22-year-old Huang has been working in garment factories for about five years. Photo by Daniel Huang

I have been working in garment factories for four or five years. I am 22 years old now. When I graduated from junior high school I had nothing to do. Someone told me how good making clothes was and they introduced me to the industry. At that time I thought I was young so it would be good to learn something new. I started to make clothes then and I still do now.

I had many dreams when I was little, such as being a doctor or a policewoman or even being rich. I was so naïve then. Take the doctor dream for example. I am so scared of seeing blood. I once saw someone’s injury from a car accident. OMG, it was terrible. I couldn’t even look at the wound, let alone touch it. I even saw a dead body once. How can I be a doctor if I am so afraid of blood, injuries and death?

My plan is to work at the garment factory for a few more years but I won’t do it for the rest of my life. I will go back to my hometown to open a store in a few years. I just want to open a store, but I don’t know what kind yet.

When I graduated from junior high school, my mom asked me to keep studying but I didn’t. I was in a dilemma. My mom didn’t want me to work in the city at such a young age. She wanted me to stay in school but I was rebellious. I didn’t do well in school so I thought, “Why bother studying and spending money on my education?” I just came to the city to work so I could support myself. It was a very difficult decision for me. My mom tried to force me to study but I wouldn’t go. Honestly, I regret the decision a bit. I should have gone back to school.

For girls, it is better to learn something not so tough. I think I would learn to make patterns for clothes or something using electronic devices if I could go back to school. I want to learn something easy because I am a lazy person. I like doing finishing work for others so I don’t have to make everything from the beginning.

In terms of social life, garment factory workers like us don’t have time to take a break because we need to do overtime to keep up with production. I go out on public holidays, but there are so many people and cars during that time. I remember I went to a museum park once and I waited in line to get in from 7am to 10 am at the entrance. There were so many people there. For me, having a social life means going out shopping. Girls like shopping and buying cosmetic products. We should spoil ourselves from time to time.

For example, I once spent 2000 RMB (330 USD) to buy a set of Mary Kay products. It is a big brand that I can trust. I buy skin care products instead of make-up. It is important for me to take good care of my skin to look young and pretty because there is dirt and dust around the factory. When I first came to the city, my skin was dark but my skin is getting better with good care. I think it is better to take care of my skin as I grow older. Dirt around the factory may clog the pores in my skin and cause various skin problems. To help, I give myself facials.

Concerning other self-care, I rarely exercise. Firstly, I don’t have much time and secondly, I am too lazy. I will sleep late whenever I have a day off. I am so lazy that I miss the time to exercise. I also hate to wash my clothes because I am lazy. I think it’s best if there is a washing machine but there is no machine so I just wash the clothes myself. When I finish my shower at night, how I wish someone would wash my clothes and I could just lie in bed and play with my phone. But no one is there to help me. Even if I forget about them for half a month, I still have to wash them myself.

This interview has been edited. It was conducted on July 13, 2014 at the factory where Huang works in the industrial area of Yantian east of Shenzhen, China. You can read the original interview here

Primary Voice is a collection of primary source interviews dedicated to documenting the living stories of garment factory workers worldwide. It was created by urbanist Mikaela Kvan. To read more interviews and to get in touch visit www.primaryvoice.org

Matt is a 28-year-old garment worker in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Photo by Sok Chanrado

I’ve been working in garment factories since 2004. It’s been ten years. During those years, a lot in my life has changed. I used to live with my aunt before I started working so I would do all of the chores around her house. Now that I earn my own income I can afford to buy whatever I want and I can help my younger siblings go to school. I have two sisters and one brother. I am 28, my brother is 26, the third is 24, and the last one is 19 years old. My two younger sisters also work in garment factories but our brother goes to university.

I had a rough childhood so I want to forget about it. When I was young I sold things in the market like fish and meat. I sold anything I could. I would sell things for other people, too, in order to save for my siblings and me to go to school. We lived in Sihanoukville then and my family was poor. All of my siblings had to work to earn money for school at the age of seven or eight. In 2004, my mom passed away. That’s when I quit school.

My father was a drunk. He always caused problems – swore at us or threw things around the house or kicked us out. Because of his abuse I decided to bring my siblings to Phnom Penh to live with our aunt. After living with her for about 4 months we had to rent our own house. The financial burden was too much for her.

When I was a child I dreamt that I would finish school and get a good job that could support my family and me. When my mother died I had to quit school to work because I am the oldest sibling. I was only in fifth grade. I felt such pity for myself after quitting school. Ultimately, I had no choice. Time wouldn’t stop. I had to look forward and take care of my siblings.

I must sacrifice myself for their sake. It hasn’t been easy. At times I feel really irritated and stressed but when my siblings behave themselves, and don’t give me a hard time, I feel my capabilities are limitless. Even if we don’t have parents, we still have each other. As the eldest sibling I feel a great responsibility to be a good role model for my brother and sisters.

Financially, we can only depend on ourselves. Unlike others whose parents are still alive, we can’t survive without working. I don’t have the luxury of living that way. If it were up to me I would not work in a garment factory. I want to open a small shop where I have the potential to earn income daily. With my current job, I have to wait until the end of the month to get a paycheck from the factory. By that time, I need to pay rent and it seems I have nothing left. Unfortunately, I don’t have the ability to realize this dream for myself right now because I need to support my brother who is in university. Once he graduates I could probably quit my job at the garment factory and open my own shop. I’m optimistic about my future. When my siblings were young, I worried they wouldn’t listen to me. But it turns out my siblings are good kids. I hope the future will be easier. Since I am having a hard time for their sake now, I believe they will think about me when they have jobs.

This interview has been edited. It was conducted on August 10, 2014, outside Matt’s room in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. You can read the original interview here

Primary Voice is a collection of primary source interviews dedicated to documenting the living stories of garment factory workers worldwide. It was created by urbanist Mikaela Kvan. To read more interviews and to get in touch visit www.primaryvoice.org

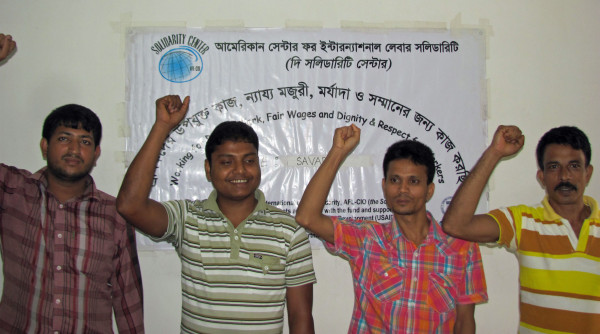

Bilkish Begum says she and other workers at a garment factory in Bangladesh could not discuss implementing fire safety measures with their employer – even after the deadly blaze at Tazreen Fashions factory killed 112 workers three years ago. Only when they formed a union, which provides workers with protection against retaliation for seeking to improve their workplace conditions, could they take steps to help ensure their safety.

“Things have improved a lot regarding fire safety once we formed union as now we have the power to raise our voice,” she says.

Bilkish, 30, now a leader of a factory union affiliated with the Sommilito Garments Sramik Federation (SGSF), is among hundreds of garment workers who have taken part in Solidarity Center fire safety trainings this year. The Solidarity Center works with garment workers, union leaders and factory management to improve fire safety conditions in Bangladesh’s ready-made garment industry through such hands-on courses as the 10-week Fire and Building Safety Resource Person Certification Training.

“I used to be afraid about fire eruption in my factory,” Bilkish says. “But after attending trainings, I feel that if we work together, we can reduce risk of fire in our factory.”

Fire remains a significant hazard in Bangladesh factories. Since the Tazreen fire, some 34 workers have died and at least 985 workers have been injured in 91 fire incidents, according to data collected by Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka, the capital. Incidents resulting in injuries include at least eight false alarms.

In January, after a short-circuit caused a generator to explode at one garment factory, Osman, president of the factory union and Popi Akter, another union leader, quickly addressed the fire and calmed panicked workers using the skills they learned through the Solidarity Center fire training. They also worked with factory management to correct other safety issues, like blocked aisles and stairwells cramped with flammable material.

Many workers who have taken part in the trainings say they are equipped to handle fire accidents.

“We are now confident after the training that we can help factory management and other workers if there is any incident of fire in our factory,” says Mosammat Doli, 35, a leader of a union affiliated with the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers’ Federation (BGIWF). “From my experience at my factory, I have seen that an effective trade union can ensure fire safety in the factory as it can raise safety concerns,” he said.

Fewer than 3 percent of the 5,000 garment factories in Bangladesh have a union. And according to the International Labor Organization, 80 percent of Bangladeshi garment factories need to address fire and electrical safety standards. Yet, despite workers’ efforts to form organizations to represent them this year, the Bangladeshi government rejected more than 50 registration applications—many for unfair or arbitrary reasons—while only 61 were successful. This is in stark contrast to only two years ago, when 135 unions applied for registration and the government rejected 25 applications, and to 2014, when 273 unions applied and 66 were rejected.

Without a union, workers often are harassed or fired when they ask their employer to fix workplace safety and health conditions.

Because his workplace has a union, which enabled Doli to participate in fire safety training, he—like Osman and Popi Aktee—already has potentially saved lives. Together with other union leaders, he helped evacuate workers and extinguish a fire in their garment factory.

Shahabuddin, 25, an executive member of his factory union, which is affiliated with SGSF, is among Bangladesh garment workers who see firsthand how unions help ensure safe and healthy working conditions. He says his workplace had no fire safety equipment—until workers formed a union and collectively raised the issue of job safety.

“Now management conducts fire evacuation drills almost regularly. We did not imagine it just a few years back. As we formed union, many things started changing,” he says.

Mushfique Wadud is Solidarity Center communications officer in Bangladesh.

The three-year anniversary of the November 24, 2012, fire that killed 112 Bangladesh garment workers at the Tazreen Fashions Ltd., factory offers a time to reflect on garment workers’ ongoing struggle for workplaces where they will not be killed or injured and for jobs that will support their families.

The Tazreen fire was preventable, as was the collapse of the multistory Rana Plaza factory five months later in which more than 1,130 garments workers died and thousands more were severely injured.

Workers at Tazreen and Rana Plaza did not have a union or other organization to represent them and help them fight for a safe workplace. Without a union, garment workers say they are harassed and even fired when they raise safety issues with their employer. They are not trained in basic fire safety measures and often their factories, like Tazreen, have locked emergency doors and stairwells packed with flammable material.

Despite the many obstacles to forming organizations and achieving a voice at work, garment workers are at the forefront of pushing for change at their factories. With our strong and long-term grassroots connections in Bangladesh, the Solidarity Center allies with garment workers to provide ongoing training for factory-level union leaders on topics such as gender equality, workers’ legal rights and fire safety.

This photo essay gives voice to the sorrow, but also the hope, of the 4 million workers who toil in Bangladesh garment factories.

1. Bangladesh’s 4 million garment workers, mostly women, toil in 5,000 factories across the country, making the $25 billion garment industry the world’s second largest, after China. Yet many risk their lives to make a living. In the three years since the fatal Tazreen Fashions Ltd. factory fire, some 31 workers have died and at least 935 people have been injured in garment factory fire incidents in Bangladesh. Credit: Law at the Margins

2. Some 112 garment workers were killed in a blaze that swept through the Tazreen factory on November 24, 2012. Hundreds more were injured and like Tahera (above), will never be able to work again. Survivors say they endure daily physical and emotional pain, and often cannot support their families because they cannot work and have received little or no compensation. Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

3. Tens of thousands of Bangladesh garment workers held rallies on May Day this year to highlight the need for the freedom to form worker organizations to ensure safe and healthy workplaces. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

4. With few jobs available that pay a living wage, more than 600,000 Bangladeshi workers migrate each year. Yet, “after two years, after three years, they are not getting their salary,” says Sumaiya Islam, director of the Bangladesh Migrant Women’s Organization (BOMSA). “After spending $1,000 (to labor recruiters), they are not getting paid.” Credit: Shahjadi Zaman

5. Migrants from Bangladesh also risk their lives when going overseas for jobs. In June, Bangladesh families rallied to demand the government punish traffickers after many Bangladesh workers were among migrants stranded on abandoned boats by unscrupulous labor traffickers. “I did not get anything to eat for 22 days and just survived by eating tree leaves,” Abdur said, describing his journey to Malaysia. Credit: Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

6. On April 24, 2013, the multistory Rana Plaza factory collapsed, a preventable tragedy that killed more than 1,100 garment workers and injured thousands more. On the two year anniversary in April, family members and friends gathered at the site of the building to commemorate their loss. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

7. Thousands of garment workers, like Mosammat Mukti Khatun (above, looking at the Rana Plaza rubble) who survived the Rana Plaza disaster, remain too injured or ill to work and support their families. Survivors and the families of those who lost loved ones in the collapse say they are struggling to make ends meet, unable to pay rent, send their children to school or provide for other basic needs. Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

8. Days before tens of thousands of Bangladesh garment workers rallied on the two-year anniversary of the Rana Plaza collapse, the ITUC released a report that found “a severe climate of anti-union violence and impunity prevails in Bangladesh’s garment industry. The violence is frequently directed by factory management. The government of Bangladesh has made no serious effort to bring anyone involved to account for these crimes.” Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

9. The Solidarity Center launched the Bangladesh Worker Rights Defense Fund in April 2014, following an increase in violence and harassment against workers who were seeking to form unions to protect their health and rights on the job. Donations of more than $15,500 helped to provide costly medical treatment for organizers beaten or attacked while speaking to workers about their rights, and temporary food and shelter for workers fired for trying to improve their workplace. Credit: Solidarity Center/Shawna Bader-Blau

10. Despite employer and government resistance to workers’ efforts to form organizations to improve job safety, in the Dhaka export processing zone alone, 40 of the 103 factories include workers’ welfare associations, which are similar to unions. Credit: Solidarity Center/Mushfique Wadud

11. Women garment workers primarily fuel Bangladesh’s $25 billion a year garment industry, yet women are “still viewed as basically cheap labor,” says Lily Gomes, Solidarity Center senior program officer for Bangladesh. “There is a strong need for functioning factory-level unions led by women,” says Gomes, who is leading efforts to help empower women workers to take on leadership roles at factories and in unions throughout Bangladesh. Credit: Solidarity Center/Kate Conradt

12. With strong and long-term grassroots connections in Bangladesh, the Solidarity Center provides ongoing training for garment worker union leaders on topics such as gender equality, workers’ legal rights and job safety. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

13. Garment worker union leaders sharpen their skills through regular Solidarity Center workshops, such as this one on financial management. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

14. Hundreds of garment worker union leaders have participated in this year in the Solidarity Center’s 10-week fire safety certification course. “People who worked at Tazreen and Rana Plaza had no training and had no union,” says Saiful, who took part in a recent fire training. “This training is about making sure those things never happen again.” Credit: Solidarity Center/Rakibul Hasan

Sunday is the only day off for garment workers in Myanmar. Almost ninety per cent of garment workers in Myanmar are women. Sunday Café takes place every Sunday at Thone Pan Hla in Hlaing Thar Yar distric in Yangon. Thone Pan Hla is the first association for women garment workers in Myanmar, established in 2014 by Business Kind Myanmar.

Hlaing Thar Yar distric is the area where most of garment factories are.

Thone Pan Hla offers an opportunity for women garment workers to meet, share their experiences, get vocational training and participate in workshops. It is also a place where garment workers can relax, laugh and enjoy their free time. They can have access to magazines, books and different services, like kitchen and laundry, that otherwise wouldn’t be able to reach due to their low salaries. Swiss House is Thone Pan Hla headquarter and hosts also a hostel. Often garment workers come to work in Yangon from different areas all over the country and finding accommodation is not taken for granted.

The name Thone Pan Hla came from the name of a traditional Myanmar flower that unfortunately now is becoming rarer and rarer. It is a flower that changes colour three times a day. The name has been chosen to recall the three faces the working women have to wear: one intimate-private, one at work and one for her family.

I got the chance to participate two times at Sundays Café this summer during my internship at Business Kind Myanmar. In order to celebrate the Myanmar national holiday 19th July, Thone Pan Hla members prepared a fashion show with dresses designed by themselves and a theatrical performance narrating the story of women that have come from the countryside, arrive in Yangon in order to find a job. She finds a job in a garment factory where she is not well treated, but while discouraged she is going back to her family, she met an other woman that helps her…

The pictures were taken during the show, the preparation and the celebrations.

To learn more about Thone Pan Hla follow them on Facebook

To learn more about Business Kind Myanma

Pictures by Chiara Tommencioni Pisapia

I am sure that you have a closet overflowing with clothing. Chances are you might even have items that still have the swing tickets attached. Have you ever looked at the care label to see where your clothing was manufactured? Fast fashion isn’t going anywhere anytime soon. In fact fast fashion was created for this simple reason: to get us buying more and more and without much thought into where these garments are made.

I am hoping that by the time you finish reading this piece, something would have shifted. For one you will take a look at the care labels of your clothing and find out who is responsible for it and that you will hopefully reevaluate your shopping habits. Fast fashion companies cut corners, they use cheaper fabrics and cheap labor. It is simply exploitation. There is the argument that fast fashion creates jobs but when people are exploited it simply isn’t right.

Cape Town was aflutter recently when H&M (Hennes & Mauritz) opened its first store in South Africa. More stores are planned including Johannesburg’s Sandton City as well as others in Southern, East and West Africa.

It is always great to have brands open stores in our country, least of all when you know that jobs will be created. It is reported that about 600 jobs were created leading up to the opening of the V&A Waterfront and Sandton City stores. Staffers, around 60, were sent to Sweden for training. H&M plans to have as many as 1 500 people employed within the next 12 months.

The buzz continues but there is one fundamental problem with brands like these and it seems very few people know what really happens behind closed doors. In this case, behind the doors of the factories that produce these garments. This lack of knowledge was evident from the social media images from fashion bloggers to local personalities applauding H&M on their opening.

It was not long ago, in fact only two years prior, in April 2013 when the deadliest industrial disaster in the history of clothing manufacturing took place. The collapse of the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh, claiming the lives of 1 138 of its workers.

Two years after this tragedy, H&M is still behind on correcting the fire and safety hazards in its factories in Bangladesh according to the joint report released by the International Labor Rights Forum, Clean Clothes Campaign, Maquila Solidarity Network, and Workers Rights Consortium. These fire and safety hazards are the working conditions their workers are forced to work under making sure that fast fashion reaches our stores timeously. Repairs, which include installation of fireproof doors and the removal of locking or sliding doors from fire exits are some of the issues that have not been addressed.

These are repairs that affect the staff working in these factories. If not dealt with, it could have disastrous outcomes, like that of April 2013. It appears that more attention is placed on pushing out the orders as opposed to the people who make these garments. Will these factories get away with these hazardous conditions if they were in developed countries? No! Cheap labor is simply that; cheap. Bangladeshi workers who sew for H&M toil in extremely dangerous conditions. So can you really say that their fashion is cheap? Cheap in price definitely but costly on the scale of human lives. Par Darj, the country manager for H&M South Africa described H&M’s merchandise as “democratic fashion” high quality, easy and affordable for people who ordinarily might not be able to buy fashion. How democratic is this model if H&M chose to open their first store at the V&A Waterfront? The only people who benefit from the fast fashion system are the executives who are some of the richest people in the world.

The H&M store in Cape Town is 4700 square meters and is said to be one of their biggest stores in the world. Rumor has it that there might be a section carrying local designers in the near future. Could this be why they are exploring the feasibility of opening a local manufacturing facility? Par Darj said H&M already has a production factory in Ethiopia, opened in 2014. “We will see what is possible in South Africa”. One would hope that the working conditions in this factory are safer than the one in Bangladesh or the potential of a factory opening in South Africa will not cost anyone their life.

Are South African malls in the future only going to comprise of top international brands? The likes of Burberry, Forever 21, Top Shop, Zara etc. It could be, unless you reevaluate your shopping habits.

The True Cost film will make you rethink your fast fashion addiction. I can’t help but think of the interview with Shima Akter, a 23-year-old Bangladeshi garment worker who was beaten by her factory supervisors for organizing and leading a workers’ union in the hopes to get better working conditions ‘I don’t want anyone wearing anything which is produced by our blood.’

I encourage you to watch The True Cost to understand just where your clothing comes from and the price others are paying for it.

Who Makes Our Clothing? | Livia Firth | The True Cost