An Australian Modern Slavery Act: what does it mean for the fashion industry?

Laura McManus for Fashion Revolution Australia

It’s 7am in the manufacturing suburb of Savar, on the outskirts of Bangladesh’s capital Dhaka, and 23-year-old Fatema wakes for the day. After working a minimum of 10 hours a day, she completes another three hours of household chores before retiring at midnight, exhausted. In peak production periods she has worked up to a 98-hour work week, all while being verbally assaulted by her manager. On average Fatema earns $0.40AUD an hour and lives in constant financial hardship, resulting in a cycle of loans to cover incidentals such as medicine. While there is no formal worker representation in her factory, Fatema has participated in a six-hour strike when her wages were delayed by almost a week.

Fatema is not unique. She is one of the four million garment workers In Bangladesh’s Ready Made Garment (RMG) sector. Her story is extrapolated from the Garment Worker Diaries, a year-long research project into the economic lives of garment workers in Bangladesh, Cambodia and India. Fatema is not in a situation of modern slavery, however, her precarious financial situation, coupled with low literacy levels and weak rule of law, make her vulnerable to exploitation. Vulnerability and exploitation occur on a continuum, with modern slavery the most egregious human rights violation found in global supply chains, including the garment sector.

The Global Estimates of Modern Slavery tell us that of 40 million people estimated in modern slavery, 16 million people experience forced labour in the private economy. More than half of those are women and more than half are in a situation of debt bondage. While a specific breakdown is not available for the garment sector, 15% of forced labour occurs in manufacturing and 11% in agriculture, including the cotton that may end up your t-shirt. Supply chains are complex and still very much opaque the further down the rabbit hole you go.

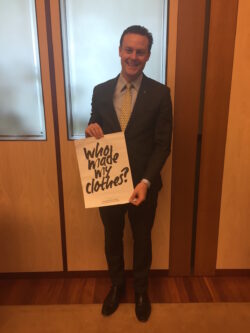

Chris Crewther, Federal Liberal Minister and Chair of the Government’s Inquiry into Establishing an Australian Modern Slavery Act, believes a lack of transparency and hidden subcontracting increases the risk of goods made with modern slavery entering Australia. “When purchasing a shirt from an Australian business,” he explains, “you may see a ‘Made in [country]’ label indicating its source. However, that label is often indicating the location where the shirt was assembled, as opposed to the source point of every aspect of the shirt. Where did the buttons come from? The dyes? The cotton? The risk is that these subcontracted raw material suppliers are more likely to utilise modern slavery, as they do not directly engage with the standards and expectations of the Australian business who is ultimately selling the shirt.”

What, then, is the role of legislation in driving corporate change in an industry that has traditionally sought a ‘race to the bottom’ to produce the cheapest goods? Can legislation in Australia meaningfully impact Fatema’s daily life in Bangladesh?

This year the Federal Government will legislate an Australian Modern Slavery Act including a reporting requirement for business. Building on the UK Modern Slavery Act, we can expect:

- Entities including business, non-for-profit and government, over a certain threshold (likely $100mil) will be required to produce a statement on the steps they are taking to eliminate slavery from business operations and supply chains;

- Companies will need to report on four mandatory criteria including entity structure, modern slavery risks, policies & processes to address risk, and due diligence processes;

- At this stage, no penalties for non-compliance;

- A central and mandatory repository of statements;

- The legislation to be reviewed after three years; and

- The potential for an Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner.

Photo credit: Nicole Wong

Senator Lisa Singh, also a member of Government Inquiry, says turning a blind eye is no longer an option. “The fact is that many of the women and men making our clothes are living in poverty. When the products we purchase are tainted by exploitation, we are all tainted; we are all contributing to that exploitation.” She continues, “The Australian Modern Slavery Act will help businesses take every step they can to put pressure on suppliers and notify authorities, as well as ensuring they are more careful

about checking who their suppliers are and what kind of labour practices they engage in.”

Crewther, looking further ahead, is optimistic the Act will begin a race-to-the-top for businesses. “Those businesses which delay to act or only undertake the minimum will be caught out when compared to those which seize the opportunity to engage with the reporting requirements,” he adds.

Supply chain transparency is at the core of Fashion Revolution. In the five years since the Rana Plaza disaster more than 150 big brands, including those in Australia and New Zealand, have published the factory lists of where their clothes are made. Transparency, alongside good due diligence, helps businesses better understand and mitigate their risks, and enables consumers to make more informed choices. “The conditions of garment workers which led to the Rana Plaza collapse were significant in raising awareness for Australian consumers,” reflects Senator Singh. “I hope more Australians purchase their clothes from manufacturers that treat their workers ethically.”

It is expected that an Australian Modern Slavery Act will create a level playing field or, better yet, a new league table where modern slavery compliance is a minimum standard, and beyond compliance is the goal. It crucial, more than ever to keep asking brands #whomademyclothes? and celebrate those that dare tell us.