Famine by Fashion

With large proportions of the world taking part in a global lockdown, we are being made to adapt to a new normal. For many of us this means working from home, a life lived in lounge wear and only leaving the house when absolutely necessary.

The impact of this ‘new normal’ on the supply chain that provides our lounge wear is, however, something completely different. You may have seen some news coverage of this drastic shift, but it will likely have focused on the formal employment sector for textile workers, overlooking the vast numbers of workers who have little to no contract at all, the informal sector.

In this article, I will illustrate the impact of this virus, starting from the end of December when the outbreak was first announced until the end of April (the time of writing). My aim is not to insist on solutions, but to draw a clear picture of the people who stitch the clothes you wear, who are, by far, the most vulnerable part of the whole supply chain; with a view to following up with a more deep and meaningful conversation with sustainable fashion advocates.

To provide some context here, I am the CEO and Founder of Project Work Force, with over a decade of experience in the fashion industry. Our mission is to ensure safe workspaces for garment workers within the informal sector, based in Dhaka, Bangladesh. We supply clothes to retailers across Europe and America, emphasising the need for ethical structures in the garment industry.

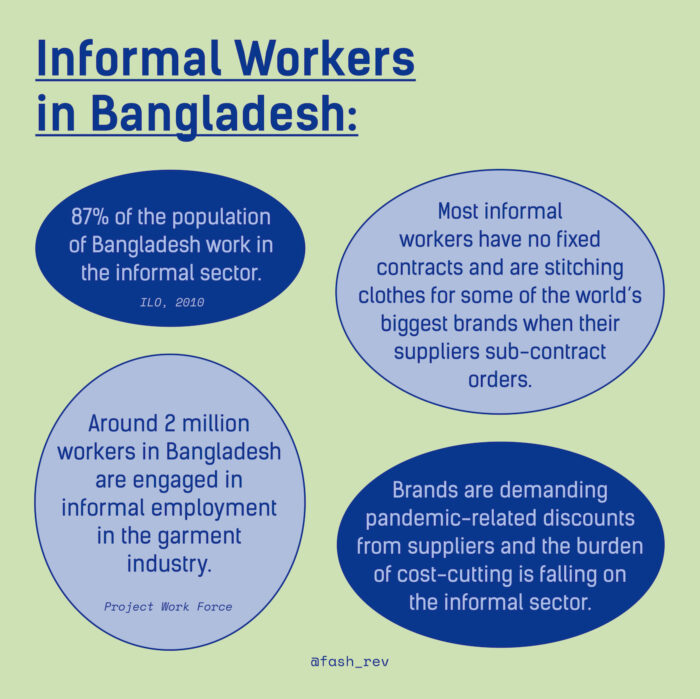

According to our research, there are over two million workers in the Bangladeshi garment industry working in the informal sector; the majority of them stitching workers with no fixed contracts, employed by factories that take sub-contracts from export manufacturers. These are the factories supplying to well-known brands with garments when their direct vendors are unable to fulfil their orders, typically because order volumes are bigger than their capacity, or smaller than their minimum order. In some cases, they are simply looking for cheaper alternatives.

When the first COVID-19 alarms sounded in late December, the impact on the fashion industry was quietly starting. Without clear indications of the consequences of COVID-19 spreading, we sent a team including our Head of Business, Head Designer and Head of Merchandising on a trip to China in January in order to seek out fabrics for Spring/Summer’21. When they returned what they had to say was frightening. China was surprisingly empty and there was restricted entry into Hong Kong. But we put some of that down to the start of Chinese New Year and carried on with our work.

At the end of January when we started booking in our initial orders for Winter ‘20, we received news that our Chinese suppliers were remaining closed for an additional two weeks after Chinese New Year. This prompted a very quick response, shifting fabric production from China to Turkey and India, since there were clear concerns about how reliable suppliers in China would be going forward.

In February, we had booked a record number of orders for immediate deliveries for Spring/ Summer 2020 and Autumn/ Winter 2020. The assumption was that this novel virus would impact China only and we remained in contact with our mills, there was still little indication of the wider impact to come. Orders kept coming in and we adapted.

Then the situation began to escalate. By mid-March we were told by our buyers in Italy, Canada and the US to put all shipments on hold. The same orders that needed to be rushed through one month previously, now completely stalled. This was communicated with generic emails stating that goods that were ready to ship would not be collected and winter 2020 orders would likely be cancelled. A few days later 80% of our Autumn/ Winter 2020 orders were cancelled, even though these were now in production in factories, with payments already made and production already in progress.

With it becoming clear that payment and collection of these finished goods was not going to be forthcoming, it was announced in Bangladesh that over 1 million garment workers, in the formal sector, would not receive their salary. The government quickly stepped in and announced a loan funding plan so that factories would keep their workers on salary.

On 25th March we called 64 factories in our network who employ over 15,000 workers to find out their contingency plans. The plan, we were told, was to layoff 100% of their workforce by the end of March. Most of the factory owners turned their phones off, they had no alternative.

What this has done to garment workers, who live hand to mouth, has been staggering. These workers cannot work from home. With no government funded income, the prospect of zero wages poses a greater risk than that of COVID-19. Thousands of skilled labourers are willing to work regardless of the risk, to ensure they’re able to pay for food and rent for their families. Independent organisations have attempted to combat this crisis with mass rice deliveries.

By the end of March, all governments in Europe and the United States had declared large scale stimulus packages and interest free loans for businesses to support their domestic industries. Some retailers and brands that we work with had pounced on this opportunity and reopened their discussion to restart production for winter goods.

However, these new orders were proposed with a condition – prices need to be 20-30% lower than previously agreed. According to the brands, as the global market has much greater supply than demand, prices needed to be cut. Not only that, they had requested that their delivery dates must be met, otherwise the suppliers face the risk of airfreight costs or cancellation.

We had rejected the lower prices and delivery dates and I was threatened with having all future contracts cancelled once the lockdowns are relaxed and business reopens. See, in the world of fashion, the retailer and brands wields all the power as supply far outstretches demand and the products can be easily replicated.

How can a supplier confirm these reduced prices and stringent delivery dates when you do not know how many working days you have between now and your delivery dates?

Well, you go to the informal sector and get them to do it.

At the time of writing this article, Bangladesh has officially extended the lockdown till 16th Mayand further extensions are highly likely. However, these rules don’t really apply to the informal sector.

Due to the extreme price pressures from buyers after the markets reopen, most export factories will not be able to accept such low prices because they have high fixed costs. However, wages in the informal sector are simply determined by demand and supply, market mechanisms with no regard for working conditions. Workers within the informal sector will take large pay-cuts because they are desperate and need to feed themselves, allowing suppliers to meet the lower prices set by the buyers.

If the situation continues and more factories in the formal sector go bankrupt, then more workers will be forced to move to the informal sector, being paid well below minimum wage to fulfil richer countries’ thirst for cheap clothes.

No one knows the exact timeframe on this. We predict this shut down might mean no income for these workers until October. There is no financial aid being offered from the government to the informal sector and no support from the buyers that have depended on these workers for decades. We are facing a very severe food shortage. But the term food shortage is inappropriate, there is no shortage of food, the reality is there is plenty of food to go around, however these individuals will have no purchasing power to access any food. It costs on average 30 pence (38 cents) a day to feed one person in Bangladesh, with £5 being enough to last one person 2 weeks. In these uncertain times, one thing that is certain is this is a problem that should be and could be prevented.

You can find out more about Project Work Force and how they are working to support garment producers through the current crisis here.