Fashion consumption: Unfit, Unfair, and Unfashionable

This is a guest blog post by Katia Dayan Vladimirova, Researcher at the University of Geneva and Founder of the international research network on Sustainable Fashion Consumption.

As a researcher, I have been working on the nexus between fashion consumption and sustainability since 2017. I was always curious as to why we buy so many clothes and what insatiable need drives wanton overconsumption of cheap stuff. My research quest was inspired by a personal journey: Living in London, Rome, and New York in my twenties, I got accustomed to buying clothes frequently and mostly on sale. Repeated impulse purchases left me with a cluttered closet, unmatching garments – and a hole in my wallet at the end of the month. My fashion shopping story is a typical one when it comes to Millennial women in the Global North. We also, according to the Eurostat, have much stronger pro-environmental attitudes than the older generations.

With new data on the fashion industry’s impacts coming to light, affluent fashion consumers in Europe, North America, Australia and other wealthy countries started to question how to reverse the tide. Vivienne Westwood suggested to Buy Less, Choose Well, Make It Last – a fine motto to move away from the unsustainable fast fashion trends. People are experimenting with living with fewer clothes – and minimalist fashion challenges such as Project 333 or the 10×10 challenge prove that having less stuff actually has amazing positive impacts on people’s creativity and well-being.

But the impacts of these changes on the large scale were never clear. Would it matter if 1% or 50% of affluent consumers adopted minimalist wardrobes? What would it mean in terms of carbon emissions’ reductions? Can we ask everyone to abandon fast fashion or would that be unfair to those who cannot afford more expensive garments? Whose consumption patterns are actually the most wasteful and who should change their ways more urgently? And my favourite: with the growing population, would having enough clothes (per capita) mean that we’d breach planetary boundaries?

All of these questions – and more – were answered by a new report by Hot or Cool Institute, co-authored by several members of the International research network on Sustainable Fashion Consumption. The analysis offers insights into inequalities in fashion consumption – among and within G20 countries – and proposes a “fair consumption space” for fashion. As a researcher and world-class nerd, I am very excited to finally have these numbers. Because they tell us exactly which groups of consumers buy too much and who does not have enough. They also tell us how many clothes per person would be “enough” – both in terms of planetary boundaries and minimum levels for a decent life.

Key findings

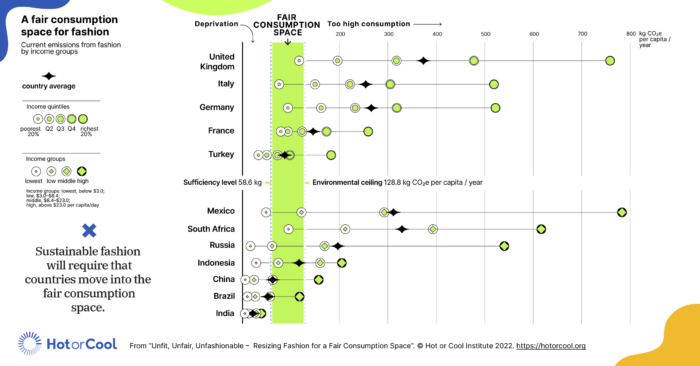

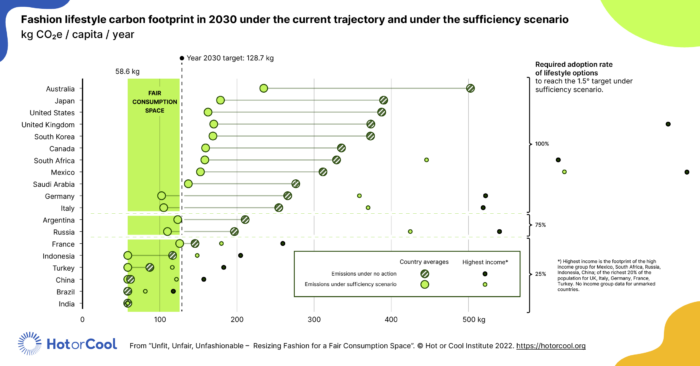

The report shows that fashion consumption patterns are structurally unfair: there are massive inequalities between and among the G20 countries considered in the analysis. Check out the graph below. While the richest 20% in the UK emit 83% above the 1.5-target, 74% of people in Indonesia live below sufficiency consumption levels of fashion. Fashion footprints need to be reduced by 60% on average by 2030 among G20 high-income countries (Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, the UK, and the US). Upper-middle-income countries (Argentina, Brazil, China, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, and Turkey) must reduce their footprints by over 40% by 2030. While these countries are, on average, overshooting the environmental ceiling, a significant share of their population remains below sufficiency. In lower-middle-income countries (India and Indonesia), the average carbon footprint of fashion consumption is below the 1.5-degree limit.

On the other hand, there are some shocking inequalities within countries, as well. A representative sampling of G20 countries shows that the lowest income quintile is responsible for 6%-11% of the national carbon footprint, the second quintile for 10%-13%, the third quintile for about 17%, the fourth quintile for 24%-26%, and the highest income quintile for 36%-42%.

The richest 20% need to reduce their footprint of fashion consumption by 83% in the UK, 75% in Italy and Germany, and 50% in France.

Average carbon footprints from fashion consumption among 14 of the G20 countries exceed the limit of emissions set by the 1.5-degree aspirational target of the Paris Agreement. On average, the fashion consumption of the richest 20% causes 20 times higher emissions than that of the poorest 20%. This ratio varies substantially across countries, following levels of income inequality.

Solutions?

The Hot or Cool report calls for “resizing” fashion by focusing on three key elements. First, it is important to acknowledge that it is the consumption of the richest 20% that is most problematic. Interventions at the national and international levels would fail if they do not affect consumption by the richest 20%, who, besides their direct impacts, also influence the aspirations of others. Data shows that many of the less affluent groups, also in wealthy countries, consume within or close to the limits of the fair consumption space. An equity-based approach to allocating per-person carbon budgets for the 1.5-target of the Paris Agreement implies greater reductions in carbon emissions from individuals with a higher carbon footprint.

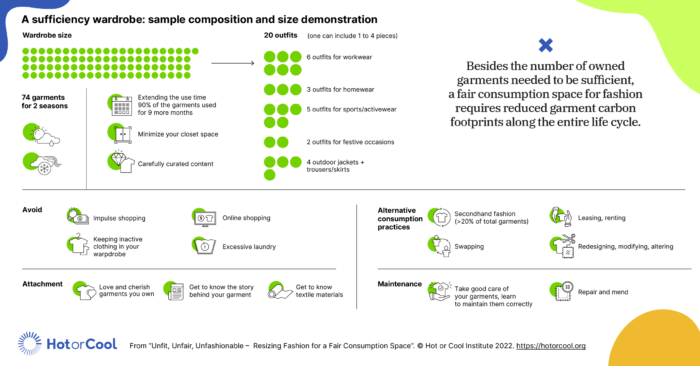

Second, the report shows that the most effective way to reduce the carbon footprint of our inflated wardrobes is to… simply buy less. Reducing purchases of new clothes will lead to reductions over 4 times higher than the next best solution (keeping garments longer) and over 3 times higher than what is considered achievable through accelerated decarbonization of the fashion industry. The report even suggests a sufficiency wardrobe size, which seems to me pretty generous actually – taking into account different needs and climates. After all, this was the size of wardrobes several decades ago, and people survived:)

Finally, the report is categorical about the need for systemic change. To meet the 1.5-degree target, a system-level change is needed in fashion production and consumption, implying both efficiency improvements in the fashion industry and changes in lifestyles and consumption behaviour. Neither of these approaches alone can bring about the required reductions in carbon footprint.

Key takeaways

Can we live with minimalist wardrobes that comply with sufficiency principles? Shall we experiment? I would like to use this post as an opportunity to call for creative experimentation within a fair consumption space for fashion. If other minimalist fashion challenges are any indication, it will only increase our wellbeing, while reducing the pressure on the planet. Tag your experience as #1point5wardrobe and let’s see all the different creative opportunities that arise!