Tomorrowland: how innovation and sustainability will change the fashion panorama.

On Wednesday, 24th April 2019, Fashion Revolution hosted our fifth annual Fashion Question Time, a powerful platform to debate the future of the fashion industry during Fashion Revolution Week. This year Fashion Question Time was hosted for the first time at the V&A museum and opening the event up to the public for the first time. The theme this year was Tomorrowland: how innovation and sustainability will change the fashion panorama.

Chaired by Baroness Lola Young of Hornsey, this year’s panel brought together leading figures across government and the fashion industry to discuss the future of the fashion industry.

Attendees included high-level fashion industry representatives from across the sector, global brands, retailers, press, MPs, influencers, and NGOs. Panelists included Mary Creagh, MP and Chair of the Environmental Audit Committee; Laura Balmond, Project Manager, Ellen MacArthur Foundation; Mark Sumner, Lecturer in Sustainability, Fashion & Retail, University of Leeds, and Hendrik Alpen, Sustainability Engagement Manager, H&M Group.

After a welcoming speech from Tim Peeve, an opening speech was made by Sarah Ditty, Policy Director for Fashion Revolution:

“There is an ocean of truth lying undiscovered before us when it comes to the fashion industry of tomorrow. We urgently need to focus on innovation and we need sustainability to be scaled up.”

Below we have selected some questions and answers that were discussed over the 1 hour ½ debate during Fashion Question Time 2019 at the V&A:

Olivia Shaw, Campaign Support Officer for #LoveNotLand

fill and London Waste & Recycling Board asked:

“In a world with finite resources, why does the fashion industry waste around three quarters of what it creates and how are we going change this model to create a fair system for all?”

Laura Balmond, Project Manager, Ellen MacArthur Foundation: It’s not possible to continue as we go on… The amount of clothes produced is rapidly increasing – and we are using clothes 40% less. Less than 1% of materials are going back into fashion we make… We need a huge systemic rethink .. I believe that the circular economy will be business-led. We need businesses to get behind this common vision… The current system doesn’t work. The leaders will continue to push ahead – will the others exist in 5 years time?

Mark Sumner, Lecturer in Sustainability, Fashion & Retail, University of Leeds: Technically there are lots of solutions but there’s no motivation… We have the opportunity to change this and legislation plays an important role. The fashion industry has been around for thousands of years. It plays an important role in self-esteem and identity, plays an important part in our lives. But we can’t stick with the model we have at the moment, we need to change. The Modern Slavery Bill is a good starting point but we need more legislation. More innovative structures in place to penalise businesses – the responsibility needs to be across the whole system.

Mary Creagh, MP and Chair of the Environmental Audit Committee: The current fashion industry model promotes over consumption and under utilisation. My concern is that the policy space in this country, which has historically been a leader on these issues, has been crowded out by the Brexit psychodrama and the space for creative and necessary responses to this is being handed to us. We’re in a unique situation where the public is dragging the Government. We debated the environment twice in Parliament twice yesterday so things are changing but we all need to think about our overconsumption… We also need to strengthen regulation to require greater executive level accountability for tackling modern slavery and reducing greenhouse gas emissions in business and supply chains.

Hendrik Alpen, Sustainability Engagement Manager, H&M Group: Moving to a circular model makes business sense. Right now, H&M operates one of the biggest global take-back schemes.

Sarah Ditty, Fashion Revolution, Policy Director on behalf of Labour behind the Label asked:

The one safety initiative that came out of the Rana Plaza collapse, the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, is at risk of being expelled from the country at the moment, putting all the progress made in the last six years at risk. At the moment over 50% of the factories still lack adequate fire alarm and detection systems and 40% are still completing structural renovations, these life-saving remediations need to be overseen by the Accord. With the Accord under threat, how can innovations in transparency create a better future for garment workers?

Laura Balmond, Project Manager, Ellen MacArthur Foundation: With innovations around transparency, relies purely on the information that is inputted at the very beginning. So, this then raises the question of how do we verify that and how do we ensure the information you are receiving is correct? Therefore, what are the financial incentives to improve the system? We must incentivise accurate data inputting.

Hendrik Alpen, Sustainability Engagement Manager, H&M Group: The Accord is a very well working mechanism. So, we as a brand, and other brands hope it will continue. Last year 98% of our suppliers were compliant with the Accord’s requirements, and this year, it will be 100% compliance. You talk about incentives, so that’s a sort of incentive we can create to get something back for the work we are investing, besides, you know, it’s the right thing to do. This can also create a level playing field between brands and this is very crucial to make informed choices.

Mary Creagh, MP and Chair of the Environmental Audit Committee:

The real costs of what goes into those clothes are not truly priced. We will only have change if we price clothing based on the material, the labour, and carbon emissions. Those costs are currently passed onto the countries of production… Currently, it’s down to little NGOs to police big brands. Footlocker doesn’t provide an anti-slavery statement on their website, for example… We must make accountants and CEOs accountable for slavery and emissions. Anyone with a pension fund can buy shares in a business, and as a shareholder, you can go to AGMs and to put pressure on these brands.

Sara Arnold of Extinction Rebellion asked:

To have a chance of avoiding the worst effects of the climate and ecological collapse, we must get to net zero carbon by 2025 and halt the loss of biodiversity. The mobilisation we need is unprecedented and as an industry, we should be declaring climate and ecological emergency and acting as so. If this was treated as the emergency that it is, would there be any place for fast fashion? Would there be a place for fashion at all?

Hendrik Alpen, Sustainability Engagement Manager, H&M Group: Obviously, it is hard to say we shouldn’t exist! But I can relate to the thoughts. So, our job is to reduce the impact of what we do. So that’s why we set the goal to be climate positive by 2040, that may be too late, but we are discussing timelines. We have made changes across our stores, and office to be powered by renewable electricity. So, the challenge we have is how do we bring that into the supply chain? And our first goal is to have a climate neutral supply chain by 2030. That’s a huge challenge, we don’t know how to do that, but that’s the challenge we are taking on and we have to take on. Then the question is how can we continue to operate with such a business model which still brings fashion to the people but how do we do that in a better way? Our business model is based on selling products and it still will be for a while and on the other hand, that means jobs for people, joy for people but we need to find a different way.

Laura Balmond, Project Manager, Ellen MacArthur Foundation:

Think of the global population, what do people want, what do people need. Firstly, we need clothes, but then we have a prospect of fashion. Fashion is creative and meets a variety of needs of the people. So you’ve got on the one hand, Instagram bloggers who wear many different outfits and that’s how they’ve learnt to operate. And that’s okay, we don’t want to stifle creativity or fun. At the opposite end of the spectrum, you’ve got the guy that’s had his pair of Levi’s and loves them and doesn’t want them to ever wear out and he’s set for life. So how can the fashion industry rise to the challenge of meeting both these needs and still continue to exist? This can lead to interesting things coming out of this, for instance, an organisation that curates a digital wardrobe, so why do they necessarily need to own clothes at all…This is the end where rental models, swapping will be the way to keep clothes in use for as long as possible, just not with the same person. Then, on the other hand, we need to create well made, durable and repairable clothing. And that’s the challenge for the fashion industry: how can it rise to better meet the needs of the consumers?

Mark Sumner, Lecturer in Sustainability, Fashion & Retail, University of Leeds:

We’ve got 11 years to solve climate change, and I suspect it’s going to be less than that. So I agree, that it’s not fast enough. But I think you need to understand that its systemic part of culture and the part that the fashion industry plays in it. Fashion plays a really important role in our lives, for self-esteem, identity, it’s about projecting our position in society. It a really important part of our lives… I think it’s really interesting when people talk about fast and slow fashion, I go around fabric mills and garment factories, you can see excellent best practice happening in fast fashion supply chain and at the same time, around the corner you see absolutely diabolical conditions in factories supplying to luxury brands, sometimes run by the mafia. So, to think that luxury, fast fashion and slow fashion are different concepts is false. I think what we need to be looking at is brands and retailers that are doing good things, H&M, for example, are trying lots of different models, they haven’t got the answers yet but at least they are trying. Some brands out there don’t even know they have to ask the question about climate change, it’s not on their agenda at all. Those organisations are the ones we really need to metaphorically give them a kick. Different business models need to be developed but that does require significant change, so it’s also about changing the way we behave.

Mary Creagh, MP and Chair of the Environmental Audit Committee:

Thank you [to Extinction Rebellion] for creating the operating space for MP’s like me, who have always been a bit of a lonely voice, to become normalised.

But also, while there is a climate emergency, there’s also a social emergency on hand. And we need to tackle both of these things together. And switching to a low-carbon economy, we have to make it adjust transitionally, we have to make sure we don’t create winners and losers, so that fashion shouldn’t just become something for rich people to enjoy. So, when we look at how we are going to transition, we have got problems with our transport, in agriculture and the way we fuel our homes. So those are the three policy challenges for government. Had we moved from our over-consuming society very quickly, we aren’t going to get to net zero by 2025. The science will tell us what to do to get to net zero by 2050, and then in five years’ time to 2040 and then we’ll aim to get there for 2035. We have wasted the last 10 years, we’ve had no new policy in this country to change behaviour and we’ve done some policy mistakes along the way. I think fashion needs to set out it’s roadmap to net zero. It needs to say how we get to net zero and the target needs to be legally enforceable and not just voluntary.

Dr Mark Sumner, Lecturer in Sustainability, Fashion & Retail, University of Leeds:

This isn’t just about fashion, it’s a culture of consumption. There are brands doing good stuff who are being lambasted by the press and the ones that aren’t doing anything are slipping into the shadows.

Closing Fashion Question Time 2019, Orsola de Castro, co-founder of Fashion Revolution, made a powerful closing speech:

“There is absolutely no excuse anymore. We all have to do what is required of us as people, people working in companies, in governments, in education, in the media, and at home. We have to fight the system and we have to fight our lifestyle. We can’t do this without information and we can’t access verifiable, comparable and understandable information without transparency and public disclosure… We have to move from a culture of exploitation to one of appreciation and place respect for resources and for each other before every deed and every process.”

The other questions asked were:

Antonio Roade, Senior CSR Manager, New Look asked:

Technology will be vital to transition towards a circular economy; and we keep on seeing big companies investing millions collaborating with different research institutions; in different areas and often with no clear outputs. How do we coordinate different initiatives and who should be taking the lead on this (research institutions, governments or brands)?

Elle L, Artist, Expert Advisor in Fashion and Media to United Nations Environment Programme asked:

As we know, fast fashion uses a lot of synthetics which we in the room and the government now know to be highly toxic and damaging to the environment — do you think that a tax can and should be implemented to minimise or how do we phase out the amount of synthetics produced?

Julie Hill, Chair of WRAP asked:

What are the best tools to drive resource efficiency and transparency in the fashion supply chain?

Jennifer Eweh, Designer and Entrepreneur, Eden Diodati asked:

What are the opportunities and challenges involved with automation, blockchain, and artificial intelligence being used within the fashion supply chain?

Siobhan Wilson, Owner, The Fair Shop asked:

Small business and organisations have been driving change in communities across the country and beyond in making, repairing, reinventing and reusing. How can these businesses be nurtured and supported more here in the UK, so they can flourish at a greater scale and gain further exposure to a mainstream fashion audience?

Jasmine Hemsley, Cook, Author and wellness expert, asked:

What will our future look like without sustainable fashion being commonplace?

A very special thank you to the Edwina Ehrman for opening the V&A to Fashion Revolution’s Fashion Question Time and to the rest of the V&A team for your efforts in making this event a success. And a thank you to Sienna Somers and the rest of the Fashion Revolution team for organising this event.

All images Copyright Rachel Manns / www.rachelmanns.com / @rachel_manns / Rachel Manns is an internationally commissioned freelance photographer based in London, UK. She has spent the last decade shooting for a range of clients all over the world. She has a strong passion for sustainability and human rights. With fierce ethical values and a beautiful visual style, Rachel’s work perfectly intertwines the two. Her aim is to use her camera to aid positive change globally, whether that’s politically or commercially, whilst never compromising on aesthetic. Get in contact for rates.

Photo: Shilpi Rani Das started working in a garment factory when she was 12 years old and moved to work at Rana Plaza at 13. She was working on the 8th floor at the time of the factory collapse. She lost an arm and spent the next 2 1/2 years in hospital. She is now at school, plays badminton and supports her family by sending money home. She is starting Open University.

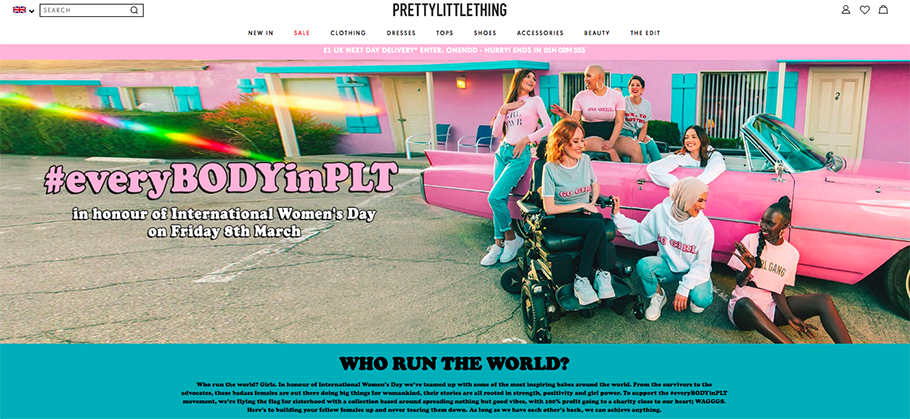

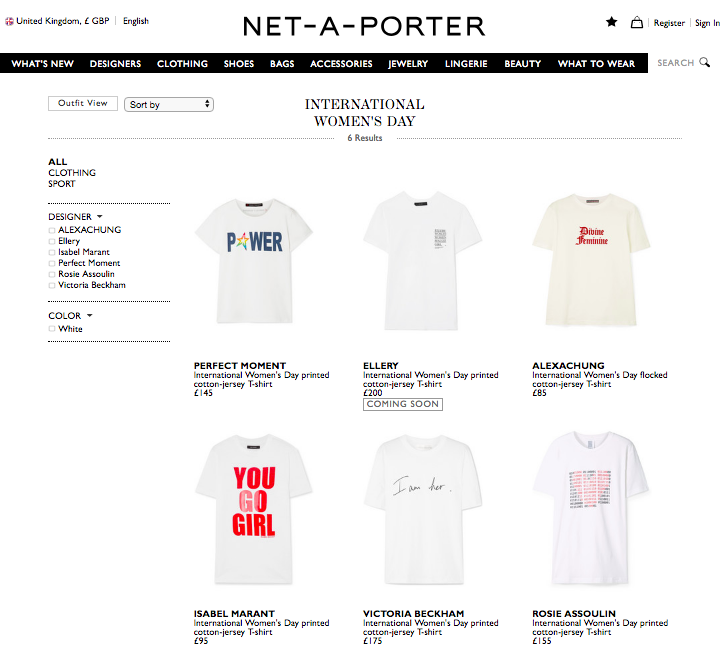

The theme of International Women’s Day 2019 is #BalanceforBetter and asks how we can help forge a more gender-balanced world. Brands and retailers are, predictably, all doing their bit to show support, from Pretty Little Thing’s promotion of their #EveryBodyInPLT movement with T-shirts from £10, with profits going to the charity WAGGGS to Net-a-Porter’s limited edition collection in collaboration with six female designers, with profits going to Women for Women International.

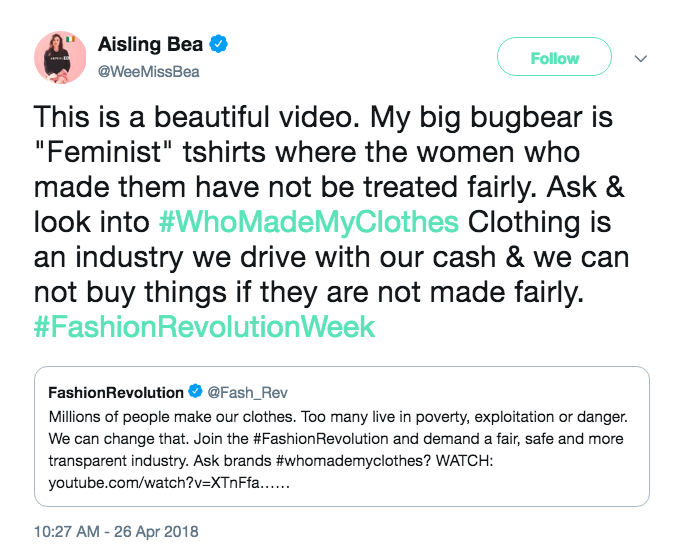

None of the webpages about the T-shirts feature any information about how or where they are made or who made them. About 75 million people work directly in the fashion and textiles industry and about 80% of them are women. Many are subject to exploitation and verbal and physical abuse. They are often working in unsafe conditions, with very little pay.

Actress Aisling Bea tweeted during Fashion Revolution Week last year: “My particular bugbear is feminist tees which were not made by women who were paid fairly for their labour. Check your tags and brands.”

Slogan T-shirts with female empowerment messages will be everywhere this week to coincide with International Women’s Day, but the reality is that the fashion industry doesn’t empower the majority of women who work in it. Gender-based inequality remains a problem throughout the industry, from the highest levels of management to the shop floor and the factory floor. We still have a very long way to go until everyone who makes our clothes can live and work with dignity, in healthy conditions and without fear of losing their life.

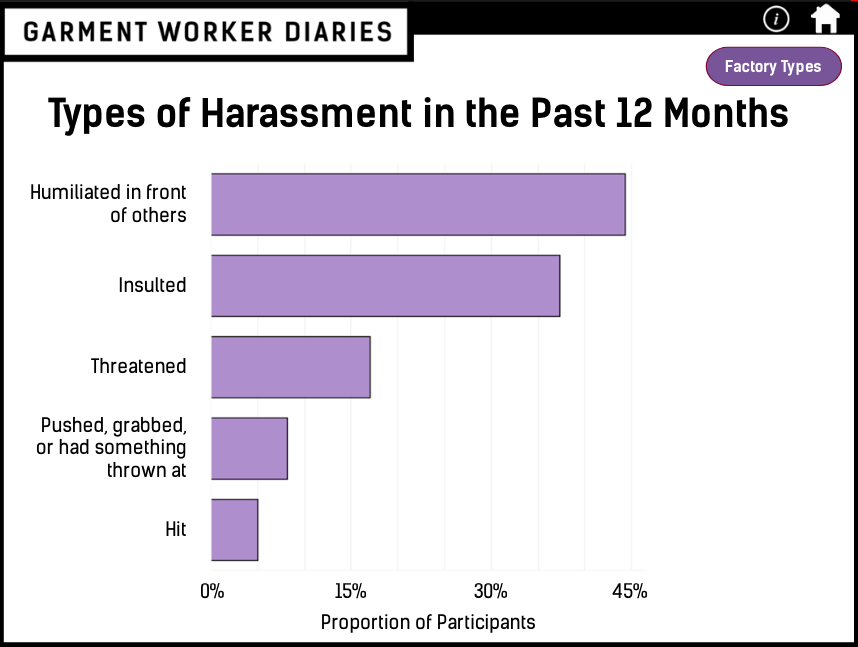

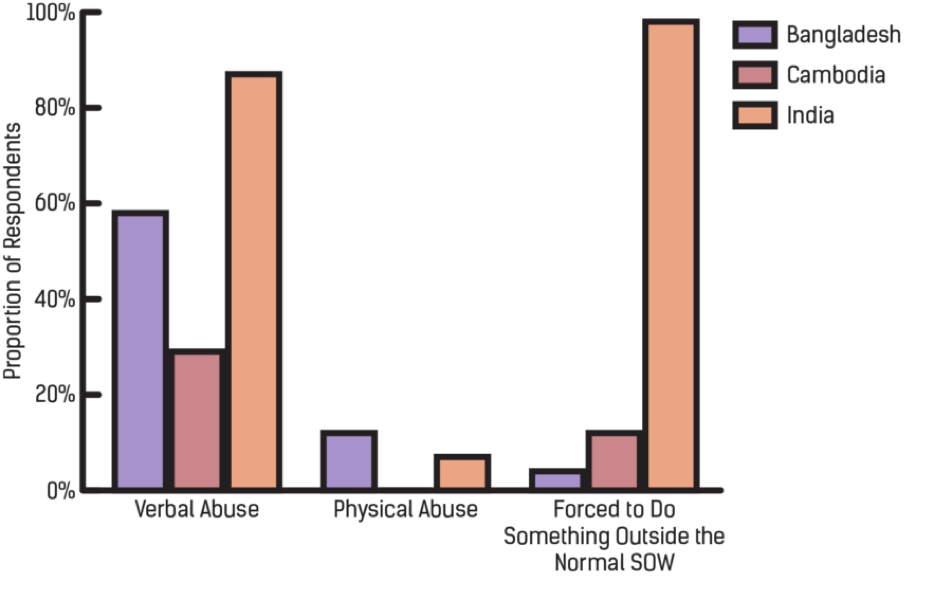

One of the main projects Fashion Revolution worked on in 2017/18 was the Garment Worker Diaries. On-the-ground research partners met with 540 garment workers in India, Cambodia and Bangladesh on a weekly basis for twelve months to learn the intimate details of their lives. 60% reported gender-based discrimination, over 15% reported being threatened and 5% had been hit. When I met with the President of the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association in November 2017, he told me categorically that sexual harassment doesn’t exist in garment factories in Bangladesh. One statistic I found particularly shocking was that 40% of the workers surveyed had seen a fire in their place of work. The women making our clothes are still risking their lives every day for our fashion fix.

In January, The Guardian revealed that Spice Girls T-shirts raising money for Comic Relief’s Gender Justice campaign were being made at a factory in Bangladesh where women earned 35p an hour and claimed to be verbally abused and harassed. Garment production in Bangladesh is still carried out in a very opaque manner and the lack of information about where our clothes and shoes are made and who made them is a huge barrier to changing the fashion industry. This means that gender inequality and human rights abuses and remain rife. If you can’t see it, you can’t fix it, which is why Fashion Revolution urges all brands and retailers to have full supply chain transparency, and we track this through our annual Fashion Transparency Index.

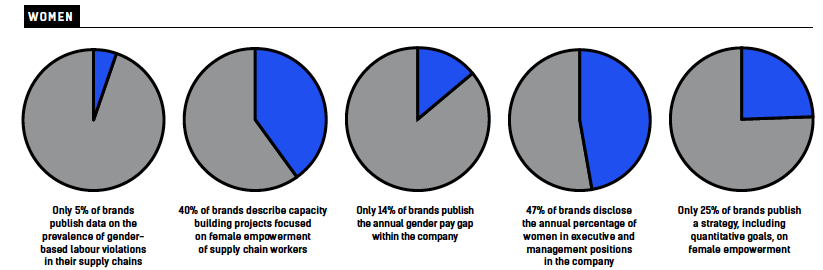

Fashion Revolution’s Fashion Transparency Index 2018 which reviews and ranks 150 major global brands and retailers according to their social and environmental policies, practices and impacts, throws a spotlight on how brands and retailers are tackling gender-based discrimination and violence in supply chains. The report specifically looks at how they are supporting gender equality and promoting female empowerment, both in their own company and in the supply chain.

Whilst, most brands publish policies on discrimination, harassment and abuse, the research show that only 37% of brands are publishing human rights goals. Without reporting on goals and, importantly, annual progress towards these goals, consumers have no way of knowing whether their clothing purchases are really helping to drive improvements for the women who are making their clothes.

Only 40% of brands and retailers reported on capacity building projects in the supply chain that are focused on gender equality or female empowerment, while just 13% publish detailed supplier guidance on issues facing female workers in their Supplier Codes of Conduct. Only 37 out of the 150 brands surveyed report signing up to the Women’s Empowerment Principles, an initiative by the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality, or publishing the company’s overall strategy and quantitative goals to advance women’s empowerment. Meanwhile, just 5% of brands are disclosing any data on the prevalence of gender-based labour violations in supplier facilities, such as sexual harassment and other forms of gender-based violence, or the treatment and firing of pregnant workers.

In the 2019 Fashion Transparency Index, to be published in April, we will be surveying 200 brands and asking the same questions around women’s empowerment. Women’s economic empowerment and closing gender gaps at work is key to realising women’s rights and central to achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, in particular SDG 8 on promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.

According to the BoF McKinsey & Company report The State of Fashion 2019 “Younger generations’ passion for social and environmental causes has reached critical mass, causing brands to become more fundamentally purpose driven to attract both consumers and talent”. As a result, the appearance of the word “feminist” on retailer homepages and newsletters is forecast to increase in frequency sixfold compared to two years ago. Brands are adopting feel-good feminist slogans, yet the rise of real feminism and female empowerment within the industry is a long way off for most women who work in it, from the highest levels of management to the shop floor and the factory floor.

If we really want to see a more gender balanced world, brands and retailers need to do more than sell empowering T-shirts; they need to make sure their policies are put into practice. And not just in the visible places, on fashion shoots or within their company, but at every level of their supply chains. The people making our clothes may not be visible, but every garment they make has a silent #MeToo woven into its seams. At Fashion Revolution, we believe positive change in the fashion industry is possible, and it starts with transparency.

In Autumn 2018 the Environmental Audit Committee wrote to sixteen leading UK fashion retailers, among them M&S, ASOS and Boohoo, asking what they are doing to reduce the environmental and social impact of the clothes and shoes they sell. Today they released their Interim Report on the Sustainability of the Fashion Industry.

Fashion Revolution welcomes the UK Environmental Audit Committee’s findings of their inquiry into the sustainability of the fashion industry. We too want to see a thriving fashion industry in the UK that employs people, inspires creativity and contributes to sustainable livelihoods in the UK and around the world. We agree with the Environmental Audit Committee’s conclusion that the global fashion industry is exploitative and environmentally damaging and that brands and retailers have an obligation to address the fundamental business model.

This report states “We believe that there is scope for retailers to do much more to tackle labour market and environmental sustainability issues. We are disappointed that so few retailers are showing leadership through engagement with industry initiatives.”

Fashion Revolution believes that fashion brands and retailers should sign up to pledges and multi-stakeholder initiatives which are working towards improving workers’ rights, paying a living wage and striving towards a closed loop system. They should also use our Transparency Index as a tool to disclose more about their social and environmental policies, practices and impact both within their companies and throughout their supply chain.

The Committee believes that “The fashion industry’s current business model is clearly unsustainable, especially with a growing middle-class population and rising levels of consumption across the globe. We are disappointed that few high street and online fashion retailers are taking significant steps to improve their environmental sustainability”. Brands are criticised for inadequate sustainability actions and initiatives. The report concludes that recycling waste and complying with the Government’s Carbon Reduction Commitment is not sufficient to offset the environmental damage caused by the fashion industry.

We believe that the fashion industry in the United Kingdom and globally needs far reaching systemic change in order to tackle poverty, inequality and environmental degradation and greater transparency is the first crucial step towards solving its human rights and environmental crises. Our Fashion Transparency Index research has shown that some major brands and retailers are making significant efforts to tackle these issues in their companies and across their supply chains, whilst at the same time far too many large brands and retailers are turning a blind eye. Increased transparency means issues along the supply chain can be identified, addressed and remedied much faster. Greater transparency also means best practice examples, positive stories and effective innovations can be more easily highlighted, shared and potentially scaled or replicated elsewhere.

In an Ipsos MORI survey of 5,000 people across the five largest EU markets published by Fashion Revolution in November, consumers told us they want to know more about the social and environmental impacts of their garments when shopping for clothes and they expect fashion brands and governments to be doing more to address these issues. 77% strongly/somewhat agree that fashion brands should be required by law to respect the human rights of everybody involved in making their products, 75% strongly/somewhat agree that fashion brands should be required by law to protect the environment at every stage of making their products. The majority of people surveyed believed governments should be responsible for holding fashion brands to account for disclosing information about the way their products are made, what suppliers they are working with and how they’re applying socially and environmentally responsible practices in their supply chains.

It is clear that greater government intervention will be necessary if companies are to be held to account for the impacts of their practices on people’s lives and the environment. We want the U.K. Government to pass mandatory due diligence laws, building upon the recent regulatory examples in France and Switzerland. Ultimately, if the UK Government is serious about improving human rights, social impacts and environmental sustainability in the fashion industry, then it must rewrite the rules of the economy so that shareholder profit is no longer prioritised above the protection of our ecosystems and the health and wellbeing of our communities.

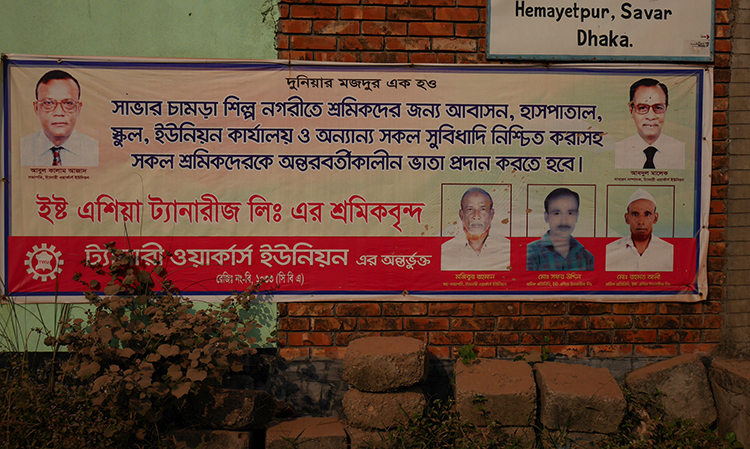

In transit from Bangladesh to Manchester, I walked past the luxury stores in Dubai airport, all of which have leather bags displayed in their windows. The spotlights in the store windows shine down on an array of beautiful bags, but I want to shine a spotlight on a darker story which needs to be revealed. The previous day I had visited the tanneries in Dhaka, Bangladesh, where the leather used for many of the world’s designer bags and shoes originates.

Until recently, the district of Hazaribagh housed the majority of Bangladesh’s tanneries. Not only did severe labour abuse, including child labour, take place but decades of untreated chemical waste has poured into the local Buriganga river, affecting local communities and habitat. In particular, chromium from the tanneries has affected fish populations on which the red-listed endangered Ganges river dolphins prey. Concentrations of chromium are up to 100 times the level prescribed by the World Health Organisation for drinking water.

In an attempt to improve conditions for workers and prevent further environmental pollution in the growing leather sector, the government of Bangladesh decided to relocate the tanneries from Hazaribagh to Savar. The move has been beset by delays: initially scheduled for 2005 completion, an article in Bangladesh’s Daily Star newspaper on 8 November reported that the project has been delayed yet again and they are now aiming for completion in June 2019.

Meanwhile, 92 of the 155 tanneries have already been relocated to Savar, most of which have double the land and therefore at least double the production capacity of their previous facilities. However, the infrastructure and utilities for the tanneries are from adequate, whilst facilities for relocated tannery workers do not even meet their basic necessities of housing, health, education and transportation.

I was visiting unannounced, hoping to talk to workers and managers about the environmental and social problems created by the move. I followed a truck piled high with hides into the Savar Tannery Estate. The smell was a good indication we were approaching the tanneries – a powerful odour which intensified on approach.

The roads were not only potholed, but were covered in surface effluent. The Central Effluent Treatment Plant for the new Savar Tannery Estate is not yet fully functional, drainage systems are not in place and tannery effluent is flowing into local drainage ditches and into the Dhaleswari river. According to the Rapid Assessment of Hazaribagh Tanneries report recently published by SANEM, analysis of data and samples collected at discharge points from the treatment plant, as well as from the Dhaleshwari river, have produced alarming results. Everywhere I looked, drainage ditches were visibly flowing with chemical effluent, with one drain running behind a row of food stalls serving meals to the tannery workers. The government shifted the tanneries due to pollution of the river but ultimately the same thing is happening in Savar.

As I walked from the car towards the first factory I spotted something else on the road – animal tails lying discarded on the ground. Solid waste is being dumped in the streets because a protected dumping yard has not yet been set up.

Environmental issues are not the only problems caused by relocating the tanneries before the infrastructure is complete. A sign outside a factory, put up by the Tannery Workers Union, says: “We demand hospital, residence, school, development centre and other benefits should be assured and all past dues should be settled for the workers.”

In the first factory I visited, the foreman was candid about what the urgent improvements needed within the locality. “If there is a serious injury we can’t get the worker to hospital on time. There are no primary healthcare services here. A lot of our workers need ongoing medical support due to skin rashes but we don’t have such facilities here. There is almost no accommodation in the area. There is some but it is expensive so the workers have to commute for 120 taka each way every day (£1.10) and it takes 1.5 to 2 hours. 95% of our country is Muslim yet we don’t have a mosque here.”

I also observed many young workers in the factories, all working without any protective equipment. The sector has an 11% child labour rate, but there is also a problem with young labourers on apprenticeships who should be aged 16 to 17, but often start at 15. Apprentices are allowed to work 30 hours over a six-day week, plus 6 hours maximum overtime across the week, but they are working far more in the tanneries.

Returning to Dhaka, I visited the offices of Awaj Foundation where I talked to Nahidoc Hasan Nayan, Director of Operations, about the tanneries and what steps needed to be taken in order to resolve the myriad problems I had seen that morning. Accommodation costs in Savar are very high compared to Hazaribagh and housing is insufficient, but if workers don’t move the high cost of the commute means their real wages have decreased and they are working below the poverty line. The workers also need schools for their children and medical facilities, which are currently 10-15km from the tanneries. If a factory has 150 workers they should by law have first aid inside the factory but this is not happening. It could easily take over an hour to get to medical facilities due to the traffic jams. Workers are not using personal protective equipment so the risks are high. There is one union for tannery workers, but according to Mr Nayan it is working for the factory owners not the workers.

“Workers are worse off,” stated Mr Nayan,“I found 12 year old boys there last week who have no idea they are working in such a dangerous place.

Part of the problem is that brands don’t come to the tanneries; buyers only engage with the factories,” he continued.

Although the foremen in the tanneries did not know for which brands the leather was destined, I was told in one of the tanneries that the leather would be sent to China and Italy. In Fashion Revolution’s 2017 Fashion Transparency Index which reviews and ranks 100 of the biggest global fashion and apparel brands and retailers according to how much information they disclose about their suppliers, supply chain policies and practices, and social and environmental impact, we found that only 14% of brands were publishing their second tier factories, which sometimes includes tanneries. No one is publishing a list of raw material suppliers, so there is no way for consumers to know where the leather comes from or what animal welfare standards are in place.

The leather and footwear industry is the second largest revenue generator in Bangladesh. Although far behind the Ready-Made-Garment sector at $2 billion USD compared to $28 billion USD, footwear production is expected to become the next area of growth in Bangladesh, putting more pressure on the tanneries as they meet increased demand. The footwear industry comprises 35-50% women but they are not getting maternity leave, nor are workers receiving medical leave or holidays, only festival leave. Not all are getting minimum wage in both the tanneries and the footwear factories, particularly in smaller factories. According to Mr Nayan, only 5-10% of the factories have adequate working conditions.

The move to Savar was planned as a means of improving social and environmental standards but quite the opposite has occurred. So what needs to happen now? Workers urgently need compensation for the wages they lost during the 3 to 4 month transition period from Hazaribagh to Savar when they were unable to work. Transportation must also be organised for workers until affordable, local accommodation is in place. The Central Effluent Treatment Plant urgently needs completion as the current situation is just moving environmental pollution from one site to another. Ultimately, all stakeholders need to take measures to improve working conditions, benefits and health and safety standards so this move has a positive long-term effect on the environment, workers and their families.

As consumers, we can also play a part by asking the question #whomademyclothes, telling brands we need more transparency in fashion supply chains right back to the tanneries and the raw materials.

Many of the social and environmental problems we are seeing in the tanneries are the same ones that beset the garment factories from their inception in the early 1980s until post- Rana Plaza scrutiny started to bring about change. As the leather sector expands in Bangladesh, let’s not make the same tragic mistakes we made with the garment industry.

Carry Somers visited Bangladesh as a guest of the Bangladesh Denim Expo which this year had a focus on Transparency.

For further information on the Rapid Assessment of Hazaribagh Tanneries report, see SANEM

Textile Exchange has set up the Responsible Leather initiative to create responsibility in the leather supply chain.

What the lives of garment workers can teach multi-national brands and their customers

Fatima, Sokhaeng, and Usha are all garment workers making clothes for multi-national brands in factories across South and Southeast Asia. Fatima lives and works in Dhaka, Sokhaeng in Phnom Penh, and Usha in Bangalore. Their work is similar—cutting and sewing garments for eight or more hours per day, but their lives and the lives of their compatriots also vary in important ways. What can the lives of these women teach multi-national brands and their customers about how to create and maintain sustainable supply-chains, where people who make the clothes that the world wears are treated with respect and do more than just survive? In other words, how can brands, with the support of consumers, win the “race to the top” where all do well, rather than the proverbial “race to the bottom” where brands compete by getting as much out of their workers for as little as possible?

Fatima, Sokhaeng, and Usha are three of 540 women that Microfinance Opportunities has been tracking for the last eight months or so. We have been asking them about how they earn and spend their money, their daily schedules, whether they are happy, in pain, or suffered an injury, the conditions in their workplace, and any special events that happened in their lives. From this information we have been able to weave together the individual stories of the workers, as well as generate an aggregate picture of the lives of the women who make our clothes. You can find accounts of these stories here for Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India.

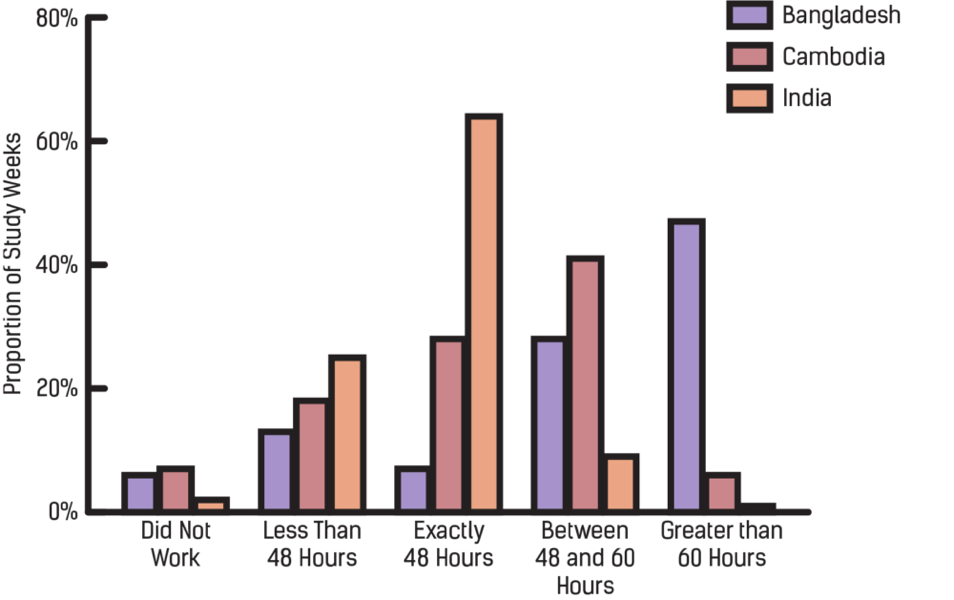

Fatima and others like her who are participating in the Garment Worker Diaries in Bangladesh often worked over 60 hours a week in the latter part of 2016 during the first few months of the study. In contrast, Usha and the other workers in Bangalore invariably worked 48 hours a week or less—still a lot but far less than the women in Bangladesh. The women in Cambodia fell somewhere in between—48- to 60-hour weeks were the most common in Cambodia. Furthermore, in both Bangladesh and Cambodia, the number of hours the women worked per week varied far more than they did in India, where the women consistently reported 48-hour weeks.

Figure 1: Hours Worked per Week

From the reports of how many hours they worked and how they varied from week to week, it looks like the women in India are the best off. But this is not altogether the case. Usha and her Indian counterparts reported far higher levels of verbal abuse in the workplace than did the women in Dhaka or Phnom Penh. And women in India consistently reported being forced to do more work than their allotted quota for the day. Meanwhile, women in Cambodia had the fewest reports of verbal abuse and no reports of physical abuse.

Figure 2: Reports of Abuse at Work

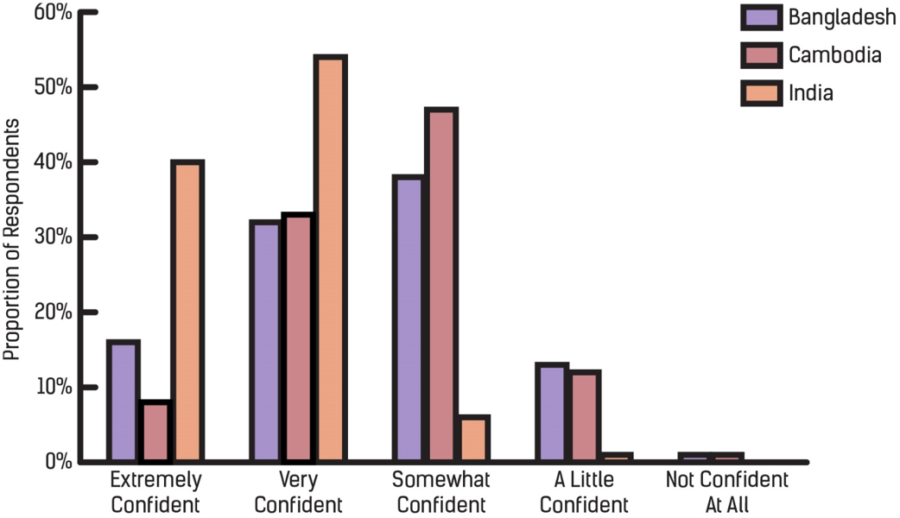

Further complicating the picture, women in Bangladesh and Cambodia participating in the Diaries study reported having mixed levels of confidence in whether they would be able to use the emergency exits in their workplaces in case of an emergency—almost 40 percent of Bangladeshi and 50 percent of Cambodian workers were only somewhat confident, while the Indian women reported the most confidence—over 90 percent reported they were extremely or very confident.

Figure 3: Confidence in Use of Emergency Exits

There may, of course, be differences across the countries in how the women perceive their situation, but even taking this possibility into account the differences across countries are so great that it is hard to fathom that they are simply due to differences in perception. What these findings suggest is that just because a set of factories in one country have worse conditions than factories in another country on one dimension does not mean that they have the worse conditions on all dimensions. So why can’t factories in Bangladesh and Cambodia and the brands that hire them have their workers work reasonable hours? Why can’t Indian factories stop the verbal abuse their workers suffer? Why can’t the Bangladeshi and Cambodian factories ensure that their workers can use designated exits in an emergency?

From a human rights perspective we can simply argue that the factories and the brands that hire them should stop treating their workers badly and adhere to some basic standards—higher than the best experiences of the women in our study. But these findings suggest that even by the lower standards of “business necessity” there is no justification for the behavior of the factory managers and the brands that hire them: other factories are able to treat their workers better in certain ways and stay in business, so why shouldn’t all factories be able to do so? In other words, there is no excuse for the treatment of the workers that the Diaries data are revealing, even by the lower standard of “we have to treat our workers this way just to stay in business.” It is time that the brands send this message loud and clear to factory managers, and that consumers ask the same of the brands. This way, maybe we can see the beginnings of a “race to the top.”

Strikes, Rents, and Wages

During the last two weeks of 2016, as consumers in the United States and Europe were donning their new holiday outfits, the garment workers who made those clothes in the manufacturing hub of Ashulia in Bangladesh were being arrested by police, and factory owners sacked workers by the thousands.

The heavy-handed actions were a response to workers’ protests against high rents and low wages. Garments workers said they could not pay rent and purchase daily necessities like food, basic clothing, and medicine on the paltry minimum wage of $68 a month. In response, the Government of Bangladesh’s Minister of Commerce Tofael Ahmed announced that the government would ensure that rents in the Ashulia area would not increase for three years.

Unfortunately, new data from Microfinance Opportunities’ Garment Worker Diaries shows that current rent levels are driving garment workers to accumulate debt in order to provide basic necessities for themselves and their families. Consequently, the government’s promise to hold rents steady is unlikely to provide workers with financial relief.

Debt for the Renters

We are currently conducting weekly interviews with 181 female garment workers who live in manufacturing hubs throughout Bangladesh, including 16 who live in Ashulia. Two-thirds of the sample are responsible for paying their household’s rent. Women who do and do not pay rent share many similarities. The majority of the women are married, and they have comparable education levels and positions in their factories, although those who pay rent are slightly older. The women that are married live with their husbands and children in one room with no bathroom or formal cooking area; those that are not share similar spaces with other family members or other garment workers.

The economic behavior of these two groups is as different as their demographic characteristics are the same. The data make clear that rent is a huge burden for the two-thirds of women who pay it, demanding 40 percent of the value of a monthly paycheck on average. These women purchase goods on store credit more than twice as often as the women who do not pay rent, borrowing goods each month with a value equivalent to almost 20 percent of an average paycheck. The goods they purchase are not luxuries – they borrow basics like food, soap, and medicine for themselves and their families.

Women who pay rent use more cash loans too – they receive cash loans once every two months on average compared to once every four months for those who do not pay rent. Women who pay rent borrow loans that are almost three times the size of the ones that other garment workers borrow. At $37, these loans are roughly equivalent to our garment workers’ monthly rent.

Debt, In Cycles

Women do not acquire this debt haphazardly or in response to unusual events – their behavior is cyclical. In the weeks between monthly paychecks, women borrow goods from store vendors and take cash loans, using the cash to purchase basic goods they cannot get on credit and to pay rent for the upcoming month.

Their paychecks make them flush with cash but only for a moment – in addition to rent, they have to repay their outstanding loans from the previous month. After paying their rent and these loans, they are short on cash, and the cycle of taking on and repaying debt begins again.

Holding Rents: Nothing More Than a Platitude

This cycle has the makings of a catastrophe. An unexpected event, like a medical emergency, could be devastating for women already living on the financial edge. Women who lose their factory jobs may be unable to repay their debts, forcing them to borrow from riskier sources, and pushing them deeper into a debt trap.

From this perspective, the Government of Bangladesh’s promise to hold rents steady is nothing more than a platitude, a promise that while garment workers’ rent-induced stress may not increase, it will not be relieved in the near future. Instead, the workers will continue to exist in a status quo defined by the pressure of borrowing to make ends’ meet and working 60 hour weeks to ensure debts can be paid.

by Eric Noggle

The Garment Worker Diaries is a yearlong research project that is collecting data on the lives of garment workers in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India. Microfinance Opportunities is leading the project with support from C&A Foundation. Fashion Revolution will use the findings from this project to advocate for changes in consumer and corporate behavior and policy changes that improve the living and working conditions of garment workers everywhere.

Follow the yearlong study on social media #workerdiaries

Authors: Conor Gallagher and Guy Stuart, Microfinance Opportunities

Four years ago today, a fire at the Tazreen Fashions factory outside Dhaka killed 112 garment workers and injured nearly twice as many. In its aftermath, there was an international outcry calling for greater regulation of health and safety conditions in garment factories across the country. Clothing brands and retailers came together and agreed to better monitor conditions inside the garment factories where their clothes are made; and then, after the Rana Plaza disaster, the Bangladeshi government adopted new legislation to strengthen its regulatory body in conducting safety inspections. As of March 2016, the Department of Inspection for Factories and Establishments had inspected 1,549 ready-made garment factories across the country.[1] Despite these steps, workers in garment factories continue to face poor health and safety conditions not only in Bangladesh but in other major garment exporting countries as well. These poor conditions do not necessarily result in major tragedies such as those at the Tazreen Fashions factory or Rana Plaza, but they nevertheless expose the workers in the factories to unsafe conditions and cause them undue pain and suffering.

Through the Garment Worker Diaries project, research teams in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India have been collecting weekly data on what garment workers earn and buy each week, how they spend their time each day, and whether they experience any harassment, injuries, or other significant events while at the factories. Though we are still in the early stages of data collection, our project covers 540 workers from across these three countries, and we are hearing from them about the health and safety hazards they face.

Workers in our study have informed us about major events that have taken place in the factories. In Bangladesh, women from two different factories have reported fires. In the first case, a fire broke out during their lunch-break, and workers had to put it out themselves. In the second instance, a fire broke out during a midnight shift and took an hour to be extinguished. No casualties were reported in either case.

In Cambodia, one worker informed us that her factory’s owner had not paid their salary, so she ended up going to stand guard at the factory to try and force him to pay. She then filed a complaint in court against the owner in the following week, again asking him to pay. This was more than two months ago, and the situation has still not been resolved. We have seen similar incidents in Bangladesh. For example, six workers from a factory near Dhaka reported a factory-wide strike as the owner had not paid their salaries on time. This resulted in altercations with police officers, pressuring the owner to pay shortly after the fights broke out.

Not all issues that workers face are major events like fires or strikes; workers have been telling us about some more frequent and persistent challenges they deal with too. Workers in our study have reported on repeated harassment in the work place. These incidents range from being yelled at or insulted to sexual harassment. In Cambodia, workers have been willing to share with us the insults they receive. Some examples include women being called “idiots” or “crazy girls,” while one woman’s supervisor told her that she had “no bright future with [her] careless working style.”

Finally, the workers in our study tell us about the pain they endure because of their work. In India and Cambodia, for example, we have found that workers regularly report instances of chronic pain. Respondents in these countries have common ailments: for India, workers commonly experienced back pain. In Cambodia, workers most commonly have reported suffering from headaches. These types of pain are common among garment factory workers who face uncomfortable working conditions that require them to stand in hunched positions performing repetitive tasks for hours on end. Eventually, these conditions wreak havoc on the workers’ bodies, causing the types of chronic pain that our respondents regularly report. In three extreme cases, workers from India reported experiencing back pain every week, and they have reported that this pain can last anywhere from one hour to several days.

We are still in the early stages of collecting and analyzing the data from the 540 women participating in our study. As the Garment Worker Diaries progresses, we will continue to collect information on what is going on inside garment factories in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India. We will use interviews and surveys to delve deeper into the specific working conditions that workers face.

We now ask you: what would you like to know about the women who make our clothes and the conditions they face at work?

Tell us by tagging us at @fash_rev #workerdiaries

The Garment Worker Diaries is a yearlong research project led by Microfinance Opportunities in collaboration with Fashion Revolution and with support from C&A Foundation. We are collecting data on the lives of garment workers in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India. Fashion Revolution will use the findings from this project to advocate for changes in consumer and corporate behavior and for policy changes that improve the living and working conditions of garment workers everywhere.

[1] http://database.dife.gov.bd/

Header photo credit: IndustriALL Global Union

Fashion Revolution’s theme for 2017 is Money Fashion Power which will be exploring the flows of money and structures of power across the fashion supply chain.

“There is nothing more important than performance, and fashion brands have to perform because of this greed – not a percent or two per year, but at least 10 percent quarterly, even when we’re talking about billion-dollar businesses. There is no end to the greed, so the brands are spreading themselves thin”

said trend forecaster Li Edelkoort in an interview with Deutsche Welle published this week.

Tomorrow is the fourth anniversary of the Tazreen Fashions fire in Dhaka Bangladesh. All of the garment workers were on an overtime shift to complete an urgent order when the fire alarm sounded, but managers ordered them to carry on working. As the smoke and fire spread through the building and workers eventually tried to escape, they found that iron grilles barred the windows and the collapsible gate was locked. None of the fire extinguishers appeared to have been used which suggests workers had not received fire safety training. 112 workers died and more than 200 were injured. The official who led the inquiry into the fire said

“Unpardonable negligence of the owner is responsible for the death of workers.”

After the Tazreen fire, factories were told to replace collapsible gates and lockable doors with fire-proof doors so there was always a safe exit point in the event of a fire. In the Bangladesh Accord’s initial inspection of 1600 garment factories, it was found that over 90% had lockable, collapsible gates. According to industry insiders, around 40% of all operational garment factories still have these gates, four years later.

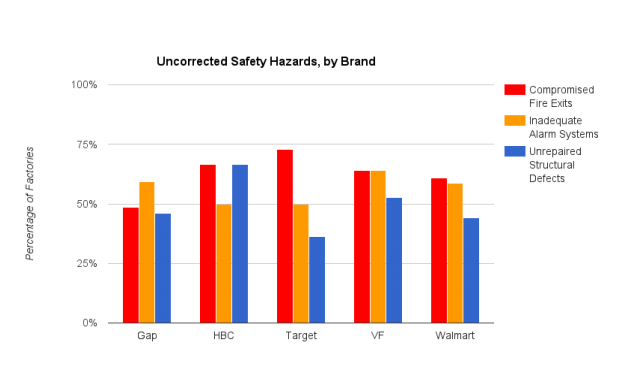

A new report published this week Dangerous Delays on Worker Safety found that of the 107 factories labelled “on track” by The Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, 99 were still falling behind in one or more safety categories. In light of Li Edelkoort’s observation that brands are spreading themselves thin, it comes as little surprise to find that brands in the Alliance, which includes brands such as Walmart, Target, Gap inc, VF Corporation (which owns Lee, Wrangler, The North Face, Vans, Timberland and others and has just published its factory lists) have yet to put in place the life-saving safety changes they pledged following the Rana Plaza disaster, which occurred five months after the Tazreen fire. 62% of factories still lack viable fire exits, 62% do not have a properly functioning fire alarm system and 47% have major, uncorrected structural problems. Deadlines for these safety measures to be implemented were supposed to be 2014/15 but have now been moved to 2018, the end of the 5 year period over which the Alliance extends.

Are brands and factory owners really so concerned with the bottom line that they cannot afford to prioritise the installation of something so basic to worker safety as a fire-proof door and the removal of locks from existing doors?

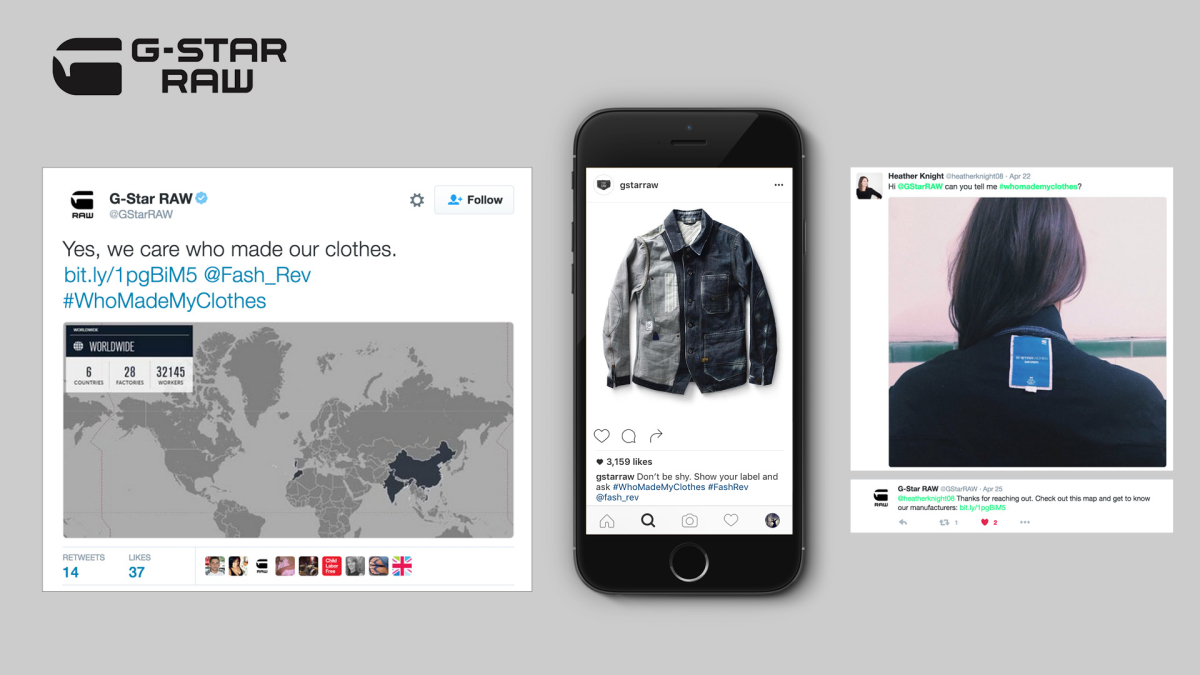

Since the Tazreen fire and Rana Plaza disaster, human rights issues are certainly more visible than ever before and there is ongoing pressure on global fashion brands to become more transparent. Companies are now being held to a higher standard and they are cognisant of this change. During Fashion Revolution Week in April, over 70,000 fashion lovers around the world asked brands #whomademyclothes on social media, with 156 million impressions of the hashtag. G Star Raw, American Apparel, Fat Face, Boden, Massimo Dutti, Zara, Jeanswest and Warehouse were among more than 1250 fashion brands and retailers that responded with photographs of their workers saying #Imadeyourclothes. Read more about our impact here.

However, the harsh reality is that basic healthy and safety measures still do not exist for millions of people who make our clothes and accessories. On 11 November 2016, 13 people died in a factory making leather jackets on the outskirts of Delhi. The front of the building had been shuttered with a metal grill which prevented the workers escaping the blaze. Deadly accidents are still commonplace in fashion supply chains and not enough has been done by brands and retailers to prevent more fashion victims; victims of neglect, oversight and the pursuit of profit.

Scott Nova, executive director of the Worker Rights Consortium says:

“What motivated Walmart and Target to do the right thing is public embarrassment. We are three and a half years on [from Rana Plaza] and they assume memories are fading.”

We have the power and, I believe a duty, to let these brands know that our memories of the Rana Plaza disaster, the Tazreen Fashions fire, and the many other tragedies which have ocurred in the name of fashion, are not fading. By asking the question #whomademyclothes we are applying pressure in the form of a perfectly reasonable question that fashion brands should be able to answer. We are asking them to publicly acknowledge the people who make our clothes; millions of people working in factories, fields, homes and other hidden places around the world. Tragedies like the Tazreen Fashions fire are preventable, but they will continue to happen until every stakeholder in the fashion supply chain is responsible and accountable for their actions and impacts.

As Li Edelkoort said, fashion brands are spreading themselves thin. As their customers, we can help make sure they start to get their priorities right and redress the imbalances of power in the fashion supply chain.

Header photo credit: A young garment worker by Claudio Montesano Casillas

Four million garment workers, mostly women, toil in 5,000 factories across Bangladesh, making the country’s $25 billion garment industry the world’s second largest, after China.

Garment workers generally are paid low wages with few or no benefits and often struggle to support their families. Many risk their lives to make a living.

On November 24, 2012, a massive fire tore through the Tazreen Fashions Ltd. factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh, killing more than 110 garment workers and gravely injuring thousands more.

In the wake of this disaster, garment workers throughout Bangladesh are standing up for their rights to safe workplaces and living wages. With the Solidarity Center, which partners with unions and other organizations to educate workers about their rights on the job, garment workers are empowered with the tools they need to improve their workplaces together.

Learn more about the Solidarity Center’s work in the global garment industry

DISASTER STRIKES TAZREEN

On November 24, 2012, women and men working overtime on the Tazreen production lines were trapped when fire broke out in the first-floor warehouse. Workers scrambled toward the roof, jumped from upper floors or were trampled by their panic-stricken co-workers. Some could not run fast enough and were lost to the flames and smoke.

Hundreds of those injured at Tazreen, like Tahera (above), will never be able to work again. Survivors say they endure daily physical and emotional pain, and often are unable to support their families because they cannot work and have received little or no compensation.

Some 80 percent of export-oriented ready made garment (RMG) factories in Bangladesh need improvement in fire and electrical safety standards, despite a government finding most were safe, according to a recent International Labor Organization (ILO) report.

TAZREEN NOT UNIQUE

The Tazreen fire was not an isolated incident.

Months after the Tazreen disaster, more than 1,000 garment workers were killed when the Rana Plaza building collapsed. Workers were forced to return to the building despite the warnings of structural engineers that the building was unsound.

In the four years since Tazreen, fires, building collapses and other tragedies have killed or injured thousands of garment workers in Bangladesh, according to data collected by the Solidarity Center.

FACTORIES CAN BE MADE SAFE

The Tazreen fire and Rana Plaza collapse were preventable. Workers at Tazreen and Rana Plaza did not have a union or other organization to represent them and help them fight for a safe workplace.

Without a union, garment workers often are harassed or fired when they ask their employer to fix workplace safety and health conditions. They are not trained in basic fire safety measures and often their factories, like Tazreen, have locked emergency doors and stairwells packed with flammable material.

Unions have helped to improve these conditions.

They have joined together to form workplace unions and bargain for safe working conditions, better wages and respect on the job.

UNIONS SAVING LIVES

Worker voices have yielded real results.

Over the past few years, the Solidarity Center has held fire safety trainings for hundreds of garment factory workers. Workers learn fire prevention measures, find out about safety equipment their factories should make available and get hands-on experience in extinguishing fires.

When women workers form unions, they improve their working conditions. Through Solidarity Center workshops and leadership training, more women are running for union office. Women now make up more than 61 percent of union leadership in newly formed factory level-unions.

CHANGE IS POSSIBLE

Salma (below), a garment worker, and her co-workers faced stiff employer resistance when they sought to form a union. With assistance from the Solidarity Center and the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation (BGIWF), to which their factory union is affiliated, workers negotiated a wage increase, maternity benefits and safe drinking water. The factory now is clean, has adequate fire extinguishers on every floor, and a fire door has replaced a collapsible gate.

To learn more about garment workers in global supply chains and how the Solidarity Center supports them, visit www.solidaritycenter.org.

24 April is the most important day for fashion. But not because it’s Fashion Revolution Day. It’s because over 1000 men and women, with families, hopes and dreams just like us, lost their lives while making our clothes.

Did you know that 80% of our fashion is made by 18-24 year old young women around the world? Sadly the only time we hear about these millennial makers is when tragedies such as Rana Plaza occur.

When we ask more about them, we can change their lives. Let’s never forget Rana Plaza and keep asking our favourite brands #whomademyclothes?

By Balmi Chisim, Solidarity Center

More than 1,100 garment workers died on 24 April 2013 when the Rana Plaza building collapsed in Bangladesh, a preventable disaster that injured thousands more workers in the world’s worst industrial accident in years.

Yet their lives likely would have been spared ‘if any of the factories (in the building) had a union’ says union leader Salma Akter Meem. Salma made her observation as she took part this month in a 10-week-long Solidarity Center fire safety training program, one of nearly a dozen such programs the Solidarity Center has held in the past two years.

Salma, 26, started working at age 14 in the garment industry. She says the Rana Plaza building collapse made her co-workers aware of safety issues, and they formed a union September 2013 so they could have a collective voice to create positive changes in their workplace, including making their factory safe.

Blocked from Factory for Trying to Form a Union

Forming a union was not easy, she says. The employer refused to recognize their union even after it received official government registration, which is required in Bangladesh. Employers retaliated against union members, especially against workers on the factory union’s executive committee, Salma says.

‘I was harassed and my union members were banned from entering the factory while we raised our voices and brought attention to the Accord that there was excessive machinery load on the floor and safety issues’ says Salma, who now is general secretary of the factory union.

The Bangladesh Fire and Building Safety Accord, a legally binding agreement in which nearly 200 corporate clothing brands paid for garment factory inspections, was set up after international outrage over the Rana Plaza and the Tazreen Fashions Ltd. tragedy five months earlier, in which more than 100 garment workers were killed when the factory burned down. Since the Tazreen fire, 34 garment workers have been killed in fire incidents and 1,023 workers injured, according to data compiled by the Solidarity Center staff in Bangladesh, according to data compiled by the Solidarity Center in Dhaka, the capital.

Following inspections mandated by the Accord, dozens of garment factories were closed for safety violations and pressing safety issues were addressed.

Standing Strong Together and Winning

Even though some workers were not allowed to work after they formed a union, Salma and her co-workers did not give up in the face of such employer resistance. With assistance of the Solidarity Center and the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation (BGIWF), to which their factory union is affiliated, workers got their jobs back with full compensation for the time they were prevented from working.

Negotiations and discussions with management, finalized in February 2015, have resulted in positive changes, Salma says, with workers getting a wage increase, maternity benefits and safe drinking water. The factory now is clean, has adequate fire extinguishers on every floor, and a fire door has replaced a collapsible gate.

“Changes are possible if you have union and you can make it work.”

Back at the Fire and Building Safety class, Salma says she is ‘learning here not only for me, but also for my factory and family’. She says if workers are safe in a factory and not afraid to raise their voices for a safe and healthy work environment and living wages to support themselves, their workplace contributions will increase, benefiting the employer—and the country.

Header photo: Bangladesh garment workers take part in Solidarity Center fire safety training. Credit: Jennifer Kuhlman/Solidarity Center

H&M ha declarado la “Semana Mundial del Reciclaje” del 18 al 24 de abril de 2016 con una campaña de marketing de gran envergadura que pretende recoger 1.000 toneladas de ropa usada durante esa semana y reciclarlas para convertirlas en nuevas fibras. Fashion Revolution desafió este objetivo, señalando que sólo una pequeña fracción de las 1.000 toneladas propuestas como objetivo pueden convertirse en nuevas fibras textiles ya que la tegnología para ello aún no existe. La organización también desafió lo desconsiderado del momento para la promoción, que coincide con el 24 de abril, justo cuando hace tres años 1.134 personas murieron en Rana Plaza, en Bangladesh, haciendo ropa para cadenas minoristas, y H&M es el mayor productor de prendas en Bangladesh.

Orsola de Castro, co-fundadora de Fashion Revolution ha dicho: “Esta semana, de todas las semanas, H&M debería trabajar en solidaridad con el resto de nosotros para marcar el aniversario de la tragedia de Rana Plaza. Debería ser un momento para todos nosotros para honrar a los trabajadores textiles, aquellos que han muerto en tragedias industriales de la industria textil y aquellos que todavía hoy sufren en la cadena de suministro textil. ”

Fashion Revolution también señalaba el lenguaje confuso usado para describir el impacto de la iniciativa de reciclaje de H&M. Estábamos emocionados de que tanta gente mostrara su apoyo por una mayor transparencia y ayudara a comenzar una conversación sobre temas controvertidos relacionados con la exportación de ropa de segunda mano a países en desarrollo.

“Estamos contentos de que H&M haya admitido las verdaderas cifras de lo que se revende, lo que se reusa y lo que se convierte en nuevas fibras y de que cambiara el objetivo en su web en consecuencia. Esto ha sido algo muy influyente de hecho – usamos nuestra voz colectiva de manera moderada y hicimos que una de las mayores corporaciones del mundo diera un paso hacia una mayor transparencia.

Esperamos que H&M elimine su cupón de descuento en el futuro para no alentar un mayor consumismo entre sus jóvenes consumidores – eso sería el próximo paso lógico al abordar correctamente el tema de los residuos textiles. ”

H&M respondió con el siguiente comunicado: “Tan pronto como Fashion Revolution nos hizo conscientes de sus preocupaciones, comunicamos claramente qe no tenemos la intención de convertir en esta semana en particular como una Semana Mundial del Reciclaje de manera recurrente en el futuro, y hemos ofrecido inmediatamente elegir otra semana si hiciéramos otra Semana Mundial del Reciclaje en el próximo año o siguientes. ”

Fashion Revolution Week tiene lugar del 18 al 24 de abril en 89 países en todo el mundo. Por favor únete y ayuda a aclamar a los verdaderos héroes. Visita www.fashionrevolution.org para encontrar un evento cerca de ti. Juntos podemos hacer que el cambio ocurra.

Por favor ¡apoya a Fashion Revolution para ayudarnos a hacer nuestro mensaje más fuerte! Cada donación nos ayudará a dar voz a todos los implicados en la cadena de producción. Gracias por ser parte de este movimiento y por ayudarnos a seguir siendo fuertes.

Nota para prensa

- Millones de personas saldrán a la calle durante la Fashion Revolution Week para despertar conciencias y hacer preguntas sobre las condiciones a las que se enfrentan los trabajadores textiles y la persistente falta de derechos humanos en la industria de la moda, y para homenajear a la gente que está detrás de lo que llevamos – desde el granjero a la hilandera, la tintorera, sastres y más.

- Durante la semana del 18 al 24 de abril de 2016, te animamos a que pienses lo que hay en tu armario. Si tienes prendas sin estrenar, ¿podrías hacer algo con ellas en vez de deshacerte de ellas (en H&M o en cualquier otro lugar)? Lo podrías intercambiar con un amigo que lo aprecie más, o tal vez lo podrías modificar para que lo puedas seguir amando más tiempo. O por qué no probar nuestra Haulternative, y descubrir 8 maneras de renovar tu armario sin comprar nuevas prendas.

- Fashion Revolution Week se celebra del 18 al 24 de abril de 2016, no te olvides de preguntarle a tu marca favoria #quienhizomiropa o #whomademyclothes.