Honest Fashion

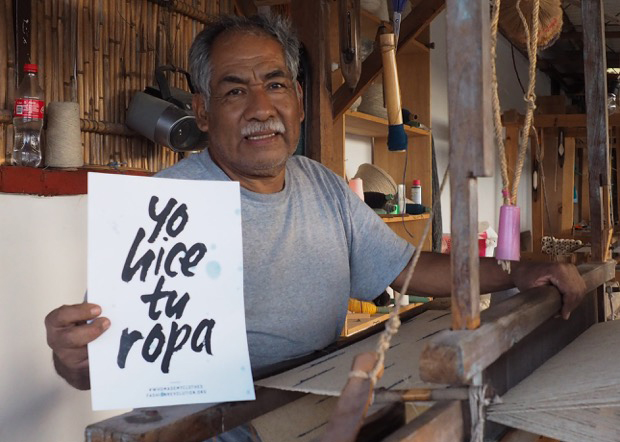

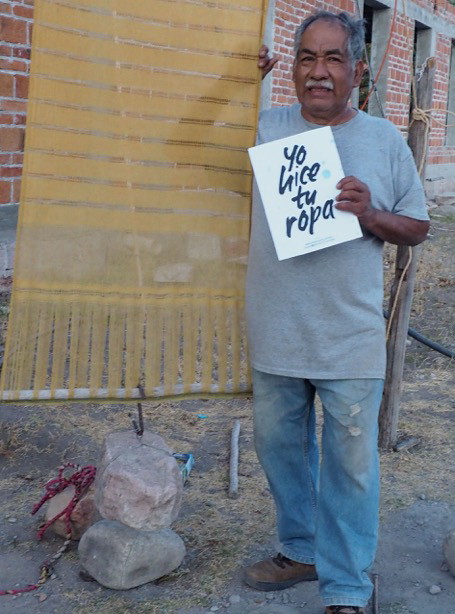

Carry Somers meets Don Arturo Hernandez at the Bia Beguug workshop in Mitla, Oaxaca, Mexico, to investigate the slow process of making a naturally-dyed, hand-woven rebozo shawl.

The earliest textiles in this region were made from the maguey cactus which, contrary to what you might expect, can produce a very delicate, fine fibre for weaving clothing, as well as a strong fibre traditionally used for bags, hammocks and fishing nets in Mesoamerica. At Bia Beguug, their rebozos are made from sheep’s wool and from cotton.

Sheep were introduced to the Oaxaca region by the Spaniards in 1521, along with the two-pedal harness loom. The Zapotec people disliked the Aztecs and so the Spanish friars found a reasonably sympathetic welcome. The Spaniards needed wool garments and horse blankets, and the sarape blankets were exported from these communities all over Mexico.

Don Arturo also uses locally-grown cotton, both the white Mexican criollo cotton which was introduced by the Spaniards, and the indigenous prehispanic coyuchi cotton. Scientists have found cotton fibres dating back 7000 years in caves near Mexico City.

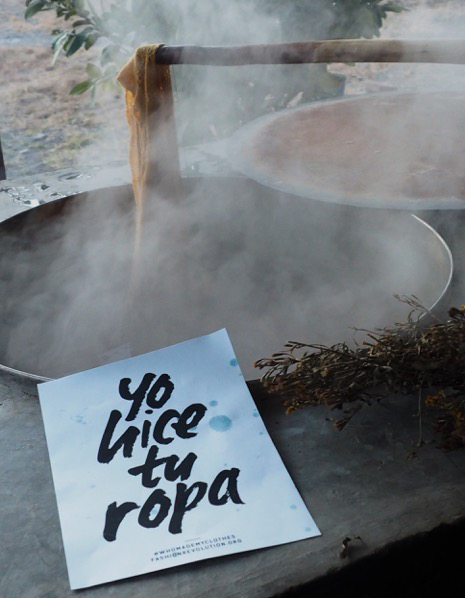

If making a wool rebozo, the sheep’s wool is first spun and wound into skeins before dyeing.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GpaV7th7Rm0

Today, Don Arturo is dyeing with pericone, wild marigold. As well as producing a beautiful golden tone, wild marigold also acts as a natural mordant. Don Arturo will heat the wild marigold for a minimum of twelve hours. He has to keep checking it all day, ensuring it doesn’t boil and adding more kindling, wool and dried cactus leaves, to the fire. Three kilos of dyestuff will dye twelve 2-metre rebozos.

As well as wild marigold, he dyes with añil indigo, cochinilla cochineal, granada pomegranate and pino pine. He will also use nogal walnut, both the shell, which produces a wide range of colours from reds to browns, and also the leaves.

When dyeing other colours, such as cochineal or indigo, a mordant is needed. Don Arturo tells me:

“No hay nada mejor que el orine de niño” (There is nothing better than a boy’s urine for acting as a mordant)

His grandparents used this method and Don Arturo would like to use it, but says that customers don’t want to buy something which has been in contact with human urine, so he now uses Alumbre de potasio, potassium alum, and will also use ceniza or wood ash, left from the fire after heating the dyebath.

The next stage is the weaving. First the warp will be prepared. The warp is the set of longitudinal threads which are kept under tension on the loom.

Weaving is an ancient Zapotec tradition – before the Spaniards introduced the pedal loom and flying shuttle loom, the backstrap loom was widely used throughout Latin America and is still used in many communities today. Alejandro (below), Jesús, Arturo and Felipe are skilled weavers and can weave a rebozo in just two hours.

Once woven, the finished shawl is washed with a natural soap and then left to dry and release any grease for one day.

The final step is to add tassles to the end of the shawl, a job which the women often do at home while looking after their children.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vMwTf3GIBGA

Natural dyes are the antithesis of fast fashion. They produce a surprisingly wide range of colours. We have been using naturally dyed silk on our Panama hat collections at Pachacuti for the past few years and I have been astonished at both the intensity and the subtlety of the colour range.

In her 1972 book The Use of Vegetable Dyes Violetta Thurston says:

No synthetic dye has the lustre, that under-glow of rich colour, that delicious aromatic smell, that soft light and shadow that gives so much pleasure to the eye. These colours are alive.

Although natural dyes, just like analine dyes, have the potential to harm the environment, both in the collection of the dyestuffs from fragile environments and in the environmental consequences of releasing dyes and mordants into water supplies, all of the dyers I met in the Oaxaca region were very conscious of both sustainable harvesting and disposal.

They won’t provide a solution for the toxic chemical devastation caused by the garment industry in many parts of the world – we will need to look to waterless dyes and other future innovations in the dye industry to see the mainstream become more sustainable.

Hand-weaving can be a source of sustainable livelihoods around the world, particularly in rural areas, from India to Mexico. But hand-weaving doesn’t satisfy the demands of an industry requiring perfect thousands of metres of identical woven cloth, or indeed of customers unused to the odd small irregularity in the weave. We take no joy in the character of the cloth from which our clothes are made. We don’t see imperfection as a sign of the hand of the maker, but as a flaw to be eliminated from the production process.

One rebozo takes 3 days to make in total, from the preparation of the dyestuffs to the final shawl. This is fashion which draws on history and heritage. This is fashion with the odd irregularity, both in the dyeing and the weaving, and in my eyes it is all the more beautiful for it.

And maybe things are slowly changing in the fashion world. Faustine Steinmetz, who is quoted as saying that she was ‘keen to rebel against things that were flat’ showed her AW16 collection at The Tate yesterday. The textural qualities of the fabrics only served to enhance their craftsmanship.

Hunger TV said,

By returning to the very beginning, weaving the fabrics by hand rather than sourcing them from somewhere else, every element of the design process is laid bare, allowing us to have a true and raw understanding of the garment. This is wear the true ingenuity of Steinmetz’s work lies in it’s honesty.

I hope this may just be the start of a wider celebration of the honesty, tradition and skill of naturally-dyed and hand-woven fabrics. Let’s celebrate their character. It’s what makes them, and their wearer, unique.

If you are in the Oaxaca region and would like to visit the Bia Beguug workshop, I recommend signing up for Norma Schafer’s natural dye and weaving tour.

To continue to grow Fashion Revolution as a global movement for change, we need your financial support. Even the smallest donation will help us to continue delivering the resources we need to run our revolution. Please donate, be a part of this movement and help us keep going from strength to strength. We can, if you help.