By Nathalia Orquera

Few people realize that Los Angeles is the center of the country’s garment manufacturing industry, housing the largest cut and sew apparel base in the U.S, most of whom are immigrant women from Mexico and Central America.

U.S. clothing factories employ about 200,000 people, with the greatest concentration in California. Los Angeles has more than 45,000 cutting and sewing operators alone, while in comparison, the New York City area employs less than 25,000 garment workers.

Garment workers in California face many of the same hurdles that garment workers overseas endure every day, from working in deplorable sweatshops condition, wage theft, abuse, to working an average of 55 hours a week with no overtime pay. Fast fashion is at the root of the many violations plaguing this industry. Cut and sew factories receive orders from large manufacturers often working for big brands, who are willing to produce items for little pay and with unrealistic manufacturer deadlines.

Despite the 1999 landmark Assembly Bill 633 (AB633) that sought to end wage theft in the garment industry, laws and protections continue to be circumvented so that retailers and manufacturers can avoid liability.

“This is a monumental occasion for the fashion industry and garment workers statewide because we haven’t seen any major reform to protect garment workers in over 20 years,” says Nicholas Brown, director of policy for Fashion Revolution USA. “This bill comes at a particularly crucial time, as many of these workers are facing the additional burden of exposure to COVID-19. California has the power to set the standard for safe, humane, and ethical labor practices in the garment industry that has the opportunity to be replicated well outside of Los Angeles.”

The new Garment Worker Protection Act (Senate Bill 62) co-authored by Senator Maria Elena Durazo and sponsored by Garment Worker Center, is a California bill that would improve working conditions in America’s largest garment industry by ensuring that brands share in the responsibility for garment worker pay under the law. SB62 would strengthen protections for garment workers in three essential ways by:

- Eliminating the use of the piece-rate system of pay, instead of ensuring that the legal hourly wage becomes the floor, not the ceiling, of wages paid to garment workers. The bill allows for incentive-based bonuses tied to productivity on top of the legal wage.

- Establishing multilateral accountability among brands and manufacturers for wage violations.

- Strengthening the authority of the Labor Commissioner’s investigation bureau to investigate and cite violations up the supply chain.

The piece-rate system compensates garment workers for each piece of clothing produced, as opposed to a set hourly wage. According to wage theft claims, some garment workers in L.A. are earning as little as $2.68 an hour through the piece rate system of pay, far below the LA minimum wage of $15 per hour for workplaces with 26 or more employees. According to the Garment Worker Center, the Covid-19 pandemic has only worsened their working conditions, where workers are often not given the time to wash their hands, factories are not sanitized between shifts or users, and bathrooms lack hand soap.

The California legislative cycle involves four different rounds of voting throughout the year. SB62 will start in a Senate subcommittee, get passed to the Senate, then the Assembly and then finally to the governor’s desk in the fall of 2021. On Monday, March 22, 2021, SB62 passed the CA Labor Subcommittee, which is the first vote in the process of getting this bill into law as it moves to the Senate Floor. On Tuesday, April 6, 2021, the bill passed through the Senate Judiciary Committee–the second of three committee hearings in the Senate, and another hopeful sign for the future of SB62. And on Monday, May 24, 2021, the bill passed through the full California Senate.

After the passing of SB62 in the Senate, the bill moved to the CA State Assembly to go through the committee process all over again in the second house. The Assembly made several amendments to SB62’s language, which had originally expanded upstream liability to retailers and brands.

On September 8, 2021, SB62 (with new amendments) passed the full CA State Assembly, only a few days shy of the September 10, 2021 deadline- the final day for any bill to be passed and the end of the 2021 legislative session.

However, this milestone and momentous victory of passing both houses was quickly eclipsed by last-minute political maneuvering. Despite receiving the backing of CA legislators, the bill was purposefully held and tied up in the Assembly, even after receiving a successful vote. SB62 needed to return to the Senate for a final approval of the amendments but had not been sent out of the Assembly.

On the last day of the legislative session, garment workers, fair wage and fashion advocates across the state, and organizations like the Garment Worker Center, Remake, PayUp, and FRUSA, began a late social media campaign and pressure to pass SB62. At the final hour, SB62 was finally resent to the Senate for final approval of the amendments and passed the full CA State Legislature. On September 17, 2021, SB62 was sent to CA Governor Newsom’s desk for the final step to become law, where it currently still awaits his signature or veto.

The fight to pass the Garment Worker Protection Act, SB62, is not over! Though SB62 passed the CA State Legislature, its fate currently rests with CA Governor Newsom, who has until October 10th to veto or sign bill.

Getting SB62 this far has come with many hurdles and truly has been a process decades in the making (with previous bills failing earlier in the past).

SB62 is a landmark legislation that has the potential to create industry-wide change by putting an end to the piece-rate system, paying fairer wages, and establishing basic workplace protections for CA garment workers.

To pass SB62, act now and contact Governor Newsom!

- Call Governor Newsom at (916) 445-2841.

- Urge him to stand up for garment workers and demonstrate his commitment to the minimum wage, fair working conditions, and corporate accountability by signing SB62 into law.

SB62 will become a historic step toward ending the modern sweatshop regime and will also help re-establish the United States as an epicenter of ethical manufacturing. As consumers we can help by holding brands accountable, understanding issues impacting garment workers’ rights, and sharing this information.

Join Fashion Revolution USA, Remake, and the Garment Worker Center in supporting California’s garment workers! Whether you live in the state of California or not, including residents of other nations, we encourage you to sign this petition and to share information about the importance of this bill with your friends, family and followers. And, watch “State of Play: Garment Worker Protections in the United States,” where we learned more of these key issues with Sen. María Elena Durazo, representing California’s Senate District 24; Dr. Elizabeth Segran, senior staff writer at Fast Company; Ayesha Barenblat, founder and CEO of Remake; Marissa Nuncio, director of Garment Worker Center; and Sarah Ditty, global policy director at Fashion Revolution.

Information for this article courtesy of Garment Worker Center and Remake.

Intro by William Persson

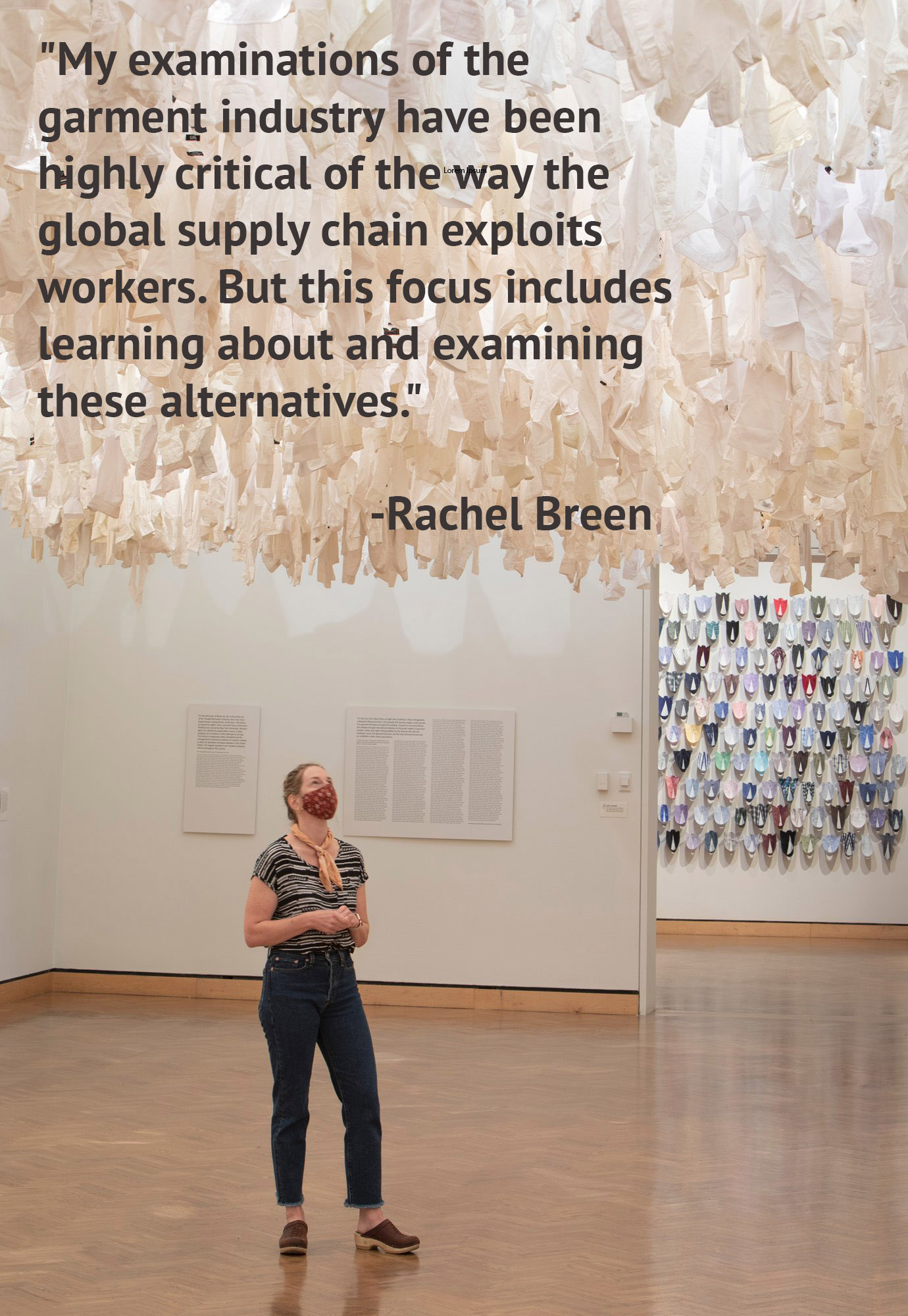

Our Fashion Revolution USA Director of Operations and Community Ashleyn Przedwiecki interviewed Rachel Breen about her work “The Labor We Wear,” which highlights the relationships between the garment industry, workers in the supply chain, and fashion consumers. They address what inspired the pieces and how incidents like the Rana Plaza Factory Collapse have influenced her drive to tell the stories of garment workers. This Q&A has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

ASHLEYN P.: I watched your talk with the Minneapolis Institute of Art and I was so drawn to how you incorporate ethics and social justice into your artistic approach. Can you talk more about your background and what led you to create your current show, The Labor We Wear?

RACHEL B: For years, long before I thought much about garment workers and before the Rana Plaza Factory Collapse, I used my sewing machine as a drawing tool. I still think of my sewing machine as my third arm. When the Rana Plaza Factory did happen, I remember thinking about what it would feel like to be in my 4th-floor studio in NE Minneapolis, sitting at my sewing machine, and have the floor give way beneath me. My horror over the Rana Plaza Factory Collapse and the lives lost and thousands injured gave rise to a deep desire to respond and speak out.

The idea for this exhibition also came from a recognition that the ways garment workers are exploited are not new -that garment workers have been mistreated since the birth of the industrial revolution. I realized this in part because I connected this disaster to a disaster I grew up knowing about: the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire that took place in 1911 in New York City. One hundred forty-six mostly Jewish and Italian immigrants died in this fire, one of the worst worker disasters in the US at that time. I wanted to make work that showed that Americans are not removed from the exploitation of garment workers -but are linked historically as well as through the clothes that we wear.

A.P.: Can you share more about your experience in Bangladesh after the Rana Plaza factory collapse?

R.B.: My experience in Bangladesh was very powerful. I’ll share a few things that were especially important lessons for me. One, is that women suffer daily physical and verbal harassment, are frequently not paid what they are owed and daily work in factories that are extremely unsafe -to a degree that I had not realized. Death and injury happen all the time and we just don’t hear about it. The need for and importance of unions in Bangladesh came into clear focus for me. The labor union movement in Bangladesh is quite nascent but is more important than ever because it is the only collective voice for these women and the only clear way to empower them to address unfair wages and working conditions.

I traveled to Bangladesh with my friend and writer Alison Morse. Both of us are Jewish and were making this connection between the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire and the Rana Plaza Factories collapse. We shared this story with many of the women we met when we would explain why we were there. Many of them told us we should meet with the Tazreen Factory fire survivors because that tragedy was even more familiar to the Triangle Shirtwaist fire so we did. Learning about this other tragedy it dawned on me that there were probably so many disasters that I did not know about. We did interview many survivors of the Tazreen Factory fire and it was just as heartbreaking as speaking to the survivors of the Rana Plaza Factory Collapse. I was constantly surprised by the willingness of women to share their stories. Women want to be heard.

A.P.: This exhibition is one of many you’ve worked on that focuses on the untold stories of garment workers and spotlighting the people behind our clothing. What was the inspiration behind this? And how do you turn an idea into an art piece or a full exhibition?

R.B.: The more I have learned about the global garment industry the more I have felt outraged and deeply concerned about the treatment of workers, and the ramifications of overproduction on the part of corporate brands, overconsumption by the American public, the waste all this causes, and how it impacts our planet. It is absolutely horrifying, and I hope that my work can contribute to behavior changes, but more importantly, lead to policy changes that address this industry.

As an artist, I am very curious and interested in how materials convey meaning. Once I began to work on this issue I thought a lot about the materials that would help tell the many aspects of the story of Rana Plaza, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, the daily labor of garment workers, and our connection, as consumers to these stories. I spend a lot of time in my studio playing with materials: taking things apart, arranging them, rearranging them until they start to speak the way I want them to. This focus on exploring materials in my work and the public response to it has inspired my continued journey of making work on this subject.

A.P.:What are you hoping people will come away with after exploring one of your exhibitions?

R.B.: I hope that people feel moved in some way. I hope the work encourages people to reflect on the themes in my work and that it provides them with a larger lens through which to look at the world and their (our) things.

A.P.: Did you imagine your installation to become as popular and moving as it has been to so many people?

R.B.: That is a great question! No, I imagined and hoped but I did not know what an impact the work would have. With a project this large, you don’t really know what it will look like until it’s finished and installed. I was so nervous! I spent months working on it and finally when it was up I couldn’t believe how powerful it was — I was so happy and also sorrowful — you can’t look at the work and not feel both emotions.

A.P.: How does the sewing machine play a role in your work as an artist?

R.B.: I am interested in the creative possibilities of the sewing machine. I use it to draw, create installations and initiate socially engaged public projects. I am a maker, yet much of my work involves the opposite: I “unmake” things and “dismantle” ways of seeing and believing. I am interested in the sewing machine as a deeply symbolic and also (im)practical object.

A.P.: You use art as a tool for social change, can you talk more about how you see the relationship between art and social justice movements?

R.B.: I think that art can help the public look at a problem or a situation with new perspectives and in a way that is empowering. Successful community organizing requires building power, and I believe building power begins with having new insights and believing that change is possible.

A.P.: Do you have any advice for young designers, artists, or leaders as they challenge/confront the deeply ingrained issues within our current fashion industry?

R.B.: Work from a place of community. That means building community so that you can collectively challenge, confront, advocate and build towards your vision. Have a vision of the change you want to see, otherwise, you won’t have a sense of direction. Engage, be open to being wrong and be brave!

A.P.: What is next for you as you pursue a continuation of this body of work? How do you hope it might unfold and drive change?

R.B.: My examinations of the garment industry have been highly critical of the way the global supply chain exploits workers. But this focus includes learning about and examining these alternatives. I’m currently envisioning the development of visual language that explores alternative economic models to capitalism.

Rachel Breen received her MFA from the University of Minnesota and is involved in creating her pieces using non-traditional materials and exhibition spaces that aim to inspire community engagement in social justice initiatives. In “The Labor We Wear,” she utilizes clothing to hold consumers accountable for the life cycle of garments, from unsafe working conditions to textile waste. The work makes these relationships visible in order to break the cycle.

The Corona Virus Disease 2019 (CoViD-19) pandemic has infected 3 million people and claimed 230 thousand lives worldwide. The lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) used by healthcare workers is one the challenges they face. The World Health Organization (WHO) has asked the different countries to manufacture more PPEs. In the Philippines healthcare workers are at a high risk. Most private hospitals use 10 to 15 PPE suits for one CoViD-19 patient in a week. While the Philippine General Hospital use 3 PPE suits also in a week. The PPEs can only be used for i a limited number of times.

People try to help by raising funds for more PPEs but manufacturers cannot cope up with the demand. The fashion community stepped up to help with the situation. These include the textile and garment workers, designers, artisans, and ordinary citizens who can sew PPE. The drawback is that many of them are not near medically standards and end up use by someone else.

Volunteers sewing thousands of PPE suits, Photo courtesy of Abbey Balagbagan

Three students from Institute of Creative Entrepreneurship – Fashion and Design (ICE- FAD) have made PPEs based on the feedback they get from the healthcare workers to whom they donate it. Leilina Kate Yalung has made 300 washable face masks, Abbey Balagbagan has produce 20,000 face masks and 10,000 a two piece PPE suits since March 30 (as of April 21) will continue to do so until needed, and Erjohn dela Serna has made 982 pieces where he targets to create around 1,500. They have donated them to different barangays, Pasig City General Hospital, Child’s Hope Children’s Hospital, Cainta, Tarlac, Angeles, Pangasinan, Bacolod, Bulacan, and Navotas.

Erjohn dela Serna PPE suit designs

Kyra M. Mata has also donated 335 isolation (or hazmat) suits and 500 gowns. That went to the Southern Philippine Medical Center and other parts of Davao City with a project with Wear Forward called “Wear Together”. These hand-sewn suits are made from taffeta SBL (Silver Black Lining) the same material used for umbrellas. The patterns are cut to make sure they sew less and with a covering over the fly. They adjust the tension and make shorter stitches when sewing. Then do the water submersion test to check if they are air-tight. They sought advice from an Infectious Disease Specialist and help from Kendi Maristela, who teaches in the University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman College of Home Economics Clothing Tech Course, to make sure it is close to the medical-grade standard, which is a big challenge. She started the PPE design that is approved by the Department of Health (DOH). Another challenge supplies. They can only make as much as long the materials are available. They only use available stocks and rely on donations because they already spent enough money on their own.

The Manila Protective Gear Sewing Club was organized for the sole purpose of making these PPEs suits. They donate them to the Office of the Vice President (OVP) who has started aiding healthcare workers since the shortage through donation, collaboration, and calling for volunteers. It is through the OVP that they distribute the PPEs so there will be less hassle. According to Cynthia Diaz and Mich Dulce, of Manila Protective Gear Sewing Club, that there are no medical-grade fabrics or medical-grade production companies in the Philippines. In order to achieve the medical-grade standard, they consider every detail and the construction of the design that is reviewed and tested by a medical organization such as a hospital or an independent medical consultant. The design they have has been medically approved by the doctors behind the Open Source Covid19 Medical Supplies based in Berkeley, California.

Healthcare workers trying out the donated PPE suits, Photo courtesy of Dr. Maria Almira Kiat

It is most rewarding to receive feedback from the different recipients of their donated PPE. Healthcare workers are overwhelmed that there are people like them willing to help in these times of crisis despite the restrictions imposed by the quarantine. They are also excited because of the different colors and designs of the PPE suit that is unusual to see. It also helps patients to recognize them which everyone is so grateful for. The advantage of these PPEs is that they are reusable and washable. According to Dr. Winston Pascual, who works in a public hospital with CoViD-19 patients, said that they are reusable and washable. They are cleaned by using bleach solution and bathe under the sun. Dr. Maria Almira Kiat, of Bataan General Hospital and Medical Center, said that as much as possible they autoclave besides washing. There are other areas where the healthcare workers are hesitant to autoclave them. The recipients of Kyra told her that even they have heat tested their PPE suits. Autoclave is one of the ways they can disinfect them properly, especially if used in direct contact with a CoViD-19 patient. Dr. Maria Almira said that they already have healthcare workers that got infected. That is why they categorize these PPE suits into two types A and B. The type A are inside wards that are in full gear or complete overall suits where they attend positive and suspected CoViD-19 patients. The other suits are considered type B where they use it outside the ward. These PPE suits are more comfortable compared to the ones procured from China by the DOH. Other countries have rejected these PPEs from China because they are defective.

Donated DIY PPE suits are washed and sun dried, Photo courtesy of Kyra Mata

Despite the quarantine restriction people can still find a way to help in this time of crisis. It is people from the fashion community, from textile workers to designers, that can care for the needs of heroes who are the healthcare workers in the front line.

I like to end with a quote

“Fashion is the armor to survive the reality of everyday life.”

– Bill Cunningham.

WHY SHOULD BRANDS PUBLISH SUPPLIER LISTS?

Publicly disclosed supplier lists are helping trade unions and workers rights organisations to address and fix problems which workers are facing in the factories that supply major brands and retailers. This sort of transparency makes it easier for the relevant parties to understand what went wrong, who is responsible and how to fix it. It also helps consumers better understand #whomademyclothes.

“Knowing the names of major buyers from factories gives workers and their unions a stronger leverage, crucial for a timely solution when resolving conflicts, whether it be refusal to recognise the union, or unlawful sackings for demanding their rights. It also provides the possibility to create a link from the worker back to the customer and possibly media to bring attention to their issues.” says Jenny Holdcroft, the Assistant General Secretary of IndustriALL Global Union

HAVE WE SEEN AN INCREASE IN BRANDS PUBLISHING SUPPLIER LISTS?

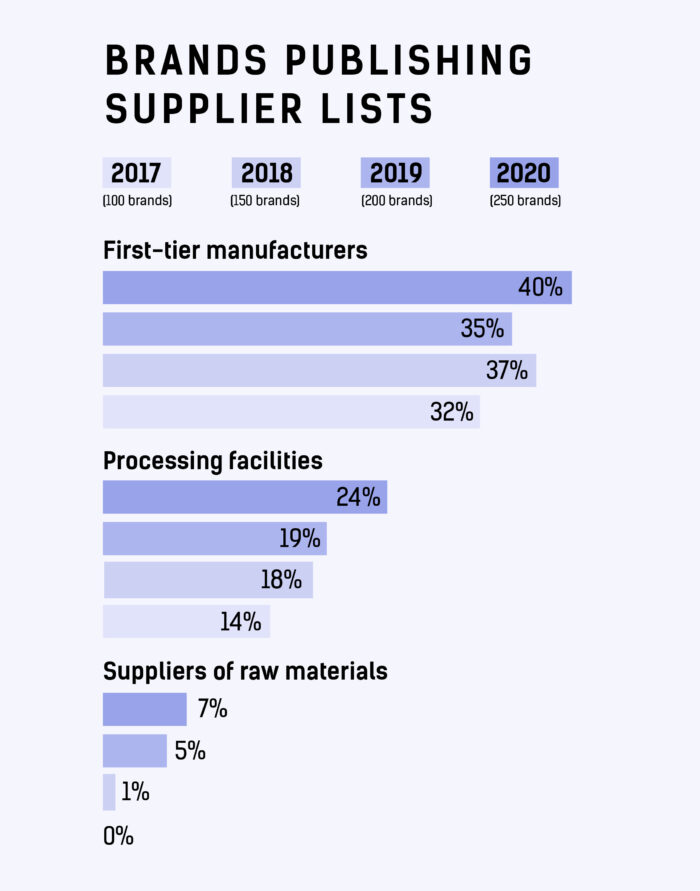

Since we began the Fashion Transparency Index in 2016, we have seen a significant increase in the number of brands publishing their first tier, processing and raw materials suppliers. In our 2020 edition of the Fashion Transparency Index, 101 out of 250 brands (40%) are publishing their first-tier manufacturers, up from 35% in 2019. These are the facilities that do the cutting, sewing and finishing of garments in the final stages of production.

60 out of 250 brands (24%) are publishing some of their processing facilities, up from 19% in 2019. These are the sorts of facilities that do ginning and spinning of yarn, knitting and weaving of fabrics, dyeing and wet processing, leather tanneries, embroidering and embellishing, fabric finishing, dyeing and printing and laundering.

And, 18 out of 250 brands (7%) are publishing some of their raw material suppliers, up from 5% in 2019. These suppliers are those that provide brands and their manufacturers further down the chain with raw materials such as cotton, wool, viscose, hides, rubber and metals.

HOW MANY BRANDS ARE NOW PUBLISHING SUPPLIER LISTS?

We have looked at large brands (over £36 million annual turnover) beyond the Fashion Transparency Index to count the number that are publishing lists of their suppliers. Below, you will find a list of over 200 brands that are publishing their first-tier manufacturers, 60 brands that are publishing their processing facilities and 21 brands that are publishing their raw material suppliers.

We are always pushing brands to provide more information about the people who make their clothes, and you can encourage them to do so too. Always ask the brands you buy #WhoMadeMyClothes. You can do this by tagging your favourite brands on social media and using this hashtag, or you can use our automated email tool to get in touch with them directly.

Brands who publish first-tier supplier lists

First-tier/ Tier One/ manufacturing suppliers are those which have a direct relationship with buyer e.g. production units, Cut Make Trim (CMT) facilities, garment sewing, garment finishing, full package production and packaging and storage.

& Other Stories (H&M group)

Abercrombie & Fitch

Adidas

ALDI-Nord

ALDI SOUTH

Amazon

Ann Taylor

Anthropologie (URBN)

ARROW (PVH)

ASICS

Aldi North

ASOS

Athleta (GAP Inc.)

Autograph (Speciality Fashion Group)

Banana Republic (GAP Inc.)

Berghaus (Pentland Brands)

Berlei (Hanes)

BESTSELLER

BigW (Woolsworth Group)

Black Pepper (PAS Group)

Boden

Bon Prix

Bonds (Hanes)

Boxfresh (Pentland Brands)

Brand Collective

Brooks Sports

Burton (Arcadia)

C&A

Calvin Klein (PVH)

Champion (Hanes)

Cheap Monday (H&M group)

City Chic (Speciality Fashion Group)

Clarks

Cole’s (Wesfarmers Group)

Columbia Sportswear Co.

Converse (NIKE, Inc)

Cos (H&M group)

Cotton:On

Crossroads (Speciality Fashion Group)

Curvation (Fruit of the Loom, Inc.)

David Jones

Debenhams

Designworks (PAS Group)

Disney

Dorothy Perkins (Arcadia)

Dressmann (Varner)

Eagle Creek (VF Corporation)

Eastpak (VF Corporation)

Eileen Fisher

El Corte Inglés

Ellesse (Pentland Brands)

Esprit

Evans (Arcadia)

Factorie (Cotton On Group)

Fanatics

Fjällräven

Forever New

Free People (URBN)

Fruit of the Loom

G-Star

Galeria Inno (HBC)

Galeria Kaufhof (HBC)

Gap

George at Asda (Walmart)

Gildan

H&M

Hanes

Helly Hansen

HEMA

Hermès

Holeproof Explorer (Hanes)

Hollister Co. (Abercrombie and Fitch Co.)

Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC)

HUGO BOSS

Hurley (NIKE, Inc)

Intermix (GAP Inc.)

IZOD (PVH)

JACK&JONES (BESTSELLER)

Jack Wolfskin

Jacqueline de Yong (BESTSELLER)

JAG (APG & Co)

Jansport (VF Corporation)

Jeanswest

JETS Swimwear (PAS Group)

Jockey (Hanes)

John Lewis

Joe Fresh (Loblaw Companies Limited)

Jordan (NIKE, Inc)

Junarose (BESTSELLER)

KangaROOS (Pentland Brands)

Kathmandu

Katies (Speciality Fashion Group)

Kaufland

Kayser (Hanes)

Kipling (VF Corporation)

Kmart Australia (Wesfarmers Group)

Lacoste

Lee (VF Corporation)

Levi Strauss & Co.

Lidl

Lindex

Littlewoods (Shop Direct)

Loblaw

Loft (Ascena)

Lord & Taylor (HBC)

lucy (VF Corporation)

Lululemon

Majestic (VF Corporation)

Mamalicious (BESTSELLER)

Mammut

Marco Polo (PAS Group)

Marimekko

Marks & Spencer

Matalan

MEC

Millers (Speciality Fashion Group)

Missguided

Miss Selfridge (Arcadia)

Mizuno

Monki (H&M group)

Monsoon

Morrisons (Nutmeg)

Name It (BESTSELLER)

Napapijiri (VF Corporation)

Nautica (VF Corporation)

New Balance

New Look

Next

Nike

Noisy May (BESTSELLER)

Nudie Jeans

Old Navy (GAP Inc.)

Only (BESTSELLER)

Only & Sons (BESTSELLER)

Outerknown (Kering Group)

Outfit (Arcadia)

OVS

Patagonia

Pieces (BESTSELLER)

Pimkie

Playtex (Hanes)

Primark

Prisma (S Group)

Puma

R.M Williams

Razzamatazz (Hanes)

Red or Dead (Pentland Brands)

Reebok (Adidas Group)

Reef (VF Corporation)

REI Co-op

Review (PAS Group)

Rider’s by Lee (VF Corporation)

Rio (Hanes)

River Island

Rivers (Speciality Fashion Group)

Rock & Republic (VF Corporation)

rubi (Cotton On Group)

Russell Athletic (Fruit of the Loom, Inc.)

Sainsbury’s – Tu Clothing

Saba (APG & Co.)

Sak’s Fifth Avenue (HBC)

Selected (BESTSELLER)

Sheer Relief (Hanes)

Sisley (Benetton Group)

Smartwool (VF Corporation)

SPALDING (Fruit of the Loom, Inc.)

Speedo (Pentland Brands)

Sportscraft (APG & Co.)

Supré (Cotton On Group)

Target

Target Australia (Wesfarmers Group)

Tchibo

Ted Baker

Tesco

The North Face (VF Corporation)

The Warehouse

Timberland (VF Corporation)

Tod’s

Tommy Hilfiger (PVH)

Tom Tailor

Topman (Arcadia)

Topshop (Arcadia)

Under Armour

Uniqlo (Fast Retailing)

United Colours of Benetton (Benetton Group)

Urban Outfitters (URBN)

Van Heusen (PVH)

Vanity Fair Lingerie (Fruit of the Loom, Inc.)

Vans (VF Corporation)

Vassarette (Hanes)

Vero Moda (BESTSELLER)

Very (Shop Direct)

Victoria’s Secret (L Brands)

Vila Clothes (BESTSELLER)

Voodoo (Hanes)

Wallis (Arcadia)

Warner’s (PVH)

Weekday (H&M group)

White Runway (PAS Group)

Wrangler (VF Corporation)

Yarra Trail (PAS Group)

Y.A.S. (BESTSELLER)

Zalando

Zeeman

Total: 204

Brands who publish processing facilities list

Processing facilities (often referred to as facilities beyond tier 1) are involved in the production of clothing whose activities could involve ginning and spinning, knitting, weaving, dyeing and wet processing, tanneries, embroidering, printing, fabric finishing, dye-houses and laundries.

Adidas

Anthropologie (URBN)

ASICS

ASOS

Banana Republic (GAP Inc.)

Bon Prix

Burton (Arcadia)

C&A

Calvin Klein (PVH)

Champion (Hanes)

Clarks

Converse (NIKE, Inc)

Debenhams

Disney

Dressmann (Varner)

Eileen Fisher

Ermenegildo Zegna

Esprit

Free People (URBN)

Gap

Gildan

G-Star RAW

H&M

Hanes

Helly Hansen

HEMA

Hermès

Jack Wolfskin

Jordan (NIKE, Inc)

Kaufland

Levi Strauss & Co.

Lindex

Lululemon

Monsoon

New Balance

New Look

Nike (Nike, Inc.)

Nudie Jeans

Old Navy (GAP Inc.)

Patagonia

Puma

Reebok (Adidas Group)

Russell Athletic (Fruit of the Loom, Inc.)

Sainsbury’s – Tu Clothing

Target

Tchibo

Tesco

The North Face (VF Corporation)

The Warehouse

Timberland (VF Corporation)

Tommy Hilfiger (PVH)

Topman (Arcadia)

Topshop (Arcadia)

Uniqlo (Fast Retailing)

United Colours of Benetton (Benetton Group)

Urban Outfitters (URBN)

Van Heusen (PVH)

Vans (VF Corporation)

Warner’s (PVH)

Wrangler (VF Corporation)

Total: 60

Brands who publish raw materials supplier list

Raw material suppliers are those which provide the commodity for the production of clothing e.g. cotton, wool, viscose or polyester.

ASOS

Balenciaga (Kering)

Bottega Veneta (Kering)

C&A

Eileen Fisher

Ermenegildo Zegna

Esprit

Gucci (Kering)

H&M Group

Lululemon

Marks & Spencer

Morrisons (Nutmeg)

Nudie Jeans

Patagonia

SAINT LAURENT (Kering)

Tesco

The North Face (VF Corporation)

Timberland (VF Corporation)

United Colours of Benetton (Benetton Group)

Vans (VF Corporation)

Wrangler (VF Corporation)

Total: 21

Please note: We are not endorsing the brands included in this list; this is not a ‘seal of approval.’ While publishing supplier lists is a necessary step towards greater transparency and improved conditions in fashion supply chains, it does not guarantee ethical business practices. However, we hope you find this list informative and continue to ask brands #whomademyclothes.

This list is not exhaustive and only accurate as of April 2020; if you are aware of other large brands (over £36 million annual turnover) that are publishing their suppliers, please let our Policy and Research team know at transparency@

In Autumn 2018 the Environmental Audit Committee wrote to sixteen leading UK fashion retailers, among them M&S, ASOS and Boohoo, asking what they are doing to reduce the environmental and social impact of the clothes and shoes they sell. Today they released their Interim Report on the Sustainability of the Fashion Industry.

Fashion Revolution welcomes the UK Environmental Audit Committee’s findings of their inquiry into the sustainability of the fashion industry. We too want to see a thriving fashion industry in the UK that employs people, inspires creativity and contributes to sustainable livelihoods in the UK and around the world. We agree with the Environmental Audit Committee’s conclusion that the global fashion industry is exploitative and environmentally damaging and that brands and retailers have an obligation to address the fundamental business model.

This report states “We believe that there is scope for retailers to do much more to tackle labour market and environmental sustainability issues. We are disappointed that so few retailers are showing leadership through engagement with industry initiatives.”

Fashion Revolution believes that fashion brands and retailers should sign up to pledges and multi-stakeholder initiatives which are working towards improving workers’ rights, paying a living wage and striving towards a closed loop system. They should also use our Transparency Index as a tool to disclose more about their social and environmental policies, practices and impact both within their companies and throughout their supply chain.

The Committee believes that “The fashion industry’s current business model is clearly unsustainable, especially with a growing middle-class population and rising levels of consumption across the globe. We are disappointed that few high street and online fashion retailers are taking significant steps to improve their environmental sustainability”. Brands are criticised for inadequate sustainability actions and initiatives. The report concludes that recycling waste and complying with the Government’s Carbon Reduction Commitment is not sufficient to offset the environmental damage caused by the fashion industry.

We believe that the fashion industry in the United Kingdom and globally needs far reaching systemic change in order to tackle poverty, inequality and environmental degradation and greater transparency is the first crucial step towards solving its human rights and environmental crises. Our Fashion Transparency Index research has shown that some major brands and retailers are making significant efforts to tackle these issues in their companies and across their supply chains, whilst at the same time far too many large brands and retailers are turning a blind eye. Increased transparency means issues along the supply chain can be identified, addressed and remedied much faster. Greater transparency also means best practice examples, positive stories and effective innovations can be more easily highlighted, shared and potentially scaled or replicated elsewhere.

In an Ipsos MORI survey of 5,000 people across the five largest EU markets published by Fashion Revolution in November, consumers told us they want to know more about the social and environmental impacts of their garments when shopping for clothes and they expect fashion brands and governments to be doing more to address these issues. 77% strongly/somewhat agree that fashion brands should be required by law to respect the human rights of everybody involved in making their products, 75% strongly/somewhat agree that fashion brands should be required by law to protect the environment at every stage of making their products. The majority of people surveyed believed governments should be responsible for holding fashion brands to account for disclosing information about the way their products are made, what suppliers they are working with and how they’re applying socially and environmentally responsible practices in their supply chains.

It is clear that greater government intervention will be necessary if companies are to be held to account for the impacts of their practices on people’s lives and the environment. We want the U.K. Government to pass mandatory due diligence laws, building upon the recent regulatory examples in France and Switzerland. Ultimately, if the UK Government is serious about improving human rights, social impacts and environmental sustainability in the fashion industry, then it must rewrite the rules of the economy so that shareholder profit is no longer prioritised above the protection of our ecosystems and the health and wellbeing of our communities.

The Environmental Audit Committee is launching an inquiry into the sustainability of the fashion industry.

The Committee will investigate the social and environmental impact of disposable ‘fast fashion’ and the wider clothing industry. The inquiry will examine the carbon, resource use and water footprint of clothing throughout its lifecycle. It will look at how clothes can be recycled, and waste and pollution reduced.

Mary Creagh MP, Chair of the Environmental Audit Committee, said:

“Fashion shouldn’t cost the earth. But the way we design, make and discard clothes has a huge environmental impact. Producing clothes requires toxic chemicals and produces climate-changing emissions. Every time we put on a wash, thousands of plastic fibres wash down the drain and into the oceans. We don’t know where or how to recycle end of life clothing.

“Our inquiry will look at how the fashion industry can remodel itself to be both thriving and sustainable.”

The growth of the fashion industry

According to a 2015 report from the British Fashion Council, the UK fashion industry contributed £28.1 billion to national GDP, compared with £21 billion in 2009.[1] The globalised market for fashion manufacturing has facilitated a “fast fashion” phenomenon; cheap clothing, with quick turnover that encourages repurchasing.

Environmental impact of clothing production

Clothing production consumes resources and contributes to climate change. The raw materials used to manufacture clothes require land and water, or extraction of fossil fuels. Clothing production involves processes which require water and energy and use chemical dyes, finishes and coatings – some of which are toxic. Carbon dioxide is emitted throughout the clothing supply chain. In 2017 a report by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation on ‘redesigning fashion’s future’ found that if the global fashion industry continues on its current growth path, it could use more than a quarter of the world’s annual carbon budget by 2050.

Environmental impact of purchase, use and disposal

Synthetic fibres used in some clothing can result in ocean pollution. Research has found that plastic microfibres in clothing are released when they are washed, and enter rivers, the ocean and the food chain.

Sustainability issues also arise when clothing is no longer wanted. A report by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation found that the growth of clothes production is linked to a decline in the number of times a garment is worn. Clothes disposed of in household recycling and sent to landfill instead of charity shops have an environmental impact, such as contributing to methane emissions. Charities have complained that second hand clothes can be exported and dumped on overseas markets. The UK Government has a commitment to ‘Sustainable Production and Consumption’ under UN Sustainable Development Goal 12.

Manufacturing in the UK

In recent years there has been a renewed interest in clothing that has been made in Britain. However there are concerns that the need for quick turn-around in the supply chain to facilitate the demand for “fast fashion” has led to poor working conditions in UK garment factories.

The Committee will also examine the sustainability of garment production in relation to the UK’s social and environmental commitments under the UN Sustainable Development Goals. The UK Government has a commitment to ensuring ‘Decent work and economic growth’ by protecting labour rights and promoting safe and secure working environments for all workers under UN Sustainable Development Goal 8.

Terms of Reference

The Committee invites submissions on some or all of the following points by 5 pm on Monday, 3rd September 2018.

Environmental impact of the fashion industry

- Have UK clothing purchasing habits changed in recent years?

- What is the environmental impact of the fashion supply chain? How has this changed over time?

- What incentives have led to the rise of “fast fashion” in the UK and what incentives could be put in place to make fashion more sustainable?

- Is “fast fashion” unsustainable?

- What industry initiatives exist to minimise the environmental impact of the fashion industry?

- How could the carbon emissions and water demand from the fashion industry be reduced?

Waste from fashion

- What typically happens to unwanted and unwearable clothing in the UK? How can this clothing be managed in a more environmentally friendly way?

- How much unwanted clothing is landfilled or incinerated in the UK each year?

- Does labelling inform consumers about how to donate or recycle clothing to minimise environmental impact, including what to do with damaged clothing?

- What actions have been taken by the fashion industry, the Government and local authorities to increase reuse and recycling of clothing?

- How could consumers be encouraged to buy fewer clothes, reuse clothes and think about how best to dispose of clothes when they are no longer wanted?

Sustainable Garment Manufacturing in the UK

- How has the domestic clothing manufacturing industry changed over time? How is it set to develop in the future?

- How are Government and trade envoys ensuring they meet their commitments under SDG 8 to “protect workers’ rights” and “ensure safe working environments” within the garment manufacturing industry? What more could they do? Are there any industry standards or certifications in place to guarantee sustainable manufacturing of clothing to consumers?

Deadline for submissions

Written evidence should be submitted through the inquiry page by 5 pm on Monday, 3rd September 2018. The word limit is 3,000 words. Later submissions will be accepted, but may be too late to inform the first oral evidence hearing. Please send written submissions using the form on the inquiry page.

Diversity

The Committee values diversity and seek to ensure this where possible. We encourage members of underrepresented groups to submit written evidence. We aim to have diverse panels of Select Committee witnesses and ask organisations to bear this in mind if asked to appear.

Further information

- Guidance: written submissions (including information on data protection)

- About Parliament: Select committees

- Visiting Parliament: Watch committees

Membership of the Committee:

http://www.parliament.uk/business/

committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/environmental-audit-committee/membership/

Media Information: Sean Kinsey kinseys@parliament.uk/ 07917 488791

Specific Committee Information: eacom@parliament.uk/ 020 7219 6150

Committee news and reports, Bills, Library research material and much more can be found at www.parliament.uk. All proceedings can be viewed live and on-demand at www.parliamentlive.tv

Photo credits:

Houses of Parliament and Garment Factory in Bangladesh by Carry Somers

Ocean by Ross Miller

In her own words Nisha is honest, hard working and devoted. Nisha is a 28 year old mother of one. She is also a sewing machine operator at the Echotex manufacturing facility in Dhaka, Bangladesh. 6 months in into her role, the biggest challenge she’s faced is picking up the necessary skills to meet the quality standards required to produce the first NINETY PERCENT collection of premium basics. Every working morning, she says goodbye to her 5 year old son and leaves her home in Shafipur, Gazipur district to catch the rikshaw to Dhaka and make your clothes.

Greatest Achievement:

Being a kind mother to my five year old son is my greatest achievement. It’s hard to find the words to express my love for my boy but I feel heaven’s peace when he runs into my arms for a hug. It makes me so proud to see my tiny boy keep himself neat and tidy and behave well around friends and neighbours.

Work highlight so far:

Completing NINETY PERCENT collection 1 is my greatest career achievement. It was a big challenge for me to make sure the finish was first class. NINETY PERCENT is exclusive product so I had to work hard to assure the quality. I learned a lot making collection 1 and I hope these skills will serve me well in future.

Best memory:

Catching fish as a child. I fished a pond near home in my native village of Bishnupur in the Gaibandha District. The best time to fish was late autumn when the water level was down and it was easier. All the boys and girls fished together then our mothers’ cooked the fresh fish for us.

Favorite place:

Cox’s Bazar – it’s the world’s largest natural sea beach. It’s an amazing feeling by the sea with the breeze and the sand. I’ve never seen any other beaches but I’m sure Cox’s Bazar is the best. Last winter the whole family went there, all the hotels and motels there are world class for all types of foreign and local tourists.

Best life advice?

My parents advised me to always be truthful. I’ve followed this advice at every stage of my life. Wherever I have been or done I have always been truthful. Actually, I think that’s my greatest achievement. It’s advice I passed on to my child – I think that’s why he is so well behaved.

The one thing you can’t live without?

My husband is my life partner – our marriage was arranged by our families. His name is Ashraful Alam and we’ve been living for 10 years. He feels my happiness and pain and tries to help me solve problems. We have a deep understanding of each other – our eyes can read each other’s hearts. My man is wonderful. He always takes care of me and shares what he thinks.

Where do you see yourself in 5 years?

In five years time I wish to be a team-leader. First of all I want to be the best most efficient employee I can – this will see me rise. My supervisor Mr. Azizul’s motivates me and boosts my self confidence. My first day in the job was a mixture of sadness, fear and happiness. I was sad because I thought I would be busy with no more free time to do what I wish. I felt fear because I didn’t know the job or the environment. I felt happy thinking about the money I would earn. Now I wake up in the early morning to complete my family tasks then say bye to my boy and leave for work. When I’m there, I complete my tasks, then return home at 5.30 pm to focus on my family again.

When are you happiest?

I become happiest outside of work when I’m with my family. We spend our time laughing, gossiping and doing lots of things. I love to play chess with my husband and cook – especially mutton curry. Before we go to sleep we always have cup of tea together at the end of the day. Making the tea for everyone is a special moment for me.

Fashion Revolution Week is here again and its mission remains unchanged: to campaign in a positive way for greater transparency in fashion supply chains. For a brand to be able (and willing) to publish details of its supply chains means that they are far more likely to be working ethically: safe, clean and fair. And knowing the true provenance of your purchases empowers you, the consumer, to make fully informed buying choices.

We’re not only willing and able to tell you about where and who our baskets come from – you can’t usually stop us shouting about the weavers and their incredible craft! We visit as many cooperatives as we can throughout the year and we’re in daily communications with most cooperative chairladies during the dry seasons when the weaving steps up a gear. It’s vitally important for us to build relationships and empathy with the people behind our baskets; to hear their stories and to see how they live. We hope that you enjoy hearing their stories, too.

Spoiled for choice as we were for whom to feature in this blog post for Fashion Revolution Week (so many interesting and inspiring people to talk about), we have decided to tell you a little more about a weaver named Ntomulan Lesania, who makes some of our Nomadic Beaded Baskets from her home in rural Ngurunit, Northern Kenya.

Back in March 2017, Camilla headed out to meet the Ngurunit Weavers Group. These weavers are semi-nomadic pastoralists (herding camels, cattle, sheep and goats) known collectively as Ariaal: they don’t belong fully to either the Samburu or the Rendille tribes – Ariaal is a mixture of the two. The Ariaal people are known for their peaceful ways and their openness to compromise, merging characteristics from both traditions – in house building, in bead making and in handicrafts – and speaking the two tribal languages interchangeably.

Ntomulan Lesania is a single mother: widowed, with six children aged between 3 and 18. She was her late husband’s second wife, and she had three children before marrying him – and then went on to have three more children with him. Here are some excerpts from Camilla’s interview with her:

The multi-coloured layers of beaded collars, headdresses and earrings worn by the Samburu women denote not only marital status but also other clues as to a woman’s rank within the tribe. Beads, buttons and sequins in different colours can signify anything from her husband’s wealth to how many sons she has birthed.

Where did you grow up and did you go to school?

I grew up in Ngurunit. I didn’t go to school. Instead, I looked after the animals in my family: goats and camels.

Do your children go to school?

Four of my six children go to school. Two boys, and two girls. The youngest two look after the family animals. I have to pay for them to attend school. Primary school is free, but secondary school is fee-paying.

Not all the children here go to school. Children who are especially good at looking after the animals will usually stay home, whilst their siblings might attend school. Sisters from the same families will sometimes be dressed differently: those who were educated will often wear more Western clothes, whilst their siblings who did not attend school wear traditional Samburu beads.

How do you make the money to pay for schooling?

I make money through basket weaving, and selling livestock, and goat and camel milk. We receive camels when we get married and we invest in livestock when we save enough money. The current drought means that livestock are dying, however. There is more drought in the area than ever before. If there are one or two failed rains, this is considered a drought, and life becomes hard for people and their businesses. Since 2006 there have been no consecutive years without drought. Recovery from a drought can take up to a year.

Life has changed considerably for Ariaal women in recent years. In this rural region of Kenya where milk is precious currency, women are now allowed to own milk-producing camels as well as milk itself. When Camilla visited in March 2017 the drought was very bad and governmental parties were slaughtering cattle to be eaten by their owners, then paying the owners for the value of that animal. This is a scheme called Food Relief, and serves the dual purposes of putting the animals to good use so that they do not starve, and feeding the people without seeing them out of pocket.

How long have you been weaving for and how did you learn?

I saw my older sister weaving, and learnt the art from her. She was only just married at that time, so still a teenager.

How does the income from the weaving help support your family?

The income from weaving helps me to buy food, pay school fees, and pay for school transport.

What makes you happy?

When my kids are around me, and we have no problems. When I am able to feed them all, and when they are happy.

What do you feel would help women to overcome the barriers they face in the working world?

More basket orders. Money helps to solve problems here. We need to earn a living.

Do you feel successful being part of a growing weaving cooperative?

Yes. We are all proud! This group is important to me: it gives me support. I am a single mother, and I get help from my friends. If I have an order to deliver, for example, my friends will help me with the children.

Ntomulan’s woven baskets – the Pambo Palm collection – were traditionally created by the Rendille people as vessels for collecting camels’ milk.

Fashion Revolution Week falls on the anniversary of the Rana Plaza factory collapse, which killed 1138 people and injured many more, on 24th April 2013. During this week, brands and producers are encouraged to respond with the hashtag #imadeyour… (insert product) and to demonstrate transparency in their supply chain.

Phann is a 40-year-old garment worker living in Phnom Penh with her husband, a security guard. Their rented room is typical for a garment worker—encased by concrete walls and covered by a tin roof with one bathroom and no kitchen. Since Microfinance Opportunities (MFO) began interviewing her in July, Phann has reported working long hours, making products for major clothing brands. She has worked 61 hours a week on average, including three weeks when she worked more than 70 hours, well above the 60-hour week maximum mandated by Cambodian law. Despite her illegal hours, she is paid 66 cents an hour according to our data, falling just short of the legal minimum wage of 67 cents per hour.

Phann, like the other 180 women participating in MFO’s Garment Worker Diaries in Cambodia, is hoping that 2017 will bring new money as the Government of Cambodia has mandated that factory owners increase the minimum wage from 67 cents to 73 cents per hour, equivalent to an increase from $140 to $153 per month [1].

Most of our diarists are positioned to receive that increase—approximately 68 percent report earning the minimum wage, if not higher. The other 32 percent of workers stand to be disappointed, according to a preliminary analysis of the data. They earn only 57 cents an hour on average, so far below the minimum wage that an almost 30 percent increase in their wages is unlikely.

Not only are they receiving less than the minimum wage, but the ways in which their earnings are calculated are often opaque, and their payment schedules are inconsistent. For instance, Mao—a 28-year-old garment worker living in Phnom Penh—received checks showing that she earned the minimum wage. During our first interview, she reported that the factory paid her $140, but she could not tell us how many hours she worked during the pay period. At that moment, we were hopeful she would be one of the garment workers who received fair wages for her work. Her next check was for $137.50, but she worked 250 hours during the pay period which equates to only 55 cents an hour. She fared better on her next paycheck, earning 68 cents an hour for 227 hours of work. However, by the time she received her fourth check, any pretense that she was receiving fair wages had disappeared. She earned $90 for 200 hours of labor, equal to 45 cents an hour.

At least Mao’s employer paid her. Chen, who works in another factory in Phnom Penh, worked 194 hours but was never paid as her employer absconded. She and her colleagues did everything possible to stop him: they attempted to block the exits to the factory to prevent his escape and sought a court order to detain him, or at least seize the assets of the factory, but those efforts proved unsuccessful. As of this writing, she has still not received any compensation for her work.

For women like Mao and Chen, and women like Phann who are paid fairly but work in excess of what is allowed by law, an increase in the minimum wage will not be enough to ensure their dignity. Brands and the Government of Cambodia must enforce the regulations that ensure fair wages and working conditions.

There has been slow progress in this regard, and a lack of transparency in the supply-chain makes evaluating the pace of progress difficult. Organizations like the Solidarity Center and Human Rights Watch are investigating working conditions to bring better transparency to the sector, but their main leverage point is to indict the reputation of the brands, a real but indirect threat to brands’ bottom lines. Consumers, with their ability to directly impact brands’ by altering their purchasing patterns, are the ultimate leverage point. For change to occur, you as consumers must demand transparency and fairness throughout the supply-chain.

To ensure dignity for these women, you must demand a fashion revolution.

[1] The legal minimum wage in Cambodia is $140 per month and is not typically reported as an hourly rate. The legal regular work week, before earning overtime, is 48 hours per week. For an average month, this equates to 67 cents per hour. The government has set the minimum wage in 2017 at $153, equal to 73 cents per hour.

The Garment Worker Diaries is a yearlong research project, led by MFO and supported by C&A Foundation, which is collecting data on the lives of garment workers in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India. Fashion Revolution will use the findings from this project to advocate for changes in consumer and corporate behavior and policy changes that improve the living and working conditions of garment workers everywhere.

Fashion design schools have an allure. Many young women in their early twenties get fashion degrees hoping to launch their own lines and drive the aesthetic of a camera-ready $3 trillion industry.

In reality, they enter a competitive market, applying for entry-level design positions in expensive cities. If accepted, they will work long days, under tight deadlines and fluorescent lights, all for salaries as low as $30,000. These graduating designers have little choice but to dive in and hope for a better future.

Interestingly enough, overseas, where roughly 97% of our clothes are made today, there are also young women in their early twenties toiling away on the assembly line. Their wages are low, working hours long, and conditions often difficult. And yet, for these young makers, factory jobs also represent hope for a better future.

Today we buy more clothes and yet somehow pay less for them. This phenomena called fast fashion, much like fast food means the industry cuts corners. What started as a way for more of us to look good on a budget has resulted in a rise in cheap, chemical filled clothes, brought to us by human hands forced to work longer hours for low wages.

But this article isn’t about shaming the fashion industry for building a broken business model. It’s about linking the amazing women on either end of the supply chain – designer and maker – to come face to face, woman to woman, to create a more human centered fashion industry.

80% of the people who are making our clothes are women, usually just 18-24 years old. Their hopes and dreams match ours: to be happy, healthy and see the world. At Remake, we pass the mic back to the women hidden at the other end of the supply chain. We have traveled to Haiti, India, Pakistan and China, to ask her to share her stories.

Our recent Remake Journey to Cambodia was in partnership with Levi Strauss Foundation and Parsons School of Fashion, home to fashion icons such as Donna Karan, Alexander Wang and Tom Ford. We took three of Parsons’ amazing graduating designers:

“As a fashion designer, we are so distant. A lot of our industry uses makers oversees and are so disconnected from them, but these are the people who are creating our work and our designs. So meeting with them and having that more manifested in our heads is a connection we need to be thinking about more.”

Meet Allie Griffin, whose great grandmother used to make our clothes right in NYC’s old garment district. Coming to a prestigious school like Parsons and recently interning at Oscar de la Renta, she feels that in one generation her family has come full circle from maker to designer.

“Fashion effects economies, politics…something you don’t normally think about. But at the end of the day there are people making our clothes, human lives depend on these jobs. That’s why fashion is important to me.”

Meet Anh Le, who designs menswear and has recently interned at American label Thom Browne. Her parents came as refugees from Vietnam, where her family worked in the garment industry. As an Asian aspiring designer, she wants to do right by creating clothes that are ethical and respect the maker.

“I’m really interested in being part of this new generation of fashion designers. We are interested in finding ethical and sustainable ways to participate in fashion. There are a lot of problems that I see, like low wages, underage workers, poor working conditions. I know a lot of my fellow students and I think it’s time to change how we make fashion.”

Meet Casey, who has designed future forward collections in collaboration with Tide and Intel. She is deeply interested in creating more sustainable patterns and textiles in union with factory systems.

Day 1: Tonlé: Zero-Waste Fashion

We visited Cambodia’s first zero-waste brand Tonlé to experience the power of fashion as a force for good. Tonlé provides at-risk women with a living wage, health care and good working hours, while also being good for our planet.

“From the moment we stepped inside the gate you could feel it, it was such a special place. There were a group of women at tables in the front yard knitting together, and they welcomed us warmly with smiles,” recounted Casey. “I spoke with Ny, a transgender male who is in charge of stock and shipping.”

“I think about how the clothes we make go all over the world. I also think that the people who buy from Tonlé really care about us, the people who make them. Most of the makers in the clothing industry come from really poor places, and they work so hard to try to achieve better lives. I want there are more brands like ours so that there are more people who have jobs as good as mine.” – Ny

Day 2: 2,000 People Making Our Jeans

We traveled down a winding bumpy and dusty road to a denim factory on the outskirts of Phnom Penh where jeans are made for every imaginable brand: from JCPenney and Kohl’s to Simply Vera by Vera Wang and J Lo.

Walking down the assembly line, you see hundreds upon hundreds of women, heads down doing fast repetitive motions, backs crunched just like ours over laptops. The sheer volume of stuff, and noise from the machines was overwhelming. All in our quest for cheap jeans.

The denim distressing unit was especially eye-opening.

“All the cuts, wear marks and washes are done by human hands, and these tasks are clearly physically demanding and even dangerous, from all the spraying of harsh chemicals. As soon as our tour ended my brain was overwhelmed with what I had just seen; how could one pair of jeans sell for $20 and have had so many hands work to produce them; the math behind where the money goes does not scream fair at all.” – Casey

That evening one of the denim makers invited us to her home for dinner in a nearby slum. We traveled in the open air truck with her, where passengers need to balance sitting on both ends to ensure the truck did not topple over. Makers in Cambodia have lost their lives in trucks just like this one, which thousands use to get to work everyday.

“I started working when I was 15. Since then I’ve worked at several different factories. My husband is sick, so my $140 a month salary support’s my whole family. I work at the factory all day and then work a second job as a tailor at night. I want my daughters to learn English and go to a school like Parsons. I’ve actually seen New York on TV and maybe someday I can come visit. I want young designers to know about my life. I have suffered but I feel stronger having met my sisters from NYC.” – Sreyneang

Sreyneang’s home was no bigger than two dining tables pulled together, the floor just dirt and the roof sheet metal. Her husband, children and neighbors all crowded in to meet us. Her home may have been small but her heart was huge. When we sat down to eat together, she kept offering us bottled water she had bought for us and took only two spoonfuls of rice. Insisting that we, her neighbors and even the stray dog and cat that stopped by had something to eat first.

“A truly inspiring, loving, and kind soul, I haven’t stopped thinking about her and I don’t think I ever will.” – Casey

Day 3: Sub-Contracted Factories, The Most Invisible People

Few things are more powerful than a room full of women who have something to say. We traveled 2 hours outside of Phnom Penh along dirt roads to a small school in the middle of rice fields, one of the few safe places makers are able to unite to talk about their rights without the police breaking up the meeting.

This gathering was hosted by Solidarity Center, to help makers fight for their rights. We learned that when big factories agree to cheap prices and tight deadlines, they often can’t meet these demands. So they ship orders off to fly by night operations–dark, dingy subcontracted factories where the conditions are the worst.

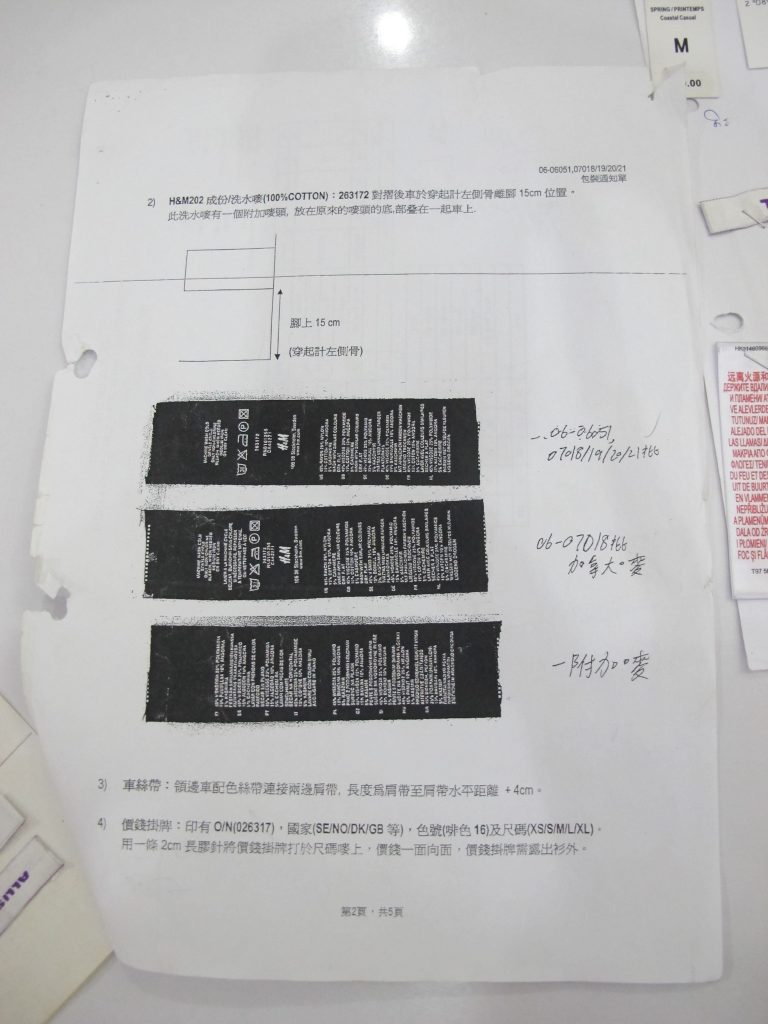

The women we met had sneaked out labels from the brands they illegally sew for including Zara, H&M and Tommy Hilfiger. It was dangerous for them to sneak these photos and labels out but they did it anyway, in the hope that we and you as readers would help them, to ask these brands pressing questions about why they worked such long hours for so little.

Some of these women made less than a $100 a month despite working all day long. Others noted that they were forced to take pregnancy tests and if it was positive, they were fired.

We learned that some factories pop-up during holiday rushes, then shut down to avoid paying the makers anything once the order is filled. Some of these women had been sleeping outside factories to get their back wages to afford food and rent. One of Solidarity Center’s incredible staff leaders Somalay, said to us,

“We will never stop. We will fight.”

She cares and risks her life, because she’s been there, she used to be a garment maker herself.

“I wanted a better life for myself and my family so I took this work at a subcontracted factory. But life has become harder. I get paid per 12 pieces, but if there’s even one single error in the batch, I don’t get paid at all. I used to make a new design every 2-3 months. Now, it’s two to three new designs per month. The designs are more complicated but we get no training. It’s harder to meet the quota. Sometimes I cry because I fear I won’t meet the quota and get paid. I hope you will help me and my colleagues by spreading our stories to the world. You being here, listening, makes me hopeful.” – Wong Char

“I definitely felt a lot of girl power throughout the day, both from our own all female crew and the makers we met. These women are not playing victims, but fighting for their rights and educating themselves on their rights. Some of the makers dressed up in professional attire, including blazers and heels and every person had a pen and paper they were furiously taking notes with. Speaking with Wong Char, I realized that the hopes she has are fundamentally no different from mine–for a fulfilling life.” – Allie

Journey #5 ended with see-you-laters, not goodbyes. Our designers and makers became friends on Facebook WhatsApp and promised as sisters to keep in touch and fight together to make fashion a force for good.

It takes 100 pairs of hands to bring each of our clothes to life. Next time you go shopping, we hope you think of Ny, Sreyneang and Wong Char and their dedication to our fashion.

We hope you join our movement and buy better from brands like Tonlé. Together we can #remakeourworld

Fashion Revolution’s theme for 2017 is Money Fashion Power which will be exploring the flows of money and structures of power across the fashion supply chain.

“There is nothing more important than performance, and fashion brands have to perform because of this greed – not a percent or two per year, but at least 10 percent quarterly, even when we’re talking about billion-dollar businesses. There is no end to the greed, so the brands are spreading themselves thin”

said trend forecaster Li Edelkoort in an interview with Deutsche Welle published this week.

Tomorrow is the fourth anniversary of the Tazreen Fashions fire in Dhaka Bangladesh. All of the garment workers were on an overtime shift to complete an urgent order when the fire alarm sounded, but managers ordered them to carry on working. As the smoke and fire spread through the building and workers eventually tried to escape, they found that iron grilles barred the windows and the collapsible gate was locked. None of the fire extinguishers appeared to have been used which suggests workers had not received fire safety training. 112 workers died and more than 200 were injured. The official who led the inquiry into the fire said

“Unpardonable negligence of the owner is responsible for the death of workers.”

After the Tazreen fire, factories were told to replace collapsible gates and lockable doors with fire-proof doors so there was always a safe exit point in the event of a fire. In the Bangladesh Accord’s initial inspection of 1600 garment factories, it was found that over 90% had lockable, collapsible gates. According to industry insiders, around 40% of all operational garment factories still have these gates, four years later.

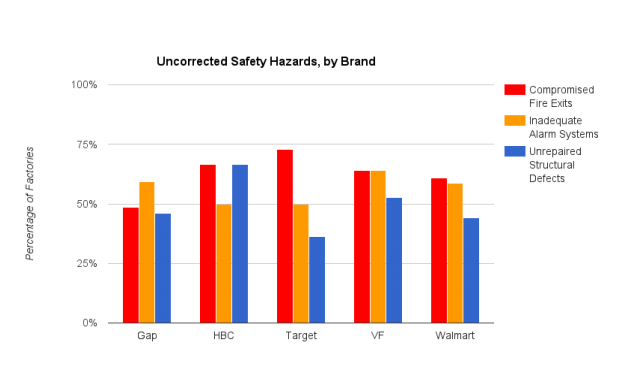

A new report published this week Dangerous Delays on Worker Safety found that of the 107 factories labelled “on track” by The Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, 99 were still falling behind in one or more safety categories. In light of Li Edelkoort’s observation that brands are spreading themselves thin, it comes as little surprise to find that brands in the Alliance, which includes brands such as Walmart, Target, Gap inc, VF Corporation (which owns Lee, Wrangler, The North Face, Vans, Timberland and others and has just published its factory lists) have yet to put in place the life-saving safety changes they pledged following the Rana Plaza disaster, which occurred five months after the Tazreen fire. 62% of factories still lack viable fire exits, 62% do not have a properly functioning fire alarm system and 47% have major, uncorrected structural problems. Deadlines for these safety measures to be implemented were supposed to be 2014/15 but have now been moved to 2018, the end of the 5 year period over which the Alliance extends.

Are brands and factory owners really so concerned with the bottom line that they cannot afford to prioritise the installation of something so basic to worker safety as a fire-proof door and the removal of locks from existing doors?

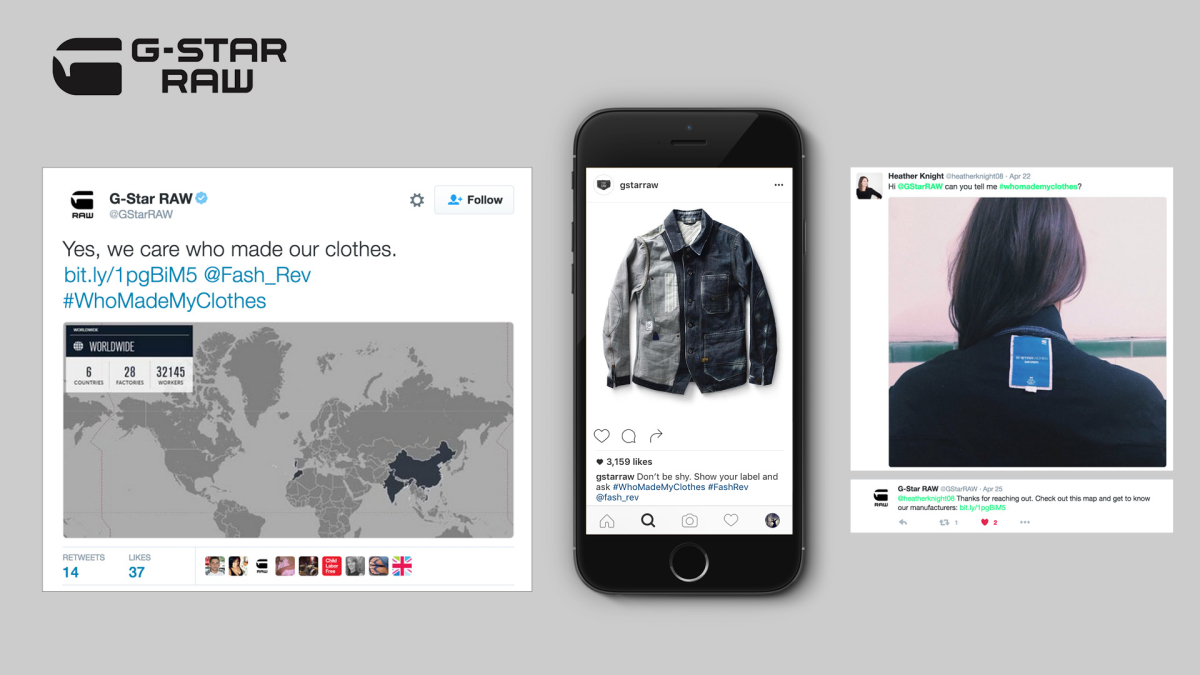

Since the Tazreen fire and Rana Plaza disaster, human rights issues are certainly more visible than ever before and there is ongoing pressure on global fashion brands to become more transparent. Companies are now being held to a higher standard and they are cognisant of this change. During Fashion Revolution Week in April, over 70,000 fashion lovers around the world asked brands #whomademyclothes on social media, with 156 million impressions of the hashtag. G Star Raw, American Apparel, Fat Face, Boden, Massimo Dutti, Zara, Jeanswest and Warehouse were among more than 1250 fashion brands and retailers that responded with photographs of their workers saying #Imadeyourclothes. Read more about our impact here.

However, the harsh reality is that basic healthy and safety measures still do not exist for millions of people who make our clothes and accessories. On 11 November 2016, 13 people died in a factory making leather jackets on the outskirts of Delhi. The front of the building had been shuttered with a metal grill which prevented the workers escaping the blaze. Deadly accidents are still commonplace in fashion supply chains and not enough has been done by brands and retailers to prevent more fashion victims; victims of neglect, oversight and the pursuit of profit.

Scott Nova, executive director of the Worker Rights Consortium says:

“What motivated Walmart and Target to do the right thing is public embarrassment. We are three and a half years on [from Rana Plaza] and they assume memories are fading.”

We have the power and, I believe a duty, to let these brands know that our memories of the Rana Plaza disaster, the Tazreen Fashions fire, and the many other tragedies which have ocurred in the name of fashion, are not fading. By asking the question #whomademyclothes we are applying pressure in the form of a perfectly reasonable question that fashion brands should be able to answer. We are asking them to publicly acknowledge the people who make our clothes; millions of people working in factories, fields, homes and other hidden places around the world. Tragedies like the Tazreen Fashions fire are preventable, but they will continue to happen until every stakeholder in the fashion supply chain is responsible and accountable for their actions and impacts.

As Li Edelkoort said, fashion brands are spreading themselves thin. As their customers, we can help make sure they start to get their priorities right and redress the imbalances of power in the fashion supply chain.

Header photo credit: A young garment worker by Claudio Montesano Casillas

La semana pasada en Copenhagen Fashion Summit, Juan Orlando Hernández, Presidente de Honduras hizo la siguiente invitación: “Si quisieran ir a Honduras a conocer por ustedes mismos, yo los recibiré personalmente en el aeropuerto”.

Ignorando las molestias en la parte posterior del auditorio que llamaron “Señor Presidente, detenga a los militares de asesinar a activistas” el Presidente de Honduras lanzó para promocionar el país como líder de exportación de prendas a Estados Unidos de América y tiene el objetivo de exportar más al mercado Europeo. La industria del vestir y textil es parte del nuevo plan Honduras 2020, un proyecto de $3.4 miles de millones, que tiene como meta hacer que Honduras sea la elección de muchas marcas para proveer de forma sustentable. “Haremos esto mediante un verdadero modelo sustentable, enfocándonos en factores clave como condiciones laborales sustentables, protección del medio ambiente, utilizando la última tecnología para reducir el consumo de los recursos, cambiando los combustibles a energías renovables” mencionó Juan Orlando Hernández, quien continuaba enfatizando el objetivo de su país por tener el 80% de sus energías de origen renovable para el 2020.

El compromiso por reducir los combustibles no renovables claramente no exenta al mismo Presidente, quien rentó un jet de lujo para ir a la conferencia de Vista Jet, entre sus clientes tienen a celebridades como Beyonce y los Beckham. La presentación del Presidente le costaría $360,000 viajando solo, de acuerdo con la información del sitio, dando esto decenas de críticas en la página de Facebook de Copenhagen Fashion Summit.

El Presidente seguía mencionando a las 1200 personas del público haciendo hincapié en cómo su país toma muy en serio el lado social de la sustentabilidad. “Gozamos de un excelente y seguro ambiente de trabajo y cuidar a nuestra gente es nuestra principal atención y responsabilidad”.

El Presidente llegó a decir que Honduras era “el segundo lugar más justo para la producción de prendas de vestir”. Después de un correo electrónico al Americas Apparel Producers’ Network, he recibido una respuesta del Director General Mike Todaro quien aclaró que el Presidente se refería al AAPN Asia/Americas Report Card. Honduras llegó al 2º lugar en el informe. Sin embargo, por lo que yo puedo ver a partir de la información en línea, sólo uno de los 8 criterios se refiere a cumplimiento social y sostenibilidad y los otros 7 incluyen elementos como el coste, la velocidad y el desarrollo de productos.

De acuerdo con War on Want, 53% de los trabajadores en maquilas o fábricas de ropa, en Honduras son mujeres jóvenes de comunidades desfavorecidas que tienen poca educación. La mayoría no son conscientes de sus derechos, la explotación es frecuente y los trabajadores están desmotivados a formar sindicatos. Solidarity Center dice que los sindicalistas son constantemente amenazados, intimidados, extorsionados e inclusive asesinados, y los criminales rara vez puestos a disposición judicial.

31 sindicalistas han sido asesinados y 200 heridos en ataques desde el 2009, de acuerdo con la federación de sindicatos AFL-CIO. De hecho en Marzo del año pasado en Departamento Americano del Empleo publicó un informe documentando abusos a los derechos de los trabajadores en Honduras. El informe detalla muchos casos donde los empleados hondureños relacionados en actos de discriminación anti-sindicalistas, imponiendo pactos anti-sindicalistas para frustrar negociaciones colectivas, así como casos donde no se pagan los salarios, exigir horas extras y numerosos abusos en cuanto a salud y seguridad laboral.

En promedio los salarios de las maquilas son equivalentes al 37% del costo de la canasta básica de Honduras. Además la diferencia entre los salarios de los trabajadores de maquilas y los de las otras industrias está en crecimiento. La competencia a la base continuará a menos que tomemos un acercamiento para tener un salario para vivir, trabajando con los gobiernos y sindicatos para ajustarlo de manera legal, imponiendo un salario mínimo en su país que asegure que los empleados puedan cubrir sus necesidades básicas.

Sin transparencia en la cadena de suministro y sin compromiso de los dueños de las marcas de moda y las fábricas de invertir en mejores condiciones laborales, los salarios y derechos de los trabajadores se mantendrán desempoderados y no podrán negociar de manera independiente sus condiciones laborales.