By Allison Griffin for Remake

Few things are more powerful than a room full of women who have something to say.

As part of our Remake Journey we traveled 2 hours outside of Phnom Penh along dirt roads to a small school in the middle of rice fields, one of the few safe places makers are able to unite to talk about their rights without the police breaking up the meeting.

This gathering was hosted by Solidarity Center, to help makers fight for their rights. We learned that when big factories agree to cheap prices and tight deadlines, they often can’t meet these demands. So they ship orders off to fly by night operations–dark, dingy subcontracted factories where the conditions are the worst.

The women we met had sneaked out labels from the brands they illegally sew for including Zara, H&M and Tommy Hilfiger. It was dangerous for them to sneak these photos and labels out but they did it anyway, in the hope that we and you as readers would help them, to ask these brands pressing questions about why they worked such long hours for so little.

I had the honor of sitting down with one such maker, Char Wong. This is her story:

I grew up in a family of eight children raised by a single mother. I was a farmer before working in a subcontracted garment factory. I found work in a subcontracting factory to earn more money and provide a better life for my own family, but the pressure from the daily quotas is stressful and the money is not enough.

I support my 16-year-old son, 10-year-old daughter, my elderly mother, along with my husband who is a farmer. I struggle to feed everyone with the minimum wage and extra $2.50 a day that I earn. My mother has diabetes and her medicine costs $30 a month, over 20 percent of my monthly income. I also want to save money for my children’s education.

wanted a better life for myself and my family which is why I took this work. But life has become harder. I get paid per 12 pieces, but if there’s even one single error in the batch, I don’t get paid at all.

A few years ago, the factory would receive an order for a new design every two or three months, but with the new fast fashion cycles, it now gets more and more new designs in a shorter amount of time. Learning complex designs is very difficult and we get no training. Sometimes it takes two or three hours just to learn and the factory supervisor scolds us for any mistakes. The more time it takes to learn a design, the less time I have to meet the quota and the less money I make. I typically make $5 a day, but with the more complex designs, I only make $2 a day.

Sometimes I cry because I fear I won’t meet the quota and get paid.

Like most parents from all corners of the world, I want a better future for my two children. I hope to pay for their college education so that they can work in Cambodia’s government. Government jobs pay well and do not require hard physical labor. I hope that my children can be government leaders and help improve the conditions and rights of future garment factory makers, just like myself.

I am grateful for organizations like the Solidarity Center, who teach us about our rights. I am learning to speak up more. I want my story and my colleagues’ stories to spread to people throughout the world.

You being here, listening, makes me hopeful.

I definitely felt a lot of girl power throughout the day, both from our own all female crew and the makers we met. These women are not playing victims, but fighting for their rights and educating themselves on their rights. Speaking with Char Wong, I realized that the hopes she has are fundamentally no different from mine–for a fulfilling life. I hope as a designer, I can be a part of the change and that this story moves you to buy better. Together we can #remakeourworld.

Just before the onset of New York Fashion Week, Burberry announced a radical shift in how their collections will be shown and sold: no longer following the usual fashion schedule of two menswear and two womenswear seasonal shows, but instead amalgamating them into two gargantuan annual shows and, crucially, making the collections available to buy immediately, eliminating the concept of ‘previewing’ to buyers before the clothes are made available to the customer.

Within a few days, Tom Ford and Michael Kors quickly followed with similar announcements.

Why did it take big brands no time at all to adapt to such a revolutionary and seemingly innovative change? How could it be that a tried and tested system can so suddenly be switched to accommodate immediate retailing instead of operating on wholesale orders?

It is partly a symptom of a fashion industry looking for a new identity, influenced as it is by social networks and the public’s increasing interest at being included in the conversation, but it also underlines that fact that, for such big fashion houses, switching from wholesale to retail is actually quite easy, and it won’t change much in terms of their overall operations.

The truth is that their supply chain is ready for it; their structure can manage any speed at this point. Their gigantic, well-oiled but profoundly inefficient machine is already geared to speed – time to market is getting faster and faster and reaching consumers directly is now seen as the way forward.

On one level, it fits with the trend for seasonless collections as it reiterates the point that we have too many seasons in the fashion calendar (couture, ready to wear, men’s, women’s, autumn/winter, spring/summer, pre-collections, resort…), and as such it was quickly labelled as triumphantly ‘innovative’, ‘game-changing’, even ‘genius’.

The reality is a bit more sinister, and what it actually means, or implies, is supremacy of the big over the small. Because for a small brand, for an emerging designer, or anyone who isn’t supported by an enormous, invisible supply chain, this change will be almost impossible to follow.

There is no way that a small brand or unknown young designer can predict the amount of orders they will receive, or what will be the best seller of the season; a small brand relies on their buyers viewing the collection and giving potentially useful feedback. A buyer will take time to consider what will and won’t work in their boutique, thus influencing a flux of minimal changes that can still occur between orders being placed and production, becoming part of a conversation that leads to better understanding and further development.

I have seen young designers’ collections being finished only minutes before the show: a final adjustment to the length of a sleeve, adding an embellishment, re-introducing a piece that is more experimental and somewhat unfinished and wasn’t part of the original merchandising but looks good in the final line-up.

And after a collection is exhibited (and the young designer will often travel around several fashion weeks to showcase it) comes another process, that of producing it according to how many orders have been received.

The production process is an integral and vital aspect of learning, as it means working with other people. The pattern cutter will still be tweaking; the designer will visit the production studio, often meeting the seamstresses (or skyping with them if they are abroad). While waiting for fabrics to be delivered in full, they are in contact with the industry that supplies them – it’s when they know for sure that blue sold better than brown, or the tweed was more popular than the twill.

It is the moment when everybody across the supply chain holds hands. It’s a time of union, where triumphs and losses are shared. If the collection sold well, it’s an honour as well as guaranteed employment for the people who make the clothes, and they will be a part of the designer’s pride and success. It’s when one really understands what it is like to be a fashion designer – what the industry behind their collections looks like. It’s getting to know the people to whom they are linked by the thread that is clothes-making, and the techniques that make those makers unique.

It takes time.

Which is precisely what has now been almost eradicated from the fashion language, in one carefully orchestrated statement.

From fast to faster.

It is as if the concept of time in fashion can only be about narrative references to the past, like the ‘70s look, or the ‘90s throwback and no longer about the precious time it actually takes to make great clothes that are considerate and well made.

Interestingly, Raf Simons cited speed and lack of time for the creative process as one of his main reasons for leaving Dior, and Alber Elbaz echoed that sentiment when leaving Lanvin.

The only genius thing about the murder of time is in its irony: this is the high end imitating the high street, making Topshop and H&M look like the visionaries that they actually were.

Because, make no mistake, this move confirms that fast fashion and fast luxury have won the battle, at least temporarily.

But there is hope.

The fact is that the fashion industry as we know it now is relatively new, and it’s still finding its feet: which is why the movement to make it sustainable at its core is so important. If we act now to make it right while it’s in its infancy, we stand a real chance to grow it into a positive force, all things considered.

To continue to grow Fashion Revolution as a global movement for change, we need your financial support. Even the smallest donation will help us to continue delivering the resources we need to run our revolution. Please donate, be a part of this movement and help us keep going from strength to strength. We can, if you help.

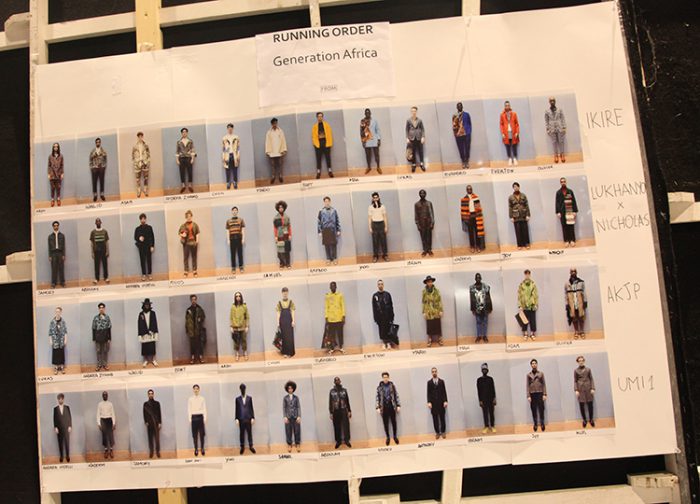

Yesterday at Pitti Immagine Uomo 89 in Florence, the Fondazione Pitti Discovery and ITC Ethical Fashion Initiative held a runway show “Generation Africa”. With a focus on fashion from Africa, this unique platform promoted young and talented fashion designers from the continent, and showed the energy of today’s African creative scene.

“Generation Africa is the chance to open a new window on one of today‘s most creative scenes” says Lapo Cianchi, head of Special Projects at Pitti Immagine

The show featured four brands already known on the international market that present different facets of the African continent and who focus on manufacturing in their home countries. AKJP, Ikiré Jones, Lukhanyo Mdinigi x Nicholas Coutts and U.Mi-1 all presented their Autumn/Winter 2016-17 men’s collections.

“We continue our collaboration with Pitti Immagine to showcase the creativity of Africa. We want to convey a different image of the continent, one of innovation and diversity with a strong youthful energy for positive change. Pitti Uomo is the perfect platform for the designers to express their vision and show that Africa means serious business.” says Simone Cipriani, Head and Founder of the ITC Ethical Fashion Initiative.

For Generation Africa, the Ethical Fashion Initiative partnered with the Italian association, Lai-momo which welcomes asylum-seekers in Italy and promotes cross-cultural exchanges between Africa and Europe with the aim of reducing stereotypes and preconceptions. As part of a joint effort by EFI, Lai-momo and Pitti Immagine to raise awareness on migration, three asylum seekers modelled for the show, giving them an opportunity to earn a wage and be part of an empowering international event celebrating creativity from Africa. Continuously striving to improve diversity in the fashion industry, the Ethical Fashion Initiative aims to demonstrate fashion’s capacity to support the betterment of society.

The Ethical Fashion Initiative is a flagship programme of the International Trade Centre, a joint agency of the United Nations and the World Trade Organization. The Ethical Fashion Initiative links the world’s top fashion talents to marginalised artisans – the majority of them women – in East and West Africa, Haiti and the West Bank. The Initiative has been connecting artisans to the global fashion supply chain since 2009. The Ethical Fashion Initiative also works with the rising generation of fashion talent from Africa, encouraging the forging of fulfilling creative collaborations with artisans on the continent. Under its slogan, “Not Charity, Just Work” the Ethical Fashion Initiative advocates a fairer global fashion industry.

The four participating brands were:

AKJP // Keith Henning & Jody Paulsen, South Africa

AKJP (Adriaan Kuiters + Jody Paulsen) is a menswear and womenswear brand founded by South African designer duo, Keith Henning and Jody Paulsen. AKJP‘s signature is its artful contemporary twist on classic and utilitarian menswear. The development of strong prints and sports-inspired motifs for each collection has become core to AKJP. AKJP uses layering, boxy silhouettes and asymmetrical detailing as a signature styling feature. AKJP has been recognised as one of South Africa’s most innovative brands, bringing contemporary and cool to the South African fashion landscape. In 2015, AKJP was one of the finalists at Vogue Italia’s Who Is On Next? Dubai.

IKIRÉ JONES // Walé Oyéjidé, USA & Nigeria

Ikiré Jones (pronounced “E-kee-rae Jones”) is a menswear company that marries African aesthetics with classic art from all over the world. Each of the brand’s pieces tells a contemporary story by using historical artwork as a medium for modern expression. With every collection, the brand places a strong emphasis on societal issues that affect immigrant and transient populations across the globe. Importantly, Ikiré Jones seeks to properly introduce modern African culture to the world. Through clothing, Ikiré Jones seeks to weave together a tighter global community. The brand’s tailoring is done in the United States, and its accessories are printed and hand-rolled in Macclesfield, United Kingdom.

LUKHANYO MDINGI x NICHOLAS COUTTS // Lukhanyo Mdingi & Nicholas Coutts, South Africa

South African designers Lukhanyo Mdingi and Nicholas Coutts collaborate on this Autumn/Winter 2016-17 collection to illuminate each other’s aesthetics. The design partnership combines Mdingi’s minimalist approach with Coutts’ distinctive signature weaving style. Together, the designers create a menswear collection that embodies strength, empowerment and contemporary sophistication.

Lukhanyo Mdingi interprets minimal aesthetics with his clothing, finding the balance between line, form and texture. Mdingi creates minimal looks that are distinct and powerful, with a flare of contemporary elegance and sophistication. Nicholas Coutts’ signature is creating garments that are textured and uses fabrication to create a pleasing contrasting visual. Influenced by the Arts & Crafts movement, Coutts specialises in using handwoven fabrics and hand knitted items.

U.Mi-1 // Gozi Ochonogor, Nigeria & UK

U.Mi-1 (pronounced you.me.one) is a contemporary brand for the modern cool man. It tells a different side of the African fashion story with collections inspired by Nigerian culture, architecture and art. Headed by Nigerian designer Gozi Ochonogor who calls London, Tokyo and Lagos her homes, U.Mi-1 collections are a blend of British tailoring aesthetic with the hallmark of Japanese artisanship and African spirit, delivering innovative designs and quality. Best described as tailoring with a twist, U.Mi-1 focuses on style, comfort and quality with interesting detailing that the wearer discovers anew.

Burkina Faso is the biggest African cotton producer and exporter, so it is no surprise that it boasts a strong textile heritage of handwoven cotton fabric, traditionally called Danfani. Stripes are the signature style of handwoven Burkinabé fabric however artisans are able to weave complex tartan and hounds-tooth fabric designs. Preparing the design on the loom itself can involve three to seven days of work depending on the complexity of the design. Artisans can weave on small and wide looms, the latter makes the fabric more attractive commercially as fashion & design buyers can do more with this larger fabric.

In Burkina Faso, the Ethical Fashion Initiative has worked to create a cooperative which links up several weaving ateliers. The introduction of wide looms and financing of capacity building workshops has also been central to the Ethical Fashion Initiative’s work of bringing brands like Stella Jean, United Arrows and Vivienne Westwood to work with artisans in this area of the world.

In this video, Italo-Haitian fashion designer Stella Jean travels to Burkina Faso with the Ethical Fashion Initiative to meet with handweaving artisans and source fabrics with local weaving ateliers to create her SS14 collection.

Since this visit, Stella Jean has used hand-woven fabric from Burkina Faso in each of her collections.

Many women used to weave on their own account, however many gave up because it was too difficult to sell their stock and make a living from it. Joining the weaving cooperative allows them to receive many more orders, work with others and improve their skills.

Most importantly, more orders means more income for them to take control of their lives. Clémentine, a mother of three children says that since joining the cooperative she has many more orders and “this means I earn more money which improves my life and the life of my family.” Clémentine was also recently able to purchase a motorcycle which makes her independent and helps her get from work to home.

Most women use the income they receive from the orders placed by fashion houses to give a better life to their children. Mamounata says that with the income earned “I can provide for my family and keep my bike in good condition.” Joséphine is able to feed her family with the money earned and has also managed to resolve some financial issues.

Some women had no background in weaving but decided to give the craft a chance to turn their lives around. For example Véronique used to collect sand and gravel to provide for her family. However, since she joined the cooperative she states that her life has changed because “I can now pay the school fees for my children, medical costs and food. In short, I earn enough to provide for my seven children.” Augustine used to cut wood and also collect sand and gravel to sell. She says that she rushed to join the cooperative as soon as she heard of it and says that “Frankly, my life is now much better. I have six children and I can cover all their needs.”

Learning new skills is very important not only to ensure fabric is woven to high standards but also for the confidence of the women artisans. Brigitte began weaving four years ago and since has learnt many weaving skills during this time. She now feels she truly has a profession because before “I didn’t know how to do anything.” Christine began weaving two years ago and says “My life is much better than before” – she now dreams to own a bike of her own.

The Ethical Fashion Initiative is proud to work with many women weavers from Burkina Faso who have been able to improve and take control of their lives through dignified work, producing fabric for luxury fashion houses.

Photo credits: Anne Mimault & ITC Ethical Fashion Initiative