An ethical decision: fast fashion vs. vintage fashion

We all love a dose of vintage. It’s hard not to be enchanted by a piece of clothing with such a huge sense of history attached to it. But have you ever taken the time to research the processes behind how these garments reach your rails? And how exactly does the life-cycle of vintage differ to clothing mass produced within the fast fashion industry? Well, hopefully I can shed some light.

As you may already be aware, the fast fashion industry (referring to fast-turnover high street retailers) generates 100 billion garments per year and is one of the most polluting industries in the world, after oil. This is because retailers restock collections every 4-6 weeks, pressuring us to buy more and think less, leaving a huge amount of unwanted clothing to discarded at landfill (that’s 16 million tonnes a year in the US alone) – the majority of which can actually be recycled. Pretty crazy.

The more environmentally aware shopper may prefer to donate clothing to a charity shop or clothing bank. Here, did you know that your unwanted pair of jeans have just a 1 in 3 chance of finding a lucky new owner in store and a 2 in 3 chance of being sold to textile merchants who either ship them across the world, chop them up into rags or recycle the fibres? Oxfam even has their own “Wastesaver” recycling scheme dedicated to this final process.

A large amount of the reusable clothing finds its way to sub-Saharan African countries where is sold on the second-hand clothing market by local vendors. Whilst this creates jobs in the short term, there are debates as to whether this trade stifles local manufacturing businesses who are unable to compete against the low priced imported garments. Buyers pay an average of just £2.90 for a pair of jeans and £1.50 for a t-shirt.

But what about vintage clothing: What makes it different from second hand? And is buying vintage a decent solution to minimising your carbon footprint and reducing overall resource use?

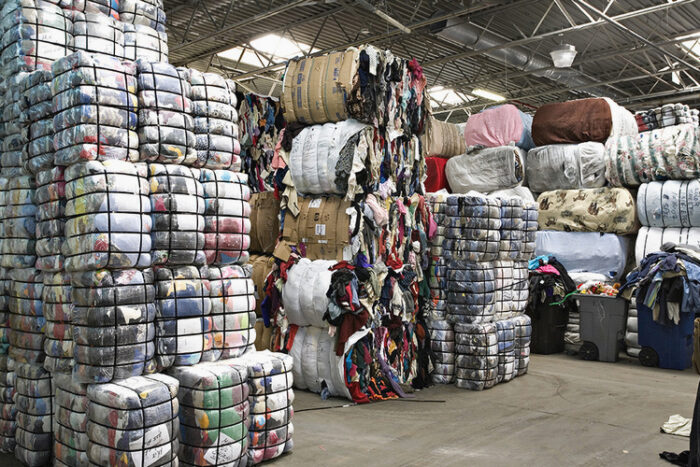

Within the industry, vintage clothing is widely classified as a garment that is 20 years or older (if this item survives beyond 50 years it may proudly call itself an “antique”). The life cycle of a vintage garment will often begin at a recycling clothing bank alongside modern items. Once sorted apart, it is packaged into bales.

These bales are then sold to companies who either sort and sell in-house or act as suppliers to smaller companies who may buy by the kilo or come to “hand-pick” items for their customers.

The clothing will usually be graded A-C and priced accordingly.

Vintage clothing companies are forced to be thrifty with their stock, as unlike major retailers, every unique item arrives in an unpredictable condition and therefore requires a full check before being resold.

Garments are often salvaged, upcycled and sold by various means including:

- Re-working

- Dying

- Washing to remove stains

They are then:

- Steamed

- Photographed

- Measured

Before being listed on E-commerce websites or priced and put out for sale in store.

It’s true – vintage clothing does mirror the world of fast fashion in some ways. Yes, there will still be textile wastage. Some items won’t make it off the rails – but their lifespan is unlikely to be a mere 4 weeks as it so often is on the high street. These garments will be re-entered into the recycling process and sold off in bulk again. They may well be sold to textile merchants who break them down into rags or fibres and sell them on to upholstering companies as stuffing for things like car seats, sofas and punchbags.

The vintage clothing industry will therefore inevitably leave some carbon footprint of its own: transportation being the main resource here. Choosing to ship large pallets of items to and from warehouses by sea freight, as opposed to air, is one way to manage emissions. However, it’s worth remembering that the initial resale of vintage clothing doesn’t usually require any additional materials, other than the odd button or stitch, plus laundering. So in that respect the resource use is still pretty minimal.

Another consideration when buying vintage is the workplace ethics and pay of people employed by sorting factories, as well as the conditions under which the clothes were made in the first place (as difficult as this can be to trace). Look out for labels indicating vintage clothing was made in countries which have tough laws protecting workers rights. Admittedly, it’s a lot easier to locate and challenge your clothing manufacturer in the modern would of fast fashion where garments were produced in the last few years, but you can still have a go at conducting some background research of your own.

One sure fire way to make sure your fashion choices are sustainable is by investing in garments that can stand the test of time. And it’s true: vintage clothing can certainly be of a higher quality, but not by default. There are plenty of 70s polyester blouses circling the rails – but heavy duty fabrics such as denim are an especially durable presence in the industry. Buy carefully.

So, yes, choosing vintage can definitely be a great way to acquire a new wardrobe whilst minimising the resources used. But how about taking a sustainable approach to the garments you already own?

One way to fall back in love with your clothes is to put aside an hour, head over to your wardrobe and experiment with different outfit combinations. When you’re in a rush in the morning you don’t always have the time to look with fresh eyes; frantically clutching for familiar friends, those cherished items you’ve donned a hundred times over, after cautiously eyeing up that dress you love but can never quite figure out how to wear. Learning to layer jumpers and tights with summery pieces can help overcome seasonal boundaries and add a huge dose of versatility to your wardrobe.

You can also have a go at selling your unwanted clothes. Etsy, Depop and eBay can be really fulfilling ventures and bring you a satisfying sense of business achievement. In some ways these platforms facilitate the easy purchase and disposal of garments – but if you’re looking for a long term way to say no to fast fashion then they can help you to clear out and start making the most of what you already have. With selling platforms like these, one of the main resource usages comes down to transportation emissions within the postal distributor sector, which is still significantly less than the production energy that goes into creating a garment from scratch (1 t-shirt uses 2720 litres of water).

It’s also worth noting that in order for vintage clothing to actually continue to exist in the future we must pay attention to what we buy now. Investing in higher quality items or taking the time to repair clothes is a great place to start.

Obviously the least polluting fashion choice would be to never buy any more clothes ever again – new or second hand. No resources would be used: no virgin fibres spun, no transportation used, no oil spent. However we’d then have to consider the prospective loss of jobs if this were to happen; an ethical challenge that is characteristic of dilemmas we face when trying to determine the most constructive approaches towards achieving a sustainable textile industry.

Sustainable living is a test for even the best of us. But it’s not about blaming ourselves or each other. In a society that is constantly pressuring us to purchase with personalised adverts and website cookies tracking our every click, it’s no surprise that the invitation to hop on fast fashion’s runaway train without looking back can be tempting. But awareness is the key. Just taking the time to think about your stance is a constructive step. You’re not expected to have all the answers – but doing a little research of your own, educating yourself and educating others as you do so, is the right way to incite discussion and encourage accountability within the textile industry, both for the supplier and end consumer.

Head to this Fashion Revolution page to learn more about what you can do to get involved in the fashion revolution. Small efforts like tweeting your clothing retailer with the challenge #whomademyclothes could be all it takes to encourage friends, family and strangers to engage in the discussion.

—

Written by Rebecca Linnard of Brag Vintage.