Challenges facing the farmers who grow our cotton

Cotton makes up approximately 26% of all fibre used in the fashion and textiles industry, and cotton crops take up about 2.5% of all arable land on Earth. What’s more, cotton represents the main source of income for up to 1 billion people, of which 100 million are farmers. With this in mind, we know that cotton is at the core of fashion’s social and environmental footprint.

Unfortunately, conversations about sustainable fashion often focus primarily on the ‘cotton vs. polyester’ or ‘organic cotton vs. conventional cotton’ debate, and less so on the farmers themselves. It is imperative that we add the socio-economic sustainability issues to the environmental sustainability dialogue, which seems to dominate the discourse, and approach sustainability more holistically.

Like with most agricultural products, market dynamics are undergoing a huge shift, impacting farmers, their livelihoods, and the land they live and work on.

The global cotton supply chain

In the complex journey from seed to shop floor, cotton goes through several stages. Cotton must be grown, harvested, processed, and spun into a yarn that is ready to be woven or knitted into a fabric, before being transformed into a finished product.

64% of all cotton fibre produced around the world is used in apparel, with the remainder mostly used in home furnishings. In addition to the soft white fibre of the plant, the cotton seeds are also harvested for animal feed, cooking oil and industrial applications.

Zooming in on the agricultural stage of this global supply chain, the majority of cotton is grown in the US, China, India and Pakistan, in addition to other countries such as Uzbekistan, Turkey, Israel, Argentina and Australia.

India alone produces 25% of the world’s cotton, sustaining the livelihoods of 5.8 million farmers, the majority of whom are small-scale farmers cultivating land less than 2 hectares in size. In India’s textile industry, nearly 60% of all raw materials are made up of cotton. The textile industry also makes up about 7% of the industrial output and contributes about 12% to the country’s export earnings.

It’s worth noting the long historical journey of cotton too. Cotton is an ancient fibre that can be traced back as early as 5000-6000 BC in early civilisations of India, South America and North Africa.

Cotton trade played a significant part in the British Empire, with the East India Company importing cotton fabrics from India into Britain and across Europe. In the 18th and 19th centuries, cotton also drove the expansion of the slave trade in the US, with cotton plantation owners accumulating extreme wealth by exploiting enslaved people. During the Industrial Revolution, the cotton gin (a machine used for separating cotton fibre) was invented, and Britain quickly became the world’s biggest producer of cotton textiles. (Source)

In short, cotton’s history is tightly wound with the history of capitalism, colonialism, exploitation and industrialisation that continues to drive the fashion industry today. For more information, read Empire of Cotton: A New History of Global Capitalism by Sven Beckert.

Problems facing cotton farmers

Cotton is associated with a range of environmental issues. For example, conventional cotton (aka. non-organic cotton) uses a large proportion of the world’s insecticides and pesticides.

However, the farmers themselves also face significant social and economic challenges that the fashion and textile industry as a whole must be held accountable for, including:

- Forced labour, for example in China, where hundreds of thousands of Uighur Muslims and other ethnic minorities have been forced into unpaid manual labour in the Xinjiang cotton sector. Additionally, in Uzbekistan, both adults and children are forced by the state to pick cotton, a regime that has only recently been regulated to eliminate forced and child labour.

- Dangerous health problems are associated with chemical pesticides used in cotton agriculture. Farmers that are exposed to pesticides at work can experience acute toxicity, which causes respiratory problems, skin and eye irritation, seizures and even death. In the long-term, low dose pesticide exposure has been linked to Parkinson’s disease, asthma, mental illness and certain cancers.

- Financial hardship caused by corporate control over cotton trade and debt accrued from investing in high-cost fertilisers, pesticides, mechanised equipment and genetically modified seeds. This is largely due to insufficient access to institutional credit, leading to farmers taking on debt to pay for high input costs typically associated with GM seed cultivation with interest rates reaching up to 120% per year. Higher risks due to the impacts of climate change are further increasing the economic burden and uncertainty for the farmers. This is widely reported to contribute to India’s farmer suicide epidemic, in addition to rapidly changing weather patterns that leave crops destroyed and farmers uncompensated.

Overall, a lack of transparency and even total indifference from fashion brands on how they source cotton, in addition to under-developed support frameworks for farmers to deal with risks and market failures has allowed these problems to persist.

“Cotton farmers in India, particularly those who grow cotton in the rainfed regions, face extremely high risks due to the growing uncertainties caused by climate change,” says Abhishek Jani, CEO of Fairtrade India. “This risk is heightened for them when the rising inputs costs of conventional and GM cotton cultivation is considered along with the fact that most of their credit needs for buying inputs are met through private money lenders who charge anywhere between 24% to 120% of annualised interest rates. This high indebtedness along with the high risks in cultivation is a recipe for economic disaster.”

The impact of Covid-19 and corporate control

Cotton as a commodity is under tight corporate control, with powerful multinational corporations maximising profit by exploiting vulnerabilities in cotton agriculture and the people that rely upon it. Cotton prices are skyrocketing in the global market, but farmers reap no benefits from this surge, instead, they are being pushed to produce more under high risk conditions.

“Once the crop is harvested, the farmers are unable to hold onto their harvest and almost immediately have to sell – if the crops are not already pledged- to pay off their debts. This situation further makes them vulnerable to market exploitation and in many cases it is others who are able to profit more even when the market price of cotton yarn or lint skyrockets,” says Abhishek.

The global Covid-19 pandemic has also impacted cotton farmers over the past 12 months. For example, migrant farmworkers were left stranded and without support when the virus spread through India. The country’s widespread lockdowns in 2020 caused massive disruptions in the cotton supply chain (Source).

“Covid-19 not only increased the risks for the farming communities as they were left with the unenviable choice of either staying locked down to protect their health or harvesting and planting crops which would otherwise get damaged or destroyed but the pandemic also increased uncertainty for the cotton farmers with news of the order cancellation by brands and reduced retail activity creating confusion about the market situation,” Abhishek confirms. “Furthermore, many of the farmers also migrate to cities to offer seasonal labour and were stuck on the wrong side of the lockdown in dire conditions. With newer more virulent strains of virus emerging in India the risk for the farming community is far from over.”

How to support cotton farmers

According to Cotton Diaries, a collective working to transform the cotton supply chain, if fashion brands want to ensure the cotton they are sourcing does not exploit people and the planet, they need to pay meaningful due diligence to their suppliers and invest in full transparency that traces cotton back to the original farm, identifying every broker, mill, ginner, spinner, and manufacturer involved along the way.

“We need brands to make honest commitments to overall social, economic and environmental sustainability from seed to stitch; instead of the corporate greenwashing we see in most advertisements, stores and pamphlets today. It is only then that fashion can begin to make a positive impact on the farming communities, we hope that this change in values will be driven by conscious consumers urging brands to be more accountable,” says Devina Singh, Communications Manager of Fairtrade India.

As consumers, we have the power to demand better. The brands who we invest in should be investing in more sustainable cotton sourcing options that support farmer livelihoods, such as organic, Fairtrade and regenerative agriculture. Furthermore, it is also important that consumers ask brands about the tangible impact on both the environment and farmer and worker livelihoods from their sustainable sourcing commitments, demanding evidence of the change which is being claimed.

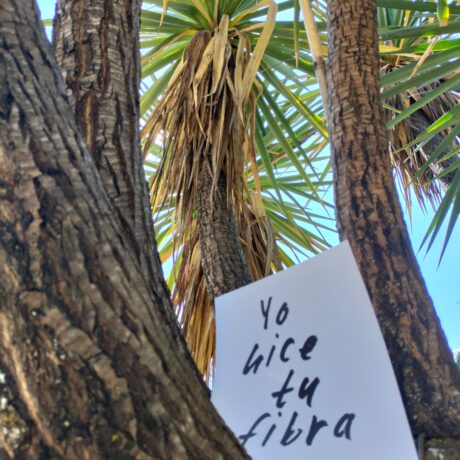

“We always encourage our supporters to ask the right questions. We want brands in India to demonstrate transparency and to show us the people who make our clothes. We continue to raise awareness about #WhatsInMyClothes and #WhoMadeMyClothes as we need to be mindful of how our fashion choices impact farming communities,” says Suki Dusanj-Lenz, Country Coordinator of Fashion Revolution India.

“As we campaign for a global shift towards sustainable fashion we are acutely aware of the value of India’s traditional fibres and textiles which is even more reason to ask #WhoMadeMyFabric to evolve our #WhoMadeMyClothes campaign,” agrees Aliya Curmally, Co-founder & Head of Strategy Fashion Revolution India.

To hold brands accountable for their cotton sourcing practices, ask #WhoMadeMyClothes and #WhoMadeMyFabric on social media or email a brand directly. Find out more about how to make a difference here.

Further reading

Cotton Diaries: Pushing for Change

Life on the Margins during the Covid-19 Outbreak