Consumption in the Digital Age

Bronwyn Seier is Fashion Revolution’s content coordinator. As we focus on the theme of consumption for the month of November, she shares her MA thesis on the link between Instagram use and hyper-consumption.

***

It’s been estimated that the average millennial will spend just over 5 years of their life browsing social media. In contrast, I spent just over a year and a bit researching the implications of Instagram on consumer culture and human behaviour.

It all began when I was researching an £8 t-shirt from a UK fast-fashion brand as part of a group project for university. Having only just arrived in the UK from Canada, and being pretty far from the brand’s target customer (by nature of doing an MA on fashion sustainability), I was completely unfamiliar with the brand. Diving into their Instagram feed, I found the communication around exponential consumption, even at the degradation of bank accounts and financial priorities, severely horrifying.

Months later, when Mary Creagh, chair of the UK parliament’s Environmental Audit Committee, wrote to ten major high street brands asking for testimony on how the retailers are working to mitigate their environmental impact, the same brand’s CEO all but ignored her letter. The 35 year-old self-proclaimed “rapid fashion” entrepreneur sent a proxy to the parliamentary hearing, suggesting the his dismissal of environmental concerns. While this brand’s consumption coercion is pretty far from subtle, I soon began to see the subliminal cues of almost every brand, influencer, and pastel coloured motivational quote on my explore page.

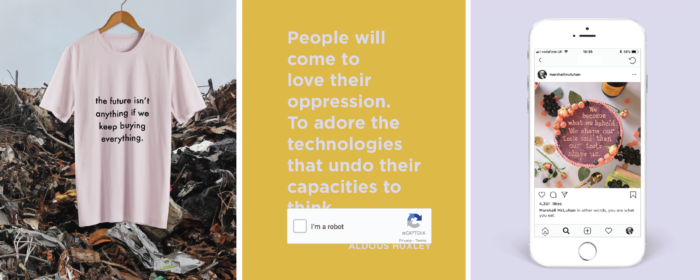

The problem is not isolated to singular brands, price points, or manufacturing countries. Overconsumption is a global problem that warrants immediate and devoted action. And with digital media continually encouraging us to buy more, wear our things for less time, and discard them thoughtlessly, the under-researched phenomenon of influencer culture sparked my curiosity. While I can’t collate my dissertation-length findings into a digestible amount of words, here’s a taste of what I learned and why it matters…

Instagram widens our lens for social comparison

The thing about technology is that we’re never really aware of its impact upon invention. This is as true for the sewing needle as it is for the iPhone. Cultures invent technologies that go on to shape the behaviours and mindsets of subsequent cultures. And then, in our own implicated existences, having absorbed the innovation to come before us, we invent and shape the next generation by how we create and use technology. Instagram is no different. It reflects this intrinsic call to self-expression that has always existed. But self-expression for what? If Instagram is literally a mechanism to overshare, then why we do it is something else entirely.

Instagram is to identity what Uber Eats is to takeaway. Before it, our social comparison was limited to a single menu: the people that we knew, who were immediately accessible to envy. But now, Instagram offers us unlimited images of bodies, lifestyles, social classes, fashion aesthetics, and geographies from which we can ogle and emulate. The options have been widened by a factor of follower counts.

In 1954, Leon Festinger introduced the concept of social comparison. He said that humans use downward social comparison, judging those they perceive to be lesser (of looks, status, income, intelligence, etc.), to affirm their sense of self. Likewise, we use upward social comparison (to celebrities and influencers) to frame our aspirational selves. In this offering of a catalogue of aspirational usernames lies Instagram’s biggest draw: the escape of quiet, arms-length jealousy fuelled by a simmering hope that, “I could be her”. And of course, where there’s longing, desire, and self-hatred there’s money to be made, particularly in beauty and fashion.

We compare, and improve, by way of consumption

Self-expression rarely takes place without consumption. It was Edward Bernays, godfather of the term ‘public relations’, who uncovered the idea that by linking products to our feelings and desires, rather than our intellect or rational needs, we could turn emotion into capitalism.

Before Bernays, Thorstein Veblen, and his Theory of the Leisure Class, introduced this idea of conspicuous consumption as a sort of human-peacocking. While it was clear that aristocrats of the time had an affinity for luxurious goods, it had yet to be uncovered that these things were actually symbols of power and status. Further, Veblen said that the consumption of upper class groups influenced the desires of those less privileged. Today, we call this idea trickle down fashion, a fancy way of explaining why so many women in the 80s got married in knockoffs of Princess Diana’s wedding dress.

Fashion is the interface between who we are, and how we want people to perceive us. Charles Horton Cooley famously said, “I am not what I think I am, I am not what you think I am, I am what I think you think I am”. That’s the principle behind his Theory of The Looking Glass Self, but whenever I read it, I’m reminded of that Friends episode where Joey, Rachel and Phoebe realise Chandler and Monica are hooking up, and everyone is all, “Do they know that we know that they know?”

Effectively, new clothing is like that magic mirror in the first Harry Potter book. It shows us a reflection of ourselves in which our utmost desires have taken shape. We put on these shiny new garments and see ourselves as worthy, confident, and powerful. And these garments, worthless on a hanger, breathe confidence, personality, and self-worth into the subconscious mind of the wearer.

So what can we do?

GET OFFLINE: Researchers have found that people who spend more time on Instagram tend to show higher rates of hedonic consumption, meaning that these users consume greater amounts of non-essential goods. The answer might be as simple as: less social media = less accumulation of needless stuff.

DON’T BLEND IN: The bar for difference has been lowered through digital communication. As humans, we juggle this innate call to be seen as unique and special while simultaneously trying to fit in and seek belonging. It’s the tension between these two polar goals that keeps things interesting. The call to be different is often a generator of art, philosophy, and creativity, while the call to belonging is what keeps most people from social deviance, like farting in public or chewing with their mouths open. But that same call to belonging also has so many of us rejecting actual fashion and uniqueness for mere uniform. It’s the reason that a white polka dot dress from Zara was so widely purchased that it earned itself a dedicated Instagram account.

TAKE A STAND: In the age of the Internet, very few things in life are certain. Yet, I am sure that fashion, in all its eccentricities is here to stay. I also know that communicating identity in visual and visceral ways is core to what makes us human. I do not believe that facing the knowledge of overconsumption, the realities of Influencer culture, or our personal contributions to inequality can make shiny new things seem less desirable. But, in the face of non-idyllic circumstances, we all get to decide whether to put our head in the sand and follow blindly, or open our eyes and see the grit of our actions and the consequences of our consumption.