“We believe art remains a step ahead and guides where fashion goes” Simone Cipriani, Head and Founder of the Ethical Fashion Initiative.

Inspired by the paintings of Pieter Bruegel and August Strindberg’s A Dream Play, a new play Elijah Green follows a divine spirit as it wanders through contemporary life. Despite unremarkable existences, the stories of the characters layer into a portrait of the interconnectivity of all humans, with each individual both the centre of the world and part of something they cannot comprehend.

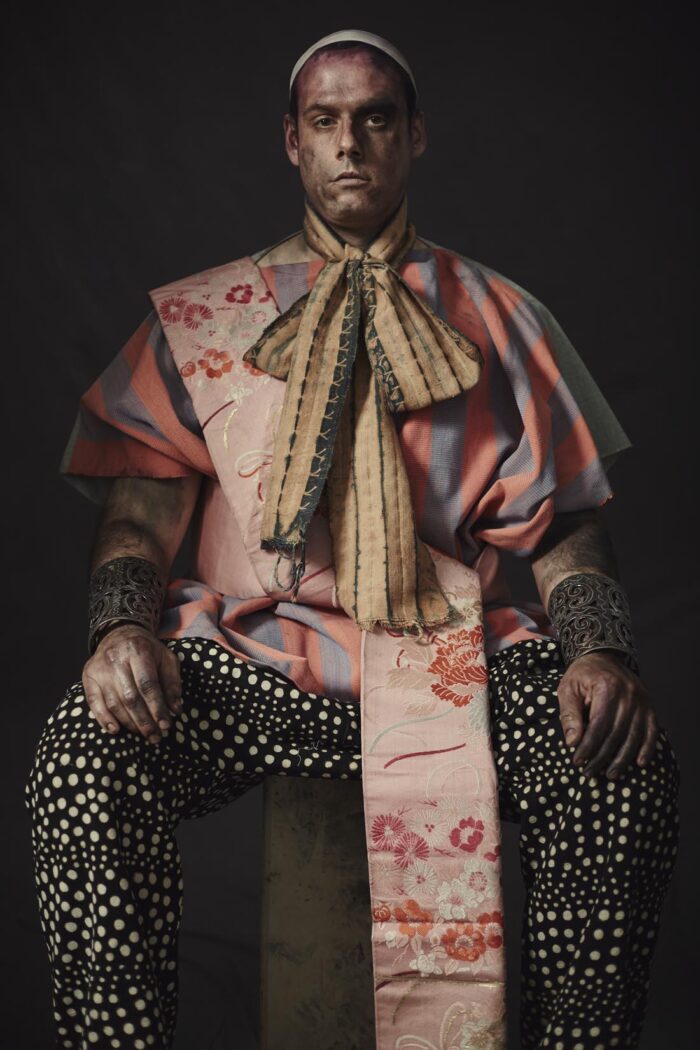

The writer, director and designer Andrew Ondrejcak has connected with artisans from Burkina Faso, Mali, Kenya and Haiti to create the costume collection for his upcoming play, in collaboration with the ITC Ethical Fashion Initiative. The costumes will feature hand-painted bogolan fabric from Mali, hand-woven danfani fabric from Burkina Faso, Maasai jewellery from Kenya and fer decoupé and papier-mâché accessories from Haiti.

Andrew Ondrejcak travelled with ITC’s Ethical Fashion Initiative to Haiti, Burkina Faso and Mali to meet with artisans and source fabric, jewellery, art and items to create the costumes and the play’s set. In Burkina Faso, Andrew Ondrejcak discovered fabric handwoven by women weavers and in Mali he received a crash course in the art of bogolan by master artisan, Boubacar Doumbia.

While in Haiti, Andrew Ondrejcak was able to meet with a wide variety of artisans to source latanier hats, papier-mâché accessories and tailor made metal drum pieces and many more. ITC Ethical Fashion Initiative also sourced traditional Kenyan Maasai jewellery and samples of Kenyan crafts.

Produced by Tanya Selvaratnam and Tommy Kriegsmann/ArKtype, Elijah Green will premiere on 10 March 2016 at The Kitchen in New York. The play will be showing at 8pm from March 10-12 and 17-19. In addition, Andrew Ondrejcak will do a post-show Q&A with costume collaborators from EFI and Alba Clemente on March 17th. Find out more

About ITC Ethical Fashion Initiative

The Ethical Fashion Initiative is a flagship programme of the International Trade Centre, a joint agency of the United Nations and the World Trade Organization. The Ethical Fashion Initiative works with the rising generation of fashion talent from Africa, encouraging the forging of fulfilling creative collaborations with artisans on the continent. The Ethical Fashion Initiative also enables artisans living in urban and rural poverty to connect with the global fashion chain. Under its slogan, “NOT CHARITY, JUST WORK.” the Ethical Fashion Initiative advocates a fairer global fashion industry.

Photo credits: Georgia Neirheim

Burkina Faso is the biggest African cotton producer and exporter, so it is no surprise that it boasts a strong textile heritage of handwoven cotton fabric, traditionally called Danfani. Stripes are the signature style of handwoven Burkinabé fabric however artisans are able to weave complex tartan and hounds-tooth fabric designs. Preparing the design on the loom itself can involve three to seven days of work depending on the complexity of the design. Artisans can weave on small and wide looms, the latter makes the fabric more attractive commercially as fashion & design buyers can do more with this larger fabric.

In Burkina Faso, the Ethical Fashion Initiative has worked to create a cooperative which links up several weaving ateliers. The introduction of wide looms and financing of capacity building workshops has also been central to the Ethical Fashion Initiative’s work of bringing brands like Stella Jean, United Arrows and Vivienne Westwood to work with artisans in this area of the world.

In this video, Italo-Haitian fashion designer Stella Jean travels to Burkina Faso with the Ethical Fashion Initiative to meet with handweaving artisans and source fabrics with local weaving ateliers to create her SS14 collection.

Since this visit, Stella Jean has used hand-woven fabric from Burkina Faso in each of her collections.

Many women used to weave on their own account, however many gave up because it was too difficult to sell their stock and make a living from it. Joining the weaving cooperative allows them to receive many more orders, work with others and improve their skills.

Most importantly, more orders means more income for them to take control of their lives. Clémentine, a mother of three children says that since joining the cooperative she has many more orders and “this means I earn more money which improves my life and the life of my family.” Clémentine was also recently able to purchase a motorcycle which makes her independent and helps her get from work to home.

Most women use the income they receive from the orders placed by fashion houses to give a better life to their children. Mamounata says that with the income earned “I can provide for my family and keep my bike in good condition.” Joséphine is able to feed her family with the money earned and has also managed to resolve some financial issues.

Some women had no background in weaving but decided to give the craft a chance to turn their lives around. For example Véronique used to collect sand and gravel to provide for her family. However, since she joined the cooperative she states that her life has changed because “I can now pay the school fees for my children, medical costs and food. In short, I earn enough to provide for my seven children.” Augustine used to cut wood and also collect sand and gravel to sell. She says that she rushed to join the cooperative as soon as she heard of it and says that “Frankly, my life is now much better. I have six children and I can cover all their needs.”

Learning new skills is very important not only to ensure fabric is woven to high standards but also for the confidence of the women artisans. Brigitte began weaving four years ago and since has learnt many weaving skills during this time. She now feels she truly has a profession because before “I didn’t know how to do anything.” Christine began weaving two years ago and says “My life is much better than before” – she now dreams to own a bike of her own.

The Ethical Fashion Initiative is proud to work with many women weavers from Burkina Faso who have been able to improve and take control of their lives through dignified work, producing fabric for luxury fashion houses.

Photo credits: Anne Mimault & ITC Ethical Fashion Initiative

Since leaving my job in London as a Fashion Editor to live in Cambodia and then Burkina Faso, my perspective on the fashion industry has been transformed.

It’s been 10 years since I worked for the Sunday Telegraph Magazine. Back then I cared more about style than where clothes came from. Now I’ve seen first-hand how garment factory workers in Phnom Penh live, and I’ve seen how factory-made imports have caused the demise of skills that were once at the core of African livelihood, identity and community.

Globalisation has changed the economies in Africa and Asia beyond recognition. Many are better off than before. Technology has thrown open the door for large-scale industry and mass-made products now flood the world for the benefit of us all. Or for some of us, anyway.

I have come to know some of the women who work in Asian factories and some who work in African villages. Rotha, age 21, is Khmer and lives in Phnom Penh – now a thriving industrial city and tourist hot spot. Ramata, 29, is Fulani and lives in sub Saharan Africa – better known for famine, desertification and conflict.

Young women like Rotha make up the majority of the workforce in the garment factories of Cambodia. Many of them, like Rotha have come from the countryside to work and earn an income for the family back home. She earns the minimum wage ($100 a month) and she sends as much to them as she can but this leaves little to live off. The city is a daunting place and it is normal for girls like Rotha to share their digs with 5 others – a room in a block of several, each with enough space for the women to sleep parallel and a stove to cook on. The bed is an elevated wooden platform with their belongings stored underneath, where cat-sized rats roam at night. They have pink mosquito nets and walls covered with magazine pages showing Khmer women in glamorous dresses. The window overlooks a swamp filled with rubbish.

The Bangladesh factory collapse last year has brought to our attention again the need for better factory conditions for garment workers in developing countries, but we also need to push for a living wage for women like Rotha too. Earlier this year four people were killed during a strike by garment workers demanding higher pay – $160 a month which is still nearly half what the Clean Clothes Campaign calls a living wage.

These workers may think their future lies in the hands of politicians and factory managers. But it is ultimately us, the consumers, who have the greatest power to influence their lives. As the Clean Clothes Campaign’s Tailored Wage report puts it, ‘Survival of the cheapest” has become the leading maxim, both in production countries as well as consumer markets’. If we keep buying cheap clothes and accessories without questioning their source, nothing will change.

In Burkina Faso, Ramata does all her leather weaving work at home, far from the city. There are no machines or factories here: she sits outside on a grass mat under a straw shelter. Her village is in the north, where children, chickens and goats run freely all day. The income she gets from her work enables her to stay in the village, and save a little too. Like her Fulani ancestors, she doesn’t have a bank account but invests her savings in the silver jewellery she wears which she will sell when she needs or wants to reinvest the money elsewhere. The Sahel is an unpredictable place to live and you never know if it will be a good or bad year for crops. Leather weaving is a family tradition that is proving lucrative again for this village. They cannot compete with the quantity of factory made products, but theirs is a unique craft which cannot be replicated easily and their allegiance to this ancient tradition is paying off.

Thanks to the growth of the internet over the last decade, it’s now easier than ever to buy and sell hand-made products from around the world or to at least look up the ethical credentials of the high street shops we’re buying from. We don’t need to travel to Asia or Africa to get the picture. And whenever we make a purchase, we are condoning the behaviour of the retailer, for better or for worse. It is time we started genuinelly caring about the source as much as the style of our clothes. It is time to change our perspective and see fashion in a new way – from the inside out.

BIOGRAPHY

Charlie Davies was formerly Fashion Editor for The Sunday Telegraph Magazine. She founded Precious Girl Magazine, a publication for the garment workers of Cambodia in 2004, and now serves traditional artisans in Burkina Faso with SAHEL Design (www.saheldesign.com). Charlie is the Fashion Revolution Day country co-ordinator for Burkina Faso.