Artículo redactado por Nora Sesmero Andrés, voluntaria de Fashion Revolution.

Humana Fundación Pueblo para Pueblo es una organización sin ánimo de lucro que se encarga del reciclaje del textil en España. Los ciudadanos españoles nos desprendemos al año de 1’2 millones de toneladas de ropa, y eso tiene un gran impacto en el medioambiente.

Si por algo destaca Humana es por ser una organización transparente. En su web podemos encontrar toda la información trazada para que el ciudadano de a pie conozca cómo trabajan.

Esta fundación se dedica a reinsertar en el ciclo de vida las prendas de las que los consumidores nos desprendemos, aunque no dan abasto. De las 1’2 millones de toneladas de prendas que los ciudadanos españoles desechan al año, actualmente solo se recicla un 10%. Otros proyectos en España como Moda re- se dedican también a esta labor.

Humana tiene 5200 contenedores de donación de ropa repartidos por España, promoviendo que los consumidores donemos nuestra ropa cuando creamos que realmente ya no la podemos vestir, aprovechando todo su potencial. En sus plantas de reciclaje de Madrid y Barcelona, donde se puede acudir para conocer cómo trabajan, se observan pilas y pilas de sacas de ropa prensada. Algunas de esas sacas pesan alrededor de unos 400kg.

Cuando los ciudadanos dejan sus bolsas de ropa en los contenedores de Humana, estas se transportan a sus plantas de reciclaje y mediante un proceso rápido y efectivo se clasifican según su estado para dotarlas de un nuevo uso. Un 90% de estas son destinadas a la venta de segunda mano tanto en España como en los países donde realizan sus programas sociales.

De esta manera, tratan de fomentar la moda de segunda mano, a partir de la venta de ropa en sus tiendas, donde según muchos de sus clientes, podemos encontrar prendas completamente nuevas. Esto demuestra la mala educación que tiene el consumidor de moda a día de hoy. Por ello, creen que es importante educar a este en la sensibilización, que seamos conscientes del impacto que tienen nuestras compras. “Dado que las calidades de la moda rápida son pésimas, las prendas que se reciclan también son cada vez de peor calidad”, afirma el responsable de comunicación de Humana, Rubén González. La solución pasaría por dejar de consumir este tipo de moda y comenzar a invertir en prendas de calidad.

Parte de los beneficios que esta fundación produce se destinan a realizar proyectos sociales en países del sur, relacionados con la educación, la salud, la agricultura, el cambio climático, el desarrollo comunitario, etc. En países como China, Ecuador, Laos, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Senegal, Zambia y España. En 2020, sus proyectos de cooperación involucraron a cerca de 125.000 personas.

Algunos de los proyectos de educación se encargan de formar a profesores de primaria en el entorno rural, ya que defienden que los profesores bien formados, motivados y comprometidos son la mejor palanca para hacer avanzar la educación. Impulsan la agricultura urbana, ecológica y sostenible, además del desarrollo rural. En el ámbito de la salud, tratan de educar a las personas para prevenir el VIH. En 2021 se ha profundizado en el fortalecimiento de los programas relacionados con cambio climático y del trabajo junto a socios especializados. Esta labor contra las consecuencias del calentamiento global tuvo su prolongación en la COP26 de Glasgow, en la que Humana participó para compartir la experiencia acumulada mediante los programas Farmers Club, establecer lazos con otras entidades y detectar oportunidades para seguir promoviendo acciones en favor de la adaptación y la mitigación de las consecuencias del cambio climático.

Humana ha convertido un oficio antiguo, el de los traperos, en una manera de hacer que la moda sea circular y financiar con ello distintos proyectos sociales.

A partir de 2025, el reciclaje de ropa será obligatorio en la Unión Europea. Esto produce una sensación de esperanza, ya que será menos probable que encontremos imágenes como la del mercado de Kantamanto, en Ghana. Es importante poner el foco en lo que aún queda por mejorar, y la reducción de la producción y el consumo son claves para hacer que la industria de la moda de un salto hacia la sostenibilidad.

Otra de las tareas pendientes consiste en que las prendas que se produzcan sean de un solo material. Debido a que reciclar ropa de diferentes composiciones es un trabajo complejo y caro.

La organización trabaja en el fortalecimiento de iniciativas de I+D+i para prolongar el ciclo de vida del textil y el calzado y, al mismo tiempo, multiplicar sus posibilidades de reaprovechamiento, en el marco de la economía circular y la jerarquía de residuos. Por ello, más allá de la preparación para la reutilización, la Fundación colabora en España con diferentes asociados en el impulso de proyectos de diversa naturaleza, desarrollando de modo conjunto soluciones concretas en aras de impulsar una mayor circularidad en la gestión del textil usado. Como su participación como miembros impulsores del Pacte per a la Moda Circular de Cataluña o su reciente adhesión al Consejo Asesor del proyecto Life Kanna Green, nacido para proponer y definir un nuevo modelo de consumo y economía circular para el calzado, basado en los principios del ‘Cradle to cradle’, donde nada es un residuo.

Otros de los objetivos de Humana son: conseguir abarcar más cantidad de ropa para poder reciclarla, optimizar sus procesos de reciclaje, ampliar el número de tiendas, generar empleo, avanzar con sus proyectos sociales, trabajar con otras empresas del sector de la reutilización, ayuntamientos, etc. Su mensaje es positivo, creen que vamos hacia una moda sostenible, mucho más regulada e inteligente.

Si quieres leer el anterior artículo de la autora, pulsa aquí.

This is a guest blog post by The Love Is Project

The Love Is Project empowers female artisans in developing countries across the world by selling on their intricate work, supporting them with fair pay, food, healthcare and education. Today we want to highlight the importance of educating girls and women and how it benefits them and their greater communities.

Almost a year ago, we wrote in our Love In Juala, India blog post that in addition to donating essential supplies to our artisans, we were in talks with village leaders to provide the women with a tutor to teach them reading, writing, and financial literacy. Now that the lockdown in India has been lifted, we are happy to announce that the program has started and there are currently 33 female students in the class.

Stationary and period products were distributed to help the women and girls continue their education and stay in school. Topics of conversation included how to keep dengue fever from spreading in the community and encouraging women to get the COVID-19 vaccine. The women also discussed how to maintain good hygiene during menstruation, the regressive divorce system in the region, and how Muslims and Hindus were able to coexist peacefully in the village.

These women aren’t letting anything stand in their way of providing a better life for themselves. More than half of them don’t have electricity, and the majority of them don’t have access to clean drinking water. A few of the women have achieved a 5th grade education, but most of them have never been enrolled in school. The women are proving that there is no better time than the present to learn financial literacy. We are so proud of our artisans and excited to see what they achieve.

Our artisans have created an eye-catching bracelet with colours reminiscent of the prized spice saffron. When you purchase a bracelet from the India Collection, you are supporting the education and livelihood of our female artisan partners.

Further Reading

This is a guest post from Outland Denim, a business founded to offer opportunity, financial freedom, education, and support to women who have come from backgrounds of exploitation or vulnerability.

Header image: Amy Higg Photography

Fashion’s opportunity to be a force for good

Here is something to think about: If we were to abolish modern slavery, we could put a serious dent in climate change at the same time.

Modern slavery is defined as situations where offenders use coercion, threats or deception to exploit victims and undermine their freedom. It is estimated to affect 40.3 million people globally, including 1 in every 130 women and girls.

Not only is modern slavery a gross neglect of human rights, it is also one of the world’s largest greenhouse gas producers, according to Kevin Bales and Benjamin K. Sovacool of The Rights Lab, Nottingham University. In fact, if modern slavery were a country it would be the 3rd largest emitter of carbon dioxide in the world after China and the US.

Bales and Sovacool state, “Abolishing slavery is shown to be one of the most effective instruments for climate change mitigation, especially given that the costs of ending slavery seem on par to about $20 billion, or the expense of a single large nuclear power plant.”

The effects of climate change are also felt heaviest in communities that are already vulnerable, causing a cycle of social and environmental harm.

So, what does any of this have to do with fashion? Sadly, a lot.

According to the Global Slavery Index, $127.7 billion garments at-risk of containing modern slavery in their supply chains are imported by G20 countries each year. Fashion is ranked second in terms of the industries that pose the highest risk.

One thing we want to make clear is that modern slavery does not always equal worker exploitation or underpayment, they are nuanced issues and each situation is as individual as the human it impacts. But, both are exploitation and occur in the same supply chain ecosystem, and so when organisations are forced to look into modern slavery in their supply chain, it’s the first step to identifying any kind of worker exploitation no matter the category it falls under.

Brands, in particular, are understandably nervous to invest in looking for these instances of exploitation in their supply chains. It’s expensive in terms of both financial and human resource investment, there are cultural and language barriers to navigate, strong relationships to establish, and of course to actually publicly uncover instances of exploitation would traditionally be a PR disaster.

However, we believe the next step in brand accountability and transparency is to shift toward a culture that is not afraid to uncover these instances of exploitation. Because without identifying them, we cannot fix them.

Collaboration is critical to making this investment accessible. With this in mind, we recently partnered with Precision Solutions Group, Bossa Denim, and our direct competitor Nudie jeans to establish a program to offer support to one of the fashion industry’s most vulnerable segments being cotton farming communities. Through this program, we get to build stronger brand-maker connections, identify possible issues, and share costs with partners. Plus, we can confirm that in no way has this program pitted us or Nudie against each other!

This brings us to the question of once exploitation, modern slavery, or vulnerability to either has been identified, what can be done to combat this?

Combatting Modern Slavery

Opportunity for safe and stable employment is key, and this is the foundation upon which Outland Denim was created. The idea being to support women who have come from backgrounds of modern slavery, exploitation, or vulnerability, not with charity, but safe employment, a living wage, education, and healthcare, that in turn allows them to support their family and contribute to the prosperity of their wider community. It’s nothing above-and-beyond. Incredible things will happen when we simply do the bare minimum in providing people the human rights and support they deserve.

In talking to one of our first staff members about three years into her working with us we asked, ‘How is this helping you; this kind of employment and opportunity?’ She went on to say that because of this opportunity she’d been able to build a home for her family who previously lived under a plastic sheet. She went on to say that she was also able to buy her sister back off a man who owned her.

This model has proven to be transformational in the lives of our team members, and they are proof that fashion has the ability to uplift individuals, families, and whole communities.

View this post on Instagram

Here are just a few of the lives that have been touched by Outland Denim wearers.

“When I think about my work with Outland, I have so much pride. Before, I did not think I had the option to work, but now I am able to not only work, but excel! I have learnt how to sew shirts and jackets, and teach others who are new. These jeans are my love. Every day I put my love into them.” – Reasmey

Before I worked at Outland my family and I had a lot of debt. It was difficult to plan for our future. Now, I am debt free! And am able to sponsor my nephew to go to school. My strength comes from my children; I want them to have the opportunity to study and have a better life. – Rom Chang

My life has changed since working with Outland. Here everybody shows respect for each other. I have learnt how to make many new styles, I have been able to save more money and, with the education programs, my Khmer and English has improved. I would like to share my story with people in bad situations – maybe one day my story and experiences could help others. Thank you. – Achariya

We are just one brand, but reimagining the way we as a society do ‘fashion’ we can uplift whole communities, mitigate climate change, and at the same time influence other industries with large social injustice issues like electronics, fish, cacao, and sugarcane to follow suit.

In practice, this means an industry that:

- Partners with researchers and lawmakers fighting for human rights regulation and legislation in supply chains;

- Offers opportunities to people who are considered vulnerable who may find difficulty in securing employment;

- Invests in mapping whole supply chains and builds long-term relationships with their suppliers;

- Has robust living wage requirements;

- Collaborates (even with direct competitors) to find solutions, shares costs, and shows that it’s not a competitive disadvantage to do so;

- Does not put the onus on consumers to do the research, or disrespect them through greenwashing;

- Demonstrates that all of the above can be done while still being economically successful and meeting shareholder’s expectations.

It may sound like a utopian goal, one far out of reach. But the fact is the fashion industry is worth $3 trillion – and with that kind of economic power we as an industry can either do a lot of harm, or a lot of good.

References:

- Global estimates of modern slavery: forced labour and forced marriage — Executive summary

- Stacked Odds Report, Walk Free Foundation 2020

- From forests to factories: How modern slavery deepens the crisis of climate change by Kevin Bales and Benjamin K. Sovacool. Energy Research & Social Science, 77, available online 20 May 2021, 2214-6296/© 2021 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license

- Global Slavery Index ,Walk Free Foundation

Further Reading

Garment workers and climate change: The socioeconomic link

Human rights, transparency and accountability in fashion: A conversation on Uyghur forced labour

Marking Human Rights Day: How legislation can help protect the people who makes our clothes

The Garment Worker Protection Act, also known as SB62, was signed into law by California Governor Gavin Newsom late September. The new landmark law will bring much needed reforms to California’s fashion industry and has the potential to impact the future of fashion on a national and global scale.

With SB62’s historic passage, California will now prohibit the use of the piece-rate system, as the main form of pay, an industry-wide practice of paying workers by the number of garment units produced or operations completed. Reports have shown that garment workers compensated through piecework are significantly underpaid and overworked, earning as little at $2.68 per hour and an average wage of $5.85.1 Under the new law, workers are ensured fairer wages and guaranteed a minimum hourly wage. Piece rate is still allowed as a bonus incentive on top of the hourly rate, to incentivize productivity, and for workers organized under a Collective Bargaining Agreement.

Most notably, the Garment Worker Protection Act holds fashion brands and companies jointly and severally liable for wage violations. This joint liability provision of the bill – and perhaps the most revolutionary and controversial aspect – extends liability to the upper echelons of the supply chain. Fashion companies, not just the factories, manufacturers, or subcontractors, can be held liable for unpaid wages. This type of legal liability for fashion brands has never been implemented anywhere in the state of California.

The fight for SB62 to become law has been a long journey, and its passage is a historic win for the labor justice movement. The bill failed in the previous legislative session, and this year, opposition and certain business groups came out swinging and branded the bill as a “job killer.” But for many garment workers, the Garment Worker Protection Act was a call for justice, dignity, and a better future.

Maria Del Carmen, an organizer and worker-leader with the Garment Worker Center (GWC), a worker rights group that led the charge to pass SB62, stated:

“After 30 years in garment, I am fighting for SB62. We want the law to pass to hold brands accountable and so that all garment workers can live with dignity. This law would have the impact on my life of getting out of extreme poverty.”

Maribel Alvarado, another organizer and worker-leader from the GWC also stated:

“This law would make me very happy not just for me but for all the people coming [into the industry] after me. First because SB62 would end the wage theft of minimum wage, second because it will help to respect our rights, and third because we will be heard!”

Garment Worker Center (GWC) member-organizers Maria Del Carmen and Maribel Alvarado joined the GWC to fight wage theft and other labor violations they and thousands of other garment workers experience daily while working in this sector. Understanding the root cause of their exploitation led them to organize and participate in campaigns for brand accountability and policy changes like SB62. This worker-led campaign inspired organizations and communities across the fashion industry and brought allies from all different sectors to join their efforts, gaining support from immigrant, religious, union, business, and policy and legal groups, as well as fashion companies, businesses, creatives and designers.

Matthew DeCarolis, an attorney with the Employment Rights Project at Bet Tzedek, commented on how garment workers organized and campaigned for SB62:

“This started with the workers. Any change that happens starts at the grassroots level and starts with the workers themselves. The status quo was not acceptable, and the garment workers brought their causes to our elected officials. The substance of the bill came from them and their lived experiences.”

Despite being touted as a potential “job killer,” SB62 received tremendous support from businesses with over 150 ethical brands standing behind the bill. The new law will allow them to remain competitive in the industry. For many companies who have already been paying fairer wages, the Garment Worker Protection Act will help level the playing field against those who have been exploiting a broken system.

Bo Metz, Founder and Creative Director of Bomme Studio, a Los Angeles full-package clothing manufacturer, stated why fashion companies like Bomme Studio support the new law:

“It’s basic decency to treat others as you would like to be treated. Exploiting garment workers for ridiculous corporate margins is not sustainable and unethical. Enough is enough.”

Regarding the future of sustainability and the fashion industry in California, Bo further stated: “Because of SB62, California now has a strong path to claiming the mantle as the number one most sustained apparel manufacturing hub.”

For many brands and companies, the new law will be a key piece to securing the fashion industry’s future in the state and forward into the 21st century. In addition to the garment sector, California’s fashion economy is linked to many adjacent industries and key sectors, all closely operated and located within the state and the city of Los Angeles. The state’s unique landscape, locale, and intersection of networks makes it a prime location for more circular economies and circular models of production.1

Matthew DeCarolis further provided: “There’s a reason why the garment manufacturing center is in LA. The skilled workforce, the garment workers are here. All the supply networks are here. It’s a landscape of relationships, as well as infrastructure, textiles, fabrics, business, and designers.”

With the passage of the new law, many businesses believe that the “Made in LA” and “Made in California” labels will also be revitalized. The existence of sweatshop labor and sweatshop wages in Los Angeles’s backyard tarnished the city’s reputation. SB62 will bring back business and consumer confidence in the “Made in LA” label.

Christina Johnson, Co-Founder and Creative Director of Upcycle It Now, a Los Angeles design and manufacturing company, elaborated on SB62’s impact on the “Made in LA” and “Made in the USA” label:

“Customers can see quality differences in a product on a shelf but they can’t see if that product was sewn by an underpaid worker or not. They assume and trust that in the US there would be no way someone could experience the sweatshop working conditions from abroad. I feel SB62 was a way to bring awareness that even in the US there is wage theft and it also is a way to restore the trust we have that we don’t allow unfair practices flourish in the US.”

With the Garment Worker Protection Act taking effect this January 2022, its passage into law is a tremendous victory for the thousands of garment workers in Los Angeles, who are mostly women of color and immigrants. The law will help improve and transform their lives significantly.

Marissa Nuncio, Director at the Garment Worker Center, stated:

“With the passage of SB62, we’ve stood up and demanded corporate accountability from the fashion industry. Our world is changing in dramatic ways. Consumers and advocates know that sustainable, ethical business practices are non-negotiable at this point, and the passage of SB62 reflects that.”

Yet, even with the passage of SB62, there is still much work to be done to advance these protections and catalyze a more circular economy, in California and across the United States. Garment workers, advocacy groups and organizations in the fashion industry are already looking at how to stay organized after the passage of the new law. For instance, reforms are still needed with the Garment Restitution Fund, a fund that was established to help pay workers who were robbed of their wages.

Joanne Brasch, a Special Projects Manager from the California Product Stewardship Council (CPSC) stated how SB62 could help move CA towards a more circular fashion economy:

“Policies that promote a circular economy bring skilled jobs to the growing reuse, repair, and recycling sectors and it’s important that workers handling the materials, be it manufacturing or waste management, are protected.”

A massive victory for the labor rights movement and the fashion accountability movement, SB62 will also send out a message to the rest of the fashion world – a story about workers’ rights, human dignity, and justice prevailing against big corporate interests. Bo from Bomme Studio added: “I think there is going to be a long period of education and training. While this is now law there will need to be work to change culture and staying organized will help us do that.”

Sources:

- Garment Worker Center. (December 2020). Labor Violations in the Los Angeles Garment Industry.

This is a guest blog by the team behind the Garment Worker Diaries, an initiative from Microfinance Opportunities and SANEM that collects regular, credible data on the work hours, income, expenses, and financial tool use of workers in the global apparel and textile supply chain. The objective of the ongoing project is to help inform government policy decisions, collective bargaining, and factory and brand initiatives related to improving the lives of garment workers.

In this blog post, we meet Shila, a garment worker in Bangladesh, to discover how socioeconomic inequality is leaving women and children at disproportionate risk from the impacts of climate change.

View this post on Instagram

Shila was forced to leave her home when sea level rise contributed to its destruction. Her parents were unable to afford to continue paying for her education, so she became the caretaker of another family’s baby. Eventually, Shila found her way to Dhaka. She believes she was born sometime in the autumn of 1986, and she’s been a garment worker since 2000.

Shila is one of the 1,300 workers participating in the Garment Worker Diaries study, which has been conducting interviews with workers continually for the past 34 months, once per week, 52 weeks per year. Some respondents drop out of the study, others remain with us for a long time –Shila has been part of the study since June 2018. In late December 2020, she sat down with our film crew to discuss her life story, her daily routine, her work, and her aspirations for both herself and her son.

Shila’s story is at times tragic, mundane and uplifting. It’s unique, and we encourage you to watch the entire interview. But, there are other garment workers in much the same position as Shila. More specifically, there are many other female garment workers who have had and will have experiences similar to Shila’s—at the intersection of climate change, gender inequality, and the gruelling economics of global supply chains.

Like Shila, nearly 90% of the garment workers in Bangladesh migrate from somewhere else. Female garment workers are slightly more likely to migrate than male garment workers. While the majority of both women and men migrate for reasons related to economic hardship, men are slightly more likely than women to report that they migrated for reasons related to economic opportunity or because they prefer city-style living (as opposed to life in the villages). Women, on the other hand, are slightly more likely than men to say they were forced to migrate, and they are much more likely than men to report that they migrated to get married or to follow their spouse or another family member. We know this because in August 2020 we interviewed the workers participating in the GWD study about their migration experience.

View this post on Instagram

Also like Shila, workers are aware of the impact of climate change and the local effects of air pollution. A majority, 62%, answered “Yes” to the question “Are you concerned about climate change?” Here are a few of the reasons why, in their own words:

“People are being affected with various diseases and there are more storms and tidal surges due to climate change.” – Female worker, age 23, working in the garment industry for 3.5 years.

“People are being harmed economically. Crops are being damaged as there is no rain at the time when it is supposed to rain.” – Male security guard, age 50, working in the garment industry for 4 months.

“Black smoke emitted from cars, factories, and brick kilns is polluting the environment and people are getting sick from it. Medical treatment is very expensive. I fear that if this continues, it will be difficult for people to live a healthy life.” – Female machine operator, age 30, working in the garment industry for 12 years.”

The workers’ answers are consistent with what other data tell us: Bangladesh is consistently ranked as one of the most at-risk countries for weather-related events. Numerous advocacy groups, non-governmental organizations, academic journals and media outlets have been and will continue to call attention to the particular risk that Bangladesh faces.

But the workers are not well-equipped to deal with the consequences of climate change, and women workers, like Shila, are especially vulnerable. They have already migrated to improve their standard of living, but their earnings do not give them the financial cushion they may need to cope with the disruptions brought by climate change. For example, during the 12-month period from April 2020 to March 2021, the typical salary earned by female garment workers in Bangladesh was about Tk. 8,300, while the typical salary earned by male garment workers was about Tk. 10,100 (about USD $117/EUR €96/GBP £83).

If we look at the typical monthly work hours for female and male garment workers for that same time period, we see that women typically worked about 198 hours per month while men typically worked about 214 hours per month. This means on the whole that women earn about Tk. 42/hour to men’s Tk. 47/hour. Another way to put it is men earn about 12% more than women.

Shila, and workers like her, work long hours to make ends meet for wages that provide little buffer against the potential economic disruption of climate change. It is clear that human rights and the environment are deeply connected; the women who make our clothes and the children they raise could be disproportionately affected by the negative impacts of climate change. Watch the video below to learn more:

Further reading

International Women’s Day: Women’s rights and the environment in fashion

Fashion Revolution Podcast: Garment Worker Diaries

¿Como acceder al documental?:

1- Copia el siguiente código : GFENyRF8RbTF

(válido del 25 de abril al 27 de abril, o hasta completar 300 visualizaciones)

2- Accede a la siguiente página y pega el código allí.

https://online.docsdelmes.com/es/movies/machines

(Ten en cuenta que cada vez que alguien entra el código se descuenta una visualización, por favor no entres el código al menos de que querrás ver la película entera, para evitar quitarle la posibilidad de acceder a otra persona.)

Agradecemos al Consell de Eivissa por organizar esta actividad en el marco de la Fashion Revolution week Ibiza.

———–

SINOPSIS

Hipnótico, laberíntico y terrorífico. Miles de trabajadores exhaustos, largas jornadas de 12 horas y una enorme fábrica textil en Surat, una ciudad industrial del noroeste de la India. La cámara viaja, liviana, por los callejones de este submundo invisible donde humanos y máquinas son la misma cosa. Los sonidos expresivos generan un ritmo mecánico que nos acerca al mundo interior de los trabajadores.

El primer largometraje del cineasta Rahul Jain es valiente y personal. Las breves conversaciones que tiene con los trabajadores nos desaniman y añaden una nueva capa a una película que va más allá de denunciar la explotación laboral. Observamos, atónitos, una realidad dramática que nos atrapa con su exuberancia visual y sonora.

No dudes en dejarnos tus comentarios en instagram @fash_revspain.

Muchas gracias y buena visualización

Fashion Revolution España.

By Nathalia Orquera

Few people realize that Los Angeles is the center of the country’s garment manufacturing industry, housing the largest cut and sew apparel base in the U.S, most of whom are immigrant women from Mexico and Central America.

U.S. clothing factories employ about 200,000 people, with the greatest concentration in California. Los Angeles has more than 45,000 cutting and sewing operators alone, while in comparison, the New York City area employs less than 25,000 garment workers.

Garment workers in California face many of the same hurdles that garment workers overseas endure every day, from working in deplorable sweatshops condition, wage theft, abuse, to working an average of 55 hours a week with no overtime pay. Fast fashion is at the root of the many violations plaguing this industry. Cut and sew factories receive orders from large manufacturers often working for big brands, who are willing to produce items for little pay and with unrealistic manufacturer deadlines.

Despite the 1999 landmark Assembly Bill 633 (AB633) that sought to end wage theft in the garment industry, laws and protections continue to be circumvented so that retailers and manufacturers can avoid liability.

“This is a monumental occasion for the fashion industry and garment workers statewide because we haven’t seen any major reform to protect garment workers in over 20 years,” says Nicholas Brown, director of policy for Fashion Revolution USA. “This bill comes at a particularly crucial time, as many of these workers are facing the additional burden of exposure to COVID-19. California has the power to set the standard for safe, humane, and ethical labor practices in the garment industry that has the opportunity to be replicated well outside of Los Angeles.”

The new Garment Worker Protection Act (Senate Bill 62) co-authored by Senator Maria Elena Durazo and sponsored by Garment Worker Center, is a California bill that would improve working conditions in America’s largest garment industry by ensuring that brands share in the responsibility for garment worker pay under the law. SB62 would strengthen protections for garment workers in three essential ways by:

- Eliminating the use of the piece-rate system of pay, instead of ensuring that the legal hourly wage becomes the floor, not the ceiling, of wages paid to garment workers. The bill allows for incentive-based bonuses tied to productivity on top of the legal wage.

- Establishing multilateral accountability among brands and manufacturers for wage violations.

- Strengthening the authority of the Labor Commissioner’s investigation bureau to investigate and cite violations up the supply chain.

The piece-rate system compensates garment workers for each piece of clothing produced, as opposed to a set hourly wage. According to wage theft claims, some garment workers in L.A. are earning as little as $2.68 an hour through the piece rate system of pay, far below the LA minimum wage of $15 per hour for workplaces with 26 or more employees. According to the Garment Worker Center, the Covid-19 pandemic has only worsened their working conditions, where workers are often not given the time to wash their hands, factories are not sanitized between shifts or users, and bathrooms lack hand soap.

The California legislative cycle involves four different rounds of voting throughout the year. SB62 will start in a Senate subcommittee, get passed to the Senate, then the Assembly and then finally to the governor’s desk in the fall of 2021. On Monday, March 22, 2021, SB62 passed the CA Labor Subcommittee, which is the first vote in the process of getting this bill into law as it moves to the Senate Floor. On Tuesday, April 6, 2021, the bill passed through the Senate Judiciary Committee–the second of three committee hearings in the Senate, and another hopeful sign for the future of SB62. And on Monday, May 24, 2021, the bill passed through the full California Senate.

After the passing of SB62 in the Senate, the bill moved to the CA State Assembly to go through the committee process all over again in the second house. The Assembly made several amendments to SB62’s language, which had originally expanded upstream liability to retailers and brands.

On September 8, 2021, SB62 (with new amendments) passed the full CA State Assembly, only a few days shy of the September 10, 2021 deadline- the final day for any bill to be passed and the end of the 2021 legislative session.

However, this milestone and momentous victory of passing both houses was quickly eclipsed by last-minute political maneuvering. Despite receiving the backing of CA legislators, the bill was purposefully held and tied up in the Assembly, even after receiving a successful vote. SB62 needed to return to the Senate for a final approval of the amendments but had not been sent out of the Assembly.

On the last day of the legislative session, garment workers, fair wage and fashion advocates across the state, and organizations like the Garment Worker Center, Remake, PayUp, and FRUSA, began a late social media campaign and pressure to pass SB62. At the final hour, SB62 was finally resent to the Senate for final approval of the amendments and passed the full CA State Legislature. On September 17, 2021, SB62 was sent to CA Governor Newsom’s desk for the final step to become law, where it currently still awaits his signature or veto.

The fight to pass the Garment Worker Protection Act, SB62, is not over! Though SB62 passed the CA State Legislature, its fate currently rests with CA Governor Newsom, who has until October 10th to veto or sign bill.

Getting SB62 this far has come with many hurdles and truly has been a process decades in the making (with previous bills failing earlier in the past).

SB62 is a landmark legislation that has the potential to create industry-wide change by putting an end to the piece-rate system, paying fairer wages, and establishing basic workplace protections for CA garment workers.

To pass SB62, act now and contact Governor Newsom!

- Call Governor Newsom at (916) 445-2841.

- Urge him to stand up for garment workers and demonstrate his commitment to the minimum wage, fair working conditions, and corporate accountability by signing SB62 into law.

SB62 will become a historic step toward ending the modern sweatshop regime and will also help re-establish the United States as an epicenter of ethical manufacturing. As consumers we can help by holding brands accountable, understanding issues impacting garment workers’ rights, and sharing this information.

Join Fashion Revolution USA, Remake, and the Garment Worker Center in supporting California’s garment workers! Whether you live in the state of California or not, including residents of other nations, we encourage you to sign this petition and to share information about the importance of this bill with your friends, family and followers. And, watch “State of Play: Garment Worker Protections in the United States,” where we learned more of these key issues with Sen. María Elena Durazo, representing California’s Senate District 24; Dr. Elizabeth Segran, senior staff writer at Fast Company; Ayesha Barenblat, founder and CEO of Remake; Marissa Nuncio, director of Garment Worker Center; and Sarah Ditty, global policy director at Fashion Revolution.

Information for this article courtesy of Garment Worker Center and Remake.

In part two of our series on Rachel Breen’s “The Labor We Wear,” our Fashion Revolution USA Director of Operations and Community Ashleyn Przedwiecki interviewed fashion student Hannah Meidl on their takeaways from the exhibit. This Q&A has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

ASHLEYN P.: Can you share a little bit more about yourself? What inspired you to pursue fashion merchandising? Where are you currently in your education?

HANNAH MEIDL: I am currently a junior at St. Catherine University. I am majoring in fashion merchandising with a minor in business administration. Fashion has always been a passion of mine. It has been an outlet for self-expression as a visible representation of myself. I have always used it to communicate freely and purposely as to how I set myself apart. People use unique ways to show self-expression: for me, I have always used fashion. I also have a great appreciation for the evolution of fashion. By looking at the trends during a certain time period, you can learn the dynamics of what was occurring. As I started pursuing fashion merchandising at St. Catherine University, I became aware of the industry’s lack of consideration for the environment and its laborers. Our sustainably focused program at St. Catherine’s fashion department has brought these concerns to my attention. By learning more about the industry and the dire need for change, I have become very interested in learning and participating in changing the industry. I hope to take my education and background on this subject to further pursue change.

A.P.: You saw the exhibition, The Labor We Wear, at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, last fall. Can you describe your experience? Any emotions, sensations, or other aspects you want to share?

H.M.: On October 30th, 2020, I was able to see “The Labor We Wear” exhibition and I became extremely interested in learning more about the project. When I first entered the exhibition, my breath was taken away. The project was elegantly simple but spoke volumes; it told the story of everyone that has been impacted by the industry. By using visual representations of statistical facts of the workers and others affected by the industry, I was able to actually wrap my head around their turnover rates. It was extremely emotional to see all the hard work that the workers produce in a day for only a small fraction of the price they deserve.

A.P.: What elements of the experience had the biggest impact on you? What did you learn or take away from the exhibition?

H.M.: While attending school, I have become very aware of the harsh relationship between the industry and the workers. This exhibition was able to dive deeper into the daily hardships the workers have to endure. By representing the workers’ daily labor load, I was able to fully grasp how hard they truly work without fair pay, unsafe working conditions, and lack of representation. By looking at the clothing articles, it gave me chills to think about the workers behind the pieces. We as consumers are wearing their work. A human being is behind every piece of clothing in your closet and before buying and disregarding it, we as human beings need to think about the consequences.

A.P.: What do you think the artist (Rachel) wanted you to know through her work?

H.M.: My takeaway from her work is the need for change. The clear message of the exploitation in the industry of labor and resources is being addressed for all to be aware of. It is very easy to ignore or not make it your problem, but we longer look away. We are part of the problem and it can not be solved until we look at our contribution, and factor in ways to solve it.

A.P.: How has the experience challenged or changed the way you view your career in fashion?

H.M.: This has once again confirmed my passion for the industry. Fashion will always have a strong influence on our world. I have been interested in ways that the industry can still flourish while working towards a more sustainable future. While taking classes at St. Catherine University and experiencing exhibits like such, I have only grown more interested in how I can contribute to a positive change within the industry.

A.P.: As a student of fashion, what do you hope for the industry as you enter into your career?

H.M.: My career goal is to help make the necessary changes to the industry. I always knew that I wanted to be in the fashion industry, but I never knew my exact passion within it. Amazing artists like Rachel Breen and education programs that have brought attention to the importance of sustainability and ethics have opened my eyes to the harsh realities of the industry. I want to turn my passion into a way to keep the beloved industry alive while reshaping it to fit the needs of workers and the environment. Trust me, I love nothing more than shopping, but we must ask ourselves at what cost. There are plenty of ways to continue that love for fashion without the workers’ lives and environment for sake, we just have to learn to make that our priority. Lessening consumption and shopping sustainably are great ways to start the change. Your love for fashion does not need to change but rather evolve for the better.

Hannah Meidl is a Fashion Merchandising student studying at St. Catherine University in Saint Paul, Minnesota. She was born and raised in Manitowoc, Wisconsin, where she developed a love for fashion as a form of self-expression. When she began college a passion and focus on sustainability emerged. Upon graduation, she is eager to begin her journey in the fashion industry and encourage change to better our world.

Acerca de la denuncia hecha por una usuaria, sobre el uso de un llamado de auxilio hecho a través de la etiqueta en una de sus prendas de la colección GetOut perteneciente a la marca Streets:

En Fashion Revolution manifestamos un absoluto rechazo al uso de estrategias de marketing que tiendan a manipular la la reacción de los consumidores, banalizando las condiciones laborales y de seguridad que sufren o podrían sufrir las y los trabajadores de la confección, en cualquier eslabón de la cadena de suministro de la industria de la moda, en cualquier parte del mundo.

En la cadena de suministro de la moda masiva o fast fashion, las y los trabajadores al final de la cadena de suministro, en el proceso de las materias primas y la manufactura, sufren la mayor presión de la estrategia de producir mucho, más barato y con menor calidad la ropa que vestimos que tienen las grandes marcas.

Fashion Revolution, en conjunto con MFO crearon el “Diario de las trabajadores de la confección” un estudio de campo que recopila datos fiables y periódicos sobre las horas de trabajo, los ingresos, los gastos y el uso de herramientas financieras de los trabajadores en la cadena de suministro mundial de prendas de vestir y textiles en los países productores.

Adicionalmente a la calamidad sanitaria que ha producido la pandemia del Covid-19, los países que albergan las fábricas donde se produce la ropa masiva, están sufriendo las consecuencias de los cierres de fábricas y talleres junto con la presión que ejercen las grandes marcas, exigiendo menores precios para realizar sus encargos. Esto es particularmente evidente en Bangladesh.

Al comienzo de esta crisis las marcas dejaron de pagar los pedidos pendientes de entrega y aquellos comprometidos para el futuro, produciendo una ola masiva de despidos y movilizaciones migratorias, si antes las trabajadoras de la confección vivían en pobreza, ahora viven en pobreza extrema. La reacción de las organizaciones internacionales de la sociedad civil, no tardó en llegar. A través de la campaña #Payup (paguen a sus trabajadores), pudimos transmitir la indignación de las personas por la intolerable indiferencia de las marcas que, a pesar de todas estas consecuencias, deliberadamente dejaban de cumplir los compromisos más básicos. Con el pasar de los meses algunas marcas han regularizado esta situación, pero ahora nos enfrentamos a la relocalización de los puntos de confección y la manipulación de los precios

La publicidad a la que nos referimos en este comunicado, no refleja la intención de levantar una campaña responsable frente a una realidad que ha recrudecido el último tiempo, producto del aprovechamiento de las marcas para reducir los pagos a los talleres subcontratados. Debe haber un aporte y compromiso para luchar contra estos hechos, de manera sistémica y radical, para que esta forma de hacer industria, cambie.

Fashion revolution realiza cada año e Índice de Transparencia de la Moda, donde las grandes marcas muestran qué tan transparentes son con respecto a la información que tienen, entre otras tópicos, de las condiciones bajo las cuales trabajan las personas que están su cadena de suministro y en caso de encontrar falencias, qué están haciendo para cambiarlo. La divulgación pública nos invita a indagar y permite a la ciudadanía ejercer su derecho a obtener más información. La no divulgación perpetúa un sistema no inclusivo, en el que se espera que la ciudadanía confíe en las marcas que han seguido poniendo las ganancias y el crecimiento por encima de todo.

No es suficiente que la marca en cuestión se disculpe, o que París, la empresa que la distribuía, finalice el vínculo comercial. Las marcas deben tomar responsabilidad y no desentenderse, transparentando qué están haciendo para cambiar la situación de fondo y cuáles son sus compromisos, de manera concreta y transparente.

Fashion Revolution insta a las marcas y empresas minoristas a tomar con seriedad el tipo de comunicación que realizan y la información que entregan al público. La transparencia es la principal herramienta que tenemos, desde los consumidores hasta los trabajadores del final de la cadena de suministro y especialmente marcas y minoristas, para asegurar que las condiciones de trabajo, seguridad y salarios de las personas que hacen nuestra ropa, sean dignos y no perjudiquen su calidad de vida. Este debe ser el centro de la discusión, no otro.

Hoy más que nunca se hace necesario que las personas pregunten a las marcas #QuiénHizoMiRopa y exigir una respuesta transparente, para saber quién, dónde y en qué condiciones se hace su ropa.

An intimate look into the daily lives of women from the Garment Worker Diaries project in Cambodia and India.

Several women have given permission to share photos of their home life was part of a yearlong research study. We hope this helps the world better understand what it’s like to be a garment worker and inspires you to become an advocate for the people who make your clothes.

BANGALORE, INDIA

PHNOM PENH, CAMBODIA

This story was previously published in the first issue of our fanzine: MONEY FASHION POWER. Click here to browse our fanzine library.

The Garment Worker Diaries was a yearlong research project, led by MFO and supported by C&A Foundation, which is collecting data on the lives of garment workers in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India. Fashion Revolution will use the findings from this project to advocate for changes in consumer and corporate behavior and policy changes that improve the living and working conditions of garment workers everywhere.

Meet Dorcas Ndinda, aged 48, a part time farmer and green grocer, and the leader of her village weavers’ cooperative.

A lot of things bring me happiness. If my family has good health, I am happy and thankful. If the rains are in plenty, I am happy because I know that the harvest won’t fail. When I am leading a project and it is flourishing and the lives of the members are positively impacted, I am happy. Weaving, as well, makes me happy, especially when I look back and see how much my family and I relied on the income from the sales of baskets that I wove, when the rains failed and I had no produce to sell at my green grocery.

I’ve had to shoulder the responsibility of bringing up 3 children since my husband passed away in 1992. Prior to that, I stayed at home taking care of household chores while he provided for us. Since I didn’t proceed with my education beyond the primary school level, I knew that my chances of getting employed in a big town were very minimal, so I decided to try my luck at other ventures.

My village is located in a very arid area, therefore harvests are not guaranteed. However, I decided to double the crops I usually planted so that I could manage to feed my family and sell off the rest. The income from selling the produce wasn’t enough to cater for all of my young family’s needs. I knew about a few women from my village who would weave baskets and sell them. So I befriended these ladies, who taught me new weaving styles, and helped me perfect my skill. With the money I was earning from selling farm produce and the income from weaving, I was able to feed and clothe my family, and with the help of government bursaries and scholarships I was also able to educate my children.

Together with the other women who were weaving, we decided to form a cooperative, an act that later on caught the eye of area government leaders. Pretty soon I was attending government conferences on group leadership, community health and hygiene forums, trainings on agricultural practices, as well as others.

Members of our cooperative also attended weaving training, where we were instructed on numerous things relevant to weaving as an income generating activity. We were taught how to weave by following a guide that included measurements and styles, as well as quality control and marketing.

In 2007, members of our cooperative chose me to be the new chairlady. We have since had two other elections and they have voted me back each time. We’ve come to rely heavily on basket weaving, especially because of the changing climate and the unpredictable rains. And with the growing membership numbers, larger purchase orders means that everyone is guaranteed work.

I wouldn’t have been able to raise and educate my children if I gave up and didn’t believe in myself, especially after the death of my husband. Proceeds from weaving helped educate my children. I am now able to clothe and feed myself and my family from the income from weaving. Sometimes I find that I even have money left over, which I save or invest in my grocery business. In my village, there has been an increased interest in ventures that aid the independence of women, like weaving. In fact, our cooperative membership has been on the rise. It makes me happy when I interact with fellow members of our cooperative and see visible results of basket weaving in their lives – one member is able to purchase medicine for her child, another can afford a new dress, more are able to educate their children and feed and clothe their families.

Our cooperative was also able to purchase a piece of land, upon which we plan to build a community center. Such actions I believe have emboldened other women in this area to get out there, join such ventures and take charge of their lives.

Photo: Shilpi Rani Das started working in a garment factory when she was 12 years old and moved to work at Rana Plaza at 13. She was working on the 8th floor at the time of the factory collapse. She lost an arm and spent the next 2 1/2 years in hospital. She is now at school, plays badminton and supports her family by sending money home. She is starting Open University.

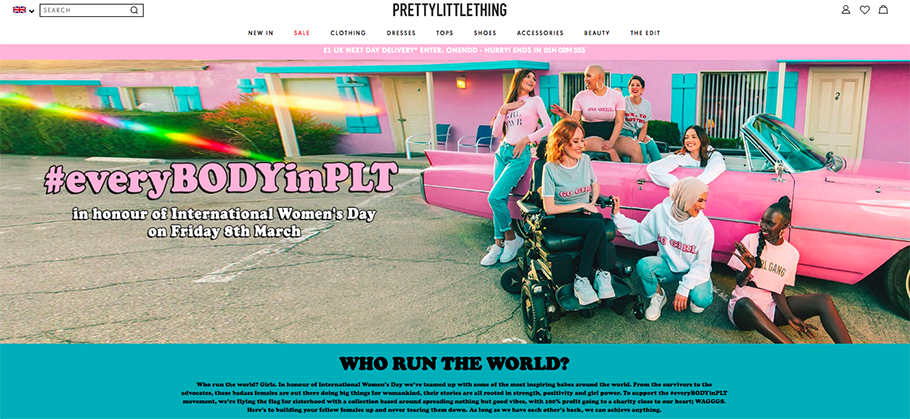

The theme of International Women’s Day 2019 is #BalanceforBetter and asks how we can help forge a more gender-balanced world. Brands and retailers are, predictably, all doing their bit to show support, from Pretty Little Thing’s promotion of their #EveryBodyInPLT movement with T-shirts from £10, with profits going to the charity WAGGGS to Net-a-Porter’s limited edition collection in collaboration with six female designers, with profits going to Women for Women International.

None of the webpages about the T-shirts feature any information about how or where they are made or who made them. About 75 million people work directly in the fashion and textiles industry and about 80% of them are women. Many are subject to exploitation and verbal and physical abuse. They are often working in unsafe conditions, with very little pay.

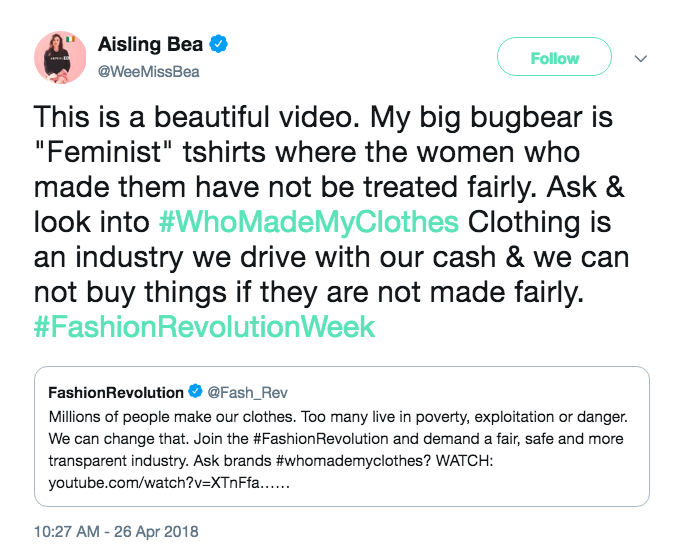

Actress Aisling Bea tweeted during Fashion Revolution Week last year: “My particular bugbear is feminist tees which were not made by women who were paid fairly for their labour. Check your tags and brands.”

Slogan T-shirts with female empowerment messages will be everywhere this week to coincide with International Women’s Day, but the reality is that the fashion industry doesn’t empower the majority of women who work in it. Gender-based inequality remains a problem throughout the industry, from the highest levels of management to the shop floor and the factory floor. We still have a very long way to go until everyone who makes our clothes can live and work with dignity, in healthy conditions and without fear of losing their life.

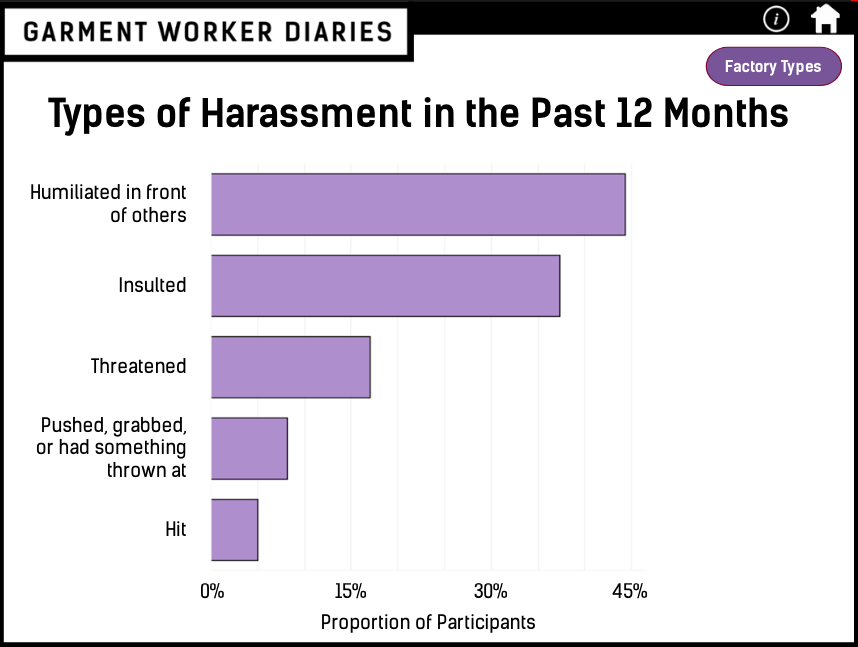

One of the main projects Fashion Revolution worked on in 2017/18 was the Garment Worker Diaries. On-the-ground research partners met with 540 garment workers in India, Cambodia and Bangladesh on a weekly basis for twelve months to learn the intimate details of their lives. 60% reported gender-based discrimination, over 15% reported being threatened and 5% had been hit. When I met with the President of the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association in November 2017, he told me categorically that sexual harassment doesn’t exist in garment factories in Bangladesh. One statistic I found particularly shocking was that 40% of the workers surveyed had seen a fire in their place of work. The women making our clothes are still risking their lives every day for our fashion fix.

In January, The Guardian revealed that Spice Girls T-shirts raising money for Comic Relief’s Gender Justice campaign were being made at a factory in Bangladesh where women earned 35p an hour and claimed to be verbally abused and harassed. Garment production in Bangladesh is still carried out in a very opaque manner and the lack of information about where our clothes and shoes are made and who made them is a huge barrier to changing the fashion industry. This means that gender inequality and human rights abuses and remain rife. If you can’t see it, you can’t fix it, which is why Fashion Revolution urges all brands and retailers to have full supply chain transparency, and we track this through our annual Fashion Transparency Index.

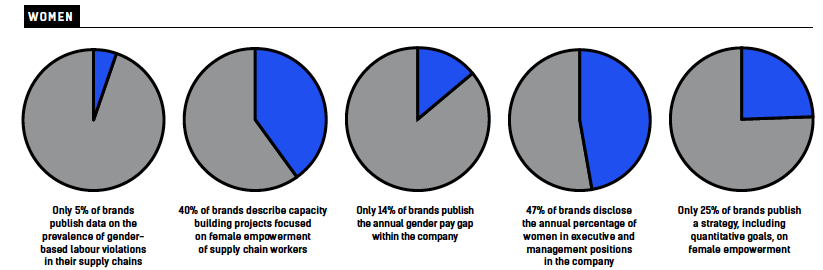

Fashion Revolution’s Fashion Transparency Index 2018 which reviews and ranks 150 major global brands and retailers according to their social and environmental policies, practices and impacts, throws a spotlight on how brands and retailers are tackling gender-based discrimination and violence in supply chains. The report specifically looks at how they are supporting gender equality and promoting female empowerment, both in their own company and in the supply chain.

Whilst, most brands publish policies on discrimination, harassment and abuse, the research show that only 37% of brands are publishing human rights goals. Without reporting on goals and, importantly, annual progress towards these goals, consumers have no way of knowing whether their clothing purchases are really helping to drive improvements for the women who are making their clothes.

Only 40% of brands and retailers reported on capacity building projects in the supply chain that are focused on gender equality or female empowerment, while just 13% publish detailed supplier guidance on issues facing female workers in their Supplier Codes of Conduct. Only 37 out of the 150 brands surveyed report signing up to the Women’s Empowerment Principles, an initiative by the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality, or publishing the company’s overall strategy and quantitative goals to advance women’s empowerment. Meanwhile, just 5% of brands are disclosing any data on the prevalence of gender-based labour violations in supplier facilities, such as sexual harassment and other forms of gender-based violence, or the treatment and firing of pregnant workers.

In the 2019 Fashion Transparency Index, to be published in April, we will be surveying 200 brands and asking the same questions around women’s empowerment. Women’s economic empowerment and closing gender gaps at work is key to realising women’s rights and central to achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, in particular SDG 8 on promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.

According to the BoF McKinsey & Company report The State of Fashion 2019 “Younger generations’ passion for social and environmental causes has reached critical mass, causing brands to become more fundamentally purpose driven to attract both consumers and talent”. As a result, the appearance of the word “feminist” on retailer homepages and newsletters is forecast to increase in frequency sixfold compared to two years ago. Brands are adopting feel-good feminist slogans, yet the rise of real feminism and female empowerment within the industry is a long way off for most women who work in it, from the highest levels of management to the shop floor and the factory floor.

If we really want to see a more gender balanced world, brands and retailers need to do more than sell empowering T-shirts; they need to make sure their policies are put into practice. And not just in the visible places, on fashion shoots or within their company, but at every level of their supply chains. The people making our clothes may not be visible, but every garment they make has a silent #MeToo woven into its seams. At Fashion Revolution, we believe positive change in the fashion industry is possible, and it starts with transparency.