Nike

Noisy May (BESTSELLER)

Nudie Jeans

Old Navy (GAP Inc.)

Only (BESTSELLER)

Only & Sons (BESTSELLER)

Outerknown (Kering Group)

Outfit (Arcadia)

OVS

Patagonia

Pieces (BESTSELLER)

Pimkie

Playtex (Hanes)

Primark

Prisma (S Group)

Puma

R.M Williams

Razzamatazz (Hanes)

Red or Dead (Pentland Brands)

Reebok (Adidas Group)

Reef (VF Corporation)

REI Co-op

Review (PAS Group)

Rider’s by Lee (VF Corporation)

Rio (Hanes)

River Island

Rivers (Speciality Fashion Group)

Rock & Republic (VF Corporation)

rubi (Cotton On Group)

Russell Athletic (Fruit of the Loom, Inc.)

Sainsbury’s – Tu Clothing

Saba (APG & Co.)

Sak’s Fifth Avenue (HBC)

Selected (BESTSELLER)

Sheer Relief (Hanes)

Sisley (Benetton Group)

Smartwool (VF Corporation)

SPALDING (Fruit of the Loom, Inc.)

Speedo (Pentland Brands)

Sportscraft (APG & Co.)

Supré (Cotton On Group)

Target

Target Australia (Wesfarmers Group)

Tchibo

Ted Baker

Tesco

The North Face (VF Corporation)

The Warehouse

Timberland (VF Corporation)

Tod’s

Tommy Hilfiger (PVH)

Tom Tailor

Topman (Arcadia)

Topshop (Arcadia)

Under Armour

Uniqlo (Fast Retailing)

United Colours of Benetton (Benetton Group)

Urban Outfitters (URBN)

Van Heusen (PVH)

Vanity Fair Lingerie (Fruit of the Loom, Inc.)

Vans (VF Corporation)

Vassarette (Hanes)

Vero Moda (BESTSELLER)

Very (Shop Direct)

Victoria’s Secret (L Brands)

Vila Clothes (BESTSELLER)

Voodoo (Hanes)

Wallis (Arcadia)

Warner’s (PVH)

Weekday (H&M group)

White Runway (PAS Group)

Wrangler (VF Corporation)

Yarra Trail (PAS Group)

Y.A.S. (BESTSELLER)

Zalando

Zeeman

Total: 204

Brands who publish processing facilities list

Processing facilities (often referred to as facilities beyond tier 1) are involved in the production of clothing whose activities could involve ginning and spinning, knitting, weaving, dyeing and wet processing, tanneries, embroidering, printing, fabric finishing, dye-houses and laundries.

Adidas

Anthropologie (URBN)

ASICS

ASOS

Banana Republic (GAP Inc.)

Bon Prix

Burton (Arcadia)

C&A

Calvin Klein (PVH)

Champion (Hanes)

Clarks

Converse (NIKE, Inc)

Debenhams

Disney

Dressmann (Varner)

Eileen Fisher

Ermenegildo Zegna

Esprit

Free People (URBN)

Gap

Gildan

G-Star RAW

H&M

Hanes

Helly Hansen

HEMA

Hermès

Jack Wolfskin

Jordan (NIKE, Inc)

Kaufland

Levi Strauss & Co.

Lindex

Lululemon

Monsoon

New Balance

New Look

Nike (Nike, Inc.)

Nudie Jeans

Old Navy (GAP Inc.)

Patagonia

Puma

Reebok (Adidas Group)

Russell Athletic (Fruit of the Loom, Inc.)

Sainsbury’s – Tu Clothing

Target

Tchibo

Tesco

The North Face (VF Corporation)

The Warehouse

Timberland (VF Corporation)

Tommy Hilfiger (PVH)

Topman (Arcadia)

Topshop (Arcadia)

Uniqlo (Fast Retailing)

United Colours of Benetton (Benetton Group)

Urban Outfitters (URBN)

Van Heusen (PVH)

Vans (VF Corporation)

Warner’s (PVH)

Wrangler (VF Corporation)

Total: 60

Brands who publish raw materials supplier list

Raw material suppliers are those which provide the commodity for the production of clothing e.g. cotton, wool, viscose or polyester.

ASOS

Balenciaga (Kering)

Bottega Veneta (Kering)

C&A

Eileen Fisher

Ermenegildo Zegna

Esprit

Gucci (Kering)

H&M Group

Lululemon

Marks & Spencer

Morrisons (Nutmeg)

Nudie Jeans

Patagonia

SAINT LAURENT (Kering)

Tesco

The North Face (VF Corporation)

Timberland (VF Corporation)

United Colours of Benetton (Benetton Group)

Vans (VF Corporation)

Wrangler (VF Corporation)

Total: 21

Please note: We are not endorsing the brands included in this list; this is not a ‘seal of approval.’ While publishing supplier lists is a necessary step towards greater transparency and improved conditions in fashion supply chains, it does not guarantee ethical business practices. However, we hope you find this list informative and continue to ask brands #whomademyclothes.

This list is not exhaustive and only accurate as of April 2020; if you are aware of other large brands (over £36 million annual turnover) that are publishing their suppliers, please let our Policy and Research team know at transparency@

By Allison Griffin for Remake

Few things are more powerful than a room full of women who have something to say.

As part of our Remake Journey we traveled 2 hours outside of Phnom Penh along dirt roads to a small school in the middle of rice fields, one of the few safe places makers are able to unite to talk about their rights without the police breaking up the meeting.

This gathering was hosted by Solidarity Center, to help makers fight for their rights. We learned that when big factories agree to cheap prices and tight deadlines, they often can’t meet these demands. So they ship orders off to fly by night operations–dark, dingy subcontracted factories where the conditions are the worst.

The women we met had sneaked out labels from the brands they illegally sew for including Zara, H&M and Tommy Hilfiger. It was dangerous for them to sneak these photos and labels out but they did it anyway, in the hope that we and you as readers would help them, to ask these brands pressing questions about why they worked such long hours for so little.

I had the honor of sitting down with one such maker, Char Wong. This is her story:

I grew up in a family of eight children raised by a single mother. I was a farmer before working in a subcontracted garment factory. I found work in a subcontracting factory to earn more money and provide a better life for my own family, but the pressure from the daily quotas is stressful and the money is not enough.

I support my 16-year-old son, 10-year-old daughter, my elderly mother, along with my husband who is a farmer. I struggle to feed everyone with the minimum wage and extra $2.50 a day that I earn. My mother has diabetes and her medicine costs $30 a month, over 20 percent of my monthly income. I also want to save money for my children’s education.

wanted a better life for myself and my family which is why I took this work. But life has become harder. I get paid per 12 pieces, but if there’s even one single error in the batch, I don’t get paid at all.

A few years ago, the factory would receive an order for a new design every two or three months, but with the new fast fashion cycles, it now gets more and more new designs in a shorter amount of time. Learning complex designs is very difficult and we get no training. Sometimes it takes two or three hours just to learn and the factory supervisor scolds us for any mistakes. The more time it takes to learn a design, the less time I have to meet the quota and the less money I make. I typically make $5 a day, but with the more complex designs, I only make $2 a day.

Sometimes I cry because I fear I won’t meet the quota and get paid.

Like most parents from all corners of the world, I want a better future for my two children. I hope to pay for their college education so that they can work in Cambodia’s government. Government jobs pay well and do not require hard physical labor. I hope that my children can be government leaders and help improve the conditions and rights of future garment factory makers, just like myself.

I am grateful for organizations like the Solidarity Center, who teach us about our rights. I am learning to speak up more. I want my story and my colleagues’ stories to spread to people throughout the world.

You being here, listening, makes me hopeful.

I definitely felt a lot of girl power throughout the day, both from our own all female crew and the makers we met. These women are not playing victims, but fighting for their rights and educating themselves on their rights. Speaking with Char Wong, I realized that the hopes she has are fundamentally no different from mine–for a fulfilling life. I hope as a designer, I can be a part of the change and that this story moves you to buy better. Together we can #remakeourworld.

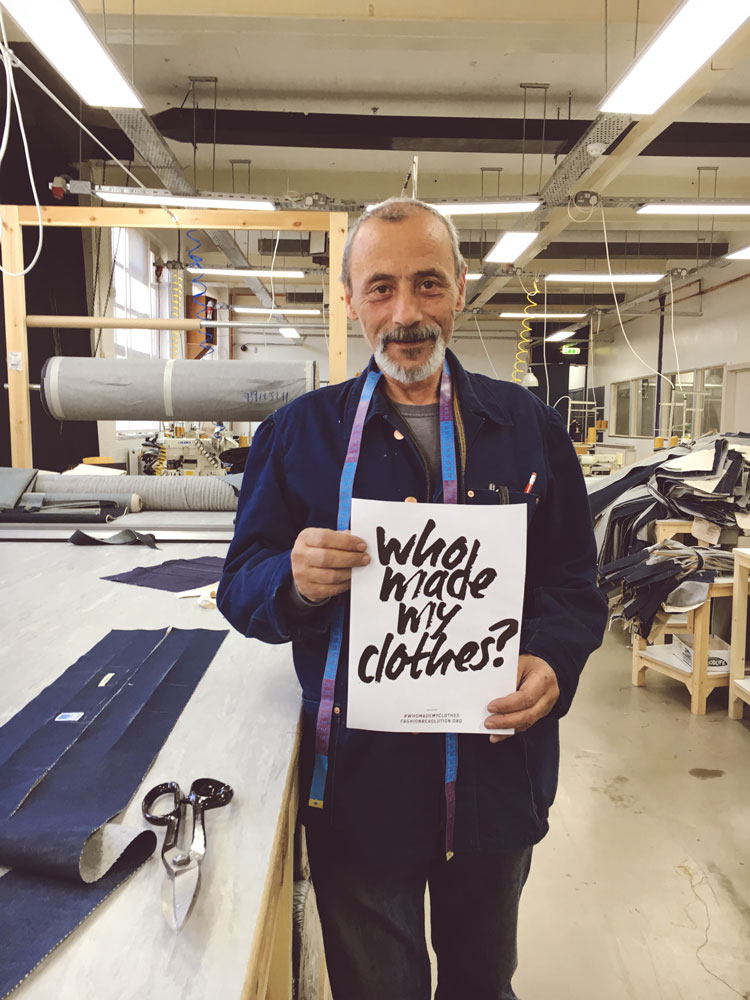

We are the first factory brand to be making authentic premium quality jeans in London for at least the last fifty years. Perhaps the first ever to be making selvedge denim garments in London.

As a community focused enterprise, all factory employees and machinists are shareholders in the company. A place to observe and learn how jeans are created and to visit our allotment growing Japanese indigo to dye the garments.

Name : Mr Husseyin

How long have you been in manufacturing? 40 years

How did you get into manufacturing ? Both my father and grandfather were tailors in Turkey for their whole lives and it influence me to do the same.

How does working here compare to other jobs in manufacturing? It is better than anywhere I have worked before.

What does working here mean to you? I have more opportunities and better life prospects.

Name : Ms Emine

How long have you been in manufacturing? 10 years

How did you get into manufacturing ? I learned to sew In Bulgaria and have been sewing for 10 years now. I’ve lived in London for 4 or 5 years and I am very happy to use the skills I have here.

How does working here compare to other jobs in manufacturing? It is better than any other factory I have worked in. The space is much cleaner and bigger and a much nicer place to work.

What does working here mean to you? It means I can carry on using my skills to earn a good living to make a better life for myself.

Name : Mr Kenan Habali

How long have you been in manufacturing? 40 years +

How did you get into manufacturing? It is the only thing I know and the thing I know best.

How does working here compare to other jobs in manufacturing? It is better than anywhere I have worked before.

What does working here mean to you? Bread Money

Name : Mr Iliev

How long have you been in manufacturing? 22 years

How did you get into manufacturing? I enjoy the job, I used to work in manufacturing in Bulgaria where I am from.

How does working here compare to other jobs in manufacturing? The conditions are much better and we are treated equally.

What does working here mean to you? It means I can come to work everyday and work hard to earn a good living

Name : Mr Dimitar Conev

How long have you been in manufacturing? 27 years

How did you get into manufacturing? I like the job, sewing and manufacturing is something I enjoy doing.

How does working here compare to other jobs in manufacturing? We are paid a lot better and the working space and conditions are a lot better.

What does working here mean to you? It means I can earn a living and afford a better standard of life.

Name : Ali

How long have you been in manufacturing? 30 years

How did you get into manufacturing ? It is my favourite job. I enjoy sewing and manufacturing more than any other job.

How does working here compare to other jobs in manufacturing ? This is the nicest factory I have worked in.

What does working here mean to you? It means I can earn a proper living.

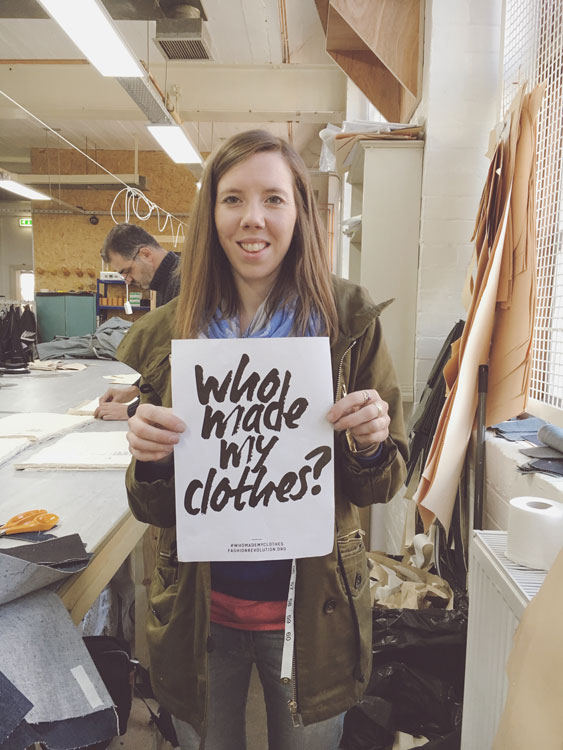

Name : Megan Fisher

How long have you been in manufacturing for ? I have been sewing for 15 years, since I was a little girl.

How did you get into manufacturing ? My mum was always really good at sewing which really inspired me, and I enjoyed textiles classes as school, the passion just grew from there.

How does working here compare to other jobs in manufacturing ? It’s really different because everyone is really honest and open. its a very transparent company, which means we have lots of visitors to see what we do.

What does working here mean to you ? It mean that i get to live an exciting life of living and working in London.

The antithesis of fast fashion, denim jeans are known universally as the quintessential egalitarian garment, with a slow heritage dating back 150 years. Launching in April 2016, the Blackhorse Lane Ateliers is an entirely unique factory brand and manufacturer of superior quality denim goods. Based within a tastefully renovated 1920s factory building in Walthamstow, the brand combines the production of artisan jeans with the establishment of a modern methodology for community living – Think Global, Act Local.

The key element of the Blackhorse Lane Ateliers manifesto has been to challenge the commonly held, modern day attitude of short-term gains, instant gratification and disposability, by implementing a more sustainable, ethical and transparent business model, to the advantage of the consumer. In order to keep the carbon footprint low, each pair of jeans will be produced within their London Atelier and crafted by local Londoners, using only the finest quality selvedge and organic denim, expertly sourced from Europe and Japan.

The fashion industry is incredibly complex.

Fashion is a global network. From growing the cotton, weaving it into fabric, dyeing and finally sewing the garment together, each step is completed by a different group of people, in different regions and even countries. Some brands have over 500,000 different products on the market at once worldwide, thousands of factories associated with them, and millions of workers all having a hand in creating their products.

It is positive that the fashion industry is able to support the employment of so many people, in regions where opportunities can be limited. The challenge, however, is making sure that the livelihoods of these workers are protected, sometimes even above the accepted standards in that country, and that the environments in which materials are extracted and processed are not negatively impacted by these activities. Many brands have invested significant resources to evaluate and decrease these impacts, however numerous continue to struggle with achieving transparency of their supply chain in the first instance.

Why is supply chain transparency a challenge?

The strength of fashion brands is in providing consumers with finished products they want to purchase – it is not in growing cotton, mining tin, dyeing wool, or all other stages of production of fashion. Because of this, their supply chains are setup to primarily place orders directly with factories which produce their final products. Some brands do purchase key fabric or components to their products, however brands are towards the end of incredibly intricate networks of factories and workers. To achieve transparency, brands need to work backwards to identify these factories who have had a hand in producing the components used to create their products.

We lead projects with brands to uncover their supply chains. These projects are always an ongoing process of communicating the intent to suppliers. The focus is on building trust in that brands are not seeking to leapfrog over suppliers to secure better commercial deals with upstream suppliers, but rather, honest attempts at uncovering who made their clothes and how these were made. We have had some great successes in these projects, finding ways to decrease impacts quickly, connect brands to workers who they would’ve never been able to tell stories about otherwise (e.g., Mongolian goat herders), and build comprehensive pictures of their supply chains and their associated risks. In some cases, we find deceptive behaviour or suppliers being unwilling to share this information. The brands we work with then need to make a decision. Some have decided to make a stand that it is no longer acceptable to them to source from suppliers who do not share this information. Others are still trying to get this supply chain shift sold internally. However, in both cases, the important thing is that transparency is now a factor in sourcing, and is being discussed by both sustainability teams and commercial teams as the new basis for further impact reductions. Without having visibility to these suppliers, brands are unable to support impact reductions more upstream in the supply chain. Once visibility is established, we have seen impact reductions of all sizes, from investing in new machinery to simply adding nozzles to hoses to save resources.

A fundamental shift is coming

By 2050, the global population is expected to reach nine billion people – all of which will not only need clothes. Climate change has already began impacting harvests for materials like cotton worldwide, and is only expected to cause further supply disruptions in the coming years. Industrial pollution too has devastated environments, with 43% of rivers in China being unsuitable for human contact (not consumption – contact). Competition for resource is ever increasing with poor yields from harvests, and even with resources we take for granted such as the groundwater level in Bangladesh dropping by multiple metres every year, requiring factories and communities to continue drilling deeper and deeper to find water.

Legislation and international guidelines are also changing worldwide which means that companies will have full responsibility for the social and environmental impacts of their supply chain from start to finish. For some brands, this will be a catalyst for action. For others who have already invested in projects to identify and support suppliers, their first mover advantage has put them in a better position to comply with these legislations, but also have created some other potential benefits. A key high-street brand recently shared that their commitment to sourcing Better Cotton Initiative cotton for their products created a space to build trust with suppliers, get to know them better, and support them with their challenges.

Transparency as an opportunity

We must be aware that opening up an entire global industry cannot happen overnight. Instead we should celebrate some of the leaders who continually engage with their supply chains, and share with the world some of their findings (both positive and negative) and some of their stories.

Transparency will be the vehicle by which brands can identify their supply chain, engage with these suppliers and improve the environmental and social impacts associated with the production of their products. Sustainability engagement has moved far beyond a charitable exercise, it is becoming a critical business activity.

Transparency is set to be a game changer on supply chains and effective action can begin to make this a reality.

Stefanie Maurice, Principal Consultant, MADE-BY

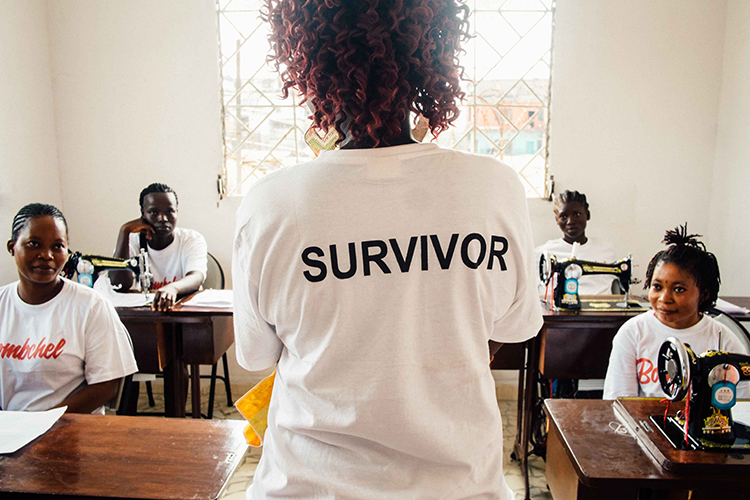

Meet Beatrice. At 27, Beatrice is a mother to a 14-year-old daughter, an Ebola widow, and she is learning to write the alphabet in her spare time. Now that she works at The Bombchel Factory, she is able to support herself and her family for the first time in her life.

Before she became a Bombchel, Beatrice sold fish in the market sometimes, but in her own words at our first meeting, ‘whole day I not doing nothing at home.’

The Bombchel Factory is an ethical African fashion wonderland based in the heart of Monrovia, Liberia that trains disadvantaged women like Beatrice how to sew contemporary garments for sale.

When I started The Bombchel Factory, I just needed a place where women would make clothes for sale in my store, Mango Rags, or for the occasional US festival. I knew I wanted to help women as much as I could, being that I am a proud woman and most of the tailors in Liberia are men. In a country where most of the women are uneducated and unskilled workers, I couldn’t have imagined that we would get to teach women how to one day write their name, like Beatrice. I didn’t expect we would find a team mama, Sis Emma, who keeps the women in line but also builds their confidence. I didn’t think we would have a future Baby Bombchel on the way from our expecting manager, T Girl. I definitely didn’t expect that we could raise $60,000 on a crowdfunding campaign all the way in little Liberia!

Through The Bombchel Factory, I learned that fashion can do more than just transform the way a woman looks, but it can revolutionize the way she lives. The most exciting things I’ve learned from our wonderland have to do with the people who have helped to build it.

In a country that has seen civil unrest, Ebola, and everything in between, we’re excited to be ethically stitching together a silver lining for Liberia.

by Archel Bernard

22-year-old Huang has been working in garment factories for about five years. Photo by Daniel Huang

I have been working in garment factories for four or five years. I am 22 years old now. When I graduated from junior high school I had nothing to do. Someone told me how good making clothes was and they introduced me to the industry. At that time I thought I was young so it would be good to learn something new. I started to make clothes then and I still do now.

I had many dreams when I was little, such as being a doctor or a policewoman or even being rich. I was so naïve then. Take the doctor dream for example. I am so scared of seeing blood. I once saw someone’s injury from a car accident. OMG, it was terrible. I couldn’t even look at the wound, let alone touch it. I even saw a dead body once. How can I be a doctor if I am so afraid of blood, injuries and death?

My plan is to work at the garment factory for a few more years but I won’t do it for the rest of my life. I will go back to my hometown to open a store in a few years. I just want to open a store, but I don’t know what kind yet.

When I graduated from junior high school, my mom asked me to keep studying but I didn’t. I was in a dilemma. My mom didn’t want me to work in the city at such a young age. She wanted me to stay in school but I was rebellious. I didn’t do well in school so I thought, “Why bother studying and spending money on my education?” I just came to the city to work so I could support myself. It was a very difficult decision for me. My mom tried to force me to study but I wouldn’t go. Honestly, I regret the decision a bit. I should have gone back to school.

For girls, it is better to learn something not so tough. I think I would learn to make patterns for clothes or something using electronic devices if I could go back to school. I want to learn something easy because I am a lazy person. I like doing finishing work for others so I don’t have to make everything from the beginning.

In terms of social life, garment factory workers like us don’t have time to take a break because we need to do overtime to keep up with production. I go out on public holidays, but there are so many people and cars during that time. I remember I went to a museum park once and I waited in line to get in from 7am to 10 am at the entrance. There were so many people there. For me, having a social life means going out shopping. Girls like shopping and buying cosmetic products. We should spoil ourselves from time to time.

For example, I once spent 2000 RMB (330 USD) to buy a set of Mary Kay products. It is a big brand that I can trust. I buy skin care products instead of make-up. It is important for me to take good care of my skin to look young and pretty because there is dirt and dust around the factory. When I first came to the city, my skin was dark but my skin is getting better with good care. I think it is better to take care of my skin as I grow older. Dirt around the factory may clog the pores in my skin and cause various skin problems. To help, I give myself facials.

Concerning other self-care, I rarely exercise. Firstly, I don’t have much time and secondly, I am too lazy. I will sleep late whenever I have a day off. I am so lazy that I miss the time to exercise. I also hate to wash my clothes because I am lazy. I think it’s best if there is a washing machine but there is no machine so I just wash the clothes myself. When I finish my shower at night, how I wish someone would wash my clothes and I could just lie in bed and play with my phone. But no one is there to help me. Even if I forget about them for half a month, I still have to wash them myself.

This interview has been edited. It was conducted on July 13, 2014 at the factory where Huang works in the industrial area of Yantian east of Shenzhen, China. You can read the original interview here

Primary Voice is a collection of primary source interviews dedicated to documenting the living stories of garment factory workers worldwide. It was created by urbanist Mikaela Kvan. To read more interviews and to get in touch visit www.primaryvoice.org

The three-year anniversary of the November 24, 2012, fire that killed 112 Bangladesh garment workers at the Tazreen Fashions Ltd., factory offers a time to reflect on garment workers’ ongoing struggle for workplaces where they will not be killed or injured and for jobs that will support their families.

The Tazreen fire was preventable, as was the collapse of the multistory Rana Plaza factory five months later in which more than 1,130 garments workers died and thousands more were severely injured.

Workers at Tazreen and Rana Plaza did not have a union or other organization to represent them and help them fight for a safe workplace. Without a union, garment workers say they are harassed and even fired when they raise safety issues with their employer. They are not trained in basic fire safety measures and often their factories, like Tazreen, have locked emergency doors and stairwells packed with flammable material.

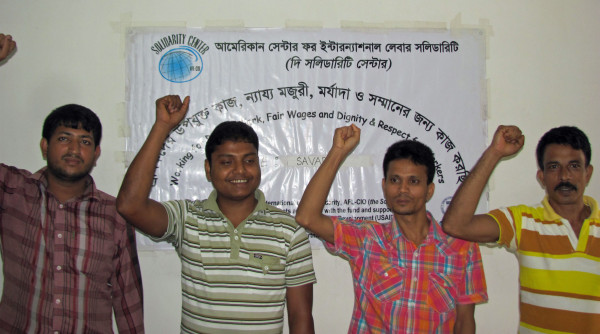

Despite the many obstacles to forming organizations and achieving a voice at work, garment workers are at the forefront of pushing for change at their factories. With our strong and long-term grassroots connections in Bangladesh, the Solidarity Center allies with garment workers to provide ongoing training for factory-level union leaders on topics such as gender equality, workers’ legal rights and fire safety.

This photo essay gives voice to the sorrow, but also the hope, of the 4 million workers who toil in Bangladesh garment factories.

1. Bangladesh’s 4 million garment workers, mostly women, toil in 5,000 factories across the country, making the $25 billion garment industry the world’s second largest, after China. Yet many risk their lives to make a living. In the three years since the fatal Tazreen Fashions Ltd. factory fire, some 31 workers have died and at least 935 people have been injured in garment factory fire incidents in Bangladesh. Credit: Law at the Margins

2. Some 112 garment workers were killed in a blaze that swept through the Tazreen factory on November 24, 2012. Hundreds more were injured and like Tahera (above), will never be able to work again. Survivors say they endure daily physical and emotional pain, and often cannot support their families because they cannot work and have received little or no compensation. Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

3. Tens of thousands of Bangladesh garment workers held rallies on May Day this year to highlight the need for the freedom to form worker organizations to ensure safe and healthy workplaces. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

4. With few jobs available that pay a living wage, more than 600,000 Bangladeshi workers migrate each year. Yet, “after two years, after three years, they are not getting their salary,” says Sumaiya Islam, director of the Bangladesh Migrant Women’s Organization (BOMSA). “After spending $1,000 (to labor recruiters), they are not getting paid.” Credit: Shahjadi Zaman

5. Migrants from Bangladesh also risk their lives when going overseas for jobs. In June, Bangladesh families rallied to demand the government punish traffickers after many Bangladesh workers were among migrants stranded on abandoned boats by unscrupulous labor traffickers. “I did not get anything to eat for 22 days and just survived by eating tree leaves,” Abdur said, describing his journey to Malaysia. Credit: Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

6. On April 24, 2013, the multistory Rana Plaza factory collapsed, a preventable tragedy that killed more than 1,100 garment workers and injured thousands more. On the two year anniversary in April, family members and friends gathered at the site of the building to commemorate their loss. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

7. Thousands of garment workers, like Mosammat Mukti Khatun (above, looking at the Rana Plaza rubble) who survived the Rana Plaza disaster, remain too injured or ill to work and support their families. Survivors and the families of those who lost loved ones in the collapse say they are struggling to make ends meet, unable to pay rent, send their children to school or provide for other basic needs. Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

8. Days before tens of thousands of Bangladesh garment workers rallied on the two-year anniversary of the Rana Plaza collapse, the ITUC released a report that found “a severe climate of anti-union violence and impunity prevails in Bangladesh’s garment industry. The violence is frequently directed by factory management. The government of Bangladesh has made no serious effort to bring anyone involved to account for these crimes.” Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

9. The Solidarity Center launched the Bangladesh Worker Rights Defense Fund in April 2014, following an increase in violence and harassment against workers who were seeking to form unions to protect their health and rights on the job. Donations of more than $15,500 helped to provide costly medical treatment for organizers beaten or attacked while speaking to workers about their rights, and temporary food and shelter for workers fired for trying to improve their workplace. Credit: Solidarity Center/Shawna Bader-Blau

10. Despite employer and government resistance to workers’ efforts to form organizations to improve job safety, in the Dhaka export processing zone alone, 40 of the 103 factories include workers’ welfare associations, which are similar to unions. Credit: Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

11. Women garment workers primarily fuel Bangladesh’s $25 billion a year garment industry, yet women are “still viewed as basically cheap labor,” says Lily Gomes, Solidarity Center senior program officer for Bangladesh. “There is a strong need for functioning factory-level unions led by women,” says Gomes, who is leading efforts to help empower women workers to take on leadership roles at factories and in unions throughout Bangladesh. Credit: Solidarity Center/Kate Conradt

12. With strong and long-term grassroots connections in Bangladesh, the Solidarity Center provides ongoing training for garment worker union leaders on topics such as gender equality, workers’ legal rights and job safety. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

13. Garment worker union leaders sharpen their skills through regular Solidarity Center workshops, such as this one on financial management. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

14. Hundreds of garment worker union leaders have participated in this year in the Solidarity Center’s 10-week fire safety certification course. “People who worked at Tazreen and Rana Plaza had no training and had no union,” says Saiful, who took part in a recent fire training. “This training is about making sure those things never happen again.” Credit: Solidarity Center/Rakibul Hasan

For three years the victims of the worst factory fire to hit the fashion industry in recent times have been waiting for compensation. Now, finally, hope is on the horizon.

Around 120 garment workers burnt to death and hundreds more were injured when flames engulfed the multi-floor Tazreen garment factory in Bangladesh on 24 November 2012.

Trapped behind locked exists, workers jumped for their lives from the upper floors of the building, with more than a hundred sustaining permanent, life-changing injuries.

Like thousands of garment factories in Bangladesh, the workers at Tazreen fashions were making clothes for global retailers destined for Western wardrobes.

IndustriALL Global Union, together with the Clean Clothes Campaign, C&A and the C&A Foundation have set up the Tazreen Claims Administration Trust to compensate victims for losing loved ones, loss of income and to pay for much-needed medical treatment. Claims are already being processed and victims can expect to receive payments in the coming months.

Brands and retailers with revenue over US$1 billion are being asked to pay a minimum of US$100,000 into the fund for victims.

Certain brands that sourced from Tazreen, including C&A, Li & Fung (which sourced for Sean John’s Enyce brand) and German discount retailer KiK have now paid into the fund.

But more brands must face up to their responsibilities and pay.

That includes Walmart, Tazreen’s biggest customer. The anniversary falls just as the retail powerhouse stands to profit from US$50 billion of consumer spending on Black Friday this week.

Other brands that sourced from Tazreen and have not paid are U.S. brands Disney, Sears, Dickies and Delta Apparel; Edinburgh Woolen Mill (UK); Karl Rieker (Germany); Piazza Italia (Italy); and Teddy Smith (France).

Three years have passed but we cannot let brands forget the victims of Tazreen. Now it is time for a measure of justice.

by Christina Hajagos-Clausen, Textile and Garment Industry Director at IndustriALL Global Union. IndustriALL Global Union represents garment workers around the world. It is one of the key drivers of the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety signed by more than 200 global fashion retailers and covering more than two million garment workers in 1,500 factories.

Photo credit: IndustriALL Global Union

I am sure that you have a closet overflowing with clothing. Chances are you might even have items that still have the swing tickets attached. Have you ever looked at the care label to see where your clothing was manufactured? Fast fashion isn’t going anywhere anytime soon. In fact fast fashion was created for this simple reason: to get us buying more and more and without much thought into where these garments are made.

I am hoping that by the time you finish reading this piece, something would have shifted. For one you will take a look at the care labels of your clothing and find out who is responsible for it and that you will hopefully reevaluate your shopping habits. Fast fashion companies cut corners, they use cheaper fabrics and cheap labor. It is simply exploitation. There is the argument that fast fashion creates jobs but when people are exploited it simply isn’t right.

Cape Town was aflutter recently when H&M (Hennes & Mauritz) opened its first store in South Africa. More stores are planned including Johannesburg’s Sandton City as well as others in Southern, East and West Africa.

It is always great to have brands open stores in our country, least of all when you know that jobs will be created. It is reported that about 600 jobs were created leading up to the opening of the V&A Waterfront and Sandton City stores. Staffers, around 60, were sent to Sweden for training. H&M plans to have as many as 1 500 people employed within the next 12 months.

The buzz continues but there is one fundamental problem with brands like these and it seems very few people know what really happens behind closed doors. In this case, behind the doors of the factories that produce these garments. This lack of knowledge was evident from the social media images from fashion bloggers to local personalities applauding H&M on their opening.

It was not long ago, in fact only two years prior, in April 2013 when the deadliest industrial disaster in the history of clothing manufacturing took place. The collapse of the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh, claiming the lives of 1 138 of its workers.

Two years after this tragedy, H&M is still behind on correcting the fire and safety hazards in its factories in Bangladesh according to the joint report released by the International Labor Rights Forum, Clean Clothes Campaign, Maquila Solidarity Network, and Workers Rights Consortium. These fire and safety hazards are the working conditions their workers are forced to work under making sure that fast fashion reaches our stores timeously. Repairs, which include installation of fireproof doors and the removal of locking or sliding doors from fire exits are some of the issues that have not been addressed.

These are repairs that affect the staff working in these factories. If not dealt with, it could have disastrous outcomes, like that of April 2013. It appears that more attention is placed on pushing out the orders as opposed to the people who make these garments. Will these factories get away with these hazardous conditions if they were in developed countries? No! Cheap labor is simply that; cheap. Bangladeshi workers who sew for H&M toil in extremely dangerous conditions. So can you really say that their fashion is cheap? Cheap in price definitely but costly on the scale of human lives. Par Darj, the country manager for H&M South Africa described H&M’s merchandise as “democratic fashion” high quality, easy and affordable for people who ordinarily might not be able to buy fashion. How democratic is this model if H&M chose to open their first store at the V&A Waterfront? The only people who benefit from the fast fashion system are the executives who are some of the richest people in the world.

The H&M store in Cape Town is 4700 square meters and is said to be one of their biggest stores in the world. Rumor has it that there might be a section carrying local designers in the near future. Could this be why they are exploring the feasibility of opening a local manufacturing facility? Par Darj said H&M already has a production factory in Ethiopia, opened in 2014. “We will see what is possible in South Africa”. One would hope that the working conditions in this factory are safer than the one in Bangladesh or the potential of a factory opening in South Africa will not cost anyone their life.

Are South African malls in the future only going to comprise of top international brands? The likes of Burberry, Forever 21, Top Shop, Zara etc. It could be, unless you reevaluate your shopping habits.

The True Cost film will make you rethink your fast fashion addiction. I can’t help but think of the interview with Shima Akter, a 23-year-old Bangladeshi garment worker who was beaten by her factory supervisors for organizing and leading a workers’ union in the hopes to get better working conditions ‘I don’t want anyone wearing anything which is produced by our blood.’

I encourage you to watch The True Cost to understand just where your clothing comes from and the price others are paying for it.

Who Makes Our Clothing? | Livia Firth | The True Cost

My name is Jessmin Begum, I am 31 years old and I have been working in the garment industry for 15 years.

I have worked in six different factories in total. In those 15 years, I have seen many different labels. I have manufactured clothes for brands such as H&M, Gap, Walmart, S.Oliver, C&A, Zara. I first started working in the garment sector after completing my Higher Standard Certificate of education. A neighbour told me about a job in a garment factory; so I joined. In my first job I was a ‘helper’. That means I was cutting the threads from the seams of the clothing. I did that job for a month and then I was promoted to a seamstress. I worked in that factory for one year. Then I got a job at another factory where the salary was higher. I worked in that factory for the next nine years and earned 7700 Taka (85€/£62/$96) including overtime.

That factory was in an Export Processing Zone (EPZ). In the EPZ, a different labour law applies. The Government regulates it through an authority called BEBZA (Bangladesh Export Processing Zones Authority). My first job had been outside EPZ. You can tell the difference. They pay wages in a timely manner on the seventh day of the following month, they give regular weekend breaks and holiday pay.

The government ruled that each factory in the EPZ should have a Workers’ Welfare Committee. When it came to the election for that committee, my friends encouraged me to run. They made posters and banners. The committee is comprised of 12 members. When it came to the election of the chair, the other eleven didn’t want to take on that role, so I did it. The committee is elected every two years and I was re-elected twice.

My duty as chair was to meet with BEBZA. Sometimes they came to the factory, which meant I had to leave my work and go to meet them at the General Manager’s office.

The factory owner put me under pressure.

In order to make a good impression, the factory owners told the Authority that they could speak to me at any time. However, I was pressurised not to go by the factory owner, the middle management, my line manager and supervisors. So I asked the people at the BEBZA why they called on me during working hours as my manager did not want me to leave my work.

Before I explain what happened, I would like to tell you a bit more about the factory

The factory had five floors and on each floor there were 400-500 people, around 2500 workers in the building, out of which there were just 12 committee members appointed. We were all working on different floors and in different jobs. During lunch break, we would sit together and discuss peoples’ complaints. We gathered information. When BEBZA came, sometimes we all went to see them, but often I went alone to pass on the complaints.

I was the one who was speaking out.

The others didn’t do that as much. BEBZA used to listen to me. They usually came two to three times a year as a routine check up, and when the workers were protesting.

So, as I said, the factory owner pressured me not to leave work in order to go to these meetings. When the time came for the meeting, they would give me more work. If I normally had to complete 10 garments, they now gave me 15, which would be impossible to finish. So sometimes I couldn’t attend the meetings. If there were no committee representatives who could attend the meetings with BEBZA, they asked the factory owner to send other employees, so he would send a supervisor or one of his relatives.

Whenever I had the opportunity to pass on the workers’ complaints, BEBZA said they would look into the problem. But there was no action. No solution. The law in Bangladesh stipulates working hours from 8am to 5pm, with two hours of overtime from 5pm to 7pm. But the owner pressurised us to work four or five hours of overtime. But you know, we can’t go home every day at 10pm. First of all, there is a security issue for women. Then, when we go home, we still have to cook. At that time I was living with my mother. I was single and my mother cooked for me. But other workers needed to do all that alone, they had to take care of their children and they also had to sleep.

The Authority did not respond to our complaints. There was no action.

So the workers gathered together and wrote the following demands: higher wages, no more than two hours of overtime per day, no insults while working, no beatings and, most importantly, no termination of our employment because of the strike. The last point was particularly important to us, because otherwise they could just fire us.

As the chair, I had a certain amount of power. There were 2500 workers supporting me. The first strike was on 9 February 2003. We told the management and the police that we would continue our strike and our attacks if they did not meet our demands. So they signed.

During my time as chair, we held four protests in total. After the first protest they couldn’t fire me anymore, so they looked for other ways to get rid of me. I was bribed with 200,000 Taka (2200€/£1650/$2570) by the factory owner. He teased me, gave me a bundle of money and said sarcastically:

“Girl, you don’t know how much money is in here. Just take it and go.”

They wanted me to leave the factory because I talked too much. They knew that I had influence. They knew the risk. They knew that if I went to the Authority, they would listen to me. I did not accept the money.

During the last strike, I was four months pregnant. One day I was injured by brick which I blocked from hitting my body with my hand. Workers were throwing bricks inside the factory and the police were throwing them threw back. I finally stopped working at the factory when I gave birth to my baby because I had to breastfeed. I couldn’t be fired when I was pregnant of course, but I resigned because of the baby.

Afterwards I worked in another factory outside of the EPZ for one and a half years where I wasn’t paid on time. I joined the National Garment Workers Federation in 2008 where I work part-time as the Secretary for Women’s Affairs. Now I am in the NGWF I am letting people know about the law and their rights.

I go out on the road a lot and visit workers in their homes. I also work in a factory as a production reporter where I earn 15.000 Taka. At least if I lose my job at the factory, I will still have the job at NGWF .

Unions are important because they encourage the factory owners to listen to us.

If the owner has a tight shipping deadline, he will talk to the union members and say “can you help me out, can you work two more hours” and they will accept. So the conversation begins.

Translated from the original interview in German by Anna Holl which appeared in N21

Translated from the original interview in German by Anna Holl which appeared in N21

My name is Arifa Sultana Anny. I am 19 years old. I have worked in the garment industry for two years and six months. A month ago I lost my job because I opened my mouth too wide.

I worked six days a week at the factory. Every day from 8am until 5pm. On most days, I worked overtime from 5pm to 10pm as well. Then I would be in the factory for 14 hours. Sometimes I also had to work on a Friday, so I did not have a day off during the week.

I got up every day at 6am, got ready and did the daily errands. I had to cook and keep the house clean. At 7.40am I went to the factory.

In the factory, it was an ordeal. There were five floors and each floor only had two toilets which were not even clean. 400-500 people were working in the factory. There was no doctor, no canteen and no prayer room. We supplied clothes to brands such as ZeroXposur (American outdoor brand) and Li and Fung (a $20 billion global sourcing firm that supplies 40% of all apparel sold in the US). I was working on the production of jackets and my job was a Checker. After the jackets had been sewn, it was my task to check for errors. If I found a mistake, I went to the person who had worked on that stage of the garment so that they could correct the mistake. For this job I got paid less than the seamstresses.

I was constantly put under pressure

If I overlooked a mistake and the line managers discovered it, they would tell me that I’m not doing my job well. If the line managers found a mistake, they made me suffer. They docked hours from my attendance record for which I was not paid, even though I had worked.

One day I heard about the National Garment Workers Federation (NGWF) and through them I learned about labour unions. So I wanted to form a labour union in my factory. To do this, you need the support of 30% of the workers.

When I raised the subject for the first time and my colleagues heard that I wanted to start a union, they initially feared threats from their manager and were afraid of losing their jobs. I worked every day. I spoke to the other workers during their lunch hour, after work and in their homes. And sometimes the workers said “no” so I explained to them again why we needed to form a labour union and often that no became a yes.

When the factory owners heard that I had joined the NGWF and wanted to start my own union, they began to put me under psychological pressure. It started with them giving me too much work and then sometimes they docked my wage.

One day I received a message to see the Quality Manager in his office who threatened to throw me out.

He said: Do you know how we will do it? We will bring clothes and cut the seams and say this is the quality that you have produced.

They said that I had to give up on the idea of a union and, if not, they would carry on with the torture and pressure. They threatened that I could no longer live in my home. They threatened to go to my landlord and tell him to throw me out.

The owners and other senior staff were not quite sure if I would really form a union. Of course, I did not confirm their suspicions. But I did not agree to stop it. I had the support of 100 workers for the union. I needed only fifty more to reach the required 30%.

The factory where I worked was called Elite Garments and the owner has a second factory called Excel.

One day the Quality Manager took me into the “Chamber” the room of the foreman and other senior managers. He told me that he would relocate me to the other factory. However, I did not want to be relocated because I had already started establishing the union within my factory. All the work would have been in vain.

It came to a point where the Quality Manager said I should beg before his feet not to be transferred. Three or four people were in the same room and enjoyed the show. Before their eyes, I went on my knees and held the feet of the manager. They all took pictures. They laughed at me, criticised me, insulted me. The work in the factory went on. No one outside the room knew what had happened. I did that for three hours. Then they let me go with a warning not to start the union. However, up until this point they still did not know one hundred percent if I would really form a union.

After this incident I knew, of course, that I was not the only one who suffered in the factory. So I could not stop. I had 100 people who supported me. I had begged on my knees to the manager so that the union could become a reality.

Why should I give up after I had come this far?

Later I got the missing 50 signatures. I had a form on which I collected the signatures of the workers which I got from the NGWF. When I had the 150 signatures, I brought the form to the NGWF and from there it went for confirmation to the Labour Office of the Government. When the Quality Manager heard about it the hostility increased. There was even more pressure. They insulted me at work. Then one day they took me by force to sign on a sheet of white paper. Then they threw me out of the factory. I was unemployed.

But the form to set up a labour union was already submitted. That is why people from the Labour Office came to the factory; they wanted to confirm the union. Of the 150 signatures, I had selected ten people for a committee. Five of the ten had already been fired and the rest were too scared to say anything. They did not speak. The government representatives asked the Quality Manager and the Production Manager what had happened to the five workers. They replied that the five had left of their own accord. And the government represenatives believed them. They knew from the NGWF that the workers had been fired, but they decided to believe the managers, and so the union was rejected. It seems the people from the Labour Office support factory owners rather than labour unions. We do not know, maybe they were bribed.

Now there is no trade union at the Elite factory because I no longer work there. This all happened a month ago. For the last month, I have received no income.

I had begun to work in the textile industry because my father was ill. When I entered 10th grade, two years before graduation, he became very ill, so it was time for me to find a job. Obviously I did not get a good job. A neighbour told me about a textile factory in the area, so I applied there and I got the job. It was ok for me. I didn’t find a better job.

When I worked, I earned 6600 Taka (75 € or £55) excluding overtime and from 1500 to 2000 (about 22 € or £16) for the overtime. I live with my parents and my three siblings. We live together in one room in Kilga, Dhaka. We cook on the gas stoves of two security guards who guard the building across the street. We share the toilet with five other families.

My three sisters go to school. Before I could pay their school fees with my salary – that was 2000 taka per month (22 € or £16). This room cost us 3,000 taka (33 € or £25) a month. My mother works as a maid and earns 3,500 taka (40€ or £29). My father can not work because he is ill. Even when I was working, the salary was not enough because I had to spend all the money on food, rent and school fees. If someone got sick, we had to take out a loan. It was never enough.

My mother is the only person who earns money now. After I lost my job, we had taken out a loan of 15000 taka (170€ or £125). In six months, I have to pay back nearly 20000 Taka (€227 or £167).

The factory owners become richer and richer, but with my salary I was not going anywhere. If I could earn 15000 taka (170€ or £125) a month for working in a garment factory, then I could live in peace and would not always be under pressure to pay bills.

I do not want to work in a factory. I’m trying to find another job but otherwise I will have to start working in a factory again. And I will still not be quiet. I must protest again. I am that kind of person. When I learned about the NGWF, I was the one who asked them questions. There are two kinds of people: those who see and accept corruption and the others who do not like it and fight it. I belong to the latter group.

I am proud to make clothes that people can wear anywhere in the world and in the West. It makes me proud that developed countries buy our clothes. I am so proud that you wear them.

At the same time, I also wonder why the Western countries do not pay us a decent wage for our work? Why don’t they support us? I want the middlemen to pay more to the factory for our clothes so the factory owners can pay more to the workers.

In Bangladesh, the textile industry is very important and with this industry we can improve the situation in our country. For this to happen, we need the help of the foreign people who buy our clothes. In return, I promise to make your clothes to the highest possible standard.

This is my promise.

You can follow Anna Holl’s travels to discover #whomademyclothes on our blog and on Twitter @hollanna Anna is reporting in Bangladesh for N21 who have a focus on textiles for the next 4 weeks. http://n21.press/schlagwort/textil/

Yesterday, the owner of the Rana Plaza factory complex and 41 other individuals were charged with murder.

In the hope that the justice system in Bangladesh will actually implement real punishment (and not succumb to internal corruption to invalidate the charges) and that the culprits will actually adequately pay for their crimes, the Twitter world has gone crazy in advocating real justice for the perpetrators, the offending big brands and even the consumers, highlighting that we are all somehow complicit in the bloodbath that was the Rana Plaza catastrophe in 2013.

Without wanting to take anything away from this eloquent and forward thinking conversation, the truth is that the big brands and the corporations are only one facet of the problem, and the reality is that there is another, unspoken abyss of so called ‘white labels’ selling unbranded clothes and accessories in vast quantities to smaller online retailers, to shops, to market stalls and even reputable fashion brands and boutiques all over the world.

These ‘white label’ sales are orchestrated by middlemen, tertiaries and distributors that are faceless, but who still peddle in misery, taking advantage of an unregulated system where the lack of transparency allows them to make massive profits and benefit from a convoluted and complicated supply chain that doesn’t safeguard workers and the environment, because there are no rules.

It goes two ways: just as the big brands cannot publish in full their supply chain contractors (and sub contractors) beyond first tier, mass producers have no way of knowing who they are selling to.

Many factory owners and brokers are unspeakably wealthy, have their own brands, often several, and many of their associates and partners operate also outside of the big brands by selling almost identical products to another invisible supply chain that we know nothing about because it is not branded, it is not part of the world of corporations and big brands, but it is nevertheless thriving.

To implement real justice, we need to understand that the issues are way more complicated than what we have been told so far, and that there are other culprits out there, who have been an intrinsic part in creating a system which is hell bent on exploitation and degradation.

For many years I was a designer with my own fashion label, and as such it was assumed that I would have the need to produce garments. I still receive dozens of emails from brokers and distributors, advertising the benefits of making cheap, high quality products through factories that I would never need to have a direct relationship with because they (the brokers and distributors) would look after it on my behalf.

I was, I still am, quite shamelessly, offered services that imply that I could grow my business rapidly, buying on trend, untraceable products, (onto which I could then apply my own label) to maximise my own profits. These emails come from companies operating from China, Bangladesh, Cambodia and Vietnam.

Premium brands, outlet stores and luxury boutiques are also taking advantage of this distribution stream, relying on the fact that their customer is no longer capable to discern a truly beautifully made piece from any old crap. This is even more sinister, as those brands and boutiques are able to achieve massive margins on a product that has cost them next to nothing.

How do we expose the fact that everybody is taking advantage of this rotten system badly in need of reform?

Of course major brands need to be accountable, and murder and ecocide are the correct words to be used to describe this scenario, but the fact is that we aren’t exposing the whole truth, because the whole truth goes deeper than anywhere we have reached so far.

The sad oxymoron of this industry right now is that the most scrutinised brands are also the ones that are investing the money and resources to actually begin to implement innovation (after all, they have a vested interest in innovating and saving their reputation), but for the health of this industry, we mustn’t stop at the big brands, but continue to question the industry and ensure that we take a much deeper look, at how we buy, who we buy from, why we continue to buy so much, and what are the real solutions to implement a positive change.

By the sheer power of their consumer visibility, the big brands and corporations should be held as an example (as I hope the owner of the Rana Plaza and his corrupt associates will be) but to put the blame solely on the household names doesn’t actually give a clear picture of the state of the industry as a whole.

What we are doing right now is to vilify a few, without exposing the rest of the problem, effectively ignoring a whole load of other actors, who are as culpable, but completely escaping our judgement.

We are letting them off scot-free.

Sure, it’s the obvious starting point, but by flagging the usual suspects we are giving them the opportunity to inject money, employ experts, and greenwash their operations, without exposing the system that has allowed them and so many others to behave abominably, outside of our scrutiny, just because we are less familiar with their names.

We need to keep advocating for governments to impose regulations, because voluntary codes of conduct are clearly not sufficient: it is only with the correct implementation of decent humane and environmental standards that we can change the fashion industry, and start to ameliorate this awful mess.