Hungarian:

A tudatos fogyasztók új hullámával a fenntartható divat iránti kereslet virágzik és ha már erre az oldalra tévedtél, akkor biztos van bennünk valami közös. Lehet te is szenvedélyesen szereted a divat világát, vagy lelkesen próbálsz megragadni minden olyan alkalmat, amivel a saját mikrokörnyezetedben is olyan változást tudsz elérni, amivel egy picit könnyíthetsz a bolygó terhén.

A Fashion Revolution mozgalom tagjaként hiszünk a közösség erejében, egyéni szinten is lehet változást eredményezni!

Egy tanulmány szerint az Egyesült Államokban a vásárlók 59%-a szeretné, ha a divatipar fenntarthatóbbá és környezetbarátabbá válna. Bármely divatháznak, amely az élvonalban szeretne maradni, annak kapcsolódnia kell ehhez az irányvonalhoz, és meg kell felelnie avásárlók igényeinek. Ma már nem lehet szemet hunyni a textilipar által okozott környezetkárosodás felett. Mind a fogyasztók, mind az iparág egészében bekövetkezett változás miatt a fenntartható divatpiac értéke 2021 és 2025 között várhatóan több mint 3 milliárd dollárra nő.

A jó hír az, hogy rengeteg olyan lépés van, amivel a fenntartható divat ösvényén olyan játszi könnyedséggel lépdelhetsz, mint Carrie Bradshaw az Upper East Side utcáin. Ez a lista útravalónak szolgálhat, miközben tudatosabb vásárlási szokásokat alakíthatsz ki.

Secondhand

Turkálóba, vintage üzletekbe vagy gardróbvásárra járni, olyan, mint egy kincskeresés, sosem tudhatod mi akad majd a kezedbe. Az adott darab történetet mondd el szavak nélkül. A használt ruha piac egyre nagyobb teret hódít, de nem is csoda, hiszen ezek a darabok karaktert és egyediséget adnak a gardróbunkhoz, miközben új életet adunk a mások által már megunt ruhadaraboknak.

Upcycling

Az upcycling, más néven értéknövelő újrahasznosítás, az ökotudatos fogyasztók kreatív oldalát hozza elő. Izgalmas alkotói folyamat, amikor az eldobott rongyokból valami teljesen új születik, farmerből táska vagy régi nyakkendőkből szoknya. Rengeteg lehetőség rejlik ebben a technikában, így érdemes szabadjára engedni a fantáziánkat.

Körforgásos divat

2025-ben is az egyik legdominánsabb trendek közé tartozik a körforgásos divat. Ez egy olyan üzleti modell, amely a hulladék csökkentésére, valamint az erőforrások újrafelhasználására és újrahasznosítására összpontosít. A cél az, hogy már a tervezés folyamat során gondoljunk arra, hogy mi lesz a ruhák sorsa életciklusuk végén, miként lehet őket majd újrahasznosítani. Izgalmas innováció zajlik a textiliparban a biológiailag lebomló vagy komposztálható szálak előállítása terén. Az egyik ilyen újítás a CELYS komposztálható szál, amely 179 nap alatt természetes módon szén-dioxiddá, vízzé és biomasszává bomlik le. Már a boltok polcain is találkozhatsz olyan termékekkel, amelyek 100% újrahasznosított anyagból készülnek, vásárlás előtt minden esetben érdemes elolvasni a ruhák címkéjét.

Etikusság és átláthatóság

Az etikus beszerzés azt jelenti, hogy az anyagok beszerzése során nem okoztak kárt sem az embereknek, sem a bolygónak, valamint a gazdálkodás, a termelés és a forgalmazás során érvényesítették a tisztességes kereskedelmi gyakorlatokat. 2025-ben a márkáknak átláthatóbbnak kell lenniük gyakorlatukkal kapcsolatban, és fenntartható állításaikat tanúsítványok vagy harmadik fél által végzett ellenőrzések formájában kell alátámasztaniuk.

Minimalista divat

A fenntartható divatmárkák egyre inkább a minimalista esztétikát alkalmazzák, hogy felszámolják a gyakori szezonális vásárlások szükségességét. Ez az irányzat legkönyebben az egyik kedvenc mondásunkkal írható le; „a kevesebb több”. A trend fő jellemzői a letisztult vonalak, semleges színek és időtlen dizájnok. A hangsúly a minőségen van, nem pedig a mennyiségen. Sok esetben bele sem gondolunk, hogy egy-egy darabot többféleképpen is fel tudunk venni, csak a megfelelő párosításra van szükség. Az eszközeink tárháza végtelen, csak a képzelet szabhat határt.

Remélem sikerült ráébreszteni arra, hogy a fenntartató divat, nem is olyan idegen és unalmas terep, mint ahogy azt elsőre gondolná az ember. Válaszd ki számodra a legjárhatóbb utat és alkalmazz Te is zöldebb gyakorlatokat!

Írta: Arnóth Nikolett, Fashion Revolution Hungary

Forrás: https://www.celys.com.au/blog/sustainable-fashion-trends-for-2025-what-to-expect

Képek forrása: https://www.pexels.com/hu-hu/

English:

With a new wave of conscious consumers, the demand for sustainable fashion is booming, and if you’ve landed on this page, then we have something in common. You may be passionate about fashion, or you may be eager to seize every opportunity to make a difference in your own micro-environment and help the planet.

As a member of the Fashion Revolution movement, we believe in the power of community, and we can make a difference on an individual level!

According to a study, 59% of consumers in the United States want the fashion industry to become more sustainable and environmentally friendly. Any fashion house that wants to stay ahead of the curve must connect with this trend and meet the needs of its shoppers. Today, we can no longer turn a blind eye to the environmental damage caused by the textile industry. Due to the shift in both consumers and the industry as a whole, the sustainable fashion market is expected to grow to over $3 billion between 2021 and 2025.

The good news is that there are plenty of steps you can take to make your sustainable fashion journey as effortless as Carrie Bradshaw on the streets of the Upper East Side. This list can serve as a guide while you develop more conscious shopping habits.

Secondhand

Going to thrift stores, vintage stores, or closet sales is like a treasure hunt, you never know what you’ll find. Tell the story of a piece without words. The secondhand clothing market is gaining ground, and it’s no wonder, as these pieces add character and uniqueness to our wardrobes while giving new life to clothes that others have already gotten tired of.

Upcycling

Upcycling, also known as value-added recycling, brings out the creative side of eco-conscious consumers. It is an exciting creative process when something completely new is created from discarded rags, from jeans to bags or from old ties to skirts. There are many possibilities in this technique, so it is worth letting your imagination run wild.

Circular fashion

One of the most dominant trends in 2025 is circular fashion. It is a business model that focuses on reducing waste and reusing and recycling resources. The goal is to think about what will happen to clothes at the end of their life cycle and how they can be recycled during the design process. Exciting innovation is taking place in the textile industry in the field of producing biodegradable or compostable fibers. One such innovation is the CELYS compostable fiber, which naturally breaks down into carbon dioxide, water and biomass in 179 days. You can already find products on store shelves that are made from 100% recycled materials, so it’s always a good idea to read the label before buying.

Ethics and transparency

Ethical sourcing means that materials have been sourced without harming people or the planet, and fair trade practices have been applied in farming, production and distribution. In 2025, brands will need to be more transparent about their practices and support their sustainability claims with certifications or third-party audits.

Minimalist fashion

Sustainable fashion brands are increasingly adopting a minimalist aesthetic to eliminate the need for frequent seasonal purchases. This trend is best described by one of our favorite sayings; “less is more”. The main characteristics of the trend are clean lines, neutral colors and timeless designs. The emphasis is on quality, not quantity. In many cases, we don’t even think that we can wear a piece in multiple ways, all we need is the right pairing. Our arsenal of tools is endless, only our imagination can set the limit.

I hope I managed to make you realize that sustainable fashion is not as foreign and boring as you might think at first. Choose the most viable path for you and adopt greener practices!

Written by: Arnóth Nikolett, Fashion Revolution Hungary

Isabela State University in Ilagan City is at the forefront of a textile revolution! The Philippine Textile Research Institute (PTRI) has set up a facility there to create yarn and thread from bamboo – a sustainable and versatile material.

This isn’t just about replacing cotton with bamboo. PTRI is blending bamboo with cotton to create unique yarns perfect for clothing. Imagine – government uniforms made with Philippine-developed, eco-friendly bamboo fabric!

Ilagan City’s commitment to sustainability aligns perfectly with PTRI’s vision. The yarn production process is automated, minimizing waste. Plus, they cleverly recycle scraps into new threads! This innovative facility produces 50kgs of yarn every 8 hours, paving the way for a greener textile industry.

The future of textiles is being woven right here in Ilagan City, and it’s made from bamboo!

This post is a translation of a recent Guardian article exploring textile waste, written by journalist Tamsin Blanchard.

A tavalyi évben hatalmas mértékben növekedett a hipergyors divat, amely jelentős szénlábnyommal és hulladéktermeléssel jár. Mérgező mennyiségű poliészter ruha került legyártásra, illetve a szemétbe és ne feledjük, hogy mennyire szoros kapcsolat van a fosszilis tüzelőanyagok és a ruháinkban lévő szintetikus anyagok között.

“A fosszilis divat a fast fashion számos súlyos problémájának a középpontjában áll: olcsó anyagok, túlzott függőség a szintetikus anyagoktól, hulladékválság és az egyre növekvő kibocsátás” – állította a Fossil Fuel Fashion, egy új szervezet, amely a New York-i Klímahéten indult szeptemberben, és olyan szervezetek koalícióját tömöríti, amelyeknek célja a fosszilis tüzelőanyagok fokozatos kivonása az iparágból. A fosszilis tüzelőanyag-alapú poliészter olcsó, és a hipergyors divat kedvelt anyaga, amely továbbra is leuralja a piacot, annak ellenére, hogy júniusban számos kritika érte. A Shein hat divatipari influencert fizetett, hogy látogassanak el kínai gyáraikba és az influencerek ezután elragadó véleményeket osztottak meg a kulisszák mögül. A 66 milliárd dolláros divatmárka továbbra is arra ösztönöz minket, hogy olyan ruhákat vásároljunk, amelyekről nem is tudtuk, hogy szükségünk van rájuk, és amikre valójában biztosan nincs is szükségünk. A versenyfutás azonban csak most kezdődött meg. A kínai Temu nevű vásárlási alkalmazást, -amely a Sheint is megszorongatja a 99%-os kedvezményes ajánlataival-, már több mint 7 milliószor töltötték le, mióta áprilisban elindult az Egyesült Királyságban.

Nem csak rossz hírrel tudok szolgálni. A mezőgazdaság és a divat közötti kapcsolatról még soha nem esett ennyiszer szó; a “regeneratív” a tavalyi év egyik legelterjedtebb divatszava volt. Ahogy Safia Minney, a Fashion Declares alapítója elmagyarázza, a divat nem csak arról szól, hogy a gazdáknak biztosítaniuk kell a szén-dioxidot a talajban, hanem az egész folyamatról – a pamut, a kender, a len, a gyapjú és a bőr termesztésétől kezdve egészen a ruhadarabok életciklusának végéig. A regeneratív divat egyik győzelmére októberben került sor, amikor Justine Aldersey-Williams bemutatta az Egyesült Királyság első saját termesztésű, házi fonású farmerját, amely a lancashire-i Blackburnben termesztett lenből és gyapjúból készült.

2023 volt az az év is, amikor a hulladékkolonializmus szörnyű környezetszennyezése újra a figyelem középpontjába került. Februárban a ghánai Accra Kantamanto piacán működő The Or Foundation, amely a divat szemétproblémájának igazságtalanságával foglalkozik, közzétette a Stop Waste Colonialism (Állítsuk meg a hulladékgyarmatosítást) című jelentését. Ebben kifejtette, hogy “a divatipar a globális használtruha-kereskedelmet de facto hulladékkezelési stratégiaként használja“. Májusban ruházati kereskedők egy csoportja Brüsszelbe utazott, hogy megvitassák a döntéshozókkal a kiterjesztett gyártói felelősségről (EPR) szóló európai jogszabályokat. Fontos, hogy a kantamantói piacot védő szervezeti tag is részt vett ebben a beszélgetésben, mivel a világ textilhulladéka az ő küszöbükön végzi.

Jeremy Hutchison művész egy lépéssel tovább vitte a küszöbön lévő szemét gondolatát, amikor a “fogyasztás utáni imperializmus szörnyetegévé” vált, egy fulladozó, 2,5 méter magas textilzombi, a Dead White Man formájában. Az alkotás a The Or Foundationnel való együttműködésben készült, és a ghánai obroni wawu kifejezésre utalt, ami annyit tesz: halott fehér ember ruhája. A kantamantói piac kereskedői, így emlegetik a globális északról származó selejtes árukészletet. A Dead White Man októberben fellépett a brit textilbiennálén Blackburnben, majd rögtönzött látogatásokat tett pár ruházati beszállítónál, köztük a Marks & Spencernél. Az M&S egyike azoknak a márkáknak, amelyek címkéi gyakran megjelennek Accra strandjain.

Szeptemberben Clare Press, a Wardrobe Crisis podcast alapítója – amely a fenntartható divat iránt érdeklődők számára elengedhetetlen műsora – kiadta legújabb könyvét, a Wear Next-et: Fashioning the Future (A jövő divatja) című könyvét, amelyben számos ilyen problémára kínál megoldásokat. “A túltermelés és a hipersebesség a divatipar két legnagyobb problémája” – mondja. A Fashion Revolution éves Fashion Transparency Indexében arról számolt be, hogy a nagy divatmárkák 88%-a még mindig nem hozza nyilvánosságra éves termelési volumenét. Az Index szerint globálisan annyi ruha van a rendszerben, hogy a következő hat emberöltőnyi generációt fel tudnánk öltöztetni (ha a bolygó nem megy tönkre előtte).

Továbbá, tavaly kezdte el az európai jogalkotás beleásni magát a fast fashion szabályozásába. Decemberben az Európai Parlament az új “ökodizájn” keretrendszer részeként elfogadta az eladatlan ruhák, kiegészítők és lábbelik megsemmisítésének tilalmát, a ruházati cikkek pedig digitális termékútlevelet kapnak. A várhatóan 2026-ban hatályba lépő QR-kód nagyobb átláthatóságot biztosít majd a vásárlók számára az anyagokról, a gyártásról, sőt, még akár javítási tippeket is adhat. Szabályozás nélkül a márkák még mindig nem vállalnak felelősséget termékeikért, az általuk felhasznált anyagokért és ellátási láncukért. A jogalkotás végre elkezdi őket arra késztetni, hogy kollektív lépéseket tegyenek.

Azonban a ruhaipari munkások folyamatos kizsákmányolása sajnos világszerte folytatódott. 2023-ban volt 10 éve, hogy a bangladesi Dhakában található Rana Plaza gyár katasztrófája során 1134 ember vesztette életét, és legalább 2000-en megsérültek, amikor a gyár összeomlott. Most decemberben pedig több mint 50 márka csatlakozott az újonnan kiterjesztett nemzetközi megállapodáshoz, amely hozzájárult a biztonságosabb munkakörülményekhez több mint 2 millió bangladesi ruhagyári munkás számára, 48 aláírta a bangladesi biztonsági megállapodást és 88 a legutóbbi pakisztáni megállapodást.

Az átláthatóság azonban továbbra is hiányzik. Novemberben egy derbyshire-i nő egy kínai rab személyi igazolványát találta meg a Regatta kabátja ujjbélésében. Az ellátási láncokban rejtőző modern rabszolgaság még mindig jelen van a divatiparban, a szegénységi bérezés pedig még mindig az iparági normák közé tartozik. Amint arról a Clean Clothes Campaign beszámolt, idén június 25-én a bangladesi Tongiban halálra verték Shahidul Islam szakszervezeti vezetőt, aki a munkajogok védelmében tevékenykedett. Az új bangladesi minimálbér elleni folyamatos tiltakozások következtében novemberben négy munkás meghalt, és legalább 115 munkás és szakszervezeti tag került börtönbe. Maeve Galvin, a Fashion Revolution globális politikai és kampányigazgatója szerint “olyan messze vagyunk attól, hogy a munkavállalók elérjék a társadalmi igazságosságot, hogy az szégyenletes“.

Ami viszont reménykeltőbb, hogy a fiatalok előszeretettel vásárolnak használtan, másodkézből online vagy vintage üzletekben. A fast fashion divatmárkák látják, hogy a Depop, a Vinted és az eBay a legnagyobb versenytársaik, és elkezdték értékes kiskereskedelmi területüket a használt ruháknak átadni. A Wear Next című tanulmány szerint, miközben a divatfogyasztás felgyorsul, ezzel párhuzamosan a lassú divat mozgalmának felemelkedését láthatjuk, a javítási forradalom (beleértve a javítási és átalakítási alkalmazásokat, mint például a Sojo és a The Seam) és a DIY divat további virágzását. Reméljük ezen az úton fogunk továbbhaladni!

Forrás: theguardian.com

Fordította: Pölz Klaudia

Míg a divatbemutatók önmagukban az iparág környezeti hatásának csak egy kis töredékét teszik ki, Rachel Arthur szerint a divatbemutatók a bolygót károsító túlfogyasztást tápláló marketinggépezet középpontjában állnak.

Racher Arthur tanácsadó, író és az ENSZ Környezetvédelmi Programjának fenntartható divatért felelős vezetője és az ő cikkét adjuk közre magyar fordításban.

Az elmúlt hetekben a divatszakma visszaáramlott Párizsból, a luxusipar kétévente megrendezésre kerülő női divathét utolsó és legpompásabb állomásáról.

Vásárlók, hírességek és influencerek százai repültek oda benzinfaló repülőjáratokon, hogy egy pillanatra bepillantást nyerjenek az új kollekciókba, amelyeket gondosan megmunkáltak egy olyan elavuláshoz, amely azt jelenti, hogy mindenki hajlandó lesz újra repülőre ülni, és hat hónap múlva újra megismételni az egészet.

Az biztos, hogy az ezekkel a nagyszabású marketing pillanatokkal közvetlenül összefüggő kibocsátások és hulladékok csepp a tengerben az iparág teljes lábnyomához képest. Az évek során a márkák és a divattanácsok erőfeszítéseket tettek mindkettő csökkentésére.

A bemutatók közvetlen hatására való kizárólagos összpontosítás azonban figyelmen kívül hagyja a nagyobb képet: a divat negatív környezeti és társadalmi hatásának középpontjában a túltermelés és a túlfogyasztás áll. És mit tesznek a divathetek, ha nem mindkettőt táplálják? Vegyük csak a közelmúltbeli New York-i, londoni, milánói és párizsi rendezvények sorát, nem is beszélve a gyakran túlzó módon megrendezett és elő-őszi kollekciókról – minden egyes bemutató beindít egy marketinggépezetet, amelynek célja az új termékek vásárlásának ösztönzése. Az események által inspirált trendek, az általuk biztosított médiaérték és végső soron a vásárlás, amelyre mindezek ösztönöznek, táplálják a környezeti hatásukat.

Ez a divatbemutatók úgynevezett “agylenyomata”: a kifutón való megjelenésnek a fogyasztásra gyakorolt hatása.

“Ha a lábnyomod a működésedet írja le, akkor az agynyomod azt írja le, hogy az embereket milyen érzésekkel töltöd el. Ez az Ön kulturális lenyomata” – mondta Lucy Shea, a Futerra változási ügynökség csoport vezérigazgatója.

A divatbemutatókra költött milliók nem csak a kifutó kollekciók értékesítését mozdítják elő, hanem a szomszédos és könnyebben hozzáférhető termékek – a táskáktól az illatokig – sokkal szélesebb körű fogyasztását ösztönzik, valamint a tömegpiaci másolatok iránti keresletet is.

A reklámipar felismerte ezt a dinamikát. A Purpose Disruptors, egy korábbi reklámszakemberekből álló szervezet, amelynek célja az éghajlatváltozás katalizálása, bevezette a reklámozott kibocsátás fogalmát, amely a kampányok által generált forgalomnövekedés mérésére utal. Ez azt mutatja, hogy a reklámok 32 százalékkal növelik az Egyesült Királyságban minden egyes ember éves szén-dioxid-kibocsátását.

Talán szükségünk lenne egy ezzel egyenértékű elszámolási folyamatra a divatmarketing számára. Nevezzük el “trendkibocsátásnak” – egy olyan mód, amellyel mérhető a luxus imázsépítés által vezérelt fogyasztás hatása.

Ez azért fontos, mert a divat csak akkor fogja elérni fenntarthatósági céljait, ha csökkenti az eladott termékek mennyiségét. De a luxus agynyomása – a divatbemutatóktól kezdve a szerkesztőségi fotózásokig, reklámkampányokig és influencer posztokig, amelyeket elősegítenek – jelenleg az ellenkezőjére ösztönöz, arra buzdítva a vásárlókat, hogy vásároljanak a villámgyorsan változó trendeknek

Ezt az ENSZ Környezetvédelmi Programja és az ENSZ Éghajlatváltozással foglalkozó szervezete a Fenntartható divatkommunikációs útmutatóban (Sustainable Fashion Communication Playbook) https://www.unep.org/interactives/sustainable-fashion-communication-playbook/ állapította meg. Ez egy felhívás a túlzott fogyasztás üzeneteinek felszámolására, beleértve a hagyományos divatbemutatókat is, és ehelyett a fenntartható fogyasztás irányába kell terelni az erőfeszítéseket.

Ennek nem kell a divathetek halálát jelentenie – ahogyan a fenntartható divatágazat sem követeli meg a divat teljes megszűnését. De mindkettő radikális változást igényel.

Az olyan bemutatók, ahol milliókat költenek a gazdagság pillanatnyi és extravagáns fitogtatására (mindezt azért, hogy a kapcsolódó márka- és médiaértékből további milliókat nyerjenek vissza), nem aktuálisak egy olyan időszakban, amikor iparágként hozzájárulunk a bolygórendszerek eróziójához, amelyektől a túlélésünk függ, és eközben emberek millióit sújtjuk, főként a fejlődő országokban.

Ez áll a középpontjában annak, hogy Amy Powney, a fenntarthatóságra összpontosító Mother of Pearl luxusmárka kreatív igazgatója miért nem tart többé divatbemutatókat.

“Az éghajlati összeomlás idején ez durvának és szükségtelennek tűnt” – mondta. Ehelyett arra kellene használnunk az ilyen alkalmakat, hogy támogassuk és ünnepeljük azokat, akik megmutatják, hogy másképp is lehet.

A koppenhágai divathét az alternatív megközelítés egyik példája: A tervezőknek 2023-tól 18 konkrét fenntarthatósági követelménynek kell megfelelniük ahhoz, hogy bemutatót tarthassanak. Többek között nem szabad megsemmisíteniük a korábbi kollekciók eladatlan ruháit, a bemutatott ruhák legalább felének jobb anyagokból kell készülnie, és a márkáknak vállalniuk kell, hogy platformjaikat a vásárlók oktatására és tájékoztatására használják a fenntarthatósági gyakorlatukról. Bár van még hova fejlődni, más nagyvárosokkal összehasonlítva ez egy nagy nyilatkozat.

Most azokra van szükségünk, akik ismét nagyobb léptékben gondolkodnak arról, hogyan mutassuk be a divattal való kapcsolat új módjait. Végül is ez már nem a fokozatos változás ideje. Az átalakulást fel kell turbózni, új rendszereket és üzleti modelleket kell kifejleszteni – olyanokat, amelyek nem arra épülnek, hogy egyszerűen egyre több és több új dolgot adnak el, és nem gondolnak az emberekre, a bolygóra, sőt a profitra gyakorolt hosszú távú hatásokra. A divatbemutatók újragondolása ennek része.

A divat maga is felismerte a változás szükségességét. A világjárvány idején az iparágon belül egyre többen kérték, hogy reformálják meg a divathetek könyörtelen forgását, ami a független tervezők számára pénzügyileg bénító lehet.

Ahelyett, hogy a platformok egy elavult, elromlott rendszert táplálnának, a divatheteknek lehetőséget kellene adniuk egy új rendszer elképzelésére. A márkáknak arra kellene használniuk őket, hogy rávilágítsanak a megoldásokra, valamint hogy felemeljék és ösztönözzék a tudatos fogyasztás körüli törekvéseket. Erre már vannak példák. Az idei szezonban Párizsban Stella McCartney a kifutón tartott bemutatóját az alacsonyabb környezeti terhelésű anyaginnovációk piacával egészítette ki. New Yorkban Maria McManus tervező a bemutató végeztével a közönséggel együtt végigvezette, hogyan készültek az egyes darabok a fenntarthatóság jegyében.

Ünnepeljük azokat is, akik a körforgásos megoldásokat helyezik előtérbe; azokat, akik a hulladékot erőforrássá alakítják, és arra ösztönzik a fogyasztókat, hogy szeressenek bele az olyan fogalmakba, mint a használt és újrahasznosított divat. Egy párizsi divathét csereboltja, amelyben a szokásos első soros versenyzők is részt vennének, nem csak hatalmas nyilatkozat lenne, hanem talán az egyik legnagyszerűbb divatbemutató, amelyet a mai divatipar valaha is látott.

Itt van egy kreatív lehetőség arra, hogy az ember használja az agylenyomat erejét, és új utat kovácsoljon. Bár a kreativitást nem szabad korlátozni, azt feltétlenül át kell irányítani.

Did you miss some of the events that we got involved in this month? Not to worry, here is what we did early this October.

Fashion Revolution Philippines (FashRevPH) marked the World Circular Textile Day with a series of events. World Circular Textile Day is celebrated each year on October 8 but one day was not enough for this year 2023.

Exhibit and Bazaar at Eastwood Plaza

FashRevPH joins an exhibit and bazaar at Eastwood Plaza in Quezon City with WearForward and Restore. The event featured a well-curated selection of sustainable fashion brands, a clothing swap party with free consultation on sustainable fashion practices, and a showcase of upcycled pieces from Jan Paul Martinez, a local fashion designer. This activity ran from October 6 to October 10.

The Challenges and Opportunities in Textile Waste

Tere Arigo, FashRevPH Country Coordinator, facilitated the virtual panel discussion titled “Closing the Loop: Navigating the Challenges and Opportunities in Textile Waste.” Top industry figures from diverse backgrounds joins the panel discussion. The panel started off with FashRevPH spokesperson Prince Jimdel Ventura of WearForward followed by Noreen Baustista the co-founder of Panublix, joined with her is a fashion educator and sustainable designer Irene Subang, with a professional wardrobe stylist and author of Always Be Chic Miss KC Leyco and lastly Lester Dellosa an environment activist who is also the founder and creative director of CICCADA.

The time for discussion of environmental and economic challenges posed by textile wastes in the Philippines was not enough. It included the innovative solutions that can transform these issues into opportunities for circular fashion materials, processes, business models, products, services, and consumption were too broad to talk about in just an hour.

Capacity Building Workshop on Textile Circularity

FashRevPH collaborated with MakeSense Philippines in a Capacity Building Workshop on Textile Circularity on October 13, 2023. The workshop was held at BSA Twin Towers in Ortigas Center, Mandaluyong City.

FashRevPH participated in the workshop to talk about local textiles and sustainable fashion with Mr Ventura as part of the panel in the first part of the program. The organization guided the design of one of MakeSense’s capacity-building workshops in partnership with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

FasRevPH’s Commitment to Sustainability

FashRevPH is committed to promoting sustainable fashion in the Philippines. The organization works to educate consumers about the impact of their fashion choices and to encourage them to support a more sustainable approach.

Overproduction, overconsumption and waste continues to be a growing challenge. It’s one caused by the global fashion industry’s linear ‘take, make, dispose’ model where mostly non-recyclable materials are extracted, made into products, and ultimately down-cycled, sent to landfill, exported through the global secondhand clothing trade or incinerated when no longer used. A crucial way to tackle textile and clothing waste is by investing in efforts to slow down consumption and increase clothing longevity, which would have a significant positive impact on the environment.

A growing number of major brands explain how they’re developing circular solutions that enable textile-to-textile recycling – 38% of brands in 2023, up from 28% in 2022, indicating a big jump from the previous year. Yet, less brands (29%) disclose their annual fibre mix and only 4% of brands publish the percentage of their products designed to enable circularity – which allows for the raw materials in disused clothes to be transformed into raw materials for new clothes.

Given that historically, major brands have released so-called ‘sustainable’ lines representing just a fraction of overall production, the absence of disclosed data on the quantity of a brand’s products that are truly circular does not inspire confidence. In order for these circular solutions to meaningfully contribute to addressing fashion waste, they need to become the norm rather than the exception in the industry. As a first step, greater transparency on brands’ fibre mix is crucial to understanding how to unravel the challenge of circularity.

To better understand the challenges facing the fashion industry, we invited a range of industry stakeholders and activists to provide in-depth analysis of the issues surrounding circular solutions and how governments and brands can adapt their strategies to create meaningful change. Here, you can explore some viewpoints featured in the Fashion Transparency Index 2023.

BUSINESS AS USUAL IS NOT VIABLE

JOSEPHINE PHILIPS, Founder and CEO, SOJO

It’s great to see more of the major fashion brands offering repair services, 26% this year compared with 20% in 2022 – as it not only shows a growing desire from consumers to partake in these practices, but also that brands are taking more accountability for their items post the point of purchase, promoting more circular behaviours.

While this moves the industry in the right direction, it’s important to note that shifting towards circularity needs to happen at every stage of the lifecycle of a product – not just at the point of disposal. For example, when garments are designed with longevity and end-of-life in mind, it entails a different approach towards material sourcing, ways of manufacturing, and end-of-life recycling. Another critical aspect is changing the narrative of how and what we buy. Ultimately, by continuing to pump out the same product volumes, we are not addressing the root-causes of textile waste – overproduction and overconsumption.

Using technology to streamline the tailoring and repair process allows SOJO to provide these services in an easy and accessible way, with online orders and door-to-door delivery of newly fitted or fixed items. The hope is that in the long term this will trickle down to changing consumer behaviour – decreasing consumption volume by helping people love their items for longer.

The British Fashion Council reports an estimated annual cost to brands of £7 billion caused by returns processes with approximately 30% of items bought online returned. With sizing or fit attributed as a leading factor in a customer’s decision to return (93%) and responding to the limited, generic sizing offered by most brands, our services help customers tailor their clothing uniquely to their bodies. In this way, care and customisation of garments happens not only at end-of-life, but also holistically throughout the lifecycle of the garments, supporting the reduction of waste through minimising returns and reverse logistic implications.

These two areas of focus for SOJO show that growing a business is not incompatible with championing a circular fashion industry. In other words, being better for the planet and people does not mean bad business. It’s a very exciting time to be part of the industry, however, scale is critical for creating systemic change. This calls for brands and investors to place bets and take risks to help champion these solutions. Ultimately it’s in their incentive to be part of this change, since it’s clear that the current business-as-usual mentality is not viable – for people, planet, nor profit.

YOUR WASTE, OUR PROBLEM: GLOBAL LANDFILLS WITH LOCAL CONSEQUENCES

MARÍA BEATRIZ O’BRIEN, COUNTRY COORDINATOR, FASHION REVOLUTION CHILE

This viewpoint was featured in the 2022 edition of the Fashion Transparency Index, and so the data has been updated to reflect this year’s findings.

The Atacama Region offers a landscape of unique beauty in earthy and soft colours. The Altiplano Plateau near the Andes Mountains is home to an ancestral and rich textile culture of camelid wool and local iconography.

A world away, the global textile industry based on a fast fashion system continues to accelerate overproduction and overconsumption. Clothing is also massively under-utilised and socially devalued in a race for cheap garments and ever changing trends.

The 1980s marked a new economic model for Chile. Once a strong and proud manufacturing country, the eruption of free market policies made it impossible for the national textile industry to compete with low-cost imports. It encouraged the sale and import of second-hand clothing. Free trade agreements in the 1990s deepened and cemented the model.

The Atacama Desert is the second largest textile landfill in the world. Iquique is the capital of the region and a tax-free port, a point of entry for Chile and neighbouring countries, especially Bolivia. Most bales come in unsorted and the regional government has banned throwing textiles in the local trash. Every year, thousands of tonnes of imported clothes must end up somewhere.

Out of sight is out of mind. Rich countries can export their waste to low-income countries; wealthy neighbourhoods can do the same inside their own territories. Alto Hospicio is a poor community of land seizures and self-built houses. Around 50 landfills are dispersed throughout the area, with little chance of clothing recovery. Picture a scenery of silence; a place where time seems to stand still. Open land where people and nature fade away–a perfect spot to dump and forget.

According to the Fashion Transparency Index 2023, only 12% (30/250 brands) of brands surveyed disclose the quantity of products produced during the annual reporting period, a disappointing drop from last year; In 2022, the data corresponds to 15% (38/250 brands). Without knowing how much is produced, it’s hard to control and hold brands accountable for the items dumped in landfills worldwide.

In Alto Hospicio, clothes leak chemicals into the ground and synthetic microfibres scatter through the air and into the ocean. Water and air are highly polluted, especially because incineration is a common practice. The Index shows very small efforts being made in publishing annual progress on the reduction of synthetic materials deriving from fossil fuels. In 2023, 27% (67.5/250 brands) disclosed this information, up from 24% (59/250 brands) last year.

The Atacama Desert landfill shows the scale of the global waste problem of the fashion industry. For the region, this is an environmental and social disaster. Current national import legislation is lax and has made it impossible for the local industry to resuscitate, suffocated by thousands of tonnes of unwanted clothing from the rest of the world. The region has the right to determine its own textile sovereignty and develop a local economy based on ancestral knowledge and creative design practices, such as the local strong up-cycling movement and sustainable independent designers trying to shape a new national industry.

*Some information included in this viewpoint was provided by Desierto Vestido, a civil society organisation in Iquique raising awareness on the impact on the Atacama Landfill.

WE CANNOT RECYCLE OUR WAY OUT OF OVERPRODUCTION

EMILY MACINTOSH, Senior Policy Officer for Textiles, European Environmental Bureau

The European Parliament recently adopted the EU ‘Textile Strategy’ – a policy plan to bring down the environmental and social impact of Europe’s textile consumption, with a focus on fashion and clothing. And while the approach contains good intentions, it remains to be seen whether its flagship actions on waste prevention will stop the most polluting business practices.

More and more used garments are set to be collected by local authorities when new EU rules requiring separate collection of textiles come into force in 2025. To finance this collection, the EU is working on plans for brands to pay fees that cover the costs of managing their products once they become waste, through so-called Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes.

But what happens to collected textiles? While we might imagine donated clothing is all reused in Europe, in fact 1.4 million tonnes of used textiles with no EU market value were exported to third countries like Ghana and Kenya in 2020 alone, causing devastating environmental, economic, and human rights’ impacts.

And collecting more garments from 2025 in Europe will mean more and more items entering the global used clothing trade. That’s why money raised through EPR fees must go beyond paying for collection and sorting activities in Europe and support fair remuneration for communities in the Global South who receive exports of clothing castoffs from the EU.

The fees must also be set so they make a meaningful impact on reducing the volume of clothing produced every year because it is overproduction that is the root cause of the climate, environmental and social impacts of clothing consumption. We cannot allow brands to pay to pollute for a minimal fee. In other words, policymakers can ‘eco-modulate’ the fees by rewarding business practices rooted in sufficiency, quality, fairness, and transparency with a lower fee, and penalise those built around throwaway fashion, exploitation, and opaque supply chains with a higher one.

And with only 12% of brands currently revealing how much they produce, there is an opportunity to incorporate this obligation into EPR rules to make disclosure of data around how many products companies put on the market annually – and where they are produced – mandatory.

Because we cannot recycle our way out of overproduction. Overblown green claims on recycling hide the reality that the infrastructure and technology to turn ever-increasing volumes of clothing back into clothing is virtually non-existent, and the recycled fibres that do appear in ‘eco’ ranges make minimal environmental gains.

It’s only by remunerating workers properly at all ends of the supply chain as part of strategies to reduce volumes that we can ease the strain fashion is putting on our planet.

You can read more about overconsumption, waste and circularity in the 2023 edition of the Fashion Transparency Index.

Header image: Tim Mitchell & Lucy Norris from our Loved Clothes Last zine

Fashion Revolution Week is our annual campaign bringing together the world’s largest fashion activism movement for seven days of action. It centres around the anniversary of the Rana Plaza factory collapse, which killed around 1,138 people and injured many more on 24 April 2013.

This year, as we marked the tenth anniversary of the Rana Plaza factory collapse, we remembered the victims, survivors and families affected by this preventable tragedy and continue to demand that no one dies for our fashion. To define the next decade of change, we translated our 10-point Manifesto into action for a safe, just and transparent global fashion industry. Our campaign platformed the work of our diverse Global Network who provided local interpretations of their chosen Manifesto point(s). We believe that while fashion has a colossal negative impact, it also has the power and the potential to be a force for change. Together, we expanded the horizons of what fashion could – and should – be.

Here, catch up on some of the week’s highlights and find out how to stay involved with our work, all year round.

Remembering Rana Plaza

Fashion Revolution Week happens every year in the week coinciding with April 24th, the anniversary of the Rana Plaza disaster. On April 24th 2013, the Rana Plaza factory building in Bangladesh collapsed in a preventable tragedy. More than 1,100 people died and another 2,500 were injured, making it the fourth largest industrial disaster in history. On April 24th, we paused all other campaigning to pay our respects to the victims, survivors and families affected by this tragedy, and came together as a global community to remember Rana Plaza.

As we reflect a decade on, we are inspired by and celebrate the progress made in the Bangladesh Ready-made Garment (RMG) sector by the Accord. The International Accord on Fire and Building Safety was the first legally-binding brand agreement on worker health and safety in the fashion industry and is the most important agreement to keep garment workers safe to date. This year, we pay tribute to the joint efforts of all Accord stakeholders who have significantly contributed to safer workplaces for over 2 million garment factory workers in Bangladesh, including the Bangladeshi trade unions representing garment workers, alongside Global Union Federations and labour rights groups. We welcome the introduction of the Pakistan Accord and would like to see the adoption and success of the International Accord replicated in all garment producing countries.

Manifesto for a Fashion Revolution

Our theme for Fashion Revolution Week 2023 was Manifesto for a Fashion Revolution. Back in 2018, we created a 10-point Manifesto that solidifies our vision to a global fashion industry that conserves and restores the environment and values people over growth and profit. This year we called on citizens, brands and makers alike to sign their name in support of turning these demands into a reality, boosting our signature count to 15,500 Fashion Revolutionaries and counting. We are immensely grateful to everyone who has and continues to sign; our power is in our number and each signature strengthens our collective call to revolutionise the fashion industry.

To campaign for systemic change in the fashion industry, we themed the week around complementary Manifesto points, providing ways to be curious, find out and do something daily around each of them. From supply chain transparency to living wages, textile waste to cultural appropriation, freedom of association to biodiversity, we shared global perspectives and solutions to fashion’s most pressing social and environmental problems.

Over the past ten years, the noise around sustainable fashion has only got louder. But meanwhile, real progress is too slow in the context of the climate crisis and rising social injustice. That’s why Fashion Revolution Week 2023 was an action-packed and future-focused campaign that amplified the actions and perspectives of Fashion Revolutionaries around the world.

View this post on Instagram

Global Conversations

To capture these global perspectives, we launched the Fashion Revolution Map on Earth Day, which coincided with the start of Fashion Revolution Week. Developed by Talk Climate Change, the Map served as a global forum to reflect on the week’s themes and events, using our Manifesto as a talking point. Fashion Revolutionaries continued the discussion offline by inviting their family, friends, colleagues and classmates to imagine what a clean, safe, fair, transparent and accountable fashion industry would look like with us. These conversations were then recorded on the Map as a source of inspiration and knowledge exchange.

Anyone can be a Fashion Revolutionary; it starts with a simple dialogue about the changes you want to see in the fashion industry. Make your voice heard by contributing to our map today and help change the fashion industry through the power of conversation!

View this post on Instagram

Good Clothes, Fair Pay Highlights

Ten years on from Rana Plaza, poverty wages remain endemic to the global garment industry. Most of the people who make our clothes still earn poverty wages while fashion brands continue to turn huge profits. At Fashion Revolution, we believe there is no sustainable fashion without fair pay which is why we launched Good Clothes, Fair Pay as part of a wider coalition last July. The Good Clothes Fair Pay campaign demands living wage legislation at EU level for garment workers worldwide, building on Manifesto points 1 and 2.

During Fashion Revolution Week, our EU teams coordinated awareness events, campaigns and marches to mobilise signatures for this campaign. On April 25th, we headed to the European Parliament with Fashion Revolution Belgium to demand better legislation in the fashion industry. The day of action consisted of a panel discussion between Members of the European Parliament and impacted fashion stakeholders, and ended with a stunt outside the Parliament. Fashionably Late highlighted that the EU is running out of time to act on poverty wages in fashion. This stunt was replicated by our teams in Germany, France and the Netherlands throughout Fashion Revolution Week to demonstrate EU-wide solidarity with the people who make our clothes.

We have less than three months left to collect 1 million signatures from EU citizens to push for legislation that requires companies to conduct living wage due diligence in their supply chains, irrespective of where their clothes are made. If you are an EU citizen, sign your name here. If you’re unable to sign, please support the campaign by sharing it far and wide online.

View this post on Instagram

Fashion Revolution Open Studios Highlights

Fashion Revolution Open Studios is Fashion Revolution’s showcasing and mentoring initiative since 2017. Through exhibitions, presentations, talks, and workshops with emerging designers, established trailblazers and major players, we celebrate the people, products and processes behind our clothes.

This Fashion Revolution Week, Fashion Revolution Open Studios joined forces with Small but Perfect to spotlight the work of 28 European SMEs taking part in their circularity accelerator project. Forming part of this European events programme, Fashion Revolution Open Studios held a two-day event in partnership with The Sustainable Angle and xyz.exchange at The Lab E20. The event showcased seven innovative designers from the Small But Perfect cohort of sustainable SMEs and displayed how they are embedding circular solutions into their work, from crafting grape leather handbags to developing community approaches to making and working together. Alongside the exhibition, there were livestreamed webinars, workshops and panel discussions to explore the projects and hear about some of the the challenges facing small businesses and the industry at large in switching to circular business models.

Global Network Highlights

With 75+ teams from all around the world, Fashion Revolution Week 2023 championed the perspectives and contributions of our Global Network. Here are just a small selection of highlights from our country teams:

Fashion Revolution New Zealand unpacked each Manifesto point with industry trailblazers in an Instagram Live series.

Fashion Revolution teams in Bangladesh and Sweden co-organised a virtual panel discussion on shifting consumer behaviour.

Fashion Revolution Singapore celebrated the launch of their digital zine MANIFESTO.

Fashion Revolution teams in Iran and Germany collaborated on Women, Life, Freedom, a joint exhibition.

Fashion Revolution Nigeria shared the stories and journeys of local slow fashion brands.

Fashion Revolution Argentina invited us to join their Wikipedia edit-a-thon.

Fashion Revolution teams in Vietnam, South Africa and Scotland hosted local community clothing swaps.

Fashion Revolution India won the Elle Sustainability Award for Eco-Innovation in Fashion.

Fashion Revolution Uganda brought together the country’s top designers and brands at Kwetu Kwanza.

Fashion Revolution teams in UAE and Canada both held local design competitions for students.

Fashion Revolution Hungary championed the revival of traditional folklore practices in clothing and fashion.

Fashion Revolution USA discussed the fashion industry’s impact on people and planet in a 2-part Zoom series.

Fashion Revolution Uruguay hosted Fashion Celebrates Life, a community picnic themed around Manifesto point 10.

Fashion Revolution teams in Chile and Portugal shared their Fashion Revolution Week highlights with us on Instagram Live.

You are Fashion Revolution

We are so grateful to everyone in our community for getting involved in Fashion Revolution Week on social media and beyond. Every single voice makes a difference in our fight for a fashion industry that conserves and restores the environment and values people over growth and profit.

While Fashion Revolution Week 2023 may be over, our community, our campaigning and our movement continues, 365 days a year. Please join us in fighting for systemic change by:

Following us on social media: Stay up-to-date by following us on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, LinkedIn and YouTube, and signing up to our weekly newsletter.

Finding your country team: Connect with the teams in your region by following them online, attending their events and volunteering with them. Find your country team here.

Using our online resources: Our website is a treasure trove of information, from how to guides and online courses to annual reporting on transparency on the fashion industry. Get started here.

From all of us in the Fashion Revolution team, we appreciate your support and we look forward to seeing you next year!

Artículo redactado por Nora Sesmero Andrés, voluntaria de Fashion Revolution.

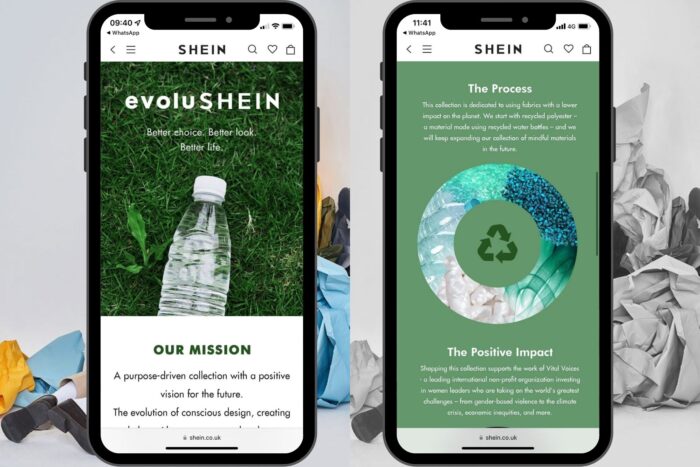

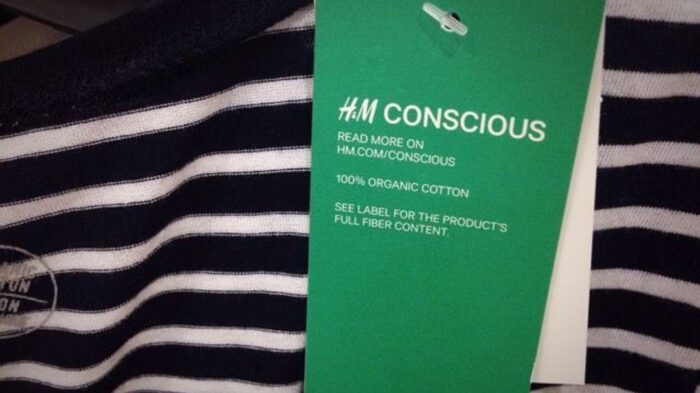

El greenwashing es una práctica de márketing destinada a crear una imagen ilusoria de responsabilidad ecológica y de sostenibilidad medioambiental por parte de una empresa. Según Vogue México, estas empresas usan términos como “consciente”, “orgánico”, “eco” o “sustentable” para definir sus productos aunque sus maneras sigan siendo abusivas y contaminantes. Un ejemplo de estas actuaciones son las marcas que pertenecen al fast fashion o moda rápida, las cuales llevan a cabo este greenwashing manteniendo una producción masiva que no resulta sostenible.

El ISEM Fashion Business School comunica que hay una parte invisible en la industria de la moda para el consumidor, esta corresponde con la cadena de valor de un producto. Aunque parece que actualmente los datos de este sector están dejando de ser invisibles. Algunas empresas han sido denunciadas por emplear greenwashing en sus campañas de marketing, como Inditex, H&M, Primark, Nike, Adidas, New Balance, Gucci, Dolce & Gabbana, Lacoste, Decathlon, Asos, Boohoo, etc., tal y como muestra el informe “Los numerosos lavados de reputación de la industria de la moda” de Carro de Combate, el Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets (ACM) o la Autoridad de Competencia y Mercados de Reino Unido (CMA).

El portal de moda sostenible, Vesti la Natura afirma que las fibras sintéticas se incluyen en más de dos tercios de los materiales usados en la industria textil. El material más utilizado es el poliéster, fibra que proviene del petróleo y que no es bueno que esté en contacto con la piel. A principios de año, Bloomberg publicó un informe donde se especifica que el 92,5% de la ropa estudiada de Shein contiene plásticos. La empresa lanzó la colección evoluSHEIN, que incluía tallas inclusivas y materiales sostenibles, esto se puede considerar como una acción de greenwashing.

De esta manera, algunas marcas realizan publicidad engañosa y tratan de confundir al consumidor. Entonces, ¿cómo puede detectar el consumidor el greenwashing? “La sostenibilidad está de moda y las grandes cadenas lo aprovechan para vender más. Cuando una empresa es sostenible de verdad tiene información amplia, contrastada y visible en sus webs. Creo que el mejor consejo es ser críticos y cuestionarnos, trataría de ser responsable con mi consumo. La insostenibilidad de la moda comienza en el volumen que se produce, mi consejo es tratar de analizar qué es lo que hay detrás de las empresas a las que solemos comprar, buscaría información sobre sus impactos medioambientales y sociales”, comenta la fundadora de Slow Fashion Next, Gema Gómez.

El consumidor tiene la posibilidad de informarse antes de hacer una compra, leyendo la etiqueta de las prendas y tratando de profundizar en la información que muestra una empresa. Cuanto más grande sea una marca, más difícil le será cambiar su estructura a una más sostenible. En el blog de Slow Fashion Next comparten que los usuarios podrían consultar si una organización hace donaciones en defensa del medio ambiente, preguntar qué procesos, requisitos o regulaciones ambientales están llevando a cabo o comprobar si forman parte de un Directorio que garantice que cumplen con un mínimo de requisitos.

La directora del máster en Comunicación, Gestión de Marca y Sostenibilidad en la Industria de la Moda de la Universidad Internacional de Cataluña, Elisa Regadera, explica que las redes sociales serán de gran ayuda en esta época, ya que harán posible que se le pidan explicaciones a las empresas ante las acciones que realizan. Además, tendrán un papel fundamental para tomar decisiones en favor del consumo circular: “Las RRSS son el lugar donde ‘vive’ la generación actual y ‘vivirá’ la futura”, afirma esta experta.

En los últimos años ha crecido la preocupación por el modo en que las empresas afectan a la sociedad a nivel social y medioambiental, y con ella, la necesidad de una comunicación transparente sobre la sostenibilidad. Pero, ¿cómo pueden contribuir las empresas a una comunicación auténtica sobre su compromiso con la sostenibilidad? Según la periodista y especialista en consumo y sostenibilidad Brenda Chávez, la clave para evitar el lavado verde es que los gobiernos regulen, las empresas dejen de utilizar estas tácticas y los consumidores sean conscientes de ellas para poder denunciarlas.

La industria y su impacto en el medio ambiente son temas que están en constante debate. Ante esta situación, Regadera plantea: “Considero que las condiciones de salud, seguridad y los salarios de las personas deberían ser el primer objetivo de la industria. Respecto a sus impactos en el planeta (cambio climático, recursos hídricos, ecosistemas, etc.), cualquier intervención para reducir el impacto en los procesos —desde el diseño y desarrollo de producto, la selección de materiales, así como todo lo relacionado con la fabricación, envasado, transporte, almacenamiento y distribución, consumo y devoluciones— produciría avances para combatir el cambio climático. Lo importante es trazar y conocer bien la propia cadena de suministro, decidir por dónde empezar y en qué se va a ser más responsable, aportando los datos con transparencia”.

Carro de Combate aconseja a las empresas evitar la exageración u ocultar información para hacer lavados verdes, creen que las compañías deberían defender cambios y demostrar soluciones a las personas, así como destacar y celebrar nuevos modelos a seguir. Vesti la Natura añade que estas deberían implicarse en la investigación de materiales de origen biológico y en una moda más circular, defienden que se tendría que abordar el problema de la producción de baja calidad y la moda rápida, que las marcas incluyeran además la obligación de adoptar la debida diligencia, tanto en términos de “derechos humanos” como de “violaciones ambientales”. Por último, plantean una pregunta a las grandes empresas: ¿Hasta cuándo seguirán haciendo afirmaciones falsas hacia sus clientes?

Gracias a la Ley 7/2022, de residuos y suelos contaminados que incumbe a la industria textil española, se están regulando nuevas medidas para que las empresas textiles se encarguen de sus desperdicios. “Las marcas deberán pensar en la donación, alquiler, reparación, venta de ropa de segunda mano, customización, etc. En el caso de no decantarse por estos nuevos modelos de negocio, deberán pensar dónde y cómo van a deshacerse, empaquetar y/o gestionar esos residuos, sin enviarlos a vertederos, otros países, etc. También deberían pensar en el ecodiseño, para no desperdiciar los restos de prototipos y demás. La tecnología también ayudará a poder introducir de nuevo en la cadena de producción aquellos tejidos que no estén mezclados y puedan dar lugar a nuevas prendas: reciclaje textil. Y por supuesto en cómo gestionar con sus proveedores las aguas residuales de fábricas, etc. Pero como la legislación obliga en el ámbito español y no siempre en los países de producción, esto seguirá estando pendiente”, comparte Elisa Regadera. En el marco de la COP25, Gabriela Figueiredo, presidenta del regulador portugués, señaló “la existencia de una guía a nivel europeo sería lo mejor porque los inversores tienen miedo del greenwashing. Este marco regulatorio tendría como ventaja el desarrollo de una información ‘entendible’ y ‘creíble’”.

Elisa Regadera introduce el pasaporte digital que “contribuirá a que las marcas sean transparentes en la trazabilidad de su cadena de valor a través del blockchain. Esto permitirá a las marcas hacer un seguimiento de sus procesos y detectar cualquier tipo de alteración, pudiendo corregir y/o hacer más eficiente su cadena. En los casos de marcas de lujo o artesanales, permitirá combatir también las falsificaciones. Y la misma información podrá ser conocida por el consumidor: a través de un código de barras, QR o algo similar adherido a las etiquetas o a las mismas prendas, tendrán acceso a toda la información. También podrá añadir otros contenidos relacionados con la marca, los cuidados de la prenda, eventos, etc. que se podrán consultar mediante este medio. Pero todavía queda un poco para que esta práctica se extienda, ya que pocas marcas tienen todavía acceso a la tecnología blockchain”. Figueiredo cree fundamental encontrar una solución “pragmática” para que este contexto no suponga una “avalancha” de información.

Parece que el greenwashing no desaparecerá próximamente, pero tanto consumidores como empresas podrán poner de su parte para hacer que esto suceda pronto. En los últimos años está creciendo el interés por parte del consumidor hacia la sostenibilidad y si su demanda crece, se regulará la situación.

Si te interesa seguir leyendo y concienciándote acerca de la actualidad de la industria textil, pulsa aquí.

Ecocide.

Few words hold as much power as this one. Ecocide comes from the Greek oikos, which means home; and the Latin occidere, which means to kill. To kill our common home: that is the literal meaning of this mysterious word.

View this post on Instagram

Legally, ecocide is defined as the most serious crimes against the environment. To be more specific, an International panel of experts, initiated by Stop Ecocide International, defined ecocide as “unlawful or wanton acts, committed with knowledge that there is a substantial likelihood of severe and either widespread or long-term damage to the environment being caused by those acts”.

In concrete terms, what are we talking about? Recurring oil spills, the ongoing mass deforestation of the Earth’s primary forests, the emission by only 100 companies of 71% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions between 1988 and 2015…

These ecocides are the reason for the current ecological and climate crisis. They endanger our capacity to live on this Earth. Yet, to this day, they remain unpunished. Criminal law at the international level, or in most national law, simply does not recognise the crime of ecocide, and lets the people responsible for them free of any accountability.

This is what a 50 years old movement of activists, lawyers and elected representatives from all around the world is trying to change, and the mobilisation is growing! More and more countries, or their parliaments, are supporting the recognition of the crime of ecocide. Citizens are rising to ask political leaders to act to put an end to these crimes and protect the environment and our human rights.

Today, on March 20 2022, citizens all around Europe, in Brussels, Paris, Rome, Amsterdam and Madrid, and around the world are mobilising to ask for the recognition of ecocide in the European Union and at the international level.

What does it have to do with fashion? Well, everything, because recognising ecocide will make companies from all sectors change their behaviour to better take into account the environment.

We know that the fashion industry is a massive polluter. It is the third sector that consumes the most water in the world. It emits every year 1.2 billion tonnes of greenhouse gas, about 10% of the world’s emissions. 500 000 tonnes of microplastics are thrown in the ocean each year due to the production of clothes. And as usual, what endangers the environment also endangers humans: 60 million women textile workers worldwide are exposed to hazardous and toxic chemicals, including pesticides, on a daily basis.

In Bangladesh, rivers are turning black due to the sludge and sewage produced by textile dyeing and processing factories. In Chile, 39,000 tonnes of clothing waste are being stocked in the Atacama desert.

Recognising ecocide and all environmental crimes in law will enable us to prevent these crimes before they happen. It will force companies to change their behaviour, in order not to face criminal sanctions.

Recognising ecocide also means recognising that the destruction of the Earth is one of the most serious crimes, and cannot be ignored anymore. The symbolic power of such recognition should not be underestimated.

As the European Union is currently working on revising its environmental criminal law, I will work tirelessly to include the recognition of ecocide in the text. If you want to support this fight, sign the European petition and share your support on social media with the hashtag #StopEcocideEverywhere.

Together, let’s put an end to ecocide.

Related articles

Fashion brands’ leather sourcing practices are driving deforestation

Fashion unites on a call to action for COP26

Further reading on ecocide

- What is ecocide?

- Making ecocide a crime

- Ecocide: Should killing nature be a crime?

- How a global ecocide law could hold polluters to account

For the third year running, Fashion Revolution’s Black Friday campaign will call for an end to overproduction, overconsumption and waste in the fashion industry. We want citizens to take a stand against mindless consumption, combat fashion’s culture of disposability and exploitation, and say no to the Black Friday and Cyber Monday sales.

“Black Friday is a scam. It’s one more way to get citizens to think they are finding a bargain, when in fact they are hunting an illusion. Black Friday is about the rush, the speed, the compulsion. At Fashion Revolution we are asking you to stay conscientious and to buy with purpose.”

Orsola de Castro, Fashion Revolution co-founder and creative director

Black Friday represents fashion’s systemic overproduction problem, with big brands thoughtlessly churning out new products at the cost of people and the planet. Brands get away with this wasteful business model because cleverly marketed seasonal markdowns mean their customers help them get rid of unsold stock. An estimated 100 billion pieces of clothing are made each year, but according to our 2021 Fashion Transparency Index, only 14% of major fashion brands publish the quantity of products they produce. Meanwhile, only 27% of major fashion brands say they are investing in circular solutions such as textile-to-textile recycling, and just 32% have clothing take-back schemes in place.

The majority of the people who make our clothes live in poverty. In fact, Oxfam estimates that it would take a major fashion CEO just 4 days to earn what a female garment worker in Bangladesh will earn in her entire lifetime. We want to see an end to this hyper-discount culture where there is so little value placed on clothing, the resources used to produce it or the people who make it. We, as consumers and as global citizens, deserve better from our wardrobes.

Citizens can take part in the campaign by abstaining from shopping Black Friday sales where possible, choosing alternative ways to have fun with fashion like upcycling, repairing, swapping and sharing. They can also help spread the message that overproduction costs the Earth on social media, holding brands accountable by asking #WhoMadeMyClothes? and #WhatsInMyClothes?, and supporting the movement for positive change by donating to Fashion Revolution.

During the Black Friday weekend (26th – 29th November 2021), a series of sustainable fashion brands, retailers and rental platforms are pledging to donate 5-15% of their sales instead of promoting discounts that encourage unsustainable practices of overproduction and overconsumption.

We know that the end-of-season sale model is ingrained in many brands, but we need forward-thinking businesses to buck the Black Friday trend and empower people to choose quality over quantity instead. This crucial support helps us to fund our work campaigning for a transparent and accountable fashion industry.

The Black Friday campaign is supported by Fashion Revolution’s global network of 90+ country teams, alongside organisations working to shape a better fashion system: Fashion Act Now, Global Fashion Xchange, Slow Fashion Movement. Collective Fashion Justice, Fashion Impact Fund and Fashion Takes Action.

To learn more and take part, visit: www.fashionrevolution.org/blackfriday

This is a guest blog post by The OR Foundation, a movement for a justice-led circular economy. During Second Hand September, we shared a range of ‘Myth vs. Fact’ content unpicking some common misconceptions about the secondhand clothing trade. We also hosted a panel event, Solidarity in the Secondhand Supply Chain, featuring key stakeholders from across the industry to build constructive debate on the future of resale and recycling.

Myth #1: The global secondhand clothing trade is charity. The global secondhand clothing trade is recycling.

The global secondhand clothing trade is a supply chain. It is an expansive for-profit business network that represents the primary source of clothing for over half of the global population.

The secondhand clothing trade has long been marketed as charity, but it has always been a for-profit outlet for the Global North’s excess. Clothing is not given out for free to those in need. You might donate your clothing for free, but it still costs money to collect, sort, grade, stock, resell and transport secondhand clothing and the people investing money in those activities expect to make a profit in return.

Secondhand retailers in the Global North can only sell about 10-20% of what they collect in the country of consumption. Most of the clothing donated in the Global North will pass through multiple hands in multiple countries before ultimately being exported to the Global South where retailers purchase individual bales. Retailers in Kantamanto spend between $75-500 per bale, many taking out loans to purchase the clothing.

While you may look at the Made In tag on your clothing to define the ‘country of origin’, for many people in the Global South, the country of origin is the country from which the secondhand bale was exported. Just as there is a value chain of farms, mills and factories that participate in manufacturing new clothing, so too is there a chain of brands, consumers, charities, resale platforms, graders and exporters that make up the secondhand supply chain.

Today many brands are rebranding the secondhand clothing trade by using the language of “recycling” or “circularity”. Typically when people think of recycling they think of old garments being turned into new garments, but the majority of what is collected by most brands is simply diverted into the secondhand clothing trade, with the bulk of these items being exported to the Global South. Many garments are resold and upcycled through resale markets like Kantamanto, but nearly just as many become waste. Kantamanto sees 15 million garments a week, and 40% leave as waste. The clothing that is exported to secondhand markets in the Global South is not recycled into new textiles.

Framing the secondhand trade as either charity *or* recycling centres the perspective of the sender (the person giving away an item) and perpetuates an abstract, depoliticized narrative that confuses people and provides an excuse for overproduction and overconsumption. Understanding the secondhand clothing trade as a supply chain pushes us to ask the same questions of the secondhand trade that we ask of the new clothing trade, including questions about the labour involved. Questions like:

- Who sorts the clothing that I drop in my neighbourhood bin?

- Is their job safe?

- Who resells my clothes?

- Do they earn a living wage?

- What is my role within this value chain?

- Is the clothing I buy worthy of many lives?

Understanding the labour involved in today’s system of recirculation is the first step in ensuring safe and dignified employment opportunities in the circular economy of the future.

Myth #2: Waste resulting from the secondhand clothing trade should be the responsibility of those who demanded it.

The global secondhand clothing trade is a legacy of Colonialism and exists within the over-supplied chain of new fashion as an outlet for people to buy more new clothes.

Under colonial rule, Ghanaians were expected to conform to professional dress codes as defined by the British. In order to enter certain rooms, to get certain jobs, attend certain schools or to be considered a ‘modern global citizen’, Ghanaians had to forgo their local dress in favour of Western clothing, swapping out sustainably made kente for a shirt and tie. Colonialism created the conditions for conformity. Navigating oppressive colonial rules is a survival mechanism, not an expression of demand. Colonisers profited from those rules by selling hand-me-downs and importing used clothing. This evolved into the secondhand trade we know today.

The global secondhand clothing trade is supply-driven, not demand-driven. The type of garments and quality of clothing available to traders in the Global South is entirely dependent on the quality and care of clothing being produced, purchased, returned, worn and donated in the Global North. The supply-driven nature of the secondhand economy impacts everyone along the value chain, including resale platforms, consignment stores, charities, clothing collectors, graders and exporters in the Global North, but ultimately all of these actors can choose to pass less desirable clothing down the chain to importers and retailers in the Global South.

Generally, importers cannot order a container full of the exact bales that they want and they do not see the specific items they are purchasing. Importers have little negotiating power over what is shipped and they assume that up to ⅓ of the clothing on each container will be difficult to sell (eg. bedsheets, single-use tees and winter clothing) and will likely become waste.

No segment of the fashion industry accurately predicts demand, hence the existence of deadstock and unsold goods. Given the unpredictable nature of clothing donations, the resale economy cannot accurately predict stock levels. But Kantamanto has no outlet for its excess – it is the last link in the oversupplied chain.

Secondhand fashion and textiles have the potential to transform the industry for good, but at present, we are turning blind eye to the hidden actors in the supply chain. The people who sort, recycle and resell our unwanted clothes, and the often unjust systems that underpin their work. The garments that end up as waste in landfill, and the consequences of these rotting fashion mountains on the natural world.

It’s time for a more mindful approach to how we buy, sell, resell and recycle clothing

Myth #3: The secondhand trade stops new fast fashion from being desired and sold.

The oversupply of cheap secondhand clothing teaches people that clothing is disposable and primes people to become consumers of new fast fashion. The secondhand clothing trade is seen as an outlet for fashion excess and therefore must operate at the scale and pace of the new clothing industry. Secondhand clothing markets are overwhelmed with cheap fast fashion items. The never-ending supply of non-durable items drives down the perceived value of clothing.

Secondhand retailers struggle to invest in rehabilitating lower quality items, and must keep buying more low-quality clothing to pay off the losses from previous bales. Waste accumulates in the market and in the environment. It is a vicious cycle, one that teaches citizens that clothing is a disposable commodity.

The more the Global North floods the Global South with disposable clothing, the more prolific the attitude that clothing is meant to be cheap and disposable.

Low-quality garments become desirable when brands convince people that investing in convenience is more important than investing in quality. This is bad news for local independent designers and good news for foreign fast fashion companies looking to expand to new markets.

As more people enter the middle class in Ghana, they are ordering clothing from major global retailers, not shopping from local designers.

There is no evidence that the abundant supply of secondhand clothing in the Global North has slowed down the consumption and production of new garments, and there is no evidence that the exportation of secondhand clothing to the Global South has eliminated any desire for new clothing. Instead it has primed new markets to become consumers of fast fashion.

Myth #4: Fashion’s waste crisis is caused by a lack of textile recycling technology.

Fashion’s waste crisis is caused by the exploitation of workers and of resources. Disposable fashion is only profitable because the people who make our clothes are not paid a living wage and environmental damage isn’t factored into the price tag.

Fiber-to-fibre recycling is absolutely necessary, but any brand that attempts to blame fashion’s waste crisis on a lack of recycling infrastructure is greenwashing. Brands are not adequately investing in the textile recycling technologies that already exist, and it could also take years before these technologies are able to absorb a meaningful amount of fashion’s excess.

Recycling is not a silver bullet solution that offsets the overproduction of garments and the exploitation of everyone from garment workers to secondhand retailers. We can’t tackle fashion’s waste crisis if the majority of people working in fashion from factories to secondhand markets are indebted to the very system that is exploiting them.

Circular solutions could be the key to a more sustainable fashion industry. But any brand that prioritizes recycling over ensuring that the people growing, sewing, repairing, reselling and upcycling our clothes are earning a living wage is not interested in solving the problem. When brands continue to overproduce while paying lip service to circularity, they are not interested in solving the problem, they are interested in extracting profit from the problem.

The fashion system is built on waste and exploitation, but that waste is not factored into the price tag we see in shops and online stores. We stand for a fair and equitable fashion economy for the people paying the true cost.

Myth #5: Secondhand clothing ends up as waste in the Global South because it is unwearable.

Today, new clothing can be acquired for as little as used clothing, and the resale market is saturated with both new and “like-new” garments. This means that any small defect or sign of wear makes a garment less desirable and less profitable amid a sea of other options.

There are fewer high quality, made-to-last items in circulation, and with the rise of resale in the Global North, more of these items are being extracted from the flow of secondhand goods. This leaves secondhand graders and exporters in the Global South with more low grade items. Roughly 25% of the clothing that enters Kantamanto every week is single-use t-shirts from marathons, hen-dos, conferences and family reunions, many of them faded and stretched.

When retailers in Kantamanto open a bale, they assess the goods, sorting the clothing into four piles called selections. While retailers can sometimes end up with a bale that is completely spoiled due to mould or odour, most bales contain less than 6% trash. This means that 94% of every bale is deemed wearable by Kantamanto retailers. And yet 40% leaves as waste.

Why does so much secondhand clothing end up as waste? In Kantamanto there are two main reasons ↓

1. Kantamanto shoppers know that there is a never ending supply of goods coming through the market. With this in mind, many people buy only the first selection, which is “like new” and makes up only 18% of the average bale. If a retailer is out of first selection, the customer would rather come back the next day when there is a new bale than buy the remaining lower quality garments. Basically, one man’s trash is not another man’s treasure, it’s just trash, regardless of whether it is wearable or not.

2. Because of the decreasing quantity of first selection goods per bale, many retailers have less money to invest in rehabilitating lower quality garments (like a stained and stretched marathon t-shirt) through cleaning, ironing, dyeing, tailoring or upcycling. Instead, retailers have only one option to maintain cash flow — buy another bale. To make room for more stuff they have to get rid of old merchandise. People in need will pick over the waste piles at the end of the day, but there are still far more garments than can even be given away for free. Thus, wearable clothing goes to waste.

There is no market capable of absorbing the excess produced by the fashion industry. The secondhand clothing trade adds an important link to fashion’s supply chain, extending the life of billions of garments every year, but it does not close the loop. The only way to ensure that all garments reach their potential is to slow down production of new clothing and invest in the sharing economy to enable enhanced cleaning, mending, altering and upcycling of what already exists.

Learn more

Solidarity in the Secondhand Supply Chain

The burden of excess: It falls on her

Modern colonialism disguised as donation

Dead White Man’s Clothes

Fashion Revolution Week is the time when we come together as a global community to create a better fashion industry. It centers around the anniversary of the Rana Plaza factory collapse, which killed 1,138 people and injured many more on April 24, 2013.

This year, as we marked eight years since the tragedy, Fashion Revolution Week focused on the interconnectedness of human rights and the rights of nature. Our campaign in the USA amplified unheard voices across the fashion supply chain and harnessed the creativity of our community to explore innovative and interconnected solutions.