Texto por: Mari Barahona

Una prenda de vestir se compra, se usa una, dos o tres veces, ¿y luego? Esta es la pregunta que todos deberíamos hacernos más a menudo. Según las cifras publicadas por ONU Medio Ambiente y la Fundación MacArthur, una prenda se usa entre siete a 10 veces antes de tirarla a la basura o tenerla guardada. ¿Qué haces tú con la ropa que ya no usas?

Durante los tres últimos años, el comercio de ropa de segunda mano se ha multiplicado 21 veces más en el sector de la moda a nivel mundial, según los resultados del 2019 Resale Report de ThredUp. El mundo está cambiando rápido, las decisiones que la gente toma con relación al consumo de este tipo de prendas ha aumentado aceleradamente, en el 2016, el 45% del mercado ya compraba ropa usada mientras que en el 2019 subió a un 64%.

Según mencionado estudio, los consumidores de este tipo de ropa pueden adquirir variedad de marcas y precios desde prendas de moda de lujo hasta de tiendas muy económicas, el 33% de sus consumidores pertenecen a los Millennials (25 a 37 años), el 31% son Boomers (55 años y más), el 20% son de la Generación X (38 a 55 años) y el 16% restante pertenece a la Generación Z (18 – 24 años).

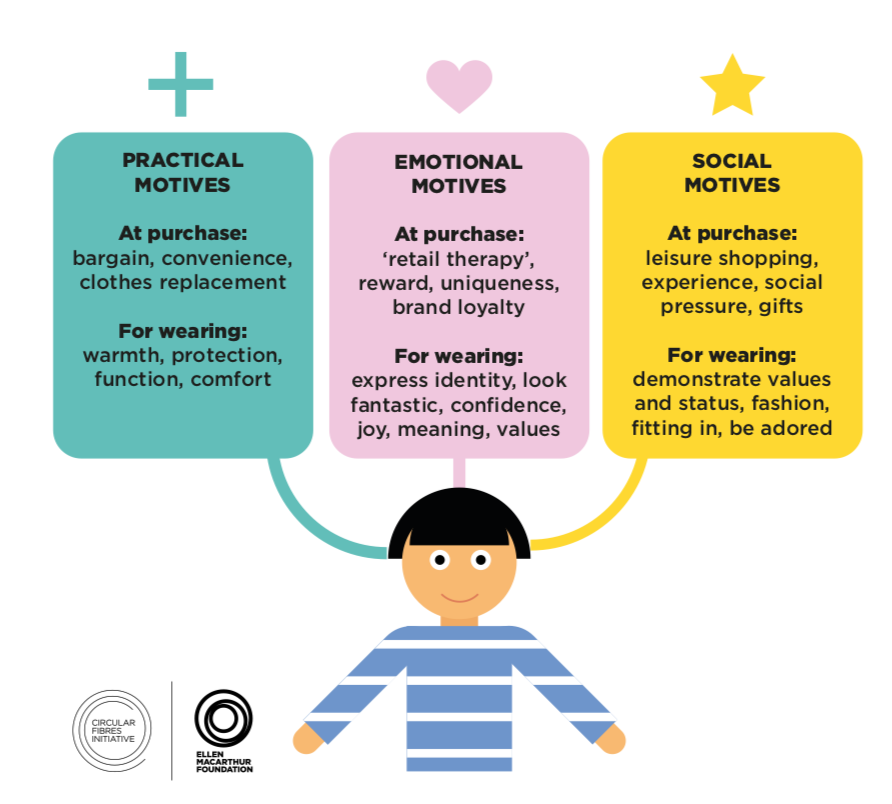

Cada vez son más las personas que apuestan por esta tendencia, además de hacerlo por temas económicos se han sumado otros factores como; nuevos hábitos y toma de conciencia, comprar una prenda usada reduce tu huella de carbono; además del acceso a páginas y aplicaciones para comprar y vender ropa mucho más fácil y más seguro.

En Ecuador ya se compraba y se vendía ropa de segunda mano. En la actualidad hay muchos lugares en donde se puede encontrar prendas en buen estado y excelente precio tanto en tiendas físicas como online. Según Carla Patiño, abogada ecuatoriana, “la mercancía de segunda mano que se comercializa en el país es la que ya está físicamente aquí, otras formas legales de adquirir esta ropa es mediante donación, venta o consignación”.

Pese a la creciente demanda de consumidores de ropa de segunda mano en el país, mediante la resolución No.182, publicada en el Registro Oficial No. 57 “está prohibida la importación de ropa usada y calzado usado” es decir, la importación de este tipo de ropa es ilegal y es un acto penado por la ley, aclara la abogada. Ecuador tiene una ventaja “saludable” en este mercado. En otros países la importación de bienes de segunda mano está teniendo graves impactos sociales y ambientales.

Patiño señala que el común denominador de las personas naturales y jurídicas que realizan esta actividad son: los contratos de trabajo, de acuerdo a la modalidad de freelance o servicios prestados, y el RUC autorizado por el SRI para poder facturar.

¿Comprar ropa usada es tan fácil como comprar ropa nueva?

Dependerá del consumidor, de sus gustos y de sus hábitos. Antes de donar o vender:

- Elige las prendas.

- Dales un vistazo extra, a veces son prendas que necesitan algún arreglo, todavía las puedes utilizar.

- Revisa la ropa. ¡Lávala!

- Haz una lista de toda la ropa que tienes y ponle un precio. Sé coherente con lo que pidas.

- Empaca tus piezas

- Elige el lugar en dónde vas a vender. (Nifty, CircularQuito, Thrifteanduio, Anaquel, Hallados, ReShop, MegaModaEc)

Toma en cuenta que darle un segundo hogar a tu ropa y a tus accesorios es una muy buena idea, pero si empiezas a comprar mucha ropa de segunda mano, comienza a perder sentido y volvemos al sistema de compra y desecho en el que ya vivimos, la idea es llegar a ser un ciudadano más responsable y elegir qué y porqué se compra.

NOTA: Recuerda que comprar a empresas/marcas locales también es ser responsable y coherente a la hora de comprar, difundir y preferir lo hecho en Ecuador.

Tomorrow I will be joining eXXpedition to sail some 2000 nautical miles from the Galapagos to Easter Island as part of an all-female Round the World voyage to gather the first global dataset of microplastic and microfibre pollution. From Ecuador to Chile passing by Peru and Bolivia, we are sailing past the cultures and communities I studied for my MA in Native American Studies, and subsequently worked with for over 20 years with my brand Pachacuti.

The Andes mountains run down the spine of the Pacific coast of South America. Andean philosophy sees all individuals as being part of a community, an ayllu. Humans are not separated from the natural world; they are two parts of a whole, each dependent on the other and giving to the other through a reciprocal relationship which sustains the community. The ayllu does not have fixed physical borders but is formed from the complex interlinking of relationships and an understanding of the fundamental interconnectedness of my interests, your interests and the interests of plants and animals. The ayllu is a place of nurture and regeneration and is seen as the basic cell of life. People, plants, animals and the earth itself nurture and are nurtured in a symbiotic relationship.

In indigenous cultures around the world, and particularly within indigenous cultures in the Americas, it is common that nature speaks. Ecuador has drawn from its indigenous past and became the first country in the world to legally recognise the rights of nature in 2008. It has given nature back its voice.

Last week I talked to Zapotec textile artist and weaver Porfirio Gutierrez from Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca, who explained that in his culture’s traditional philosophies, the plants are just like us. His parents would take him up into the mountains to collect plants for dyes and his father would talk to him about how they needed to have respect for the plants and trees because they are alive, just like us, and no life is more important than the other. “These days when everything is fast, everything is chemical, everything is plastic, we are forgetting the principles of being a human being, the slow way of living, the growing of food, making a textile. To me it is really important to create a conversation around that and educate people, and re-educate people”.

As I worked on the research for this year’s Fashion Transparency Index, I saw company report after report, referring to the preservation of natural resources, but even in attaching the word resources to nature we are effectively commodifying the planet, protecting it to support ever-increasing productivity. When studying Quechua, I learnt that there is no word for possession in the language. You cannot say ‘I have’. Everything you have or possess – not just goods and resources but also power and authority – are instead either with you, or not with you, meaning you are the steward, not the owner. This way of thinking changes everything.

Our challenge this decade is to move beyond our currently destructive Western worldview which is tipping us into a climate crisis and a plastic pollution catastrophe, towards a fashion industry which integrates nature in a truly sustainable way. We need our legislators to learn from the law passed in Ecuador and restore a voice to the oceans, earth and all that live in and on them. We need brands and retailers to move from competitiveness to collaboration and from the commodification of natural resources to working alongside nature in all her diversity in a way that is respectful, renewable and regenerative. We need them to look at longer lasting value systems than profit, prioritising instead the protection of our ecosystems and the wellbeing of our communities. And as citizens who have lost touch with the reality of living in mutual nurture and interdependence with the natural world, we need to rebuild our connections with how our textiles and clothes are made, the slow way, in balance with plants, animals, earth and water.

I believe that transhistorical community value systems can present a powerful counterpoint to the logic of generating profit now and help us to once again rediscover the spirit of the ayllu.

We don’t know the true cost of the things we buy. The fashion industry supply chain is fractured and producers have become faceless. This is costing lives. Not just the mass loss of life we hear about when another disaster hits a garment factory, but the lives of individual artisans and garment workers who cannot support themselves in their own community and undertake perilous journeys in search of a better life.

Hundreds of thousands of migrant garment workers are employed throughout the fashion and textiles suppy chain, many of whom live in constant fear as they are working illegally. “They took us to the airport and left us there for three days. We couldn’t travel, because we didn’t have tickets. Armed gunmen, who we were told were from the armed forces, threatened us. We feared we would be shot if we continued to protest. We were then rounded up in a camp” reported a garment factory worker in Mauritius to the Clean Clothes Campaign.

Legal migration can be a spur for development, but in many cases, particularly when people move illegally, migrants face harassment and violence and often increased poverty. The fashion industry has the potential to generate sustainable livelihoods for artisans and garment workers around the world wherever they live, but this can only be done through fully traceable and transparent supply chains, backed up with regular monitoring.

The current lack of transparency in fashion supply chains makes it virtually impossible for consumers to know who made their clothes and accessories. Without knowing #whomademyclothes, how can we know in what conditions they were made?

At Pachacuti, we believe fashion needs to rediscover a traceable narrative. We have worked for three years as a pilot on the EU Geo Fair Trade project which has brought an unprecedented level of traceability to our supply chain. The project aims to provide visible accountability of sustainable provenance, both for raw materials as well as production processes.

This level of traceability data is far from easy to collect – it cannot be achieved by a few clicks on the computer – but it is essential to guarantee that our supply chain is as transparent as we can possibly make it. Despite the remoteness and inaccessibility of the region of Azuay where our Panama hats are woven, we traced the production of our hats back to the GPS co-ordinates of 154 of our weavers’ houses – not easy data to collect when only 45% of homes were accessible by road, located high in the Andes.

But it doesn’t stop there. Not content with tracing our Panama hats back to where they were woven, we then traced the straw back to the communities on the coast of Ecuador in Guayas province where it is processed. Next, a bumpy hour by truck from the nearest paved road, we mapped the GPS coordinates of each plot of land in the coastal cloud forest where the straw is harvested on community-owned plantations. The community has been working hard to protect their area of land and to increase sustainability and biodiversity in the area. They are now seeing a lot more toucans, armadillos and monkeys in the plantation.

Once established, the carludovica palmata plant can be cropped monthly for 100 years – surely one of the most sustainable sources of raw material imaginable. The plants also help to a prevent erosion and improve air quality. Our straw is gathered by 32 harvesters who form the Love and Peace Association – maybe a rather incongruous name for men who spend most of their lives wielding a machete! The straw harvesters are keen to point out:“We are producting oxygen for the world”

Our research for the Geo Fair Trade project took three years, including a 6 month period in Ecuador and four other field trips in order to collect social, economic and environmental indicators and track our Panama hats to their source. Our weavers are delighted that this research data helps correct a historical misnomer and Pachacuti’s panama hats can now be tracked back to their country of origin – Ecuador!

But geographic traceability is just one element of creating a transparent supply chain. Transparency also implies openness, honesty, communication and accountability. Regular, ongoing monitoring of the supply chain to measure both the social and environmental impact is essential if we are to claim that our products are truly sustainable.

In 2012 UNESCO declared that the art of weaving a Panama hat in Ecuador would be added to their list of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Intangible Cultural Heritage is a term used for knowledge, traditions and rituals which permeate the everyday life of a community, passed down through generations and forming an intrinsic part of their identity and culture.

However, the historic exploitation of weavers by middlemen means that this timeless skill is under threat as young people are searching for alternatives. This has led to the small, rural community where we work in Ecuador having one of the highest levels of migration in the country, with 60% of children having at least one parent living overseas. The destruction of family and community life has led to high rates of alcoholism, double the national rate of youth suicides and teen pregnancies are the norm.

We have heard so many desperately sad stories of people, including the children of our weavers, who are paying coyotes, human traffickers, to take them on the dangerous journey through Central America and Mexico, across the border to the United States. One of our weavers has a 15 year old daughter who walked most of the way from Ecuador to Mexico before paying a coyote to cross the remote, desert border. In the village where we work, almost the entire younger generation has migrated and women outnumber men by 7 to 1. In interviews conducted with our weavers, most of them had children living overseas and several of them did not even know in which country their children lived. Many emigrants will work for years to pay back the traffickers, often returning penniless to their own country.

Unlike the journey taken by most Panama Hats in the world, which pass through the hands of around seven different intermediaries (known as ‘perros’ or dogs due to their unscrupulous purchasing practices) Pachacuti works directly with our artisans in every step of the process, weaving, dyeing, blocking, finishing, to ensure that as much of the final value as possible remains in their hands.

Our work on the EU Geo Fair Trade project involved the collection of 68 social, economic and environmental indicators which enabled us to measure our Fair Trade impact, tracking progress over a three year period. We also piloted the WFTO Sustainable Fair Trade Management System and Fair Trade Guarantee System. Prices are monitored through interviews with a sample group of weavers to ascertain a local living wage. The price is also measured against the government’s cañasta básica vital, the monthly market price of meeting basic needs for a family of 4 and we ensure that the prices we pay are rising at a higher rate of inflation. We provide ongoing training and investment, not just in design development and skills, but in self-esteem, human relations, building a nursery, costing of products and overheads and health and safety.

Since 1992, we have worked to preserve and encourage traditional hat weaving skills in Ecuador but, despite our efforts, hat weaving is still in steep decline in the wider community and the average age of our weavers is 58. As well as working to ensure this way of life is viable for future generations, last year we provided a substantial interest-free loan to help establish a new organisation to work specifically with younger weavers.

The art of creating Panama Hats is woven into the fabric of daily life in rural Ecuador: women weave on the bus, walking to market, on their way to the fields. For the women who weave Pachacuti Panama hats, weaving is more than an art, more than a skill, it is a way of life and represents the cultural heritage of an entire community. Will the art of panama hat weaving die out as young people abandon traditional, rural ways of life and migrate to the city, or emigrate in pursuit of the American dream? Or can Panama hat weaving provide a sustainable form of income to enable women to remain within their rural communities, keeping families together, and passing on their culture and traditions. Pachacuti is working to prove that the a better Panama hat industry is possible.

Fashion Revolution aims to raise awareness of the effect of our purchasing decisions on the livelihoods of garment and accessories producers and their communities. We believe that transparency is the first step in transforming the industry and is a way to bring wider recognition to the many skilled artisans within the fashion supply chain. This, in turn, will help ensure their work is properly valued and justly remunerated in the future.

If you want to help build more open and connected fashion supply chains, take a selfie and contact the brand on social media to ask #whomademyclothes?

Yesterday, in the small town of Gualaceo, Azuay, in Ecuador, the art of ikat weaving was officially recognised by UNESCO as intangible cultural heritage.

Intangible Cultural Heritage is a term used for knowledge, traditions and rituals which permeate the everyday life of a community, are passed down through generations and form an intrinsic part of their identity and culture. The skills are essential to the cultural identity of the community and the cloth is both practical and richly imbued with symbolic meaning.

Other forms of cultural expression which have already received this designation include Chinese acupuncture, Spanish Flamenco and, also in Ecuador, the art of Panama hat weaving. Whilst Material Cultural Heritage is clearly visible, the concept of Intangible Cultural Heritage is harder to understand as it embodies an art or a skill of great value to the country, often one in urgent need of safeguarding. Ikat weaving is a skill which is sadly in danger of extinction if steps are not taken to preserve it, and so its designation by UNESCO is hopefully a step to greater recognition of its importance nationally, as well as internationally.

Ikat is a Malay-Indonesian term, which is common to many cultures around the world, including Argentina, Bolivia, Ecuador, Guatemala and Mexico. Ikat is a resist technique where a resist to the dye, traditionally cabuya cactus fibre in Ecuador, is tightly wrapped around the warp before dyeing the yarn to create a pattern that will appear later during the weaving. It is a rare technique as the pattern needs to be held in the weavers head to ensure that the wrapped parts of the warp will translate into the correct pattern on the loom.

In the 25 years since I first visited Ecuador, natural dyes have all but died out in the country. On my first trip it was normal to see people dyeing wool with cochineal, indigo or nogal (walnuts). On my last visit to Gualaceo, I was delighted to see that a variety of natural dyes were still being used by the ikat weavers.

Traditional backstrap looms are still used where the weaver sits on the floor, although for textiles over 75cm in width, a foot pedal loom is often used. The pedal loom I saw in Gualaceo was cleverly constructed from old bicycle wheels!

Ikat is extremely labour intensive and requires considerable experience to memorise the complex patterns which need to be tied into the warp and which, when combined with the weft, magically transform into a pattern. According to one weaver, there are only around 15 ikat weavers left in the Gualaceo region.

In Ecuador, it is commonly known as a macana and the shawls which have long been a part of traditional dress are called Paños de Gualaceo. For centuries, the macana or paño de Gualaceo has been a key element in the traditional dress of the women in Azuay province, alongside the Panama hat, an embroidered blouse and two skirts, including an undergarment whose lower embroidered edge shows underneath the outer pleated skirt. Increasingly, I see a generational divide. In Sigsig where we work, very few young women wear traditional dress.

The three weavers pictured below are part of our Panama hat weaving association. I bought a whole roast pig for our group of 160 weavers in celebration of Panama hats being recognised by UNESCO as Intangible Cultural Heritage in December 2012.

The ikat shawl is not only beautiful and part of the rich textile heritage of the region, it is also an incredibly practical accessory. Women use it to carry their purchases home from market, or they carry their baby on their back. This mother, part of Pachacuti’s weaving association, is selecting straw for weaving her hats for the following week whilst keeping her child secure on her back.

One significant change in men’s dress in Ecuador over the past 50 years has been the disappearance of ikat ponchos, echoing the disappearance of this traditional textile technique. In the 1940s both wool and cotton ikat ponchos were worn in a traditional indigo blue and white. In the late early ’90s, indigenous Otavalan men dress underwent a Western revolution, partly due to the money pouring into the region as a result of the popularity of Ecuadorian chunky knitwear. With more disposable income, many men opted to exchange their white pleated shirt, white cotton trousers, alpargata shoes, poncho and felt hat, for jeans, trainers and a T-Shirt.

In addition to the near disappearance of ikat in traditional dress in Ecuador, its popularity has declined globally due to the prevalence on the high street of cheaper clothing with an ikat print. These garments are often called ikat by the brands who do not distinguish between a piece of cloth taking hours to weave by hand and embodying an incredible degree of skill and knowledge and a piece of cloth woven on an industrial machine.

In an article on cultural appropriation Refinery 29 recommends:

So, instead of going to a mall store and paying $7 for a cheap knock-off, go to the source. Know the story behind the piece, know the artist, what tribe they’re from, why the specific designs were used. It puts the power back in the hands of the marginalized group. Importantly, buying from a Native person or company also economically benefits the artist and the tribe, rather than a company that’s knocking off their designs.

In other word, make sure you know #whomademyclothes. Buy clothing with integrity, with a story, with a face behind it.

Hopefully the new UNESCO recognition will help to safeguard this dying skill and ensure it plays a part in the future textile heritage of Ecuador.

To find out more about intangible cultural heritage in need of safeguarding, visit UNESCO .

My name is Delfina Minchala Guaman, age 79 and 4 months. I am very proud of being almost 80. I am one of the five founding members of the Cañari Panama hat weaving Cooperative.

I was born in Guapan, Cañar. I was born here and I will die here. My father and mother wove hats to support their four daughters. I am the youngest of the sisters; the others are all deceased. When I was one year and six months old my mother died and my father alone supported us with the income from his weaving. He taught me to weave when I was six and I was paid 10 sucres (USD $0.75 cents, about 50p) for each hat. At age twelve I asked a friend to teach me how to weave fine hats so that I could earn 20 sucres per hat.

I married my neighbor when I turned 18 and we had 10 children together. We were very much in love and he was handsome. I am now widowed. Five of my children have died and the five surviving children are all professionals living in La Troncal (a town in the same province). They are two doctors, a nurse, a police officer, and one works in the Ministry of Culture. I have 16 grandchildren ranging in age from 8 months to twenty-two years old. Apart from weaving, I earn money raising cuy (guinea pigs). I have more than 60 cuy. I also have five roosters, three chickens, one dog, and one cat.

Pachacuti work with Delfina’s weaving cooperative