The sea. It is a sea upon which wars have been fought, across which goods and slaves have been traded, across which we have journeyed for centuries to exploit ‘new’ lands, decimate indigenous populations with our diseases and return with their treasures, and across which we are sailing today to investigate ocean plastic pollution.

The sea. Writers and poets speak of the silver sea, the lonely sea, the audacious sea, the sublime sea…. The plastic sea doesn’t have quite the same ring to it, yet that is one of the predominant qualities of the sea in this area of the South Pacific, and the reason why we are making this voyage south from Galápagos to Rapa Nui, Easter Island. We will be sailing into the South Pacific Gyre where the world’s predilection for plastic is at its most visible.

As we sail with two thousand miles of blue before us, we will experience many faces of this mercurial sea.

On our first day at sea, an hour out of harbour, we passed the meeting of currents which had split as they passed around San Cristóbal and were rejoining on the other side of the island, tracing an almost glass-like, curvilinear track between deeply furrowed verges.

CURRENT, in navigation, courans, (currens, Lat.) a certain progressive movement of the water of the sea, by which all bodies floating therein are compelled to alter their course, or velocity, or both, and submit to the laws imposed on them by the current. An Universal Dictionary of the Marine 1769. And therein lies our challenge on this voyage. How to bring velocity to a cultural current to move behaviour and habits faster around plastic pollution?

On the first night, the sea slooshed companionably against the hull and its undulating voice lulled us into the gentlest of womb-like sleeps until we are woken four hours later for our next watch. The midnight watch is my favourite. I walked up the companionway steps into a dark starscape. (No-one on board knows why a ship’s corridor is called a companionway as, on SV TravelEdge at least, it is barely wide enough for two people to pass) The moon sat like a luminous saffron saucer on the table of the horizon.

On the second night, the sea whispered conspiratorially and lured us with the glittering phosphorescence of a billion plankton. A shoal of flying fish were visible as white flashes of leaping light to starboard and the brightest of shooting stars illuminated the night sky.

On the third day we tangoed across the waves and eddies, our white ruffled line tracing a course across the deep blue dancefloor. Sea sickness set in amongst many of the crew as the sea roiled and seethed with a short swell and science was postponed in the hopes of a return to a kinder ocean tomorrow.

WAVE, a volume of water elevated by the action of the wind upon its surface, into a state of fluctuation. Definition from An Universal Dictionary of the Marine, 1769. We start asking ourselves, what are the actions we can take as a multidisciplinary crew to build momentum, to agitate, to sweep away resistance and create an unstoppable wave of change?

On the fourth day the swell lengthened, so we twice dropped the Manta Trawl off the spinnaker pole for half an hour each time. The contents of the trawl were passed through three sieves of increasingly fine mesh. Several Men o’ War but no visible plastic.

On the fifth day we made our first drop of the Niskin Bottle. I watched it plunge down into the unfathomable depths of the ocean, astonished by the clarity of the water as the rope extended to its full 25 feet. We whispered ‘Find the Niskin’ as we deployed the messenger weight, known on board as the golden snitch, which triggers the Niskin to close. These samples will be sent back to the lab in Plymouth to analyse how the types and quantities of microplastics in the subsurface compare to the surface water and will be the first global dataset of its kind.

On the sixth day Maggie, our first mate, hoisted metal buckets up the Mizzen mast. These will be left there for 311 nautical miles to determine whether microplastics are being transported by winds.

As the voyage continues, the wind drove us on towards our destination, with scurrying clouds and a seething sea painted a hundred hues of blue, green, grey and white. We pitch and roll. Sleep is difficult as the sheets and rigging rattle overhead and we slide into the leecloth or hull, depending on whether our bunk is port or starboard. We pass the 1000 mile mark – halfway through our voyage. Our night watch is spent creating a humorous poem about our voyage and crew based on the Beaufort Scale, which rates wind force from 0 to 12, although we have only experienced up to Force 6 to date.

Ten days into our voyage. Every mile brings us nearer to the gyre and ever trawl brings up an increasing amount of plastic: translucent filaments which coil inside our sample bottles; flecks of blue, green, white, too small for the AFTR on board so these will need to be analysed back in the lab in Plymouth; a black mesh, still pending analysis.

Thirteen days into our voyage the sea gods smile on us and the sea is almost eerily calm as we enter the South Pacifiic Gyre. We have sailed over 1700 miles and are in one of the remotest areas of the Pacific Ocean, nearing the most remote inhabited island in the world. We spend the morning and afternoon dropping the manta trawl and Niskin and analysing the results. We are shocked at what we find: our trawls within the Gyre bring up five times more microplastic, microfibres, and film than the total of all the other trawls we have carried out outside the Gyre on this voyage.

Almost every watch continues to bring its moments of awe at the sublime beauty surrounding us: the evening a school of pygmy killer whales played in our bow waves; the pinks, purples and oranges the sun paints the clouds as it sets a little later every evening on our journey south; and this morning when we saw a bright flash of rainbow suspended in a cloud at sunrise. The rainbow is a symbol of hope the world over which transcends the scientific explanation behind this regularly occurring phenomenon formed by the meeting of sunshine and water.

And herein, perhaps, lies the pathway towards finding an answer for our challenge. We need to engage people around the world in the fight to preserve the beauty and biodiversity of our oceans. We need to use the groundbreaking science we are collecting on board as a tool, but also engage people in an emotional response to the problems of plastic pollution.

A little over 200 years ago, the great explorer and scientist Alexander Von Humboldt travelled through Latin America. The Humboldt Current is named after him, an upwelling current bringing nutrients up from the deep but also bringing with it some of the tide of plastic which makes its way into the South Pacific Gyre. Humboldt’s scientific method encompassed art history, poetry and politics but in the intervening years scientists have pursued ever-narrowing areas of expertise.

The crew on board this eXXpedition voyage has been selected for our multidisciplinary set of skills and we need to work together to rediscover a multidisciplinary approach. In a world where we tend to draw a demarcation line between science and the arts, the subjective and objective, we need to reconnect science with our emotions, because we only protect what we love. I would like to think that this morning’s rainbow is nature’s way of telling us that there is hope for our oceans if we can find ways to make people around the world fall back in love with the science and poetry of this boundless deep blue sea.

During the month of February, we’ve been exploring fashion’s impact on water and looking at how we can practice water stewardship through our wardrobes. So far, we’ve discussed the consequences of industrial dyes, misconceptions around water consumption, and better laundry habits to conserve water. Now, we’re taking a look at how our wardrobes affect our oceans when they release microfibres.

What are microfibres?

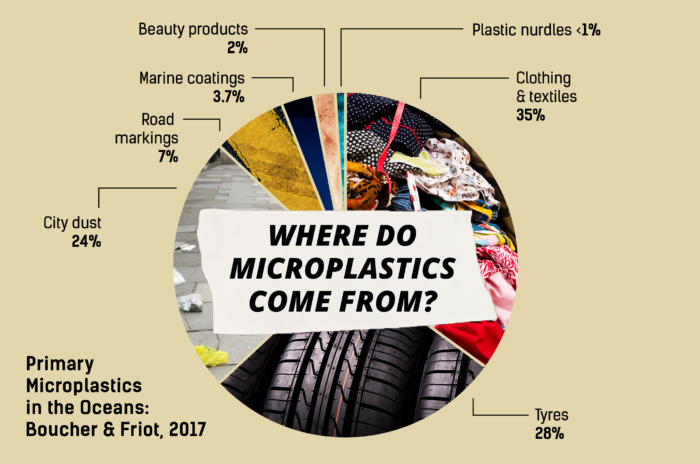

Microplastics are tiny plastic pieces that are less than <5 mm in length. Textiles are the largest source of primary microplastics (specifically manufactured to be smaller than 5mm), accounting for 34.8% of global microplastic pollution [1]. Microfibres are a type of microplastic released when we wash synthetic clothing – clothing made from plastic such as polyester and acrylic. These fibres detach from our clothes during washing and go into the wastewater. The wastewater then goes to sewage treatment facilities. As the fibres are so small, many pass through filtration processes and make their way into our rivers and seas.

Around 50% of our clothing is made from plastic [2] and up to 700,000 fibres can come off our synthetic clothes in a typical wash [3]. As a result, if the fashion industry continues as it is, between the years 2015 and 2050, 22 million tonnes of microfibres will enter our oceans [4].

What impact do microfibres have on the environment and on human health?

Due to the tiny size of microplastics, they can be ingested by marine animals which can have catastrophic effects on the species and the entire marine ecosystem.

Microfibres can absorb chemicals present in the water or sewage sludge, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and carcinogenic Persistent Organic Pollutants (PoPs). They can also contain chemical additives, from the manufacturing phase of the materials, such as plasticisers (a substance added to improve plasticity and flexibility of a material), flame retardants and antimicrobial agents (a chemical that kills or stops the growth of microorganisms like bacteria). These chemicals can leach from the plastic into the oceans or even go straight into the bloodstream of animals that ingest the microfibres. Once ingested, microfibres can cause gut blockage, physical injury, changes to oxygen levels in cells in the body, altered feeding behaviour and reduced energy levels, which impacts growth and reproduction [5][6]. Due to this, the balance of whole ecosystems can be affected, with the impacts travelling up the food chain and sometimes making their way into the food we eat! It has been suggested that people that eat European bivalves (such as mussels, clams and oysters) can ingest over 11,000 microplastic particles per year [7].

What can fashion brands do?

The fashion industry needs to take responsibility for minimising future microfibre releases. Brands can have the most impact if they take microfibre release into consideration at the design and manufacturing stages. Designers should consider several criteria in order to minimise the environmental impact of a synthetic garment [3]:

- Use textiles which have been tested to ensure minimal release of synthetic microfibres into the environment.

- Ensure the product is durable so it remains out of landfill as long as possible

- Consider how the garment and textile waste could be recycled, to achieve a circular system.

During manufacture, there are several methods that can be applied to reduce microfibre shedding such as brushing the material, using laser and ultrasound cutting [4], coatings and pre-washing garments [1]. The length of the yarn, type of weave, and method for finishing seams may all be factors affecting shedding rates. However, much more research from brands needs to occur in order to determine best practices in reducing microfibres and create industry-wide solutions.

Waste-water treatment…

Waste-water treatment plants (where all our used water gets filtered and treated) are currently between 65-90% efficient at filtering microfibres [6]. Research and innovations into improving the efficiency of capturing microfibres in wastewater treatment plants is essential to prevent them escaping into our environment.

Washing machine filters…

Improving and developing commercial washing machine filters that can capture microfibres may allow for an additional level of filtration, whilst also educating consumers and businesses [8]. However, current filters which need to be fitted by the user, such as that developed by Wexco, are currently expensive and reportedly difficult to install. They also place a financial burden upon the consumers, rather than pressurising brands to commit to change. To tackle this, we need more industry research and legislation to ensure all new washing machines are fitted with effective filters to capture the maximum amount of microfibres possible. However, we then have the issue of what to do with the microfibres once we have caught them – an area which requires more research and industry collaboration.

Collaboration is key

Collaboration across multiple industries is required if we are to tackle microfibre pollution. In addition to material research, waste management and washing machine research and development, there is a role for other sectors such as detergent manufacturers and the recycling industry to come together to help reduce microfibre pollution. Cross-industrial agreements could help promote collaboration between industry bodies and promote sharing of resources and knowledge.

A major issue has been a lack of a standardised measure of measuring microfibre release. However, a cross-industry group, The Microfibre Consortium recently announced the first microfibre test method. The launch will enable its members (including brands, detergent manufacturers and research bodies) to accelerate research that leads to product development change and a reduction in microfibre shedding in the fashion, sport, outdoor and home textiles industries. The Microfibre Consortium also works to develop practical solutions for the textile industry to minimise microfibre release to the environment from textile manufacturing and product life cycles.

The need for microfibre legislation

Comprehensive legislative action is needed to send a strong message and force the brands to address microfibre releases from their textiles. This is a complicated issue that will require policymakers to tackle this issue on many different levels and sectors. Currently, there are no EU regulations that address microfibre release by textiles, nor are they included in the Water Framework Directive.

However, there have been several developments in microfibre legislation in the past few years:

- As of February 2020, Brune Poirson, French Secretary of State for the Ecological and Inclusive Transition, is the first politician in the world to pass microfibre legislation. As of January 2025, all new washing machines in France will have to include a filter to stop synthetic clothes from polluting our waterways. This makes France the first country in the world to take legislative steps in the fight against plastic microfibre pollution. The measure is included in the anti-waste law for a circular economy.

- In 2018, US states of California and Connecticut proposed legislation which would see polyester garments legally required to bear warning labels regarding their potential to shed microfibres during domestic washing cycles. However, this legislation is yet to be passed.

- In 2019, the EAC urged the UK government to accelerate research into the relative environmental performance of different materials, particularly with respect to measures to reduce microfibre pollution, as part of an Extended Producer Responsibility scheme. However, the UK government rejected the proposal stating that current voluntary measures are sufficient.

What can you do?

Write to your policymaker

It is vital that policy is put into place to tackle microfibres, such as the new French washing machine filter legislation. If you are concerned about microfibres, we encourage you to write to your policy representative and urge your government to take action on microfibre pollution. Now that France has enacted the microfibre legislation, it raises the bar for other governments to also take action, but they will only do so with enough pressure from the people they represent – you!

Changing your washing practices

The easiest thing you can do to minimise microfibres releasing from your clothing is to simply wash your clothes less. Given that up to 700,000 microfibres can detach in a single wash [3] ask yourself if that item really needs to be washed or can it be worn once or twice more before you do?

While some research suggested using a liquid detergent, lower washing machine temperatures, gentler washing machine settings [3] and using a front-loading washing machine [9] can reduce microfibre shedding. Researcher Imogen Napper stated they found that there was no clear evidence suggesting that changing the washing conditions gave any meaningful effect in reducing microfibre release.

You can also use a Cora Ball, a guppy bag or a self-installed washing machine filter to capture microfibres from your clothing. The CoraBall and Lint LUV-R (an install yourself washing machine filter) have been shown to reduce the number of microfibres in wastewater by an average of 26% and 87%, respectively [10]. Although these can’t solve the problem, we still want to divert as many microplastics as we can from entering our waterways.

Should we all switch from synthetic fibres?

While many people’s first instinct is to switch from synthetic materials to natural materials to minimise microfibre release, this is not always a simple choice as there are other sustainability aspects involved. The UK’s Environmental Audit Committee in their report states ‘A kneejerk switch from synthetic to natural fibres in response to the problem of ocean microfibre pollution would result in greater pressures on land and water use – given current consumption rates’ [11].

Demand brands to do more to take action on microfibres

“Ultimate responsibility for stopping this pollution, however, must lie with the companies making the products that are shedding the fibres.” states the Environmental Audit Committee [11], but there are still too many major fashion brands not taking responsibility for what happens in their supply chains and in the life cycle of their products. As well as demanding action from your policymaker, we should also ask brands what they are doing to minimize the microfibre release from their products. It is clear that there is still a lot of work to do, and as their customers, we have a lot of power in influencing the impacts of the brands we buy.

The impacts of microfibres on the environment can be mitigated, but only with systematic and meaningful change supported by policymakers, brands, industry, NGOs and citizens all working together.

References

[1] Boucher, J. and Friot, D. (2017). Primary Microplastics in the Oceans: A Global Evaluation of Sources. IUCN. Available at: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2017-002-En.pdf

[2] Textile Exchange (2019). Preferred Fiber and Material Market Report. Available at: https://store.textileexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/woocommerce_uploads/2019/11/Textile-Exchange_Preferred-Fiber-Material-Market-Report_2019.pdf

[3] Napper, I. and Thompson, R. (2016). Release of synthetic microplastic plastic fibres from domestic washing machines: Effects of fabric type and washing conditions. Marine Pollution Bulletin. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X16307639?via%3Dihub

[4] Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2017). A new textiles economy: Redesigning fashion’s future. Available at: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/A-New-Textiles-Economy_Full-Report_Updated_1-12-17.pdf

[5] Koelmans, A., Bakir, A., Burton, G. and Janssen, C. (2016). Microplastic as a Vector for Chemicals in the Aquatic Environment: Critical Review and Model-Supported Reinterpretation of Empirical Studies. Environmental Science & Technology. Available at: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.est.5b06069

[6] Henry, B., Laitala, K. and Grimstad Klepp, I. (2018). Microplastic pollution from textiles: A literature review. Consumption Research Norway SIFO. Available at: https://www.hioa.no/eng/About-HiOA/Centre-for-Welfare-and-Labour-Research/SIFO/Publications-from-SIFO/Microplastic-pollution-from-textiles-A-literature-review

[7] Van Cauwenberghe, L. and Janssen, C. (2014). Microplastics in bivalves cultured for human consumption. Environmental Pollution. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0269749114002425

[8] Browne, M., Crump, P., Niven, S., Teuten, E., Tonkin, A., Galloway, T. and Thompson, R. (2011). Accumulation of Microplastic on Shorelines Worldwide: Sources and Sinks. Environmental Science & Technology. Available at: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es201811s

[9] Hartline, N., Bruce, N., Karba, S., Ruff, E., Sonar, S. and Holden, P. (2016). Microfiber Masses Recovered from Conventional Machine Washing of New or Aged Garments. Environmental Science & Technology. Available at: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.est.6b03045

[10] McIlwraith, H., Lin, J., Erdle, L., Mallos, N., Diamond, M. and Rochman, C. (2019). Capturing microfibers – marketed technologies reduce microfiber emissions from washing machines. Marine Pollution Bulletin. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.12.012

[11] Environmental Audit Committee (2019). Fixing Fashion: clothing consumption and sustainability. House of Commons. Available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmenvaud/1952/1952.pdf

Research and writing by Sienna Somers, Policy and Research Co-ordinator at Fashion Revolution

In it’s 5th year and already the worlds largest fashion activism movement, Fashion Revolution was formed in response to the Rana Plaza factory collapse in Bangladesh in 2013, where 1,138 people lost their lives. Calling for greater transparency in the supply chain, workers rights and a re-think of the way we use and consume clothing, Fashion Revolution is a global campaign that champions an ethical and sustainable fashion industry.

As Novel Beings, now A Novel Approach, Khandiz and I have worked with Fashion Revolution to art direct and produce their branding campaigns for 2015 and 2016, but we knew the 2018 should be something slightly different. Not only should the tone be reflective and respectful of the campaigns origins, but it should also celebrate all the wonderful young people who have embraced the rally all to action and joined the fashion Revolution.

So in order to celebrate all the wonderful revolutionary consumers who have joyfully taken up Fashion Revolution’s cause over the last 5 years, we ran a competition to find the faces of the 2018 Fashion Revolution campaign. We were looking for passionate young people, all at different stages of their own personal Fashion Revolution, to fly the flag for us.

We were overwhelmed by the response and delighted by our final selection. From musicians to bloggers and fashion students, please meet the Faces of The Revolution.

Grace Fairweather

How did you first hear about Fashion Revolution and what inspired you to want to be the next ‘face’ of the campaign?

I first heard of Fashion Revolution through the incredible London-based brand Birdsong. Dazed Digital did an article on them a few years ago and, even though I was already interested in and attempting slow fashion, this is when I really started to commit to ethical and sustainable living. A few Google searches later, I had found Fashion Revolution and the endless inspiration and information they provide.

When I saw Fashion Revolution was looking for “faces” for their anniversary campaign, I jumped at the opportunity to model for an organisation I align with morally. I’ve existed on the periphery of modelling for a while now; doing odd shoots and jobs for fashion-based businesses, but have always been wary of taking a job that could mean compromising my personal ethics. This is the first time I’ve modelled for an exclusively “ethical” organisation, (Fashion Revolution) and agency (A Novel Approach) and it was an incredible experience!

What do you do when you’re not posing for Fashion Revolution?

Hello! First-and-foremost an English student, but I’m also a blogger, model, and freelance writer.

What changes in your shopping or self-styling habits has Fashion Revolution inspired you to make?

One of the great things about Fashion Revolution is that, as an organisation, they champion multiplicity. My slow fashion journey has taught me that there is no one-way to live sustainably and any path you do take has its own complications, moral and otherwise. My current favourite to shop sustainably is Depop. I’ve recently created my own concept shop on there as an extension of my blog, November Meets May. (@novembermeetsmay on Depop).

Do you have any advice for anyone who would love to ‘green up’ their wardrobe and join Fashion Revolution, but doesn’t know where to start?

Equip yourself with knowledge! Knowledge will be your best tool in deciding which green path is right for you. Watch the True Cost, read newspaper articles on the current state and statistics of fast fashion, and keep up-to-date with Fashion Revolution. My own journey was a slow one and you don’t have to do anything earth-shattering to be a part of the revolution. Making the decision not to shop fast fashion for 3 months, a month, even a week is a great start and will make more difference to your life and the lives of others than you realise.

What is your most cherished piece of clothing and why?

I have the most incredible vegan, pinatex (pineapple leather) jacket from a sustainable, LA-based brand called Pangean, with “Save the Planet” embellished on the back. It’s easily the piece I get the most comments and compliments on. Nothing makes me feel more badass.

What will you be doing for Fashion Revolution Week?

There are so many amazing events on this year that it’s hard to decide! Here in Exeter an ethical clothing store, Sancho’s Dress, is putting on a different event every day of the week, so I really am spoilt for choice. So far, I’m thinking of attending their “Meet the Makers” panel and sales event party, and then heading up to London for the Depop x Fashion Revolution event, as well as (hopefully) the Galdem x Fashion Revolution event.

Who is your style icon?

Janelle Monae and Willow Smith. Sorry, I couldn’t pick one!

Mao Miyakoshi

How did you first hear about Fashion Revolution and what inspired you want be the next ‘face’ of the campaign?

I heard about it for the first time in Japan a few years ago. I was so happy that we could have the opportunity to share more information of ethical fashion to Japanese people because ethical fashion is still isolated compared with the European market.

I arrived in London from Japan with a two year visa, I made a promise to myself that I will try things that I’m excited about, even if it feels impossible or makes me anxious because you never know what’s gonna happen.

When I saw the post for ‘Model Wanted’ for the Fashion Revolution campaign, I felt super excited and imagined how nice it would be if I’m in the shoot. But after 3 seconds, the doubt appeared. ” Don’t be silly, Mao. You don’t have anything. You are not as beautiful or have as nice a body as model; you’re short, not skinny. Of course it’s not for you. Model needs to be like model.” But I tried to change my mind, decided to give it a try, because nothing would change if I fail. I thought an Asian girl being in the shoot in Europe would be interesting, and seeing a model that’s short and non-skinny can encourage people who think they are not special. Also, at least I passed the applicant requirement that I am in UK and I could attend the shoot date, and I LOVE ethical fashion! Also, I wanted to have more connections with like-minded ethical people, so I’m so glad I applied!

What do you do when you’re not posing for Fashion Revolution?

I’m beginning my work as a fashion stylist. I have been building my portfolio and sending submissions to magazines. So far, my work has been accepted by two magazines, one in Germany and one in America! I would love to use my work to promote ethical fashion. I’m also a fashion assistant at the sustainable fashion brand COSSAC and in October I’ll be a MA Textile design student at Chelsea College of Art.

What changes in your shopping or self-styling habits has Fashion Revolution inspired you to make?

I haven’t bought new clothes that much in the last few years since I have been into ethical fashion. I have three older siblings, they and my mother give me lots of clothes and because I love fashion styling I’m always trying to figure out more ways to wear the clothes I have.

But Fashion Revolution has definitely given me more ethical shopping options and ideas for how to how we can treat our clothes nicely.

Do you have any advice for anyone who would love to ‘green up’ their wardrobe and join Fashion Revolution, but doesn’t know where to start?

I would suggest they choose the category that they are interested in the most, like clothes, accessories or lifestyle or cosmetics and then Google it. You can easily find nice opinions and articles from bloggers and you can pick some nice brands from them. But the important thing is not to get stressed and worried. Sometimes, people feel a duty to purchase sustainable products, even if they don’t like the design. The approach is not going to work in the end. The key is to enjoy yourself, and celebrate the ethical and environmental movement at your own speed.

What is your most cherished piece of clothing and why?

My checkered trousers are the no.1 useful piece in my wardrobe. It can transform any way I like, for a cool style, or pop style and always people asked me where I got them. I found them at flea market in Yoyogi Park in Tokyo and they cost only £3! Another favorite piece is the T-shirt that I wear in second picture. This was a surprise gift from a friend; the design is from my favorite illustrator Kazuo Hozumi. She remembers that I like his work and she bought it for me as soon as she saw it. Always receiving a gift makes me pleased, especially if it’s a surprise. It was double happiness.

What will you be doing for Fashion Revolution Week?

The brand I assist at COSSAC, will have a show room in the event ‘Ethical brands for Fashion Revolution’, so I will be there, but I’m also planning to attend several events as all event looks super interesting so it’s gonna be quite busy week for me.

I am planning to ask #whomademyclothes but haven’t decided on the brand yet, as soon I do I’ll share the photo on instagram.

Who is your style icon?

I don’t have a specific fashion icon. My mother was my first icon, but I am always inspired by the arts and all kinds of actresses, films and photography. My favorite films are Amèlie and Simple Simon. I like directors with a unique view of the world of like Jean Pierre Jeunet and Woody Allen.

Rachel Callender

How did you first hear about Fashion Revolution and what inspired you to want be the next ‘face’ of the campaign?

I was introduced to Fashion Revolution through a previous graduate from my university. Their work is very focused on sustainability and conscious design, actively questioning and challenging attitudes towards the waste the fashion industry produces throughout the design process.

Knowing that I wanted to learn more ways to be a sustainable and considerate designer myself, he sent me the link to Fashion Revolution and voila!

How has Fashion Revolution inspired your shopping or self-styling habits?

Before discovering the campaign I had recently stopped shopping high street brands and I certainly can’t afford to buy designer clothes with just my student loan! So charity, second hand and vintage shops were and are still my go to. What Fashion Revolution has taught me is the importance of considering the lifespan of your purchases. Now I am even questioning my charity buys and how they could be recycled at the end of their lives, depending on their fibre content.

What do you do when you’re not posing for Fashion Revolution?

I’m a Fashion Design: Menswear second-year student at Central Saint Martins.

Do you have any advice for anyone who would love to ‘green up’ their wardrobe and join Fashion Revolution, but doesn’t know where to start?

When buying ‘new’ items for your wardrobe, start at a second-hand shop! Try Mary’s Living and Giving stores, or ’boutique’ charity shops if you don’t want to work too hard to find something beautiful, as they offer a more curated selection of garments.

But I have personally found the best garments at the jumble sale style shops! You just have to be willing to look long and hard, but when you do you can snag yourself a bargain for your toil. Repairing loved garments, instead of throwing them away if they become damaged by darning and patching, can actually make them look even better and gives character to clothes. I personally love sashiko stitched patches to revive tired clothes.

What is your most cherished piece of clothing and why?

I have a ginormous sweatshirt I bought at Crisis in Finsbury Park, which I adore and barely ever take off. It’s a heavily faded shade of purple with a screen-printed illustration of a Vizsla dog on the front, which is also peeling and fading. It seems to have been a work sweatshirt for ‘Red Dog Films’. I don’t know why I’m so attached to it really; I think I just love the little Vizsla print!

Who is your style icon?

I honestly couldn’t say I haven’t had one of those for a while! Style influence, on the other hand, would be a combination of my mum and dad’s wardrobes.

What will you be doing for Fashion Revolution Week?

I will be making my own clothes! Sourcing fabrics and all components which will allow me to definitely answer the #whomademyclothes!

But a problem a lot of designers and makers have is that more fabric shops than I’d like to hold back information about their supply chain which makes it difficult to ultimately determine whether the fabrics were created in sustainable and ethical conditions. There definitely needs to be more transparency in fabric shops. The Cloth House in Soho is one of the better stores in London for transparency and product knowledge. And online you can find fantastic eco options at Offsetwarehouse.

Freya Joy

How did you first hear about Fashion Revolution and what inspired you to want to be the next ‘face’ of the campaign?

I have been following Fashion Revolution since I joined instagram. I’ve always really admired their work, It’s such an empowering movement and it’s so easy for you to join in, get your hands dirty and really feel like your contributing to something important; armed with nothing more than a spare five minutes and your smartphone. Having been applauding Fashion Revolution from a distance for so long, I leapt at the chance to be a part of the campaign. I’m so grateful to have had the opportunity to be involved in something that has influenced and inspired me so much.

How has Fashion Revolution inspired your shopping or self-styling habits?

I’m a charity shop addict. It can be so hit and miss and I love that, it kind of feels like modern day treasure hunting. There’s definitely a feeling of success I get when I find something I love in a charity shop that I don’t get in the same way when buying brand new clothes. I’d say that’s where everything I’ve learned from Fashion Revolution has affected me the most. Understanding where my clothes have come from and the impact their production has on the lives of the people who make them and on the environment has definitely given me a newfound sense of responsibility as a consumer that has really lit the fire under my existing charity shop enthusiasm!

What do you do when you’re not posing for Fashion Revolution?

I’m a Musician and I also work for Lush UK.

Do you have any advice for anyone who would love to ‘green up’ their wardrobe and join Fashion Revolution, but doesn’t know where to start?

My main piece of advice, or maybe reassurance would be that it’s much easier than you think. One of the facts that really stood out for me, from Fashion Revolution’s fanzine, “Loved Clothes Last”, is that by extending the life of your clothing by a further nine months, you can reduce the carbon, waste and water footprint by around 20-30% for each piece. With that in mind, learning simple tricks for how to care for different fabrics, or how to repair clothes instead of throwing them away when they show signs of wear and tear, become inspiring, revolutionary acts.

What is your most cherished piece of clothing and why?

That’s a very difficult decision to make! I have a lot of my mum’s and brother’s old clothes that I wear often and love mainly because they were theirs first. But it’s probably a vintage M&S blazer I acquired whilst volunteering in a charity shop in my hometown when I was fifteen. I still wear it a lot now, but back then I don’t think I left the house without it for about two years; I just completely fell in love with it. Working at the charity shop was probably the catalyst for how crazy I am about charity shopping now. So there is definitely an element of nostalgia and gratitude I feel towards that blazer, which would make it difficult for me to ever part with it!

Who is your style icon?

My style icon would have to be Nai Palm, lead singer of Hiatus Kaiyote. Much like her music, her style is wildly varied and inspired by a diverse range of cultures and influences. Not one to shy away from accessories, metallics and bold colours, she usually wears lots of ever-changing chunky, oversized jewellery.

In a beautiful interview she did a couple of years back for the Under The Skin project, she talks about how a lot of the jewellery she is drawn to comes from nomadic cultures, which, being an orphan who moved around a lot as a child, she identifies with. She also talks in the interview about how off the back of her aesthetic, people who aren’t familiar with her work often assume she is in a punk band, when in fact she is an R&B/Soul singer. I really admire how her style doesn’t conform to any particular ‘genre’, really it’s the amalgamation of everything that she somehow manages to make work together seamlessly, that in turn makes her look so authentic and enchanting. I think that’s a really unique and beautiful thing.

What will you be doing for Fashion Revolution Week?

I’ll definitely be asking some brands #whomademyclothes… It’s an important question to keep asking. And I’m planning to come to some of the London events.

__

Download our campaign images here and help spread the word about Fashion Revolution!

Oxford Dictionaries declared post-truth to be the international word of the year for 2016. The word was chosen to reflect the politics of the past twelve months. Truth has been relegated to a bit part on a stage where politicians appeal to emotions and feelings, rather than thoughts and minds.

Fashion Revolution is a pro-truth campaign.

A poem by Sasha Haines-Stiles in Fashion Revolution’s new zine Money Fashion Power concludes:

Who embroiders truth

Who’s naked underneath

Who are you

Who are you wearing?

Illustration by Alec Doherty

For Fashion Revolution, truth means transparency and transparency implies honesty, openness, communication and accountability. Transparency means that if human rights or environmental abuses are discovered, it is far easier for relevant stakeholders to understand what went wrong, who is responsible and how to fix it. It also helps unions, communities and garment workers themselves to more swiftly alert brands to human rights and environmental concerns.

In order to create a sustainable fashion industry for the future, brands, and retailers must start to take responsibility for the people and communities on which their business depends. The factories operating in the Rana Plaza complex made clothes for over a dozen well-known international clothing brands, but it took weeks for some companies to determine whether they had contracts with those factories, despite their clothing labels being found in the rubble. Lack of transparency costs lives. It is impossible for companies to make sure human rights are respected and that environmental practices are sound without knowing where their products are made, who is making them and under what conditions. If you can’t see it, you don’t know it’s going on and you can’t fix it. Tragedies like Rana Plaza are preventable, but they will continue to happen until every stakeholder in the fashion supply chain is responsible and accountable for their actions and impacts.

This week sees the inauguration of new US President Donald J Trump. The Washington Post called him ‘the least transparent U.S. presidential candidate in modern history’ due to his failure to release his tax returns or provide evidence for the tens of millions of dollars he has reportedly donated to charity.

At Fashion Revolution, we are working on compiling the next edition of the Fashion Transparency Index which will cover 100 of the major global fashion brands with a turnover above $1.2 billion. Ivanka Trump’s brand does not disclose her financials, but we thought it would be interesting to measure her transparency against the criteria we used for the 2016 index to see how she would score. Last year we rated and ranked 40 companies based on how transparent they are. Those who are more transparent get more marks than those who are less transparent. It uses a ratings methodology, which benchmarks companies against current and basic best practice in supply chain transparency in five key areas:

The lowest percentage scores in our 2016 index, were achieved by Chanel who scored just 10%, and Hermès and Claire’s Accessories who each scored 17%.

Measured against the same criteria, Ivanka Trump’s brand would have scored 0%. Her website discloses no information at all. Nothing.

Fashion Revolution’s mantra is Be Curious, Find Out, Do Something. We ask people to dig deeper, look for evidence, hold brands to account, ask them #whomademyclothes. The New York Times has carried out research into Ivanka Trump’s supply chain. According to a review of shipments compiled by import databases Panjiva and Import Genius, the latter of which tallied 193 shipments for the brand during 2016, her shoes and handbags are made principally in China, whilst her dresses and blouses are made in China, Indonesia and Vietnam.

Ivanka Trump’s website is post-truth. It’s not untruthful, but it appeals to the emotions of consumers to sell her clothing, rather than providing any facts. It claims to be the ultimate destination for Women Who Work, but what about the women who work for her in China, Indonesia and Vietnam? Her website contains no code of ethics, no supplier or vendor code of conduct, no sustainability or CSR report, no manufacturing list, no human rights or environmental policies. Nothing.

In the past month, critics of Donald Trump have taken to posting ironic reviews of Ivanka Trump’s Issa boots on Amazon.

On 13 December Lucinda Tinsman posted

Very narrow boots; go well with people with a narrow-minded outlook on life and actively the validity of people of diverse backgrounds from being worthy of civil rights. Because they are made of man-made materials, very difficult to breathe in. Due to the escalation of climate change they are linked to, in all likelihood the wearer will not be able to breathe at all within one generation. They are the product of pure greed, which doesn’t make any sense because even the wealthiest individuals’ children and children will die if their father’s and father’s father’s actions led to a world that cannot support human life, which is what is happening as we speak. Do not buy, for the good of the country or for the good of your children.

Susan Harper gave the boots a five star rating, explaining

The leather is perfectly conditioned with the sweat and tears of underpaid sweatshop workers, and will keep its beautiful sheen for years.

Without being truthful and transparent about how and where her clothes are made, Ivanka Trump can do little to refute disparaging comments about her supply chain. Yes, the reviews are ironic, but if Ivanka Trump had been more honest from the outset, she could perhaps have avoided significant reputational damage to her brand.

The Globescan Corporate Responsibility Radar 2016 found that transparency is a critical driver of trust in business; being seen as open and honest is the most significant driver of trust, yet consumers across the world rate the performance of companies poorly for “being open and honest.” Brands not only need to know their supply chain in detail, but this information also needs to be made available to the consumer in a way which informs and educates and starts to rebuild public trust in the fashion industry. Brands who practice transparency can help build customer trust and enhance their reputation at the same time as safeguarding the health and wellbeing of their workers and the environment.

As George Orwell said in 1984 ‘In a time of universal deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act’. So let’s see a revolution and let’s make transparency the word of the year for 2017.

On 24th April 2017, the anniversary of the Rana Plaza collapse, the second edition of our Fashion Transparency Index will be published. It will review and rank 100 of the biggest global fashion and apparel brands and retailers according to their level of supply chain transparency. Brands have been chosen on the basis of two factors: 1) voluntarily requested to be included; and 2) according to annual turnover, over $1.2 billion USD and representing a variety of sectors including high street, luxury, sportswear, accessories, footwear and denim from across Europe, North America, South America and Asia.

It still strikes me as profoundly wrong that even though cotton is the world’s oldest commercial crop and one of the most important fibre crops in the global textile industry, the industry generally fails to focus on the entire value chain to ensure that those who grow their cotton also receive a living income.

Up to 100 million smallholder farmers in more than 100 countries worldwide depend on cotton for their income. They are at the very end of the supply chain, largely invisible and without a voice, ignored by an industry that depends on their cotton.

When it comes to clothing, companies’ supply chain engagement was once limited to who their importer was. Now they are engaging with their supply chain more and have better awareness of the factories used to manufacture their end products. Even before the Rana Plaza disaster of 2013, there had been increased attention on improving the conditions experienced by textile factory workers thanks to campaigns such as the Clean Clothes Campaign.

Some companies also have awareness beyond the factories and these are all movements in the right direction. However, even those mindful of the difficulties faced by factory workers, tend to miss the first links in the supply chain.

Maybe this is because cotton farmers continue to somehow lose out in both the so-called ‘sustainable’ and ‘ethical’ fashion debates. When companies talk about ‘sustainability’ in their clothing supply chains, they are generally looking at the environmental impact of sourcing the raw materials. Meanwhile in ‘ethical’ conversations about the many livelihoods touched by the garment value chain, companies generally refer to factory workers, again overlooking the farmer who grows the seed cotton that goes into our clothing.

The reason we need to keep insisting that cotton farmers are an important part of the fashion supply chain is because cotton is failing to provide a sustainable and profitable livelihood for the millions of smallholders who grow the seed cotton the textile industry depends on. Just as it’s important for us to take home a living wage, to help bring a level of security for our families and the ability to plan for the future, I would argue that this is even more vital for people living in poorer countries where there is little provision for basic services such as health and education or the safety net of social security systems to fall back on.

As a global commodity, cotton plays a major role in the economic and social development of emerging economies and newly industrialised countries. It is an especially important source of employment and income within West and Central Africa, India and Pakistan.

Many cotton farmers live below the poverty line and are dependent on the middle men or ginners who buy their cotton, often at prices below the cost of production. And rising costs of production, fluctuating market prices, decreasing yields and climate change are daily challenges, along with food price inflation and food insecurity. These factors also affect farmers’ ability to provide decent wages and conditions to the casual workers they employ. In West Africa, a cotton farmer’s typical smallholding of 2-5 hectares provides the essential income for basic needs such as food, healthcare, school fees and tools. A small fall in cotton prices can have serious implications for a farmer’s ability to meet these needs. In India many farmers are seriously indebted because of the high interest loans needed to purchase fertilisers and other farm inputs. Unstable, inadequate incomes perpetuate the situation in which farmers lack the finances to invest in the infrastructure, training and tools needed to improve their livelihoods.

However research shows that a small increase in the seed cotton price would significantly improve the livelihood of cotton farmers but with little impact on retail prices. Depending on the amount of cotton used and the processing needed, the cost of raw cotton makes up a small share of the retail price, not exceeding 10 percent. This is because a textile product’s price includes added value in the various processing and manufacturing activities along the supply chain. So a 10 percent increase in the seed cotton price would only result in a one percent or less increase in the retail price – a negligible amount given that retailers often receive more than half of the final retail price of the cotton finished products.

Within sustainable cotton programmes, Fairtrade works with vulnerable producers in developing countries to secure market access and better terms of trade for farmers and workers so they can provide for themselves and their families.

Our belief is that people are increasingly concerned about where their clothes come from. This year we visited cotton farmers in Pratibha-Vasudha, India, a Fairtrade co-operative in Madhya Pradesh. We saw the safety net that Fairtrade brings; the promise of a minimum price that works in a global environment. The impact on prices of subsidised production in China and the US adds to unstable global cotton prices. These farmers democratically decide how the Fairtrade Premium is spent: on training to improve soil and productivity, strategies to mitigate the impacts of climate change and on the most important ways for their communities to benefit, such as building health centres and educating children.

Consumers want their clothes made well and ethically, without harmful agrochemicals and exploitation. We think about farmers when we talk about food. Let’s start thinking about farmers when we think about clothing too.

Image credits: Trevor Leighton.

Yesterday, the owner of the Rana Plaza factory complex and 41 other individuals were charged with murder.

In the hope that the justice system in Bangladesh will actually implement real punishment (and not succumb to internal corruption to invalidate the charges) and that the culprits will actually adequately pay for their crimes, the Twitter world has gone crazy in advocating real justice for the perpetrators, the offending big brands and even the consumers, highlighting that we are all somehow complicit in the bloodbath that was the Rana Plaza catastrophe in 2013.

Without wanting to take anything away from this eloquent and forward thinking conversation, the truth is that the big brands and the corporations are only one facet of the problem, and the reality is that there is another, unspoken abyss of so called ‘white labels’ selling unbranded clothes and accessories in vast quantities to smaller online retailers, to shops, to market stalls and even reputable fashion brands and boutiques all over the world.

These ‘white label’ sales are orchestrated by middlemen, tertiaries and distributors that are faceless, but who still peddle in misery, taking advantage of an unregulated system where the lack of transparency allows them to make massive profits and benefit from a convoluted and complicated supply chain that doesn’t safeguard workers and the environment, because there are no rules.

It goes two ways: just as the big brands cannot publish in full their supply chain contractors (and sub contractors) beyond first tier, mass producers have no way of knowing who they are selling to.

Many factory owners and brokers are unspeakably wealthy, have their own brands, often several, and many of their associates and partners operate also outside of the big brands by selling almost identical products to another invisible supply chain that we know nothing about because it is not branded, it is not part of the world of corporations and big brands, but it is nevertheless thriving.

To implement real justice, we need to understand that the issues are way more complicated than what we have been told so far, and that there are other culprits out there, who have been an intrinsic part in creating a system which is hell bent on exploitation and degradation.

For many years I was a designer with my own fashion label, and as such it was assumed that I would have the need to produce garments. I still receive dozens of emails from brokers and distributors, advertising the benefits of making cheap, high quality products through factories that I would never need to have a direct relationship with because they (the brokers and distributors) would look after it on my behalf.

I was, I still am, quite shamelessly, offered services that imply that I could grow my business rapidly, buying on trend, untraceable products, (onto which I could then apply my own label) to maximise my own profits. These emails come from companies operating from China, Bangladesh, Cambodia and Vietnam.

Premium brands, outlet stores and luxury boutiques are also taking advantage of this distribution stream, relying on the fact that their customer is no longer capable to discern a truly beautifully made piece from any old crap. This is even more sinister, as those brands and boutiques are able to achieve massive margins on a product that has cost them next to nothing.

How do we expose the fact that everybody is taking advantage of this rotten system badly in need of reform?

Of course major brands need to be accountable, and murder and ecocide are the correct words to be used to describe this scenario, but the fact is that we aren’t exposing the whole truth, because the whole truth goes deeper than anywhere we have reached so far.

The sad oxymoron of this industry right now is that the most scrutinised brands are also the ones that are investing the money and resources to actually begin to implement innovation (after all, they have a vested interest in innovating and saving their reputation), but for the health of this industry, we mustn’t stop at the big brands, but continue to question the industry and ensure that we take a much deeper look, at how we buy, who we buy from, why we continue to buy so much, and what are the real solutions to implement a positive change.

By the sheer power of their consumer visibility, the big brands and corporations should be held as an example (as I hope the owner of the Rana Plaza and his corrupt associates will be) but to put the blame solely on the household names doesn’t actually give a clear picture of the state of the industry as a whole.

What we are doing right now is to vilify a few, without exposing the rest of the problem, effectively ignoring a whole load of other actors, who are as culpable, but completely escaping our judgement.

We are letting them off scot-free.

Sure, it’s the obvious starting point, but by flagging the usual suspects we are giving them the opportunity to inject money, employ experts, and greenwash their operations, without exposing the system that has allowed them and so many others to behave abominably, outside of our scrutiny, just because we are less familiar with their names.

We need to keep advocating for governments to impose regulations, because voluntary codes of conduct are clearly not sufficient: it is only with the correct implementation of decent humane and environmental standards that we can change the fashion industry, and start to ameliorate this awful mess.

Since we launched nearly a decade ago, every piece that is crafted by Aravore is signed by the person in our Atelier who made it. Aravore was in fact conceived as a way of challenging the way fashion is produced by focusing on the human dimension behind the art of fashion making. Our efforts went into making the supply chain as transparent as possible and on taking responsibility and employing directly –rather than sub-contracting- every person that makes each Aravore piece.

So, I was delighted to be asked to write this post and introduce you to two of the incredibly talented ladies that make up our main Atelier in Asuncion, Paraguay. The work that the Fashion Revolution campaign is doing to raise awareness about the human faces behind the labels is incredibly important and we are very proud to be able to support it by sharing a little bit of our story and the people behind it.

Revitalising Traditional Techniques & Approaching Manufacturing from a Different Perspective

When we launched our very first capsule collection, back in 2005, we presented 10 monochrome knitwear pieces made out of unbleached organic cotton. Given that there was no colour variation, we had to make sure that each piece had something to offer in terms of texture and style.

Basic hand crochet is a skill that is generally available in Paraguay, where our main Atelier is based. However, only three or four types of stitches are generally known and used locally to make more or less the same patterns and types of products. We wanted to change that and innovate by bringing new materials, designs and adding new dimensions to this traditional technique.

At Aravore, we make kidswear and we wanted the pieces to have a touch of nostalgia –and crochet was perfect for that! But we also wanted the products to feel contemporary. So, over the years we have been very experimental with materials, colours and shapes, always aiming to create something fresh and surprising. We mixed some hand crochet detailing with knitting in order to add variety to the stitches and because of the lacey quality that crochet has, that immediately makes a piece look and feel delicate and more ethereal.

Our approach to manufacturing is also a little different from a standard workshop or factory floor –where each worker generally specialises in a small part of the process. We chose instead to empower each individual maker by giving them the tools and knowledge to be able to make a whole piece from start to finish. This might not be the best approach in terms of productivity or speed, but the daily innovation that goes on in our Atelier would not have been possible otherwise. Indeed, each one of the knitters and seamstress have had a role in making this possible, by actively contributing with their ideas and talent to the continuous experimenting that goes on in our studio. Below, I’d like to introduce you to two of them.

Introducing Alba, Aravore’s own crochet magician

In the short clip below, you can see Alba’s amazing hands at work. Alba heads the Aravore team of crochet technicians at our main Atelier in Asuncion – and you can see why! She is simply incredible and her technique, impeccable. But the best thing about Alba is her energy and enthusiasm.

Alba is 34 years old and the mother of a lovely little girl. She learnt to crochet from her mother, as most girls would have traditionally done in Paraguay. Since joining Aravore in 2006, Alba has also been trained in house in all other parts of the process of making clothes, from design to quality control, learning about materials and understanding why it was important for us to choose the organic yarns that we use at Aravore and the special care that working with these materials requires. However, her “first love” is still crochet:

“What I love most about crochet is that it allows me to put together and build whole garments from scratch. I like the feeling that as I crochet, I am also shaping and putting together a whole piece.”

Alba, Aravore’s head of crochet

There is indeed something very tactile and emotional about knitwear and about creating a piece of knitwear. We get attached to our knitwear in a way that we don’t always do with other pieces of clothing. Perhaps this is because there is something slightly raw and basic about knitwear that brings us closer to the origin of clothing, by emphasising textures and the yarns that are used to make it and this in turns, brings us closer to the hands of its maker.

Meet Blanca Lila, Aravore’s Head Seamstress

Blanca is a 41 year mother of two wonderful kids and her family’s sole breadwinner. She joined Aravore to assist with the cleaning of our first Atelier back in 2006. Back then, Blanca had no background in textiles or fashion, however she was keen to learn and we encouraged her to take advantage of the free courses we offered in house. She took our advice in her stride and took every single in-house course that we offered. She showed so much interest and applied her enthusiasm so successfully that she is now fully proficient in all aspects of clothes making from pattern cutting to sewing and hand finishing. In fact, she has worked so hard and so purposely at improving her skills that she is now our head seamstress!

“I begun by learning about the washing and ironing processes that come at the end of the production process. Then I started learning about fabrics, yarns and the different sewing machines we had at the Atelier. Once I was able to sew and put a garment together, I begun learning about pattern cutting. And I want to keep on learning! I want to continue developing my pattern cutting skills and learn also some new skills. I want to continue going forward, always.”

Blanca Lila, Aravore’s Head Seamstress

Over the last decade, Aravore has trained directly over 40 women in different aspects of fashion making, from design to knitting, pattern cutting, couture sewing techniques and quality control. Many of them are still working at Aravore, others have gone on to open their own Ateliers and even to launch their own brands. Aravore is structured and run as a self-funded social enterprise and every penny made through the sale of our products goes back into the company to pay for fair wages, social security benefits and training of all of the ladies at our Atelier and satellite ateliers that we also support.

During the first trade show we did back in 2005, people were incredibly moved to find that you could learn a little bit about how each of our pieces was made and who made it, simply by looking at the labels. We hadn’t fully realised till then, what a novel concept this was and how detached we had become from understanding what goes on behind the products we purchase.

Today, we are encouraged by the fact that, a decade on, the concept of identifying the person behind each garment in the label is no longer such a novelty. However it is still far from being the norm and we hope that perhaps in another decade it might become so. Till then, we will continue to contribute with our efforts -even if at a small scale- towards the achievement of a true fashion revolution, one where we have reconsidered and understood the real value of the materials we use, where we have rethought the methods we use to manufacture and have begun to fully appreciate the skills, effort and aspirations of the people behind the labels.

*Yanina is the Co-founder, Designer & Creative Director of Aravore. She is also an Associated Consultant for different organisations including the London College of Fashion and is a Non-Executive Member of the Board of “A Todo Pulmon”, Paraguay’s largest re-forestation NGO. To learn more about Aravore’s story, visit www.aravore.com.