A Moral Sense of Beauty

Moral. It’s not a word we use very often, especially when we talk about fashion. Fashion comes with many adjectives attached: fabulous, iconic, elegant, sumptuous, dashing, nostalgic, effortless… but moral is rarely one of them.

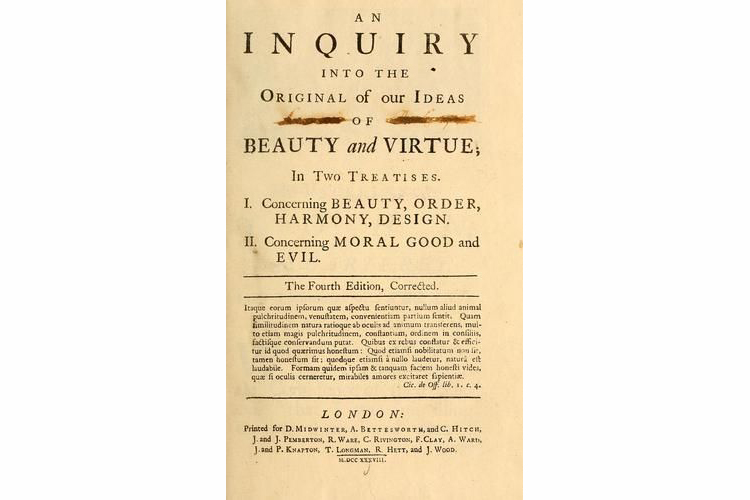

In 1725, Rev Francis Hutcheson wrote An Inquiry into the Original of our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue. In his opinion, an outward perception of beauty was impossible without an inner sense of beauty as well. He called this as a ‘moral sense of beauty’ and, importantly, he understood it as something which could be altered by information and reasoning.

In the mid 18th Century, the first examples of fashion press appeared in Paris with publications like Le Journal de la mode et du Goût. This was the start of the connection between fashion and taste, fashion and ideals, fashion and individualism. It was also the beginning of our moral disengagement as community values gave rise to individual values. The fashionable young women portrayed on its pages embodied the rise of consumer culture.

This desire for new clothes was not confined to 18th century Europe. In Latin America, clothing was recognised as a symbol of social status and prestige and was manipulated by the marginal sectors of society in order to become more socially, economically, politically and culturally reconised.

An overwhelmed husband wrote to the Mercurio Peruano in 1791 setting out the precarious financial situation in which he found himself as a result of his wife’s fashion taste. He protested her need to have a different dress for every social occasion. Whilst his wife had garnered admiration from society in Lima, the husband was unable to pay his debts. For the wife mentioned in the letter, clothing had become a vehicle to make herself visible in a male-dominated society, expressing her status and social freedom.

Our desire for fashion has certainly not diminished in the ensuing 200 years. What has changed, however, is our proximity to, and awareness of, the impact of our purchases.

In the 19th Century, a sweater was an employer or middleman who abused his workers with monotonous work, unhealthy or unsafe conditions and poverty-level wages. The desire of manufacturers to pay the lowest possible wage, coupled with a huge number of rural poor and immigrants looking for work in Britain and the US, produced a climate ripe for the exploitation of workers and the establishment of the first sweatshops. Sweating came to describe work which lacked respect for the human factor. A House of Lords Select Committee on the Sweating System was established in 1889 which publicly exposed the poor conditions in which garment workers toiled. Debate over the morality of production led to unionisation and concerned consumers called for reform. For a while, things got better.

The 20th Century saw waves of trade liberalisation policies starting after World War II, resulting in the offshoring and outsourcing of production to Asia and Latin America. With the relocation of manufacturing came the abrogation of responsibility. It has been endlessly debated whether brands and retailers are morally and legally responsible for their workers overseas.

It has also been questioned whether the fashion consumer in the West is morally responsible for the poor working conditions and unsafe working practices in factories in developing countries. Many of us suspect that the clothes we wear have been made in a sweatshop. Does this affect our moral responsibility? In his book Profits and Principles: Global Capitalism and Human Rights in China, Michael A Santoro argues that ‘consumers are a very big part of the web of moral responsibility for human rights. Ultimately it is consumers who wear the shoes and clothes manufactured in sweatshops… What is needed is a real partnership between companies and consumers, based on a very simple moral compact. Companies must agree to manufacture products in compliance with human rights codes and consumers must agree to place monetary value on such compliance. Both sides of the compact are necessary to safeguard human rights’. In other words, equity for all must become a universal standard and we all bear responsibility for ensuring this happens.

My relative Dyddgu Hamilton (pronounced Dithky) was a close friend of Hilaire Belloc and his wife Elodie. Dyddgu became Belloc’s secretary and subsequently his lifetime correspondent – there are hundreds of letters between them.

I’ve been a voracious Belloc reader for many years – he was a prolific writer with well over 100 published books. I recently came across this quote he wrote in the Sahara, and it struck me that the description of the barbarian could so easily apply to the fast-fashion addict who takes no responsibility and gives no thought to their expanding wardrobe.

‘The Barbarian hopes – and that is the mark of him, that he can have his cake and eat it too. He will consume what civilization has slowly produced after generations of selection and effort, but he will not be at pains to replace such goods, nor indeed has he a comprehension of the virtue that has brought them into being…. We sit by and watch the barbarian…We are tickled by his irreverence ..we laugh. But as we laugh we are watched by large and awful faces from beyond, and on these faces there are no smiles.’

Returning to Frances Hutcheson’s philosophy of beauty, his views are reflected in the worldview of indigenous peoples in the Andes where something which is beautiful is typically something which is well-balanced, something ayni. Everything in the Inca world was based on ayni, a system of exchange based on mutual respect and justice with other communities and cultures throughout their vast empire. Ayni has survived the conquest and capitalism and is still widely practised today. Beauty is about balance, and what is sustainability if not finding a balance between the desires of our generation and the needs of the next?

Before we can rediscover a ‘moral sense of beauty’ on falling in love with a new dress, we need to know that there is equity behind its beauty. To know that there is equity, we need transparency. We cannot hold the many stakeholders in the fashion supply chain to account until we can see them, and we cannot start to tackle exploitation until we can see it. That’s why Fashion Revolution is asking the question #whomademyclothes. We want to know that the clothes we buy are beautiful in every way.