Fashion Revolution Week is here again and its mission remains unchanged: to campaign in a positive way for greater transparency in fashion supply chains. For a brand to be able (and willing) to publish details of its supply chains means that they are far more likely to be working ethically: safe, clean and fair. And knowing the true provenance of your purchases empowers you, the consumer, to make fully informed buying choices.

We’re not only willing and able to tell you about where and who our baskets come from – you can’t usually stop us shouting about the weavers and their incredible craft! We visit as many cooperatives as we can throughout the year and we’re in daily communications with most cooperative chairladies during the dry seasons when the weaving steps up a gear. It’s vitally important for us to build relationships and empathy with the people behind our baskets; to hear their stories and to see how they live. We hope that you enjoy hearing their stories, too.

Spoiled for choice as we were for whom to feature in this blog post for Fashion Revolution Week (so many interesting and inspiring people to talk about), we have decided to tell you a little more about a weaver named Ntomulan Lesania, who makes some of our Nomadic Beaded Baskets from her home in rural Ngurunit, Northern Kenya.

Back in March 2017, Camilla headed out to meet the Ngurunit Weavers Group. These weavers are semi-nomadic pastoralists (herding camels, cattle, sheep and goats) known collectively as Ariaal: they don’t belong fully to either the Samburu or the Rendille tribes – Ariaal is a mixture of the two. The Ariaal people are known for their peaceful ways and their openness to compromise, merging characteristics from both traditions – in house building, in bead making and in handicrafts – and speaking the two tribal languages interchangeably.

Ntomulan Lesania is a single mother: widowed, with six children aged between 3 and 18. She was her late husband’s second wife, and she had three children before marrying him – and then went on to have three more children with him. Here are some excerpts from Camilla’s interview with her:

The multi-coloured layers of beaded collars, headdresses and earrings worn by the Samburu women denote not only marital status but also other clues as to a woman’s rank within the tribe. Beads, buttons and sequins in different colours can signify anything from her husband’s wealth to how many sons she has birthed.

Where did you grow up and did you go to school?

I grew up in Ngurunit. I didn’t go to school. Instead, I looked after the animals in my family: goats and camels.

Do your children go to school?

Four of my six children go to school. Two boys, and two girls. The youngest two look after the family animals. I have to pay for them to attend school. Primary school is free, but secondary school is fee-paying.

Not all the children here go to school. Children who are especially good at looking after the animals will usually stay home, whilst their siblings might attend school. Sisters from the same families will sometimes be dressed differently: those who were educated will often wear more Western clothes, whilst their siblings who did not attend school wear traditional Samburu beads.

How do you make the money to pay for schooling?

I make money through basket weaving, and selling livestock, and goat and camel milk. We receive camels when we get married and we invest in livestock when we save enough money. The current drought means that livestock are dying, however. There is more drought in the area than ever before. If there are one or two failed rains, this is considered a drought, and life becomes hard for people and their businesses. Since 2006 there have been no consecutive years without drought. Recovery from a drought can take up to a year.

Life has changed considerably for Ariaal women in recent years. In this rural region of Kenya where milk is precious currency, women are now allowed to own milk-producing camels as well as milk itself. When Camilla visited in March 2017 the drought was very bad and governmental parties were slaughtering cattle to be eaten by their owners, then paying the owners for the value of that animal. This is a scheme called Food Relief, and serves the dual purposes of putting the animals to good use so that they do not starve, and feeding the people without seeing them out of pocket.

How long have you been weaving for and how did you learn?

I saw my older sister weaving, and learnt the art from her. She was only just married at that time, so still a teenager.

How does the income from the weaving help support your family?

The income from weaving helps me to buy food, pay school fees, and pay for school transport.

What makes you happy?

When my kids are around me, and we have no problems. When I am able to feed them all, and when they are happy.

What do you feel would help women to overcome the barriers they face in the working world?

More basket orders. Money helps to solve problems here. We need to earn a living.

Do you feel successful being part of a growing weaving cooperative?

Yes. We are all proud! This group is important to me: it gives me support. I am a single mother, and I get help from my friends. If I have an order to deliver, for example, my friends will help me with the children.

Ntomulan’s woven baskets – the Pambo Palm collection – were traditionally created by the Rendille people as vessels for collecting camels’ milk.

Fashion Revolution Week falls on the anniversary of the Rana Plaza factory collapse, which killed 1138 people and injured many more, on 24th April 2013. During this week, brands and producers are encouraged to respond with the hashtag #imadeyour… (insert product) and to demonstrate transparency in their supply chain.

From the very beginning, our artisans have always been our partners in positive change and empowerment! The journey of R2R, after all, really started with them. It was through their amazing talent of weaving and this artistry’s capacity to transform lives for the better that R2R became what it is today.

We’re pretty sure you’ve met some of our artisans in our Weaving with the Weavers events or even in our stores –– yes, some of our store ambassadors are artisans, too! But we have a wonderful (but very elusive!) group of artisans we’d love to introduce to you. You don’t get to see them often because these are our workshop artisans! They’re the ones running our humble workshop, assembling your bags to perfection before they land in our stores.

In honor of Fashion Revolution Week, we’re going to take you through our workshop and introduce to you the faces behind our production process!

1. NHING ESTABILLO, WORKSHOP SUPERVISOR

Ate Nhing started as an urban artisan from our Payatas community back in 2008 and since 2012, she’s been in charge of our workshop’s overall production, monitoring targets and making sure her team of amazing artisans create high quality bags and home items for you, our dearest advocates.

Update: Ate Nhing is now our Sales Ambassador! You can meet her in our Trinoma or UP Town Center stores!

2. BERNABE “BING” LOR, TEAM LEADER OF CUTTING

Kuya Bing, as we call him, is the lead of our workshop’s cutting team. Cutting is the very first step in our workshop’s production process! He and his team lays out the foundation of the bags by cutting and preparing the raw materials needed to make R2R bags. Once they’re done, the materials then get passed onto the other steps of our production process!

3. RUFINO “JUN” GAYANILO, JR., TEAM LEADER OF ASSEMBLY

Kuya Jun leads our workshop assembly. Once all the raw materials –– from the handwoven fabric to the bags’ hardware –– have been prepared, he and his team take all these different parts and put them together to build the R2R bags that you own and use today.

4. JIMBO ZIPAGAN, TEAM LEADER OF SEWING

Kuya Jimbo is our workshop’s sewing team leader! He’s in charge of the major and minor sewing of all our bags and home items. Even with that big of a responsibility, he’s one of the people in the workshop who’s always wearing such a huge and happy smile! It’s SUPER contagious, we swear!

5. FLORENCIA “FENCIA” FONTE, TEAM LEADER OF QUALITY CHECKING

Ate Fencia leads the workshop’s quality checking team or QC, as we call it! They’re the ones making sure that each and every bag is up to par with our standards of excellence. We don’t just QC the pieces after it’s done; we also check per stage so we see if each part of the bags were prepared properly, from the handwoven fabric to the cut leather. It’s a very important step of our production process because we always want to deliver high quality pieces to you, our advocates.

In R2R, we believe that fashion can be made in a safe, clean, and beautiful way and where creativity, quality, environment, and people are valued equally. That’s why we think it’s super important to ask the questions: #whomademyclothes, #whomademybags? Join the Fashion Revolution!

Header photo: Carry Somers, co-founder of Fashion Revolution, visits the Rags2Riches workshop in October 2016.

80% of our fashion is made by women (mostly 18-24 years old) but we only hear about these millennial makers when they’re associated with a tragedy like Rana Plaza in Bangladesh in 2013 or the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York in 1913. Their stories are eclipsed by heartbreaking headlines that hound the fashion industry.

But there is another part of this story. It’s a story of hope. Remake has traveled to factories and dormitories throughout the world in search of the women who never make the headlines. Kashmiri who opens the yarn to make it into fabric. Maud and Rubina who stitch our blouses and jeans together. Anju who pulls out loose threads and inspects everything to ensure perfection. Each has a story and a hope for a very different future.

Meet the women behind fashion’s supply chain — we followed them from Haiti to Pakistan to China — and asked each of them to share a message to you, the end shopper. These are their stories:

Kashimiri, Yarn opener, Panipat, India

I am 25 years old and already have 4 children. I sit crouched on the floor all day, opening spindles of yarn which go on to become fabric. Panipat has a lot of needs. Open sewers, flies and trash everywhere. Only recently my children starting going to school. I now hope that they will have a better future. Go on to be somebody. I hope you can see their faces in the threads of your fabric.”

Rubina, Hoodie Sewer, Karachi, Pakistan

I am 22 years old and wanted to be a doctor. Then my father got sick, so here I am, many years later, still at a factory stitching college sweatpants and hoodies that go to America. I don’t want you to feel sorry for me. I used to be shy and scared in the factory environment. But after all the injustices I’ve seen happen here, I’ve become a labor organizer. I go to management to demand that we are not harassed, paid on time, given proper food to eat. You would not believe the things I have seen. Stitching all day long my mind wanders and I think about you often. You having fun, wearing these hoodie on campus. I wonder if you think about me ever? The woman who made that for you. I am taking English classes at night. So that one day I can at least get an office job.

Maud, Jeans Sewer, Ouanaminthe, Haiti

The factory across from the Massacre river is like paradise, with its lush green trees and paved roads. I’ve been sitting down sewing your jeans here for five years. Recently my back and neck has been hurting a lot more. But without this job, I have no way to support myself or my six siblings. After a long day, I walked across the river into my community which is pitch dark at night. There is no electricity or running water, just human need everywhere. I want to save enough to go back to university and study computer science. I want you to think about your sister Maud in Haiti, when you put on your jeans. On dark sad nights I play on Facebook with my phone and dream of the day I can be just like you.

Zheng Ming Hui, Quality Assurance, Guangzhou, China

At 19 I left my village to experience the excitement of city life. Here I am three years later, still at the same factory. I work 12 hours a day, looking at beautiful, bright patterns to make sure that there are no defects. My mother wishes I would call her more. But mostly I miss my grandmother. I only get to see my family once a year for Chinese New Year and mom makes the biggest feast. My entire life is the factory. I live in the dorms with three roommates, work all day only stopping to eat at the cafeteria. On my one day off, I am too tired to do much so I play with my phone. At night I dream of bungee jumping. I want to find someone to fall in love with and travel the world for work, taking pictures and telling stories. But for now, I am here, making sure your clothes look nice. I picture you and I am sure you look BEAUTIFUL!

Anju, Fabric Inspection, Delhi, India

I once dreamed of a life that was very different. Where I could finish my education and become a teacher. Everything changed when I was 15 and married to a man with few means. For the last 10 years, I’ve been working in a factory instead. I am proud to be an equal bread winning partner with my husband and to know that my hard work allows my children to go to school. I stand on my feet all day, pulling loose threads out of finished blouses and tops. Making sure they are perfect for you. I want you to know that I recently took a health education course on making nutritious meals with little money. I now teach what I’ve learned at my children’s school on my day off. I guess my dream of becoming a teacher has come true after all.

A 100 pair of human hands touch our clothes before they get to us. Each one of these mothers, sisters, wives and daughters are fierce and hard-working. Dreaming like us to be healthy, happy and financially secure.

Share these stories on Twitter and Facebook with your favorite brands and say: I want to know the invisible people #whomademyclothes.

Together we can #remakeourworld

What kind of a boyfriend (or life) do you have?

Thankfully, as the case against cheap clothing is reaching maturity, more and more consumers are becoming aware of fast fashion’s negative impact on people and planet. Documentaries such as the True Cost and high profile campaigns (and campaigners) are rapidly changing public perceptions and we are now more informed than ever.

Cheap clothing costs.

It costs environmentally and socially. It is as inefficient as it is polluting. It is rooted in the exploitation of both human and natural resources and as consumer awareness grows we begin to see an increased sense of outrage when we spot blatant cases driving this cheapness even further.

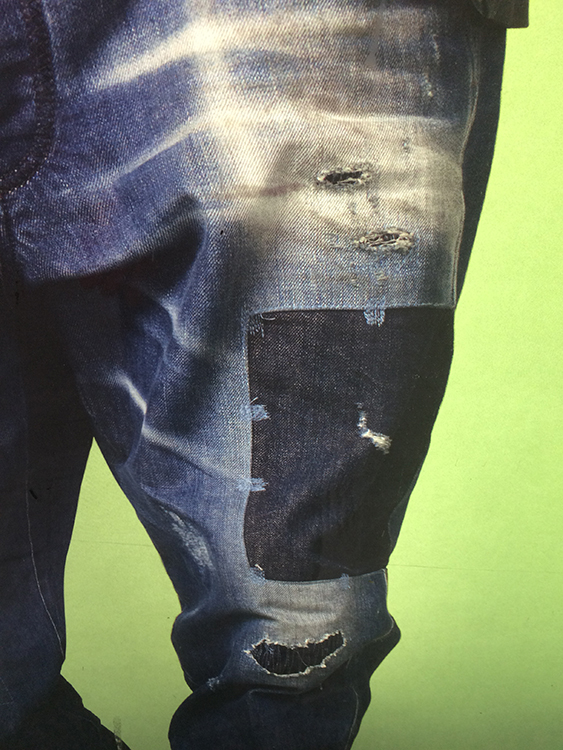

Right now it’s the lidl boyfriend jeans, at £7.99. The denim range starts at £5.99. One pair of jeans: £5.99.

Ridiculous may not be a strong enough word to describe the phenomenon, but it nevertheless is worthy of all our ridicule because for this ridiculous looking pair of jeans, like millions of other pairs of cheap jeans, the point is not just how much we are prepared to compromise in order to own them, such as the self respect of the people who made them (cheap jeans = cheap labour) and the environmental footprint they come laden with, but how stupid we are prepared to look like when we wear them.

Poorly made, poorly designed fast fashion pieces, produced in their millions, lack all individualism. In the case of denim, this lack of individualism speaks volumes.

Jeans, we live in them; they have become so ubiquitous we could call them humanity’s uniform.

They have crossed all cultural barriers and have represented our social and political attitudes, from utilitarian workwear in the early 1900s, to a symbol of the hippy peaceful protests in the 1960s, to punk. Everyone wears jeans: millionaires, refugees, celebrities and school kids.

A canvas that is the fabric of so many stories.

When I was growing up, it was Levi’s 501s or die. Nick Kamen stripped to wash them in a launderette, ripped jeans wearers were banned from Harrods and one would spend hours in a cold bath to mould them to fit perfectly. If you were an artist they would be splattered in paint, if you were a gardener they would gather earth in their turn-ups. They were never ironed, seldom washed. Quite a few people learned how to sew in the early 80s in a desperate move away from the 70s bell bottoms, to take them in at the seam and make them skinny.

We have no time for that anymore: now we want our jeans lived in even if we are not. Even if we are so boring and we do nothing at all all day but stare at our screens, our jeans have to say ‘ripped’ and ‘worn’ and ‘used’…like…what a life!

So, what kind of a ’life’ is your customer’s supposed ‘boyfriend’ having then, Lidl?

If we analyse the jeans anatomically, we can deduct that he wears his denim unbuttoned and slightly pulled down most of the times (see wrinkles at the top) and that he spends an inordinate amount of time with his trousers down, rubbing his thighs with something rough.

At one point he was mauled by a dog who bit his right leg, or perhaps he stumbled upon some sharp object (no blood of course) and either he is good at sewing, or his mum is, because he bothered to patch the rip up.

And, every single woman who buys the Lidl boyfriend jeans will have the same pattern of usage on her trousers as everyone else: the same rip (patched), the same wear (unnatural), the same wrinkles (trousers down = downright perv if you ask me).

In fact, if you take Lidl’s jeans and other pre-distressed denim from our generation, put them in a box and leave them, say, 1000 years, any future anthropologist looking at them would conclude that humans around 2016 were doing all sorts of really weird stuff, according to how they ‘wore out’ their jeans: hours rubbing bums on rough surfaces, crawling constantly, wearing trousers down instead of up, accidentally misusing acid, having violent tussles with wild animals on a regular basis à la Revenant, and most possibly suffered regular episodes of scabies in particular on shins and thighs.

Distressed denim is the symbol of fast fashion; its most perfect visualisation.

It shows how unintelligent it is, how undesigned it is. It shows how, for the sake of looking exactly like everybody else and owning cheap stuff, we are compromising on who we are as individuals and compromising on the wellbeing of our planet and the people who make our clothes.

It takes 1.800 gallons of water just to grow the cotton and produce a pair of jeans (without considering how many times they will be washed in their lifetime) and most distressing techniques have a radically negative effect not just on the fabric but on the environment and garment workers as well. Sandblasting, a technique which was widely used to achieve the worn look for well over 20 years, was eventually banned internationally as a result of its direct link with silicosis, a deadly respiratory disease.

There is no joy in owning these jeans.

They are a monument to all that has gone wrong with this industry. A monument to speed and impatience, the physical manifestation of a senseless race to the bottom with its dramatic social and environmental consequences.

Fashion Revolution encourages the alternative use of jeans, such as Mud’s leasing scheme and Nudie’s in-store repair services. We salute the companies innovating in this field: brands such as Monkee, Hiut, G-Star Raw and a handful of others who are breaking with this horrendous modern tradition by using organic and recycled materials and designing denim as what it is: a durable, versatile fabric that has had the power to capture our imagination like no other.

Let’s celebrate this miracle material as a success story, the fabric of our society, the one cloth that has had the power to become a form of political expression, and not turn it into the symbol of how we got things so spectacularly wrong.

Shubhangi Singh Rathore works as a Production Merchandiser at Sadhna Handicrafts in Udaipur, India.

As a Production Merchandiser at Sadhna, I follow up with suppliers and coordinate the organisation’s internal production related work. I love my work. I studied my masters in Fashion Management and took this particular work as a profession. I am now implementing and executing the theory and knowledge that I have gained from studying.

Before working at Sadhna, I was working in Delhi as a Buyer in the ladies ethnic department with Texas Pacific Group (TPG) Wholesale Pvt. ltd-Vishal Mega Mart. They’re the biggest private equity firm, owning Visual Mega Mart, one of the biggest retail chains in India. It’s huge. That was my first job.

When I was a child, I thought I would become a naval officer! I used to watch a television program that used to play on Doordarshan and the name was Abhiman, which was based on the navy. My career aspirations changed every now and then, but that was the very first initial idea in my mind.

Soon after my graduation I got more inclined towards brands. This is because my friends were very brand savvy. Until the time of graduation, I was not a very brand savvy person. After meeting my friends who were quirky, I started hearing words like Zara, H&M and Abercrombie and Fitch. It sounded to me like there was a big brand garment industry out there.

My mum always used to compliment my eye. She would say I have a great taste in colour combinations and styling. Even if not always in regards to my own styling! So I thought fashion industry was a good choice for me to pursue a career with.

When I started my career in fashion I worked as a Buyer, now I am on the flip side, I am a vendor. When I was a buyer I was dealing with the vendors and regularly facing some challenges, such as with vendor management, timely deliveries and sales at better mark ups. On the other side, I know what the challenges are. Now with the blend of both jobs, I am able to bridge that gap. It’s not ethnic, western, whole, woven or knits, it’s about the knowledge that you acquire and gain and using this to get better designs. I will stay in production and upgrade my skills.

I decided to come back to my home town as it had been quite a long time away with my studies, internships, working and everything. I found some work in my own home town within the fashion industry. I was so lucky to get associated with Sadhna.

Five years down the line I see myself as a Category Head. This could be either with Sadhna, if it grows and thinks of having Category Heads in the future, or maybe with another brand.

As a Buyer, I have been to places where there are women operators and male operators. In other factories and setups I have been to people are more confined. They enter work and go. At Sadhna it’s more of a family. I feel whatever thoughts you have in mind when walking into the factory you can share it easily with another person. Here through chatting people can shed off their office and home load and when they exit, they take happy memories. I always notice that with the tone when the pitch is high everything is normal. Sometimes I witness quarrels, but it’s when people speak in whispers, “I think something fishy is going on!” When the buyers visit they hear shrieks and are like “my god, what is all the noise?” and I say “chill, we are laughy, chatty and noisy like a family!” Still, people work very hard. Sadhna keeps the balance between the corporate and social sector. We completely do not want to operate a corporate factory with no emotions. In terms of output and systems we are trained and documents are recorded. All the teams have documents, instead of documentation being in a person’s mind. We give more and more training on this. Even the work that I do, the coordination and follow ups, I always tell people this file contains these items, if I am not here you know how to document it.”

My previous boss, Mr Bharat Bhatia, was my role model. He had 16 years’ experience with knits and was a person who used to see a garment from the distance and be able to tell the price of the garment. In Sadhna, I admire Swati for her overall production handling expertise and Manjula for skills in handwork. Every now and then I make somebody new my role model. In the movies, I like Ahmed Kahn. I really like Sushmita Sen who was an ex Miss Universe. She is beautiful and independent and she is a single mother, very known. She is doing very big things for society but not that many people know about it.

There are so many challenges for working women in India today. Firstly, the society is the biggest challenge, then the family is the second one and the inner consciousness, which has been made stubborn, is the third one.

In Indian culture everything is a blend with the society. Society pesters every now and comes up with thoughts and with facts, which pressurizes a woman to change her decisions. I will give you an example, suppose if girl is aged 22 or 23 and further wants to work, the society will keep pestering the parents saying “this is her marriageable age, you should marry her off, why aren’t you marrying her?” or they will say “that girl got married, this girl got married, why isn’t your daughter married?” The society is always pressurizing parents and then families are pressurizing girls and women.

Inner conscience is meant in the sense that some girls know what they really want to do. But they then limit themselves and they create boundaries, therefore they never do what they really want to. If women really want to travel they should! But women won’t do it because the inner consciousness keeps telling them “you are an Indian girl, you don’t have to travel, you just have to be at home and if you want to travel it should be just 20kms to-and-fro, not more than that”. Women who do travel on their own in India are great. But generally, they are at home but travelling to fetch the wood to cook at night, they get water from the pumps, which is actually more travelling than men. But not enough in the outside world and women really want to travel more.

Personally, I would love to travel more, I have been doing it quietly, and especially when I was away from home I would travel to find out more about different cultures, meet people, learn songs in local languages and take lots of pictures! Now I am home, again you see it’s the inner consciousness that tells me: “how do I tell my parents I want to go out? I have to come up with reasons that I have planned a party or I have planned a vacation”. When I was living outside of my hometown in hostel, I didn’t need to explain. When you are at home, you are in front of the eyes of your parents and they keep a note of everything.

The main challenges for women in India are to work as per their choice, to marry as per their choice, to decide whether to stay in a family or to stay all by themselves, and studies, choosing disciplines as per their choice. There are more women studying now in India but difficulties still remain.

For International Women’s Day, Sadhna is planning an event on 8th March. We will play some games, to make the women feel special. Before I started working with Sadhna, I was not familiar with the views of “for the women, of the women, by the women,” I’d heard them in a democratic sense. We need to expand these prepositions with women. I want everyone to feel proud to be a woman that would be my message for International Women’s Day.

Just before the onset of New York Fashion Week, Burberry announced a radical shift in how their collections will be shown and sold: no longer following the usual fashion schedule of two menswear and two womenswear seasonal shows, but instead amalgamating them into two gargantuan annual shows and, crucially, making the collections available to buy immediately, eliminating the concept of ‘previewing’ to buyers before the clothes are made available to the customer.

Within a few days, Tom Ford and Michael Kors quickly followed with similar announcements.

Why did it take big brands no time at all to adapt to such a revolutionary and seemingly innovative change? How could it be that a tried and tested system can so suddenly be switched to accommodate immediate retailing instead of operating on wholesale orders?

It is partly a symptom of a fashion industry looking for a new identity, influenced as it is by social networks and the public’s increasing interest at being included in the conversation, but it also underlines that fact that, for such big fashion houses, switching from wholesale to retail is actually quite easy, and it won’t change much in terms of their overall operations.

The truth is that their supply chain is ready for it; their structure can manage any speed at this point. Their gigantic, well-oiled but profoundly inefficient machine is already geared to speed – time to market is getting faster and faster and reaching consumers directly is now seen as the way forward.

On one level, it fits with the trend for seasonless collections as it reiterates the point that we have too many seasons in the fashion calendar (couture, ready to wear, men’s, women’s, autumn/winter, spring/summer, pre-collections, resort…), and as such it was quickly labelled as triumphantly ‘innovative’, ‘game-changing’, even ‘genius’.

The reality is a bit more sinister, and what it actually means, or implies, is supremacy of the big over the small. Because for a small brand, for an emerging designer, or anyone who isn’t supported by an enormous, invisible supply chain, this change will be almost impossible to follow.

There is no way that a small brand or unknown young designer can predict the amount of orders they will receive, or what will be the best seller of the season; a small brand relies on their buyers viewing the collection and giving potentially useful feedback. A buyer will take time to consider what will and won’t work in their boutique, thus influencing a flux of minimal changes that can still occur between orders being placed and production, becoming part of a conversation that leads to better understanding and further development.

I have seen young designers’ collections being finished only minutes before the show: a final adjustment to the length of a sleeve, adding an embellishment, re-introducing a piece that is more experimental and somewhat unfinished and wasn’t part of the original merchandising but looks good in the final line-up.

And after a collection is exhibited (and the young designer will often travel around several fashion weeks to showcase it) comes another process, that of producing it according to how many orders have been received.

The production process is an integral and vital aspect of learning, as it means working with other people. The pattern cutter will still be tweaking; the designer will visit the production studio, often meeting the seamstresses (or skyping with them if they are abroad). While waiting for fabrics to be delivered in full, they are in contact with the industry that supplies them – it’s when they know for sure that blue sold better than brown, or the tweed was more popular than the twill.

It is the moment when everybody across the supply chain holds hands. It’s a time of union, where triumphs and losses are shared. If the collection sold well, it’s an honour as well as guaranteed employment for the people who make the clothes, and they will be a part of the designer’s pride and success. It’s when one really understands what it is like to be a fashion designer – what the industry behind their collections looks like. It’s getting to know the people to whom they are linked by the thread that is clothes-making, and the techniques that make those makers unique.

It takes time.

Which is precisely what has now been almost eradicated from the fashion language, in one carefully orchestrated statement.

From fast to faster.

It is as if the concept of time in fashion can only be about narrative references to the past, like the ‘70s look, or the ‘90s throwback and no longer about the precious time it actually takes to make great clothes that are considerate and well made.

Interestingly, Raf Simons cited speed and lack of time for the creative process as one of his main reasons for leaving Dior, and Alber Elbaz echoed that sentiment when leaving Lanvin.

The only genius thing about the murder of time is in its irony: this is the high end imitating the high street, making Topshop and H&M look like the visionaries that they actually were.

Because, make no mistake, this move confirms that fast fashion and fast luxury have won the battle, at least temporarily.

But there is hope.

The fact is that the fashion industry as we know it now is relatively new, and it’s still finding its feet: which is why the movement to make it sustainable at its core is so important. If we act now to make it right while it’s in its infancy, we stand a real chance to grow it into a positive force, all things considered.

To continue to grow Fashion Revolution as a global movement for change, we need your financial support. Even the smallest donation will help us to continue delivering the resources we need to run our revolution. Please donate, be a part of this movement and help us keep going from strength to strength. We can, if you help.

Ding (left) explains his life philosophy to researcher Mikaela Kvan (right) stating, “I will work until I can’t. That is how I will live my life.” Photo by Daniel Huang

Shenzhen developed earlier than other cities in China so there were many more opportunities to find work here when I first arrived. I came here along with other migrant workers. I didn’t think I would stay here for long but it ended up being 20 years. I have been in Shenzhen for 22 years. Before I married, and when I was young, I lived in cities all across China. I am originally from Jin Jiang in China’s northeastern Jiang Su Province. I go home once a year for the Spring Festival.

I work in garment factories pressing clothes before they are packed for distribution. I’ve had this job on and off over the course of my life. My very first job was as a presser. Soon after, I graduated to a managerial position doing logistics for 20 years. Now I am back to my old job. It’s harder but I have more flexibility and less pressure.

My wife doesn’t live here with me. We used to live together but, when our daughter started junior high school, my wife left to be with her. Our daughter’s teacher called to tell us she was not doing well in school. As parents we want our kids to have a better life than we do and we want them to achieve something. I don’t want her to end up doing physical labor like us.

Now our daughter is 28th in her faculty at university. I am relieved to see her doing so well. She is a good kid and I am proud of her. She studies information engineering at Nanjing University. I’m not sure what her future holds, because it is up to her. She may not be able to make a lot of money because getting rich partly depends on luck.

Earlier this year she was selected as one of ten students to study abroad in America. There was a test to select those ten students. Those who aced the test could go. The school will pay for half of the expenses and we will cover the other half. So far, my wife and I can afford it. We are a bit strapped for cash, but I haven’t worked excessively because health is also important to me. If there are orders coming into the factory and us workers have the opportunity for lots of overtime then I can just stay here. However, if there is no overtime at this factory then I will go to other factories to do the same work. I just don’t take any days off. That includes Sunday. I see a bit of myself in my daughter. She is hardworking.

The reason I stay so disciplined in my work is my child. I want to provide for her. I believe you can do anything you want as long as you have money, but you can’t do anything without money. When my kid finds a job, builds her own family and everything is settled for her, only then will I go back to my hometown. I’ll find a job there so my kid doesn’t have to support me. I don’t want to burden her and I want to lift some pressure from her shoulders. I will work until I can’t. That is how I will live my life.

This interview has been edited. It was originally conducted on July 13, 2014, in Yantian, an industrial area east of Shenzhen, China. Read the full story here

Primary Voice is a collection of primary source interviews dedicated to documenting the living stories of garment factory workers worldwide. It was created by urbanist Mikaela Kvan. To read more interviews and to get in touch visit www.primaryvoice.org

Channa needs to spend over 300USD per month on food to feed her four children, chronically ill elder sister, husband and herself. Photo by Sok Chanrado

I’ve lived in Phnom Penh since 1992. My hometown is in Prey Veng Province. Where I used to live in the countryside, it would flood every year. I couldn’t find food to eat and I was an orphan. I moved to Phnom Penh to live with my sister so that I could work at a factory to feed myself. Phnom Penh had and still does have many more job opportunities than my hometown. I like living here for that reason.

The things I value most in life are having enough food to eat, and living together with my children and husband. I want to be able to send my kids to school everyday but financially I can’t. Simply speaking, when you don’t have money you cannot do anything. If I want my kids to go to school I have to look after my younger daughters, but then I can’t go to work.

My husband is a construction worker. Both of our wages combined are not enough to live off of. Plus, I have another mouth to feed – my elder sister. When her health is good, she will help out by taking care of my younger kids. If she doesn’t feel well, my elder sons must take care of their sisters and cannot go to school.

Despite our best efforts, things haven’t worked out the way we wanted. For example, in 2012, when my youngest daughter was born I couldn’t work and I didn’t have anything to eat. I had a big fight with my husband. It’s normal for a couple that lives together to argue often. After our fight one of my friends asked me to move to the border of Cambodia near Thailand but I didn’t go. I decided to go to an orphanage to ask for a place to stay instead. They did not let us stay. I didn’t know what to do, so I sold all of my stuff from living in Phnom Penh. If you can’t work you can’t live. I thought if we were in the provinces people would help us out so we moved to Sompov Loun for about five or six months. But then my kids became allergic to the land there. I didn’t know what to do. I asked another orphanage to let my kids learn at their school but my kids weren’t accepted because they weren’t orphans.

In my opinion, if your kids are educated they will think about and respect you as a mother. I have seen kids on my block beat their moms, cursing them. Kids nowadays have no manners or respect whatsoever. I hope and believe my kids, whether they are educated or not, will think about me as a mother and I can depend on them in the future. If they are educated though, I believe I can depend on them more. My 14 year-old son is a good kid. He does house chores, looks after his sisters and listens and obeys well unlike rich kids his age. I think a kid from a humble family is better than a rich kid in terms of character.

I believe my kids would have a bright future if they could go to school regularly though I cannot afford for them to do so. Think about it. I have to spend 10,000 KHR (10 USD) – and it’s not that small of an amount – everyday for food. So my monthly expenses for food is 300,000 KHR (300 USD). Not to mention, I have to pay for rice, utilities, rent, and so on. If I let my kids go to school regularly, I cannot make it at the end of the month.

My kids want to learn English, but I cannot let them. All I can do is buy a book for them to learn at home. I asked the teacher whether my kids were smart in school and they said my kids were the best. Both of my sons are the best. It’s my sin from my past life that I cannot afford for my kids to go to school. But unlike other mothers who do not care about their kids’ progress in school, when I get home from work, I always ask my kids what they learned that day. Since I have no inheritance for them, as a mother, that’s all I can do for them.

I think about my life all the time. My mother passed away when I was young, just six months after giving birth to my younger sister. I thought I would never get married if I couldn’t make enough money. We came to Phnom Penh after I reached puberty and my sister was a bit bigger. Our financial situation was better because my sister was working. But then I got my first abortion and got married. After that, my father died and my older sibling sold our land. That was when I had another abortion, my third child. We’ve been poor since then. I’ve been praying to god asking for help but nothing happens.

Yesterday or the day before yesterday, the school called for a parent-teacher conference. I went and they asked why my kids have stopped coming to school. I told them it was because I was poor. And then they asked why I became a parent if I had no ability to raise a child. I replied, “What was I supposed to do? I tried my best but it didn’t work out. Should I just rob or steal to make it happen?”

For example, when he gets his paycheck, he knows I need the money, but he only gives me some. You know men nowadays; needless to say, they are…tears come to my eye when I try to talk about this. My sister lives with us and he’s not happy about it. That is why he always picks fights with me. He is also younger than me. He’s still young and beautiful. That’s why. He loves his kids though. He hangs out a lot outside with his friends and stuff, so he always finds faults in me, but he never beats me.

I had a fiancé who was a widower before I met my husband. My husband worked on the construction near my factory. One day he asked me for some water. Then he touched my hand and I was like, “Why are you so rude? You don’t even know me.” After that, he followed me around and came to my house to ask for my hand in marriage. At that time, my late father was still alive so he advised me to think it over between a bachelor and a widower. He said it was better to live with a bachelor. Since I didn’t love either of them, I just followed my father’s advice and got married to my current husband. But it was only ten short years of happiness. After my first abortion, ten years later, things got rough.

The way I see it, if your parents are alive you dare not refuse their advice or complain. If you follow your parent’s advice you will blame them for your unhappiness. However, that is not the case for me. All I can do is be regretful and accept this decision as a sin from a previous life. If my father were alive, I would blame him as well for his misjudgment. I just feel sorry for myself. My life is an endless sad story. I don’t want to talk about it anymore.

This interview has been edited. It was conducted in two parts. The first took place on August 4, 2014. at the shoe factory where Channa was worked. The second time we met was on August 9, 2014, at the apartment complex where she lives on the outskirts of Phnom Penh, Cambodia. She quit her job at the shoe factory. You can read the original interview here

Primary Voice is a collection of primary source interviews dedicated to documenting the living stories of garment factory workers worldwide. It was created by urbanist Mikaela Kvan. To read more interviews and to get in touch visit www.primaryvoice.org.

22-year-old Huang has been working in garment factories for about five years. Photo by Daniel Huang

I have been working in garment factories for four or five years. I am 22 years old now. When I graduated from junior high school I had nothing to do. Someone told me how good making clothes was and they introduced me to the industry. At that time I thought I was young so it would be good to learn something new. I started to make clothes then and I still do now.

I had many dreams when I was little, such as being a doctor or a policewoman or even being rich. I was so naïve then. Take the doctor dream for example. I am so scared of seeing blood. I once saw someone’s injury from a car accident. OMG, it was terrible. I couldn’t even look at the wound, let alone touch it. I even saw a dead body once. How can I be a doctor if I am so afraid of blood, injuries and death?

My plan is to work at the garment factory for a few more years but I won’t do it for the rest of my life. I will go back to my hometown to open a store in a few years. I just want to open a store, but I don’t know what kind yet.

When I graduated from junior high school, my mom asked me to keep studying but I didn’t. I was in a dilemma. My mom didn’t want me to work in the city at such a young age. She wanted me to stay in school but I was rebellious. I didn’t do well in school so I thought, “Why bother studying and spending money on my education?” I just came to the city to work so I could support myself. It was a very difficult decision for me. My mom tried to force me to study but I wouldn’t go. Honestly, I regret the decision a bit. I should have gone back to school.

For girls, it is better to learn something not so tough. I think I would learn to make patterns for clothes or something using electronic devices if I could go back to school. I want to learn something easy because I am a lazy person. I like doing finishing work for others so I don’t have to make everything from the beginning.

In terms of social life, garment factory workers like us don’t have time to take a break because we need to do overtime to keep up with production. I go out on public holidays, but there are so many people and cars during that time. I remember I went to a museum park once and I waited in line to get in from 7am to 10 am at the entrance. There were so many people there. For me, having a social life means going out shopping. Girls like shopping and buying cosmetic products. We should spoil ourselves from time to time.

For example, I once spent 2000 RMB (330 USD) to buy a set of Mary Kay products. It is a big brand that I can trust. I buy skin care products instead of make-up. It is important for me to take good care of my skin to look young and pretty because there is dirt and dust around the factory. When I first came to the city, my skin was dark but my skin is getting better with good care. I think it is better to take care of my skin as I grow older. Dirt around the factory may clog the pores in my skin and cause various skin problems. To help, I give myself facials.

Concerning other self-care, I rarely exercise. Firstly, I don’t have much time and secondly, I am too lazy. I will sleep late whenever I have a day off. I am so lazy that I miss the time to exercise. I also hate to wash my clothes because I am lazy. I think it’s best if there is a washing machine but there is no machine so I just wash the clothes myself. When I finish my shower at night, how I wish someone would wash my clothes and I could just lie in bed and play with my phone. But no one is there to help me. Even if I forget about them for half a month, I still have to wash them myself.

This interview has been edited. It was conducted on July 13, 2014 at the factory where Huang works in the industrial area of Yantian east of Shenzhen, China. You can read the original interview here

Primary Voice is a collection of primary source interviews dedicated to documenting the living stories of garment factory workers worldwide. It was created by urbanist Mikaela Kvan. To read more interviews and to get in touch visit www.primaryvoice.org

Matt is a 28-year-old garment worker in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Photo by Sok Chanrado

I’ve been working in garment factories since 2004. It’s been ten years. During those years, a lot in my life has changed. I used to live with my aunt before I started working so I would do all of the chores around her house. Now that I earn my own income I can afford to buy whatever I want and I can help my younger siblings go to school. I have two sisters and one brother. I am 28, my brother is 26, the third is 24, and the last one is 19 years old. My two younger sisters also work in garment factories but our brother goes to university.

I had a rough childhood so I want to forget about it. When I was young I sold things in the market like fish and meat. I sold anything I could. I would sell things for other people, too, in order to save for my siblings and me to go to school. We lived in Sihanoukville then and my family was poor. All of my siblings had to work to earn money for school at the age of seven or eight. In 2004, my mom passed away. That’s when I quit school.

My father was a drunk. He always caused problems – swore at us or threw things around the house or kicked us out. Because of his abuse I decided to bring my siblings to Phnom Penh to live with our aunt. After living with her for about 4 months we had to rent our own house. The financial burden was too much for her.

When I was a child I dreamt that I would finish school and get a good job that could support my family and me. When my mother died I had to quit school to work because I am the oldest sibling. I was only in fifth grade. I felt such pity for myself after quitting school. Ultimately, I had no choice. Time wouldn’t stop. I had to look forward and take care of my siblings.

I must sacrifice myself for their sake. It hasn’t been easy. At times I feel really irritated and stressed but when my siblings behave themselves, and don’t give me a hard time, I feel my capabilities are limitless. Even if we don’t have parents, we still have each other. As the eldest sibling I feel a great responsibility to be a good role model for my brother and sisters.

Financially, we can only depend on ourselves. Unlike others whose parents are still alive, we can’t survive without working. I don’t have the luxury of living that way. If it were up to me I would not work in a garment factory. I want to open a small shop where I have the potential to earn income daily. With my current job, I have to wait until the end of the month to get a paycheck from the factory. By that time, I need to pay rent and it seems I have nothing left. Unfortunately, I don’t have the ability to realize this dream for myself right now because I need to support my brother who is in university. Once he graduates I could probably quit my job at the garment factory and open my own shop. I’m optimistic about my future. When my siblings were young, I worried they wouldn’t listen to me. But it turns out my siblings are good kids. I hope the future will be easier. Since I am having a hard time for their sake now, I believe they will think about me when they have jobs.

This interview has been edited. It was conducted on August 10, 2014, outside Matt’s room in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. You can read the original interview here

Primary Voice is a collection of primary source interviews dedicated to documenting the living stories of garment factory workers worldwide. It was created by urbanist Mikaela Kvan. To read more interviews and to get in touch visit www.primaryvoice.org

I woke up at 5, just like every morning. It is getting light by then and the birds have been singing for a while. I put some water on the fire, a bigger pot for washing, and a smaller pot for cooking nsima, our local breakfast, for my youngest children. Aged 6 and 13, their appetite is the only thing that gets them out of bed! Within the next hour, everyone is washed and fed and ready for the day. The little one is off to primary school, a mile walk away, and the older one goes to secondary school a little further on. I have 4 other children, so 6 in total and I look after my elderly mother who lives with us.

School fees and life expenses are high and I would not be able to pay them if it wasn’t for my job.

What do I do?

I am the main cutter at Mayamiko, a fashion workshop which also has a training centre for the local community. It is still tough to get by, but what a change from two years ago!

I had learned from a friend that the Mayamiko project had moved in the area. I had no skills, but I was in real need for some money to pay school fees. My seasonal work selling beans was not enough and we were skipping meals. The younger children were falling asleep at school because of hunger. Their teacher told me.

So I trusted in God and I knocked on the door and asked if they had any casual work. And the answer was yes. For a few months I helped the team keep the workshop tidy and wash and iron fabric, and I observed the tailors, cutters and production managers. Every time training was on I would listen in as much as I could. I could hand sew and I was allowed to bring in the kids clothes and fix them using the machines, and I could also collect the very small pieces of scraps.

When the application for the new training round opened 6 months later, I asked if I was allowed to apply. To show how keen I was, I brought in a teddy bear and a door mat I had hand sewn with the small bits of fabrics I had been collecting. I could not believe it when after a few weeks I was offered a place in the Mayamiko training programme. I studied for 6 months with a small group of 5 women, we each had our sewing machine and a wonderful teacher, Charity. We got to eat together with the professional tailors every day, exchanging stories, experiences and tips. We got additional training on how to manage money, budget and plan to help us prepare for life after training. I had not learnt this before, so this was very helpful.

At the end of the course, we got an option to save some money and get a grant to buy a sewing machine. I had started making kids dresses to sell to help me save through our saving scheme organised by Mayamiko, and one day I went to the workshop to bring in some of my savings, and the best thing happened.

Paola, our founder was there, and I was asked to join an apprenticeship to become a professional cutter. Charity, who had been my trainer, had been promoted to main cutter, but was due to go on maternity leave in 5 months time and I had the chance to work towards covering for her while she was away. This meant I was to learn how to cut fabric in different sizes and shapes from a paper pattern. Cutting is very important because if you don’t cut well, it is very hard for tailors to sew well, and you can ruin a garment so easily. You have to be very careful and I have a big responsibility to my team when I cut.

I was so excited and worried at the same time. The workshop produces clothes and accessories for the Mayamiko brand which is sent out of Malawi and women all over the world buy and wear, so everything has to be perfect! I worked hard every day, for 8 hours. Having lunch together with everyone else really helped, so I could have a chat and a laugh and relax a little. And not worry about going hungry all day for it is hard to work on an empty stomach. I also got a chance to ask questions and understand more about how it all worked. It was the first time in my life I had a salary at the end of the month, and I knew exactly how much I was going to earn, and thanks to the financial training I could budget and prioritize.

After my apprenticeship I was told I was successful and Mayamiko offered me a full time job.

I now have a higher salary, paid sick leave, paid holidays and Mayamiko alsopays into the government pension scheme as well as a gratuity scheme, which is another way of helping us save.

It is more than a dream that I now have the safety of a monthly income and if I do my job well, I can keep growing and maybe I can also train to become a tailor. That would give me more skills for the future. I would also like to learn English better.

What makes me the happiest is that I can ensure my children and grandchildren have an education, and never have to go hungry. Because with an education they can choose what they want to become in life, all doors are open, and if they fail they only have themselves to blame.

So now it is time for my daily walk to the Mayamiko workshop. It takes me about 45 minutes and I use the time to pray and give thanks, and think about the day ahead. We are in between collections so today I am cutting some lounge shorts to go with our organic cotton T-shirts. They are a bit like pyjamas but you can also wear them for other things like relaxing and walking around the house or the garden, and reading.

And I have been given a challenge to be creative and cut some small animal shapes with our scraps, we don’t like wasting anything. We’ll use them to decorate wash bags and shoppers. We call ourselves a ‘Zero Waste’ workshop and believe me, we find a use for everything!

Every day is a bit different at Mayamiko, and we are all like a family. Sometimes we don’t get on, but we really care for each other.

Do I like the clothes we make for women all over the world? Some of them I love, some of them are a bit unusual for me.

But I love the fabrics that we choose. The dress I am wearing in this picture is made using some left over fabrics at the workshop. I made it myself. Do you like it?

You can also watch this short video about the making of of some of our pieces.

Find out more about Mayamiko, and the vision of our founder, Paola Masperi, of #changinglives and #nurturingtalents and browse our pieces here: www.mayamiko.com

Information about our charity, The Mayamiko Trust can be found here: http://www.mayamiko.org/ For more information please contact: info@mayamiko.com

Our social media handles are:

https://www.instagram.com/mayamikodesigned/

https://twitter.com/Mayamiko_

https://twitter.com/MayamikoTrust

https://www.facebook.com/MayamikoTheLabel

https://www.facebook.com/MayamikoTrust/

It still strikes me as profoundly wrong that even though cotton is the world’s oldest commercial crop and one of the most important fibre crops in the global textile industry, the industry generally fails to focus on the entire value chain to ensure that those who grow their cotton also receive a living income.

Up to 100 million smallholder farmers in more than 100 countries worldwide depend on cotton for their income. They are at the very end of the supply chain, largely invisible and without a voice, ignored by an industry that depends on their cotton.

When it comes to clothing, companies’ supply chain engagement was once limited to who their importer was. Now they are engaging with their supply chain more and have better awareness of the factories used to manufacture their end products. Even before the Rana Plaza disaster of 2013, there had been increased attention on improving the conditions experienced by textile factory workers thanks to campaigns such as the Clean Clothes Campaign.

Some companies also have awareness beyond the factories and these are all movements in the right direction. However, even those mindful of the difficulties faced by factory workers, tend to miss the first links in the supply chain.

Maybe this is because cotton farmers continue to somehow lose out in both the so-called ‘sustainable’ and ‘ethical’ fashion debates. When companies talk about ‘sustainability’ in their clothing supply chains, they are generally looking at the environmental impact of sourcing the raw materials. Meanwhile in ‘ethical’ conversations about the many livelihoods touched by the garment value chain, companies generally refer to factory workers, again overlooking the farmer who grows the seed cotton that goes into our clothing.

The reason we need to keep insisting that cotton farmers are an important part of the fashion supply chain is because cotton is failing to provide a sustainable and profitable livelihood for the millions of smallholders who grow the seed cotton the textile industry depends on. Just as it’s important for us to take home a living wage, to help bring a level of security for our families and the ability to plan for the future, I would argue that this is even more vital for people living in poorer countries where there is little provision for basic services such as health and education or the safety net of social security systems to fall back on.

As a global commodity, cotton plays a major role in the economic and social development of emerging economies and newly industrialised countries. It is an especially important source of employment and income within West and Central Africa, India and Pakistan.

Many cotton farmers live below the poverty line and are dependent on the middle men or ginners who buy their cotton, often at prices below the cost of production. And rising costs of production, fluctuating market prices, decreasing yields and climate change are daily challenges, along with food price inflation and food insecurity. These factors also affect farmers’ ability to provide decent wages and conditions to the casual workers they employ. In West Africa, a cotton farmer’s typical smallholding of 2-5 hectares provides the essential income for basic needs such as food, healthcare, school fees and tools. A small fall in cotton prices can have serious implications for a farmer’s ability to meet these needs. In India many farmers are seriously indebted because of the high interest loans needed to purchase fertilisers and other farm inputs. Unstable, inadequate incomes perpetuate the situation in which farmers lack the finances to invest in the infrastructure, training and tools needed to improve their livelihoods.

However research shows that a small increase in the seed cotton price would significantly improve the livelihood of cotton farmers but with little impact on retail prices. Depending on the amount of cotton used and the processing needed, the cost of raw cotton makes up a small share of the retail price, not exceeding 10 percent. This is because a textile product’s price includes added value in the various processing and manufacturing activities along the supply chain. So a 10 percent increase in the seed cotton price would only result in a one percent or less increase in the retail price – a negligible amount given that retailers often receive more than half of the final retail price of the cotton finished products.

Within sustainable cotton programmes, Fairtrade works with vulnerable producers in developing countries to secure market access and better terms of trade for farmers and workers so they can provide for themselves and their families.

Our belief is that people are increasingly concerned about where their clothes come from. This year we visited cotton farmers in Pratibha-Vasudha, India, a Fairtrade co-operative in Madhya Pradesh. We saw the safety net that Fairtrade brings; the promise of a minimum price that works in a global environment. The impact on prices of subsidised production in China and the US adds to unstable global cotton prices. These farmers democratically decide how the Fairtrade Premium is spent: on training to improve soil and productivity, strategies to mitigate the impacts of climate change and on the most important ways for their communities to benefit, such as building health centres and educating children.

Consumers want their clothes made well and ethically, without harmful agrochemicals and exploitation. We think about farmers when we talk about food. Let’s start thinking about farmers when we think about clothing too.

Image credits: Trevor Leighton.